Case Study Follow-Up Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Technology Guide for Arts & Culture

NPower’s TECHNOLOGY GUIDE for Nonprofit Leaders A mission support tool for UNDERWRITTEN BY NPOWER’S TECHNOLOGY GUIDE – ARTS AND CULTURE | 1 Contents Welcome 3 Defining the Arts and Culture Sector 5 Impact of Arts and Culture 7 Changes facing the Arts 8 Challenges 9 Opportunities 13 Tools to help you meet your goals 18 Technology solution close-up 20 Conclusion 33 Resources and additional information 34 Acknowledgements 38 NPower is a federation of independent, locally-based nonprofits providing accessible technology help that strengthens the work of other nonprofits. NPower’s mission is to ensure all nonprofits can use technology to expand the reach and impact of their services. We envision a thriving nonprofit sector in which all organizations have access to the best technology resources and know-how, and can apply these tools in pursuit of healthy, vibrant communities. For more information, visit our website at www.NPower.org. UNDERWRITTEN BY THE SBC FOUNDATION 2 | NPOWER’S TECHNOLOGY GUIDE – ARTS AND CULTURE Welcome to... NPower’s “Nonprofit Leader’s Technology Guide: A Mission Support Tool for Arts and Culture.” This is one of four “Technology for Leaders” guides published by NPower, a national organization devoted to bringing free or low-cost technology help to nonprofits, and funded by a grant from the SBC Foundation, the philanthropic arm of SBC Communications Inc. These papers highlight technology innovation in four nonprofit sectors: arts and culture, health and human services, education, and community development. The goal is to inspire nonprofits about the possibilities of technology as a service delivery tool, and to provide nonprofit leaders with real-world examples that demonstrate that potential. -

The Creation of a Gift Shop at Great Lakes Theater Festival

THE CREATION OF A GIFT SHOP AT THE GREAT LAKES THEATER FESTIVAL A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of The University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Mary Chamberlain December, 2011 THE CREATION OF A GIFT SHOP AT THE GREAT LAKES THEATER FESTIVAL Mary Chamberlain Thesis Approved: Accepted: _________________________________ _________________________________ Durand L. Pope Neil Sapienza Advisor School Director _________________________________ _________________________________ Robert Taylor Chand Midha, Ph.D. Committee Member Dean of College of Fine and Applied Arts _________________________________ _________________________________ Neil B. Sapienza George R. Newkome, Ph.D. Committee Member Dean of the Graduate School _________________________________ Date ii TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER Page I. BRIEF HISTORY OF GREAT LAKES THEATER FESTIVAL……………………..1 GLTF’s New Home at the Hanna Theatre………………………………………...4 II. RESEARCHING, SELECTING AND INTERVIEWING THEATRE COMPANIES..6 Theatre Profiles……………………………………………………………………8 GLTF Staff Involvement…………………………………………………………10 III. EVALUATING RESULTS……………………………………………………….…11 Design and Layout……………………………………………………………….11 Operations..………………………………………………………………………11 Marketing…………………………………………………………………..…….12 Inventory…………………………………………………………………………12 Vendors…………………………………………………………………………..13 Budget……………………………………………………………………………14 IV. ESTABLISHING THE GIFT SHOP………………………………………………...15 Recommendations…………………………………………………………..……15 Unrelated Income & Mission-Related Branding…………………………….......16 -

Arts and Culture Anchors Cover

Arts and Culture Institutions as Urban Anchors Livingston Case Studies in Urban Development August 2014 Arts and Culture Anchor Institutions as Urban Anchors Livingston Case Studies in Urban Development Penn Institute for Urban Research University of Pennsylvania Philadelphia, PA Eugénie L. Birch, Cara Griffin, Amanda Johnson, Jonathon Stover Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................. 1 Case 1. The Adrienne Arsht Center for the Performing Arts, Miami, Florida: Creating a New Institution ........................................................................................... 5 Case 2. Arena Stage, Washington, D.C.: Developing The Mead Center .................. 25 Case 3. The Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois: Attracting Civic Support ...... 41 Case 4: The High Museum of Art, Atlanta, Georgia: Expanding the Museum ......... 55 Case 5: The Kimmel Center: Facing Challenges ...................................................... 65 Case 6: The Martin Luther King, Jr. Library, San Jose, California: Developing a Joint Library ............................................................................................................... 87 Case 7: The Music Center: Taking on New Roles .................................................. 109 Case 8: The Woodruff Arts Center, Atlanta, Georgia: Adapting to a Changing City ................................................................................... 125 Introduction Urban Anchors Additionally, -

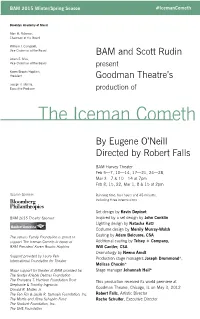

The Iceman Cometh

BAM 2015 Winter/Spring Season #IcemanCometh Brooklyn Academy of Music Alan H. Fishman, Chairman of the Board William I. Campbell, Vice Chairman of the Board BAM and Scott Rudin Adam E. Max, Vice Chairman of the Board present Karen Brooks Hopkins, President Goodman Theatre’s Joseph V. Melillo, Executive Producer production of The Iceman Cometh By Eugene O’Neill Directed by Robert Falls BAM Harvey Theater Feb 5—7, 10—14, 17—21, 24—28, Mar 3—7 & 10—14 at 7pm Feb 8, 15, 22, Mar 1, 8 & 15 at 2pm Season Sponsor: Running time: four hours and 45 minutes, including three intermissions Set design by Kevin Depinet BAM 2015 Theater Sponsor Inspired by a set design by John Conklin Lighting design by Natasha Katz Costume design by Merrily Murray-Walsh The Jaharis Family Foundation is proud to Casting by Adam Belcuore, CSA support The Iceman Cometh in honor of Additional casting by Telsey + Company, BAM President Karen Brooks Hopkins Will Cantler, CSA Dramaturgy by Neena Arndt Support provided by Laura Pels Production stage managers Joseph Drummond*, International Foundation for Theater Melissa Chacón* Major support for theater at BAM provided by: Stage manager Johannah Hail* The Gladys Krieble Delmas Foundation The Francena T. Harrison Foundation Trust This production received its world premiere at Stephanie & Timothy Ingrassia Donald R. Mullen Jr. Goodman Theatre, Chicago, IL on May 3, 2012 The Fan Fox & Leslie R. Samuels Foundation, Inc. Robert Falls, Artistic Director The Morris and Alma Schapiro Fund Roche Schulfer, Executive Director The Shubert Foundation, Inc. The SHS Foundation Who’s Who Patrick Andrews Kate Arrington Brian Dennehy Marc Grapey James Harms John Hoogenakker Salvatore Inzerillo John Judd Nathan Lane Andrew Long Larry Neumann, Jr. -

17/18 the Winter’S Tale

The Winter’s Tale Presented by Introducing the New Fragrance 17/18 #TheWintersTaleNBC national.ballet.ca The Winter’s Tale Presented by Introducing the New Fragrance Contents 6 Cast 8 Synopsis 10 A Note on the Ballet 12 Selected Biographies 16 Dancers 22 Soaring Campaign The National Ballet of Canada Programme Principal Dancer Editors: Julia Drake and Belinda Bale Harrison James Design: Carmen Wagner Printing: Sunview Press Cover: Piotr Stanczyk and Hannah Fischer. Photos by Karolina Kuras. The Winter’s Tale Choreography: Christopher Wheeldon Staged by: Jacquelin Barrett Scenario: Christopher Wheeldon and Joby Talbot Music: Joby Talbot By arrangement with G. Schirmer, INC. publisher and copyright owner. Designs: Bob Crowley Lighting Design: Natasha Katz Projection Design: Daniel Brodie Silk Effects Design: Basil Twist Répétiteurs: Mandy-Jayne Richardson and Lindsay Fischer Premiere: The Royal Ballet, Covent Garden, London, UK, April 10, 2014 The National Ballet of Canada Premiere: November 14, 2015 Lead philanthropic support for The Winter’s Tale is provided by The Catherine and Maxwell Meighen Foundation, Richard M. Ivey, C.C., an anonymous friend of the National Ballet and The Producers’ Circle. The Producers’ Circle: Gail & Mark Appel, John & Claudine Bailey, Inger Bartlett & Marshal Stearns, David W. Binet, Susanne Boyce & Brendan Mullen, Gail Drummond & Bob Dorrance, Sandra Faire & Ivan Fecan, Kevin & Roger Garland, The William & Nona Heaslip Foundation, Rosamond Ivey, Hal Jackman Foundation, Anna McCowan-Johnson & Donald K. Johnson, O.C., Judy Korthals & Peter Irwin, Judith & Robert Lawrie, Mona & Harvey Levenstein, Jerry & Joan Lozinski, The Honourable Margaret Norrie McCain, C.C., Julie Medland, Sandra Pitblado & Jim Pitblado, C.M., Lynda & Jonas Prince, Susan Scace & Arthur Scace, C.M., Q.C., Gerald Sheff & Shanitha Kachan, Sandra Simpson and Noreen Taylor, C.M. -

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS TLCC Map – Sessions, Labs, and Meals ...............................................................................Inside Front Cover About the Tessitura Network ................................................................................................................................. ii TLCC2015 Agenda ................................................................................................................................................... 1 Tips & Tricks ........................................................................................................................................................... 70 TLCC2015 Planning Committee ......................................................................................................................... 71 Tessitura Network Staff & Board of Directors ................................................................................................ 73 New Organizations since 2014 ............................................................................................................................. 81 Tessitura Lab ............................................................................................................................................................ 82 Sponsor Lab ............................................................................................................................................................. 83 Tessitura Technology Roadmap .......................................................................................................................... -

A Midsummer Night's Dream 3.6 – 3.12.Indd 1 1/29/2020 9:24:18 AM March 2020 | Volume 27, No

2020 MARCH A MIDSUMMER PROGRAM 04 NIGHT'S DREAM The people you trust, trust City National. Top Ranked in Client Referrals* “City National helps keep my financial life in tune.” Michael Tilson Thomas Conductor, Educator and Composer Find your way up.SM Visit cnb.com *Based on interviews conducted by Greenwich Associates in 2017 with more than 30,000 executives at businesses across the country with sales of $1 million to $500 million. City National Bank results are compared to leading competitors on the following question: How likely are you to recommend (bank) to a friend or colleague? City National Bank Member FDIC. City National Bank is a subsidiary of Royal Bank of Canada. ©2018 City National Bank. All Rights Reserved. cnb.com 7275.26 Engaging and eclectic in the East Bay. Oakland is the gateway to the East Bay with a little bit of everything to offer, and St. Paul’s Towers gives you easy access to it all. An artistic, activist, and intellectual Life Plan Community, St. Paul’s Towers is known for convenient services, welcome comforts and security for the future. With classes, exhibits, lectures, restaurants, shops and public transportation within walking distance, St. Paul’s Towers is urban community living at its best. Get to know us and learn more about moving to St. Paul’s Towers. For information, or to schedule a visit, call 510.891.8542. 100 Bay Place, Oakland, CA 94610 www.covia.org/st-pauls-towers A not-for-profit community owned and operated by Covia. License No. 011400627 COA# 327 Untitled-3 1 12/11/19 12:50 PM One team with a singular goal: your real estate success. -

Ticketing, Programming, & Marketing in the Arts

The Move to MOBILE Ticketing, Programming, & Marketing in the Arts November 2016 Introduction The world has gone mobile, and arts organizations are adapting—some more quickly than others. According to Google’s recent “cross-device” research, daily time spent on mobile platforms far outdistances that on desk top computers. So if you depend on your website for marketing, ticket sales, good PR, or any of the other key elements to survival, you better make sure its design is responsive to all platforms, especially the ones with the smaller screens. CONTENTS Our goal in this issue is to provide some guidance to that end, culled from talking 2 Introduction to technology gurus accustomed to working with arts organizations and with groups large (New York’s Lincoln Center) and small (the Maryland Symphony) that 4 Mobile Preferences among have been through the process and can offer experiential advice. Going Mobile: Arts Patrons The Options describes the alternatives available, from creating an app to investing in responsive web design, or, for a good stop-gap, simply making your extant 6 Going Mobile: The Options site mobile friendly. We also provide a list of vendors who specialize in this kind of work, as well as information on the compatibility of their expertise with your 10 Going Mobile: A Few Vendor s current setup. 12 Redesigning with Mobile In a sterling example of learning lessons already paid for and tested by the in Mind commercial sector, several members of Lincoln Center’s marketing staff took a field trip out to Levi’s Stadium, home of the San Francisco 49ers, said to be the 17 Making the Switch to most digitally connected stadium in the world. -

Attendee List As of 11/14/2013 Alphabetical by Name

Attendee List As of 11/14/2013 Alphabetical by Name Anna Ables Tara Aesquivel Director of Marketing and Public Relations Advisory Board The Theatre School at DePaul University Emerging Arts Leaders/Los Angeles Chicago, IL Carson, CA (773)325-7938 (816)806-4831 [email protected] [email protected] www.theatreschool.depaul.edu www.ealla.org @tarajaes Salvador Acevedo ** Principal Elaine S. Akin Contemporanea Communications Director San Francisco, CA Thea Foundation (415)404-6982 North Little Rock, AR [email protected] (501)379-9512 www.contemporanea.us [email protected] theafoundation.org Yasmin A. Acosta-Myers Portland, OR Paula Alekson (406)925-0992 Artistic Engagement Manager [email protected] McCarter Theatre Princeton, NJ Thomas Adkins (609)332-5396 Associate Director of Marketing and Public [email protected] Relations www.mccarter.org Theatre Development Fund New York, NY Alex Alexander (212)912-9770 (321) Student [email protected] Western Michigan University Dept. of Theatre www.tdf.org Kalamazoo, MI (269)387-3220 [email protected] Exhibitor * Presenter ** 1 Attendee List As of 11/14/2013 Alphabetical by Name Dale Allison Francine M. Andersen ** Manager, Business Development Chief of Arts Education Laura Murray Public Relations Miami-Dade County Department of Cultural Vancouver, BC Affairs (604)558-2400 (506) Miami, FL [email protected] (305)375-5024 www.lauramurraypr.com [email protected] @LauraMurrayPR www.miamidadearts.org Sarah A. Altermatt Debra Anderson Director of Public Events Box -

Margaret Alkek Williams Jubilee of Dance | December 6, 2019 MARGARET ALKEK WILLIAMS JUBILEE of DANCE CONTENTS

HoustonBallet Margaret Alkek Williams Jubilee of Dance | December 6, 2019 MARGARET ALKEK WILLIAMS JUBILEE OF DANCE CONTENTS FEATURES 5 FIRST POSITION A look at Houston Ballet’s celebrated history, an upcoming tour, and Houston Ballet supporters on art and planned giving 8 DEAR MARGARET A thank you to the force behind this evening’s performance from Executive Director Jim Nelson 9 MARGARET ALKEK WILLIAMS JUBILEE OF DANCE The repertoire and artists behind the outstanding one-night-only showcase Preferred Jewelry Partner of Houston Ballet Connell B. by Photo IN THIS ISSUE Esmeralda Pas de Deux. Pas Esmeralda 18 Artistic Profiles 19 Company Profiles 23 Houston Ballet Orchestra 25 Annual Supporters Janie Parker and William Pizzuto in Ben Stevenson’s in Ben Stevenson’s and William Pizzuto Janie Parker 2 HOUSTON BALLET HOUSTON BALLET 3 4310 WESTHEIMER RD · WWW.TENENBAUMJEWELERS.COM · 713.629.7444 FIRST POSITIONUPLIFT p. 6 | ANATOMY OF A SCENE p. 7 | EN POINTE p. 8 Tickets Start at $25! And Many More... The history behind Houston Ballet’s 50th birthday AMBITION, CREATIVE SPIRIT, AND INNOVATION can each be used to describe Houston. Quite literally, it’s a “shoot for the moon” kind of city, so it’s no wonder its ballet company has followed suit. From simple beginnings to world stages, Houston Ballet forged its path with grace, style, and sheer determination. 1966-1969 In 1966, Houston Ballet, under the direction of Russian ballerina Nina Popova, planned a limited run performance. Students were trained to perform Giselle alongside ballet superstars Carla Fracci and Erik Bruhn. The performance was a hit and revealed a thirst for ballet in Houston.