The Flower of the Elite Troops

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

War Weariness' in the Canadian Corps During the Hundred Days Campaign of the First World War

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2013-09-13 Unwilling to Continue, Ordered to Advance: An Examination of the Contributing Factors Toward, and Manifestations of, 'War Weariness' in the Canadian Corps during the Hundred Days Campaign of the First World War Chase, Jordan A.S. Chase, J. A. (2013). Unwilling to Continue, Ordered to Advance: An Examination of the Contributing Factors Toward, and Manifestations of, 'War Weariness' in the Canadian Corps during the Hundred Days Campaign of the First World War (Unpublished master's thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/28595 http://hdl.handle.net/11023/951 master thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY Unwilling to Continue, Ordered to Advance: An Examination of the Contributing Factors Toward, and Manifestations of, ‘War Weariness’ in the Canadian Corps during the Hundred Days Campaign of the First World War by Jordan A.S. Chase A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENT FOR DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY CALGARY, ALBERTA SEPTEMBER, 2013 © Jordan A.S. Chase 2013 Abstract This thesis examines the contributing factors and manifestations of ‘war weariness’ in the Canadian Corps during the final months of the Great War. -

The Waffen-SS in Allied Hands Volume Two

The Waffen-SS in Allied Hands Volume Two The Waffen-SS in Allied Hands Volume Two: Personal Accounts from Hitler’s Elite Soldiers By Terry Goldsworthy The Waffen-SS in Allied Hands Volume Two: Personal Accounts from Hitler’s Elite Soldiers By Terry Goldsworthy This book first published 2018 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2018 by Terry Goldsworthy All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-0858-7 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-0858-3 All photographs courtesy of the US National Archives (NARA), Bundesarchiv and the Imperial War Museum. Cover photo – An SS-Panzergrenadier advances during the Ardennes Offensive, 1944. (German military photo, captured by U.S. military photo no. HD-SN-99-02729; NARA file no. 111-SC-197561). For Mandy, Hayley and Liam. CONTENTS Preface ...................................................................................................... xiii VOLUME ONE Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 The rationale for the study of the Waffen-SS ........................................ 1 Sources of information for this book .................................................... -

USHMM Finding

https://collections.ushmm.org Contact [email protected] for further information about this collection John M. Steiner collection Interviews with former members of the SS, other Nazi officials, and witnesses to Nazi Germany RG-50.593 The following is a draft English-language summary of an interview in German from the John M. Steiner collection. The translation has been not been verified for accuracy, and therefore, may contain errors. Nothing should be quoted or used from this summary without first checking it against the taped interview. Moreover, the description of events in the summary may not match the sequence, time-code, or track number of the audio files. Interview with Harald von Saucken Recorded in 1976 Speaker says that he will discuss his autobiography, with emphasis on his membership in the Waffen SS from 1934 to 1947. He talks about touring Dachau in November 1942. He discusses his years as an American POW and his post-war career managing American businesses in Germany. Says that he was born on April 23, 1915 in Heidelberg; that his parents divorced in 1921/2 and he spent his youth, either in boarding schools or with his mother. He lived in the Munich area, completed Gymnasium in Mainz in 1934, and then returned to his village, Oberallmanshausen on the Starnberger See. He wanted to continue his studies but had insufficient funds so he decided to join the military. He was deferred due to treaty limitations on the size of the Reichswehr and was very disappointed; however a neighbor told him that there was another avenue – the SS had a branch called the SS-Verfügungstruppe (SS-VT -SS Dispositional Troops). -

The American Expeditionary Forces in World War I: the Rock of the Marne. Stephen L

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 5-2008 The American Expeditionary Forces in World War I: The Rock of the Marne. Stephen L. Coode East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the Military History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Coode, Stephen L., "The American Expeditionary Forces in World War I: The Rock of the Marne." (2008). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 1908. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/1908 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The American Expeditionary Forces in World War I: The Rock of the Marne _________________________ A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of History East Tennessee State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in History _________________________ by Stephen Coode May 2008 _________________________ Committee Chair: Dr. Stephen Fritz Committee Member: Dr. Ronnie Day Committee Member: Dr. Colin Baxter Keywords: World War 1914-1918, American Expeditionary Forces, U.S. Third Infantry Division, Second Battle of The Marne ABSTRACT The American Expeditionary Forces in World War I: The Rock of the Marne by Stephen Coode American participation in the First World War developed slowly throughout 1917 to a mighty torrent during the last six months of the war. -

1. Introduction 1 Preface 1

A European Anabasis: Introduction 11/17/03 4:39 PM 1. Introduction 1 Preface 1. Introduction The Volunteer Phenomenon Volunteer Phenomenon The participation of foreign nationals in the service of the German armed forces during the SS Recruiting Second World War has evoked both curiosity and consternation. Many Germans saw their Ideology & Race presence as evidence of the legitimacy of the war against Bolshevik Russia and proof of a New Order Russo-German reassuring measure of acceptance of the "New Order in Europe," the political structure the War German Reich's envisioned in occupied Europe. For the resistance movements and post-war 2. Propaganda liberated governments, these volunteers represented collaboration and treason of the 3. Neutral Variation basest order. 4. Transformation 5. Fanaticism What foreign nationals volunteered for service in the German forces? For what ends did 6. Collaboration they serve and why? How many served, and to what extent did they contribute to German Bibliography Maps military fortunes? This study attempts to analyze the experience of Western European volunteers in the German Army and Waffen-SS in order to discuss the character of their military collaboration, their motivations, and the effects of their service on the German war effort. In so doing, it will focus on German efforts to integrate non-German nationals into the German Wehrmacht (armed forces), how successful they were in doing so, and what measures they took to achieve their objectives. Although foreign nationals from virtually every European nation served in one or more branches of the German armed forces, those serving in the ground forces far outnumbered those who served in the air and at sea; they also took a more direct part in combat than the others. -

Proquest Dissertations

BUTCHER AND BOLT: CANADIAN TRENCH RAIDING DURING THE GREAT WAR, 1915-1918 by Colin David Garnett, B.A. (Hons.) A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario ©2011 Colin David Garnett Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 OttawaONK1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-81651-6 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-81651-6 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Hungarian Rhapsody Personalities Compiled by Chip Saltsman

Hungarian Rhapsody Personalities Compiled by Chip Saltsman The battles in Hungary during late 1944 and early 1945 featured an interesting cast of characters, some for their infamy and some for the mark they would make on the world stage in the years after the war. Leonid Brezhnev (December 19, 1906 - November 10, 1982) – Major General Leonid Brezhnev (center figure in the photo), is the future leader of the Soviet Union from 1964 until his death in 1982. Helped in his rise by political patron Nikita Khrushchev, Brezhnev was the Political Officer of the 18th Army in the Caucasus, particularly supporting their landings at Novorossiysk (about which he wrote a book named “The Little Land”). During the Hungarian Rhapsody Campaign, Brezhnev was the Chief of the Political Directorate of the 4th Ukrainian Front (the white frame units in the northern part of the map). Oskar Dirlewanger (26 September 1895 – 7 June 1945) was arguably the evilest man in the Nazi SS. Dirlewanger served in France during World War I, was wounded 6 times, and apparently emerged shattered by the frenzied violence and barbarism of years in the trenches. This, combined with an amoral personality, alcoholism, and sadistic sexual orientation, determined his path to “terror warfare” in the Second World War. He was a member of the Freikorps and active with the SA between the wars, embezzling money from his employers which he funneled to the SA. He fought in the Spanish Civil War as a member of the Condor Legion, and was wounded three more times. At the start of World War 2, he joined the Waffen SS with the rank of Obersturmführer (first lieutenant), and eventually became the commander of the so-called Dirlewanger Brigade. -

Strategic Utility of the Russian Spetsnaz

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Calhoun, Institutional Archive of the Naval Postgraduate School Calhoun: The NPS Institutional Archive Theses and Dissertations Thesis and Dissertation Collection 2016-12 Strategic utility of the Russian Spetsnaz Atay, Abdullah Monterey, California: Naval Postgraduate School http://hdl.handle.net/10945/51562 NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL MONTEREY, CALIFORNIA THESIS STRATEGIC UTILITY OF THE RUSSIAN SPETSNAZ by Abdullah Atay December 2016 Thesis Advisor: Hy Rothstein Second Reader: Douglas A. Borer Approved for public release. Distribution is unlimited. THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Form Approved OMB No. 0704-0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instruction, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302, and to the Office of Management and Budget, Paperwork Reduction Project (0704-0188) Washington DC 20503. 1. AGENCY USE ONLY 2. REPORT DATE 3. REPORT TYPE AND DATES COVERED (Leave blank) December 2016 Master’s thesis 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5. FUNDING NUMBERS STRATEGIC UTILITY OF THE RUSSIAN SPETSNAZ 6. AUTHOR(S) Abdullah Atay 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 8. PERFORMING Naval Postgraduate School ORGANIZATION REPORT Monterey, CA 93943-5000 NUMBER 9. -

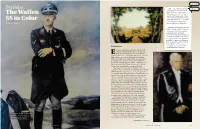

The Waffen SS in Color

Buy Now! Portfolio: left — Nazi Evening Ceremony, Home King’s Plaza, 15 October 1933 in Munich. The occasion was the The Waffen “Day of German Art,” so desig- nated for the laying of the corner- stone of the museum, The House SS in Color of German Art. Black-coated men of the Allgemeine (General) SS By Blaine Taylor line the walkway on both sides. below — Government President Gareis, 1940 by artist M. Henseler, wearing the rank of SS brigadier general in silver on a black tuxedo dinner jacket with white tie ensemble. The silver cord worn on the right shoulder is an adjutant’s aiguillette common to all armies, both then and now. This uniform was only worn on formal occa- Introduction sions, such as receptions at the Reich Chancellery in Berlin. ven now, almost seven decades after the end of the Second World War, interest in what was E undoubtedly the Third Reich’s most infamous armed forces branch—the Waffen (Armed) SS—remains high, with no expectation of that interest declining in the foreseeable future. Indeed, it’s a fair statement the infamy of the SS puts it on an equal footing—in terms of noteriety in popular culture—with the Roman Praetorian Guard, the Turkish Janissaries, the French Foreign Legion and Napoleon’s Imperial Guard. That noteriety is even more remarkable when we consider the term “Waffen SS” was itself largely unknown at World War II’s outset. Even so, the organization then soon made a name for itself for ferocity and brutality on and off the battlefi eld. -

US Intelligence and the Subversion of Media in Post-War Germany

Volume 2 Issue 4 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF HUMANITIES AND March 2016 CULTURAL STUDIES ISSN 2356-5926 Project KMMANLY: U.S. Intelligence and the Subversion of Media in Post-War Germany Badis Ben Redjeb University of Tunis, Tunisia [email protected] Abstract This research explores the manner in which the Central Intelligence Agency orchestrated a black operation in West Germany in the early Cold War to enhance the national interests of the United States. At a time when the latter was openly condemning German military tradition, branches of United States intelligence were organizing a covert nationwide media campaign targeting pacifists and neutralists and all those opposed to the remilitarization of West Germany and its integration into a European military pact of defense. This article analyses how, through clandestine assets, the Central Intelligence Agency spent thousands of U.S. dollars to convince the German population of the necessity to rearm. Keywords: West Germany, Central Intelligence Agency, KMMANLY, remilitarization. http://www.ijhcs.com/index.php/ijhcs/index Page 384 Volume 2 Issue 4 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF HUMANITIES AND March 2016 CULTURAL STUDIES ISSN 2356-5926 Introduction The start of the Cold War in 1947 and the creation of two antagonistic blocs dramatically altered world affairs, triggering new scopes and issues in the field of international relations.1 The Berlin Crisis of 1948-1949 and the beginning of the Korean War in 1950 made the United States realize that an open conflict with the Soviet Union could start at any time and that, in order to gain momentum, the geostrategic balance in Europe had to be adjusted. -

Eine „Vergangenheit, Die Nicht Vergehen Will“

Kapitel 7 Eine „Vergangenheit, die nicht vergehen will“ Der Tod des „Führers“ Adolf Hitler bedeutete das unwiderrufliche Ende der Attraktion des bewaffneten Arms der SS. Zwischen 400.000 und 500.000 dieser Männer hatten den Weltkrieg überlebt. Die Mehrheit assimilierte und integrierte sich so geräuschlos, dass von diesem Anpassungsprozess kaum Papierspuren zeugen. Die von den Alliierten zunächst befürchtete Bildung einer „fünfte Kolonne“ blieb aus. Die Angehörigen der Waffen-SS, die aus dem Zweiten Weltkrieg zurück- kehrten, verstanden sich mehrheitlich nicht als Teil der Allgemeinen SS, sondern machten geltend, als „vierter Wehrmachtsteil“ neben Heer, Luft- waffe und Marine für Deutschland gedient zu haben. Seit Anfang der 1950er Jahre fand sich unter dem Namen „Hilfsgemeinschaft auf Gegenseitigkeit für Soldaten der Waffen-SS“ (HIAG) eine beachtliche Minderheit ehemaliger An- gehöriger zusammen.1 Trotz ihres Anspruchs repräsentierte die HIAG keines- wegs die ganze ehemalige Waffen-SS und zählte in den späten 1950er Jahren kaum mehr als 20.000 Ehemalige in ihren Reihen.2 An ihrer Spitze standen ehemalige Generale der Waffen-SS wie Felix Steiner und Paul Hausser,3 die sich öffentlich wortgewaltig für ihre Schützlinge einsetzten. Die HIAG ver- blieb in einer Grauzone: Sie beharrte fortwährend auf ihrer Rolle als Sozial- und Rechtsinstitution für die Männer der Waffen-SS, während sich ihre Angehörigen immer wieder mit ihrer Zugehörigkeit zu Hitlers Vorzeigetruppe brüsteten. So legitim ihr Ansinnen sein mochte, mit demokratischen Mitteln für eine rechtliche und soziale Anerkennung der Waffen-SS als eine der Wehr- macht gleichartigen Kampftruppe zu werben, ließ die Zusammensetzung ihrer Führungsgremien doch erkennen, dass die HIAG auch eine politische Agenda hatte. -

Children at War P.W

Caution: Children at War P.W. Singer Parameters Winter 2001-2002 After less than two weeks of training, the strike force of 150 British paratroopers deployed to the target zone, a ramshackle camp located in the jungles of Sierra Leone. At H-Hour, the assault group raced out from three RAF Chinook CH-47s, while three other helicopters laid down curtains of covering fire. At the same time, Special Air Service (SAS) snipers, who had waited for nearly a week in the surrounding swamps, opened up. Much of the force had to wade through chest-deep water and then hack through 150 meters of jungle while under fire, but they persevered to the objective: a collection of low huts where six hostages were held. The hostages were hurried into waiting choppers and the operation was quickly over. The fighting had been brief but "brutal."[1] Estimates of enemy dead ranged from 25 to 150. This British rescue assault, code-named Operation Barras, took place in September 2000, but received little attention in the United States. It merits mention not because it was a textbook operation lasting just 20 minutes, but rather because of the nature of the enemy: the "West Side Boys," a rogue militia primarily made up of children. In fact, the very reason for Operation Barras was that 16 days earlier, the "Boys" had seized a patrol from the British Royal Irish Regiment, deployed on military training duties. The soldiers had been surrounded and then captured when their squad commander was unwilling to fire on "children armed with AKs."[2] Operation Barras was one of the first Western engagements with this new, troubling feature of global violence.