History of the 7Th Infantry Division

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RUSI of NSW Article

Jump TO Article The article on the pages below is reprinted by permission from United Service (the journal of the Royal United Services Institute of New South Wales), which seeks to inform the defence and security debate in Australia and to bring an Australian perspective to that debate internationally. The Royal United Services Institute of New South Wales (RUSI NSW) has been promoting informed debate on defence and security issues since 1888. To receive quarterly copies of United Service and to obtain other significant benefits of RUSI NSW membership, please see our online Membership page: www.rusinsw.org.au/Membership Jump TO Article USI Vol61 No2 Jun10:USI Vol55 No4/2005 21/05/10 1:31 PM Page 24 CONTRIBUTED ESSAY Conflict in command during the Kokoda campaign of 1942: did General Blamey deserve the blame? Rowan Tracey General Sir Thomas Blamey was commander-in-chief of the Australian Military Forces during World War II. Tough and decisive, he did not resile from sacking ineffective senior commanders when the situation demanded. He has been widely criticised by more recent historians for his role in the sackings of Lieutenant-General S. F. Rowell, Major-General A. S. Allen and Brigadier A. W. Potts during the Kokoda Campaign of 1942. Rowan Tracey examines each sacking and concludes that Blameyʼs actions in each case were justified. On 16 September 1950, a small crowd assembled in High Command in Australia in 1942 the sunroom of the west wing of the Repatriation In September 1938, Blamey was appointed General Hospital at Heidelberg in Melbourne. The chairman of the Commonwealth’s Manpower group consisted of official military representatives, Committee and controller-general of recruiting on the wartime associates and personal guests of the central recommendation of Frederick Shedden, secretary of figure, who was wheelchair bound – Thomas Albert the Department of Defence, and with the assent of Blamey. -

The Graybeards Magazine Vol. 8 No. 3 June 1994

AMERICA ' S FORGOTTEN VICTORY! OREANWAR TERANS ASSOCIATION THE GRAYBEARDS VOL 8 NO 3 JUNE. 1994 t, Korean War Veterans Association, Inc. BW<RA!E P.O. Box 127 u.s. f'()SlAGE Caruthers CA 93609 PAID , PERMIT NO. 328 MEilRIFIELD, VA FORWARDING AND ADDR.IlSS CORRllCl10N • TIJE GRAYBEARDS June. 1994 NATIONAL OFFICERS l'res.ideot: DICK ADAMS P.O. Box 127, Caruthers, CA 93609 (209-864-3196) (209-268-1869) 1st Vice President: NICHOLAS J. PAPPAS 209 Country Club Drive, Rehobolh Beach, DE 19971 (302-227-3675) 2nd Vice President: HARRY WAllACE Home--514 South Clinton Street; Baltimore, MD 21224 THE GI?AYBEAROS (410-327-4854) (FAX: 410-327-0619) Secretary-Treasurer: ROGER SCALF • 6040 Highbanks, Mascoutah, IL 62258 (618-566-8701) EDITOR - Sherman Pratt (FAX: 618-566-4658) (l.S00-843-5982/THE KWVA) lAYOUT· Nancy Monson, '~JWord Processing Founder and Post President: WILLIAM NORRIS PRINTER - David Park, Giant Printing Co., Inc. BOARD OF DIRECTORS CONTENTS •1991-1994• PRESIDENT'S MESSAGE ....•..•• 1 LEONARD DUBE; 410 Fuostoll Ave.; Torriagton, Cf 06790-6223 EDITORIAL ....•.•.•••••••.•.• 2 (203·439.:)389) BllL COE; 59 ltaox Ave.; Cohots, NY 12047 BRONZE STAR/KOREAN VETS? .. 3 (518-235.0194) LETrERS .................... 4 LT. COL. l>ONALO M. 8Y£RS; 3475 Lyon P.ut 0 .; Woodbridge, FEATURE ARTICLES .•.......•• 5-11 VA 22192 (703-491-7120) (1994--Five Months) ANNOUNCEMENTS, ETC..... •.. 12-13 ED CRYC1£lt; 136 CeattaJ Avenue; S&ateo lslud, NY 10003 MISCELLANEOUS LETTERS 14-18 . (718·981-3630) KWVA CHAPTER NEWSLETTER .. 20 •1992-1995• SOME KWVA MEMBER OP!l'fiONS 21-22 EMME"IT BENJAMIN; 12431 S.W. -

Fall 2006 an Incident in Bataan Lt

Philippine Scouts Heritage Society Preserving the history, heritage, and legacy of the Philippine Scouts for present and future generations Fall 2006 An Incident in Bataan Lt. Col. Frank O. Anders, the S-2 (intelligence) officer, for the 57th Infantry is now deceased. He distinguished himself during the defense of Bataan by frequently infiltrating behind Japanese lines collecting intelligence. For his courage, he received a Bronze Star with Oak Leaf Cluster. Surviving combat and POW incarceration, he wrote “Bataan: An Incident” in 1946 while recovering from injuries that would lead to his retirement shortly thereafter. His family connection to the Philippines stretched over two generations, as Anders’ father served in Manila during the Spanish American War, receiving a Medal of Honor, the nation’s highest military award for valor in combat. In 1961 father and son visited the Philippines together to retrace the paths each had taken in his own war. Because of its length, the Anders article will be serialized over two issues. It also is being published in the current issue of the Bulletin of the American Historical Collection, Ateneo de Manila University in the Philippines. Editor by Lt. Col. Frank O. Anders land—terraced paddies yellow with rip- the China Sea northwest of the Island For 250 years or more the solid ado- ened grain. Beyond were the solid of Luzon in the Philippines. be stone church had withstood the rav- walled fields of cane, higher and more ages of nature and man. Earthquake, fire, rolling. And above, looking out over The Zambales looked down, as they tidal wave and typhoon had battered and cane and rice and church, with its town, had looked down for centuries, while marred the structure, but still it stood, its fringe of fish ponds, and then the first Moro pirates, then Chinese adven- lofty and secure, with its stone terraces bay—looking down on this and the turers, then Spanish Conquistadores and and latticed, stone-walled courtyard. -

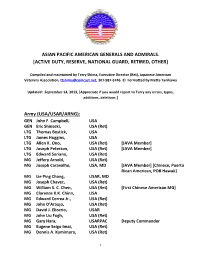

14 Sept 13 Generals and Admirals. List by Services

ASIAN PACIFIC AMERICAN GENERALS AND ADMIRALS. [ACTIVE DUTY, RESERVE, NATIONAL GUARD, RETIRED, OTHER] Compiled and maintained by Terry Shima, Executive Director (Ret), Japanese American Veterans Association, [email protected], 301-987-6746. © Formatted by Metta Tanikawa Updated: September 14, 2013, [Appreciate if you would report to Terry any errors, typos, additions, deletions.] Army (USA/USAR/ARNG): GEN John F. Campbell, USA GEN Eric Shinseki, USA (Ret) LTG Thomas Bostick, USA LTG James Huggins, USA LTG Allen K. Ono, USA (Ret) [JAVA Member] LTG Joseph Peterson, USA (Ret) [JAVA Member] LTG Edward Soriano, USA (Ret) MG Jeffery Arnold, USA (Ret) MG Joseph Caravalho, USA, MD [JAVA Member] [Chinese, Puerto Rican American, POB Hawaii] MG Lie Ping Chang, USAR, MD MG Joseph Chavez, USA (Ret) MG William S. C. Chen, USA (Ret) [First Chinese American MG] MG Clarence K.K. Chinn, USA MG Edward Correa Jr., USA (Ret) MG John D’Araujo, USA (Ret) MG David J. Elicerio, USAR MG John Liu Fugh, USA (Ret) MG Gary Hara, USARPAC Deputy Commander MG Eugene Seigo Imai, USA (Ret) MG Dennis A. Kamimura, USA (Ret) 1 MG Jason K. Kamiya, USA [JAVA Member] MG Theodore S. Kanamine, USA (Ret) MG Rodney Kobayashi, USAR (Ret) [JAVA Member] MG Calvin Kelly Lau, USA (Ret) MG Robert G.F. Lee, USA (Ret) MG Alexis T. Lum, USA (Ret) [passed away 28 Aug 2009] MG John G.H. Ma, USAR, USARPAC MG Vern T. Miyagi, USA (Ret) MG Bert Mizusawa, USAR [JAVA Member] MG James Mukoyama, USA (Ret) [JAVA Member] MG Michael K. Nagata, USA MG Benny Paulino, USA (Ret) MG Eldon Regua, USA (Ret) MG Walter Tagawa, USA (Ret) MG Antonio Taguba, USA (Ret) MG Stephen Tom, USAR MG Ming T. -

Army (USA/USAR/ARNG): GEN John F. Campbell, USA (J ) GEN Eric

ASIAN PACIFIC AMERICAN GENERALS AND ADMIRALS. [ACTIVE DUTY, RESERVE, NATIONAL GUARD, RETIRED, OTHER] Created by MG Anthony Taguba, USA (Ret) and Terry Shima. Updated: April 21, 2017. [Appreciate if you would report to Terry Shima ([email protected]) and Beth (webmaster: [email protected]) any errors, typos, additions, deletions. Thank you.] Army (USA/USAR/ARNG): GEN John F. Campbell, USA (J ) GEN Eric Shinseki, USA, Ret (J ) LTG Thomas Bostick, USA [JAVA Member] (J ) LTG James Huggins, USA [JAVA Member] (J ) LTG Paul Nakasone, USA [JAVA Member] (J ) LTG Allen K. Ono, USA, Ret [JAVA Member] (J ) LTG Joseph Peterson, USA. [JAVA member] (P= Pacific) LTG Edward Soriano, USA, Ret. (F ) MG Jeffery Arnold, USA (Ret) (P ) MG John D’Araujo, ARNG, Ret (P ) MG Joseph Caravalho, USA. MD. [JAVA member] [POB Hawaii] (P ) MG Lie Ping Chang, USAR, MD (C ) MG Joseph James Chavez, ARNG (P) MG William S. C. Chen, USA, Ret. [First Chinese American MG] (C ) MG Clarence K.K. Chinn, USA [Promoted 9.22.09] [JAVA Member] (C ) MG Edward L. Correa, Jr, HIARNG, Ret (P ) MG David J. Elicerio, USAR (F ) MG John Liu Fugh, USA, JAG, Ret (C ) MG Gary Hara, HIARNG (J ) (Brother of BG Kenneth Hara) 1 MG Eugene Seigo Imai, USA, Ret. (J ) MG Dennis A. Kamimura, ARNG, Ret (J ) MG Jason K. Kamiya, USA [JAVA member] (J ) MG Theodore S. Kanamine, USA, Ret. (J ) MG Rodney Kobayashi, USA, Ret. [JAVA Member] (J ) MG Calvin Kelly Lau, USA, Ret. (C ) MG Caryl Lee, USAFR (C ) MG Robert G.F. Lee, HIARNG. -

South-West Pacific: Amphibious Operations, 1942–45

Issue 30, 2021 South-West Pacific: amphibious operations, 1942–45 By Dr. Karl James Dr. James is the Head of Military History, Australian War Memorial. Issue 30, 2021 © Commonwealth of Australia 2021 This work is copyright. You may download, display, print, and reproduce this material in unaltered form only (retaining this notice and imagery metadata) for your personal, non- commercial use, or use within your organisation. This material cannot be used to imply an endorsement from, or an association with, the Department of Defence. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, all other rights are reserved. Issue 30, 2021 On morning of 1 July 1945 hundreds of warships and vessels from the United States Navy, the Royal Australian Navy (RAN), and the Royal Netherlands Navy lay off the coast of Balikpapan, an oil refining centre on Borneo’s south-east coast. An Australian soldier described the scene: Landing craft are in formation and swing towards the shore. The naval gunfire is gaining momentum, the noise from the guns and bombs exploding is terrific … waves of Liberators [heavy bombers] are pounding the area.1 This offensive to land the veteran 7th Australian Infantry Division at Balikpapan was the last of a series amphibious operations conducted by the Allies to liberate areas of Dutch and British territory on Borneo. It was the largest amphibious operation conducted by Australian forces during the Second World War. Within an hour some 16,500 troops were ashore and pushing inland, along with nearly 1,000 vehicles.2 Ultimately more than 33,000 personnel from the 7th Division and Allied forces were landed in the amphibious assault.3 Balikpapan is often cited as an example of the expertise achieved by Australian forces in amphibious operations during the war.4 It was a remarkable development. -

The Final Campaigns: Bougainville 1944-1945

University of Wollongong Thesis Collections University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Year The final campaigns: Bougainville 1944-1945 Karl James University of Wollongong James, Karl, The final campaigns: Bougainville 1944-1945, PhD thesis, School of History and Politics, University of Wollongong, 2005. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/467 This paper is posted at Research Online. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/467 The Final Campaigns: Bougainville 1944-1945 A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree Doctor of Philosophy from University of Wollongong by Karl James, BA (Hons) School of History and Politics 2005 i CERTIFICATION I, Karl James, declare that this thesis, submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy, in the School of History and Politics, University of Wollongong, is wholly my work unless otherwise referenced or acknowledged. The document has not been submitted for qualifications at any other academic institution. Karl James 20 July 2005 ii Table of Contents Maps, List of Illustrations iv Abbreviations vi Conversion viii Abstract ix Acknowledgments xi Introduction 1 1 ‘We have got to play our part in it’. Australia’s land war until 1944. 15 2 ‘History written is history preserved’. History’s treatment of the Final Campaigns. 30 3 ‘Once the soldier had gone to war he looked for leadership’. The men of the II Australian Corps. 51 4 ‘Away to the north of Queensland, On the tropic shores of hell, Stand grimfaced men who watch and wait, For a future none can tell’. The campaign takes shape: Torokina and the Outer Islands. -

The Battle of Messines

CHAPTER XV THE BATTLE OF MESSINES-JUNE 7TH BEFOREmost great attacks on the Western Front, during that critical last night in which, generally, the infantry left its billets and made its way, first, in column of fours on dark roads beside moving wheel and motor traffic, then, usually in file, along tracks marked across the open, and finally into communication trenches to wind silently out in the small hours and line the “ jumping-off ” trenches or white tapes laid in the long wet grass of open No-Man’s Land, where for an hour or two it must await the signal to assault-during these critical hours one thought was usually uppermost in the men’s minds: does the enemy know? With the tactics of 1917,involving tremendous preparatory bombardments, which entailed months of preliminary railway and road construction, G.H.Q. had been forced to give up the notion of keeping an attack secret until it was delivered. Enemy airmen could not fail to observe these works and also the new camps, supply centres, casualty clearing stations, hangars for aeroplanes. Reference has been made to the Comniander-in-Chief’s desire to impart the impression, in April, of a serious attack, and,‘in May, of a feint. But the final week’s bombardment had given sure notice of the operation, and the most that could be hoped for was that the enemy might be deceived as to the main stroke that would come after, and might continue to expect it at Arras rather than at Ypres. As far as the Messines offensive went, the Germans must know that a great attack-whether feint or principal operation-was imminent ; indeed, German prisoners spoke with certainty of it. -

The 42Nd ASMS Conference on Mass Spectrometry May 29 –

The 42nd ASMS Conference on Mass Spectrometry May 29 - June 3, 1994 Hyatt Regency Hotel, Chicago, Illinois Preliminary Program The title information listed in this program is provided directly by the authors and is not edited. For additional information, contact ASMS (505) 989-4517 SUNDAY Matrix and Polypeptide Ions Produced by Matrix 03:00 Registration Assisted Laser Desorption; "Zhang, Wenzhu; Chait, 07:00 Workshop: Young Mass Spectrometrists Brian T.;The Rockefeller University, New York, N.Y. 08:00 Welcome Mixer 10021 USA. 12:10 Influence of the laser beam angle of incidence on MONDAY ORAL SESSIONS molecular ion ejection in MALDI. Influence of the 08:30 Plenary Lecture: Dr. Susan Solomon, NOAA, laser baem angle of incidence on molecular ion Boulder, CO; speaking on ozone depletion and ejection in MALDI.; 'Chaurand,P IPN ORSAY; upper atmosphere chemistry. Della Negra.S IPN ORSAY; Deprun, C TI'N ORSAY; Hoyes,J VG MANCHESTER; Le Beyec,Y IPN ORSAY; lPN ORSAY 91406 FRANCE, VG Analytical Laser Desorption Ionization Manchester M23 9LE ENGLAND. 09:30 The Role of the Matrix in Matrix-Assisted Laser 12:30 Lunch Break Desorption Ionization: What We Know Versus 04:00 What makes a matrix work for UV-MALDI-MS; What We Understand; "Russell, David H.; 'Karas, Michael; Bahr, Ute; Hahner, Stephanie; Stahl, Department of Chemistry, Texas A&M University, Bernd; Strupat, Keratin: Hillenkamp, Franz; lnst. for College Station, TX, 77843. Med. Physics & Biophysics, 48149 Mnnster, FR 09:50 Mechanisms in laser ablation mass spectrometry Germany. of large molecules: questions and some answers; 04:20 Mixing Matrices: Attempting to Construct Effective "Williams, Peter; Department of Chemistry, Composite Materials for MALDI; "BeaviS, Ronald Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ 85287-1604. -

An Interview with Bernie Goulet Part of the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library Veterans Remember Oral History Project Interview # VRK-A-L-2009-001

Title Page & Abstract An Interview with Bernie Goulet Part of the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library Veterans Remember Oral History project Interview # VRK-A-L-2009-001 Bernie Goulet, a Korean War veteran serving with the U.S. Army’s 7th Division during the Inchon landing, the Chosin Reservoir and the Chinese Spring Offensive, was interviewed on the dates listed below as part of the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library’s Veteran’s Remember Oral History project. Interview dates & location: Date: January 6, 2009 Location: Goulet residence, Springfield, Illinois Date: January 22, 2009 Location: Goulet residence Date: June 11, 2009 Location: Goulet residence Interview Format: Digital audio Interviewer: Mark R. DePue, ALPLM Volunteer Transcription by: Tape Transcription Center, Boston, MA Edited by: Cheryl Wycoff and Rozanne Flatt, Volunteers, ALPL Total Pages: 113 Total Times: 2:20 + 3:05 + 19 min/2.33 + 3.08 + .32 = 5.73 hrs Session 1: Early life through action at the Chosin Reservoir during Korean War Session 2: Korean War action with 7th In Division in winter and spring of 1951 Session 3: Two stories from Korea Accessioned into the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library Archives on 06/16/2009. The interviews are archived at the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library in Springfield, Illinois. © 2009 Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library Abstract Bernie Goulet, Veterans Remember , VRK-A-L-2009-001 Biographical Information Overview of Interview: Bernie Goulet was born on April 22nd, 1931 in Springfield, Illinois. Bernie grew up in Springfield during the Great Depression, and had many memories as a young boy during the Second World War, having two older brothers in the service. -

Network-Centric Operations Case Study: the Stryker Brigade Combat Team

THE ARTS This PDF document was made available CHILD POLICY from www.rand.org as a public service of CIVIL JUSTICE the RAND Corporation. EDUCATION ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT Jump down to document6 HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit NATIONAL SECURITY research organization providing POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY objective analysis and effective SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY solutions that address the challenges SUBSTANCE ABUSE facing the public and private sectors TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY around the world. TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE WORKFORCE AND WORKPLACE Support RAND Purchase this document Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore RAND National Defense Research Institute View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non- commercial use only. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents. This product is part of the RAND Corporation monograph series. RAND monographs present major research findings that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND mono- graphs undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for research quality and objectivity. Network-Centric Operations Case Study The Stryker Brigade Combat Team Daniel Gonzales, Michael Johnson, Jimmie McEver, Dennis Leedom, Gina Kingston, Michael Tseng Prepared for the Office of Force Transformation in the Office of the Secretary of Defense Approved for public release; distribution unlimited The research described in this report was prepared for the Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD). -

Seventy-Second Annual Report of the Association of Graduates of the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York, June

SEVENTY-SECOND ANNUAL REPORT of the Association of Graduates of the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York June 10, 1941 C-rinted by The Moore Printing Company, Inc. Newburgh, N. Y¥: 0 C; 42 lcc0 0 0 0 P-,.0 r- 'Sc) CD 0 ct e c; *e H, Ir Annual Report, June 10, 1941 3 Report of the 72nd Annual Meeting of the Association of Graduates, U. S. M. A. Held at West Point, N. Y., June 10, 1941 1. The meeting was called to order at 2:02 p. m. by McCoy '97, President of the Association. There were 225 present. 2. Invocation was rendered by the Reverend H. Fairfield Butt, III, Chaplain of the United States Military Academy. 3. The President presented Brigadier General Robert L. Eichel- berger, '09, Superintendent, U. S. Military Academy, who addressed the Association (Appendix B). 4. It was moved and seconded that the reading of the report of the President be dispensed with, since that Report would later be pub- lished in its entirety in the 1941 Annual Report (Appendix A). The motion was passed. 5. It was moved and seconded that the reading of the Report of the Secretary be dispensed with, since that Report would later be pub- lished in its entirety in the 1941 Annual Report (Appendix C.) The motion was passed. 6. It was moved and seconded that the reading of the Report of the Treasurer be dispensed with, since that Report would later be published in its entirety in the 1941 Annual Report (Appendix D).