Children at War P.W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

War Weariness' in the Canadian Corps During the Hundred Days Campaign of the First World War

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2013-09-13 Unwilling to Continue, Ordered to Advance: An Examination of the Contributing Factors Toward, and Manifestations of, 'War Weariness' in the Canadian Corps during the Hundred Days Campaign of the First World War Chase, Jordan A.S. Chase, J. A. (2013). Unwilling to Continue, Ordered to Advance: An Examination of the Contributing Factors Toward, and Manifestations of, 'War Weariness' in the Canadian Corps during the Hundred Days Campaign of the First World War (Unpublished master's thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/28595 http://hdl.handle.net/11023/951 master thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY Unwilling to Continue, Ordered to Advance: An Examination of the Contributing Factors Toward, and Manifestations of, ‘War Weariness’ in the Canadian Corps during the Hundred Days Campaign of the First World War by Jordan A.S. Chase A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENT FOR DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY CALGARY, ALBERTA SEPTEMBER, 2013 © Jordan A.S. Chase 2013 Abstract This thesis examines the contributing factors and manifestations of ‘war weariness’ in the Canadian Corps during the final months of the Great War. -

The American Expeditionary Forces in World War I: the Rock of the Marne. Stephen L

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 5-2008 The American Expeditionary Forces in World War I: The Rock of the Marne. Stephen L. Coode East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the Military History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Coode, Stephen L., "The American Expeditionary Forces in World War I: The Rock of the Marne." (2008). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 1908. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/1908 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The American Expeditionary Forces in World War I: The Rock of the Marne _________________________ A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of History East Tennessee State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in History _________________________ by Stephen Coode May 2008 _________________________ Committee Chair: Dr. Stephen Fritz Committee Member: Dr. Ronnie Day Committee Member: Dr. Colin Baxter Keywords: World War 1914-1918, American Expeditionary Forces, U.S. Third Infantry Division, Second Battle of The Marne ABSTRACT The American Expeditionary Forces in World War I: The Rock of the Marne by Stephen Coode American participation in the First World War developed slowly throughout 1917 to a mighty torrent during the last six months of the war. -

Proquest Dissertations

BUTCHER AND BOLT: CANADIAN TRENCH RAIDING DURING THE GREAT WAR, 1915-1918 by Colin David Garnett, B.A. (Hons.) A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario ©2011 Colin David Garnett Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 OttawaONK1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-81651-6 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-81651-6 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Strategic Utility of the Russian Spetsnaz

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Calhoun, Institutional Archive of the Naval Postgraduate School Calhoun: The NPS Institutional Archive Theses and Dissertations Thesis and Dissertation Collection 2016-12 Strategic utility of the Russian Spetsnaz Atay, Abdullah Monterey, California: Naval Postgraduate School http://hdl.handle.net/10945/51562 NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL MONTEREY, CALIFORNIA THESIS STRATEGIC UTILITY OF THE RUSSIAN SPETSNAZ by Abdullah Atay December 2016 Thesis Advisor: Hy Rothstein Second Reader: Douglas A. Borer Approved for public release. Distribution is unlimited. THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Form Approved OMB No. 0704-0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instruction, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302, and to the Office of Management and Budget, Paperwork Reduction Project (0704-0188) Washington DC 20503. 1. AGENCY USE ONLY 2. REPORT DATE 3. REPORT TYPE AND DATES COVERED (Leave blank) December 2016 Master’s thesis 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5. FUNDING NUMBERS STRATEGIC UTILITY OF THE RUSSIAN SPETSNAZ 6. AUTHOR(S) Abdullah Atay 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 8. PERFORMING Naval Postgraduate School ORGANIZATION REPORT Monterey, CA 93943-5000 NUMBER 9. -

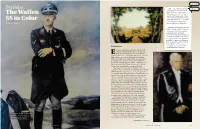

The Waffen SS in Color

Buy Now! Portfolio: left — Nazi Evening Ceremony, Home King’s Plaza, 15 October 1933 in Munich. The occasion was the The Waffen “Day of German Art,” so desig- nated for the laying of the corner- stone of the museum, The House SS in Color of German Art. Black-coated men of the Allgemeine (General) SS By Blaine Taylor line the walkway on both sides. below — Government President Gareis, 1940 by artist M. Henseler, wearing the rank of SS brigadier general in silver on a black tuxedo dinner jacket with white tie ensemble. The silver cord worn on the right shoulder is an adjutant’s aiguillette common to all armies, both then and now. This uniform was only worn on formal occa- Introduction sions, such as receptions at the Reich Chancellery in Berlin. ven now, almost seven decades after the end of the Second World War, interest in what was E undoubtedly the Third Reich’s most infamous armed forces branch—the Waffen (Armed) SS—remains high, with no expectation of that interest declining in the foreseeable future. Indeed, it’s a fair statement the infamy of the SS puts it on an equal footing—in terms of noteriety in popular culture—with the Roman Praetorian Guard, the Turkish Janissaries, the French Foreign Legion and Napoleon’s Imperial Guard. That noteriety is even more remarkable when we consider the term “Waffen SS” was itself largely unknown at World War II’s outset. Even so, the organization then soon made a name for itself for ferocity and brutality on and off the battlefi eld. -

Third-Generation Warfare and the War in the Trenches

THIRD-GENERATION WARFARE AND THE WAR IN THE TRENCHES Maj Jay Tarzwell JCSP 43 DL PCEMI 43 AD Exercise Solo Flight Exercice Solo Flight Disclaimer Avertissement Opinions expressed remain those of the author and Les opinons exprimées n’engagent que leurs auteurs do not represent Department of National Defence or et ne reflètent aucunement des politiques du Canadian Forces policy. This paper may not be used Ministère de la Défense nationale ou des Forces without written permission. canadiennes. Ce papier ne peut être reproduit sans autorisation écrite. © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, as © Sa Majesté la Reine du Chef du Canada, représentée par represented by the Minister of National Defence, 2018. le ministre de la Défense nationale, 2018. CANADIAN FORCES COLLEGE – COLLÈGE DES FORCES CANADIENNES JCSP 43 DL – PCEMI 43 AD 2017 – 2018 EXERCISE SOLO FLIGHT – EXERCICE SOLO FLIGHT THIRD-GENERATION WARFARE AND THE WAR IN THE TRENCHES Maj Jay Tarzwell “This paper was written by a student “La présente étude a été rédigée par un attending the Canadian Forces College stagiaire du Collège des Forces in fulfilment of one of the requirements canadiennes pour satisfaire à l'une des of the Course of Studies. The paper is a exigences du cours. L'étude est un scholastic document, and thus contains document qui se rapporte au cours et facts and opinions, which the author contient donc des faits et des opinions alone considered appropriate and que seul l'auteur considère appropriés et correct for the subject. It does not convenables au sujet. Elle ne reflète pas necessarily reflect the policy or the nécessairement la politique ou l'opinion opinion of any agency, including the d'un organisme quelconque, y compris le Government of Canada and the gouvernement du Canada et le ministère Canadian Department of National de la Défense nationale du Canada. -

The Revolution in Military Affairs and Its Interpreters: Implications for National and International Security Policy

WARNING! The views expressed in FMSO publications and reports are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official policy or position of the Department of the Army, Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government. The Revolution in Military Affairs and its Interpreters: Implications for National and International Security Policy Dr. Jacob W. Kipp Foreign Military Studies Office, Fort Leavenworth, KS. Paper presented at: FMSO - Academy of State Management of President of the Russian Federation September 1995 Moscow, Russia INTRODUCTION The Gulf War initiated an intense debate in the United States and elsewhere over the existence of a "revolution in military affairs" [RMA]. Since the end of the Cold War the RMA's significance for U. S. Defense planning has become a part of the ongoing conflict over military downsizing, funding current operations, and maintaining the technological initiative for U. S. into the next century. The exchanges have become increasingly intense. The two positions, pitting advocates against doubting Thomas's, contrast a revolutionary interpretation as opposed to an evolutionary one. In the former case, the Gulf War represents the harbinger of radical changes, transforming warfare as profoundly as mechanization and the introduction of nuclear weapons.1 This interpretation sees the RMA as the transformation of combat through the appearance of advanced, high-accuracy, precision strike weapons, advanced systems of C3I, electronic warfare and computer simulation. Quality forces will be those equipped, organized, and trained to make use of advantages in information, penetration, and precision against an opposing force. Describing the operational environment of land warfare in the 21st century, General Gordon Sullivan, then Chief of Staff of the US Army, and his coauthor, LTC James M. -

The Battle of Beersheba

Running head: BATTLE OF BEERSHEBA The Battle of Beersheba Strategic and Tactical Pivot of Palestine Zachary Grafman A Senior Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation in the Honors Program Liberty University Spring 2013 BATTLE OF BEERSHEBA 2 Acceptance of Senior Honors Thesis This Senior Honors Thesis is accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation from the Honors Program of Liberty University. ______________________________ David Snead, Ph.D. Thesis Chair ______________________________ Robert Ritchie, M.A. Committee Member ______________________________ Randal Price, Ph.D. Committee Member ______________________________ Brenda Ayres, Ph.D. Honors Director ______________________________ Date BATTLE OF BEERSHEBA 3 Abstract The Battle of Beersheba, fought on October 31, 1917, was a vital turning point in the British campaign against the Ottoman Turks. The battle opened a gap in the Turkish line that eventually resulted in the British takeover of Palestine. The British command saw the cavalry charge of the 4th Light Horse Brigade as a new tactical opportunity, and this fac- tored into the initiative for new light tank forces designed around the concepts of mobility and flanking movements. What these commanders failed to realize was that the Palestine Campaign was an anachronistic theater of war in comparison to the rest of the Great War. The charge of the 4th Light Horse, while courageous and vital to the success of the Battle of Beersheba, also owed its success to a confluence of advantageous circumstances, which the British command failed to take into account when designing their light tank forces prior to World War II. BATTLE OF BEERSHEBA 4 The Battle of Beersheba: Strategic and Tactical Pivot of Palestine World War I has taken its place in the public perception as a trench war, a conflict of brutal struggle between industrial powers that heaped up dead and wounded and for- ever changed Europe’s consciousness. -

Spetsnaz: Russias Special Forces Pdf Free Download

SPETSNAZ: RUSSIAS SPECIAL FORCES PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Mark Galeotti,Johnny Shumate | 64 pages | 23 Jun 2015 | Bloomsbury Publishing PLC | 9781472807229 | English | Oxford, United Kingdom Alpha Group - Wikipedia Kettlebell circuit. Turkish Get Ups 5 each side. Complete X3 rounds of each before progressing. Kettlebell Cossack squats. X10 reps on each side. Hand-to-hand combat — 3 minutes all-out rounds on the heavy bag. X3 rounds before progressing. Strength test see below. Backpack running. Chin up. Weighted crunches. Kettlebell Windmills. Kettlebell drag. Turkish get up. Kettlebell Swing. Kettlebell Clean. Kettlebell Cossack Squat. Backpack run. Heavy bag training. Endurance test. Mountain climbers. Jumping Lunges. Switch feet every jump. Strength test. Pull-ups with an overhand grip. Squat jumps , the same as in the first test. The chest must touch the ground, the body must stay straight. Touch your left knee with your right elbow, on the next rep touch your right knee with your left elbow. Keep alternating. Do as many reps as possible in 2 minutes. Burpees maximum reps in 2 minutes. Pull up. Circuit Two. Chin-ups underhand grip X12 repetitions X3 rounds. Core session — KB Half get-ups X10 reps each side. KB planks with alternate shoulder taps X1 minute. Russian twists with KB. Reps X4 rounds. KB Thrusters X15 reps. X25 reps one-armed kettlebell swings. X3 rounds. Kettlebell walks. Have one KB pressed overhead and carry one KB by side. Walk 25yds. Change sides and return. X 3 rounds. Half Get-ups. Planks with a kettlebell. Russian Twists. Kettlebell swings. Kettlebell Snatch. Racked Kettlebell Walks. Overhead Kettlebell walks. -

The Germans and Vimy Ridge, April 1917

Canadian Military History Volume 25 Issue 2 Article 16 2016 “The Battle-Fortune of Marshal Hindenburg is not Bound up with the Possession of a Hill”: The Germans and Vimy Ridge, April 1917 Holger Herwig Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.wlu.ca/cmh Part of the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Herwig, Holger "“The Battle-Fortune of Marshal Hindenburg is not Bound up with the Possession of a Hill”: The Germans and Vimy Ridge, April 1917." Canadian Military History 25, 2 (2016) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in Canadian Military History by an authorized editor of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Herwig: “The Battle-Fortune of Marshal Hindenburg" “The Battle-Fortune of Marshal Hindenburg is not Bound up with the Possession of a Hill” The Germans and Vimy Ridge, April 1917 HOLGER HERWIG Abstract : On 9 April 1917 four Canadian divisions and one British division of 170,000 men broke through the “Vimy Group” of German Sixth Army of some 40,000 men. By late afternoon, the Germans had been driven off the Ridge. That day, as Brigadier-General Alexander Ross famously put it, constituted “the birth of a nation.” Rivers on ink have been spilled in the Canadians’ actions that day, but little attention has been paid to “the other side of the hill.” Which German units defended the Ridge? What was the quality of their leadership? Why did the defence collapse so quickly? Why did the German soldiers not break and run? And how were they able to prevent a deeper British-Canadian breakthrough? On the basis of German sources, this article seeks to provide answers to those questions. -

The Recruitment of Colonial Troops in Africa and Asia and Their Deployment in Europe During the First World War Christian Koller*

Immigrants & Minorities Vol. 26, Nos. 1/2, March/July 2008, pp. 111–133 The Recruitment of Colonial Troops in Africa and Asia and their Deployment in Europe during the First World War Christian Koller* School of History, Welsh History and Archaeology, Bangor University The impact of the First World War on the colonies was profound and many-sided.1 A conflict that began in the Balkans turned into a general European war in July and August 1914, and then took on extra-European dimensions, particularly as some of the belligerent states ranked as the most important colonial powers globally. After the outbreak of the war, there was immediate fighting in several parts of the world as Great Britain, France, Belgium and Japan as well as the British dominions Australia, New Zealand and South Africa attacked the German colonies in Africa, Asia and the Pacific. Most of these territories were conquered by the Entente powers within a short time. Already in October and November 1914, Japanese troops occupied the German islands in Micronesia and captured the city of Tsingtau, where about 5000 Germans were made prisoners of war. Between August and November 1914 troops from Australia and New Zealand conquered Samoa, New Guinea and the Bismarck Archipelago, all of them German possessions.2 The German colonies in Africa were defended by so-called ‘Schutztruppen’, made up of German officers and African soldiers. While British and French troops overwhelmed Togo in August 1914, the fighting in Cameroon lasted until January 1916.3 German South West Africa was attacked by South Africa on behalf of the Entente powers. -

The Future of the Russian Military Russia’S Ground Combat Capabilities and Implications for U.S.-Russia Competition Appendixes

ARROYO CENTER The Future of the Russian Military Russia’s Ground Combat Capabilities and Implications for U.S.-Russia Competition Appendixes Andrew Radin, Lynn E. Davis, Edward Geist, Eugeniu Han, Dara Massicot, Matthew Povlock, Clint Reach, Scott Boston, Samuel Charap, William Mackenzie, Katya Migacheva, Trevor Johnston, Austin Long Prepared for the United States Army Approved for public release; distribution unlimited For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/RR3099 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © Copyright 2019 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org Preface This document presents the results of a project titled U.S.-Russia Long Term Competition, spon- sored by the Deputy Chief of Staff, G-3/5/7, U.S.