Network-Centric Operations Case Study: the Stryker Brigade Combat Team

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Armored Medical Units. B

U.S WAR DEPT, AHMQRSD MEDICAL UNITS. Fk 17-80. El Ml WAR DEPARTMENT FIELD MANUAL ARMORED MEDICAL UNITS WAR DEPARTMENT 30 AUGUST 1944 IV A R D E P A R T M E N T FIE L D M A ,V U A L F M 17-80 ARMORED MEDICAL UNITS WA R D E PA R T M E N T ■ 3 0 AUGUST 1944 RESTRICTED, dissemination of restricted infer- motion contained in restricted documents and the essential characteristics of restricted material may be given to any person known to be in the service of the United States and to persons of undoubted loyalty and discretion who are cooperating in Government work, but will not be communicated to the public or to the press except by authorized military public relations agencies (See also par. 23b, AR 380-5, 1 5 Mar 1944.) United States Government Printing Office Washington: 1944 WAR DEPARTMENT, Washington 25, D.C., 30 August 1944. EM 17-80, Armored Field Manual, Medical Units, Ar- mored, is published for the information and guidance of all concerned. [A.G. SCO.7 (28 Jul 44).] order of the Secretary of War G. C. MARSHALL, Chief of Staff. Official: J. A. ULIO, Major General, The Adjutant General, Distribution : As prescribed in paragraph 9a, FM 21-6 except Gen & Sp Sv Schs (5) except Armd Sch (400), D 2, 7(5), 17(10); Bn 17(20); I Bn 2(25), 5(15), 6(20), 7(20), 8(60), 9(15); IC 6, 11, 17(5). IBn2:T/0&E 2-25; I Bn 5: T/O & E 5-215; I Bn 6: T/O &E 6-165; IBn7:T/0&E 7-25; I Bn 8: T/O &E 8-75; IBn9:T/0&E 9-65; IC 6: T/O & E 6-160-1; IC 11: T/O &E 11-57; IC 17: T/O & E 17-20-1; 17-22; 17-60-1. -

Fm 6-02 Signal Support to Operations

FM 6-02 SIGNAL SUPPORT TO OPERATIONS SEPTEMBER 2019 DISTRIBUTION RESTRICTION: Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited. This publication supersedes FM 6-02, dated 22 January 2014. HEADQUARTERS, DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY This publication is available at the Army Publishing Directorate site (https://armypubs.army.mil/) and the Central Army Registry site (https://atiam.train.army.mil/catalog/dashboard). *FM 6-02 Field Manual Headquarters No. 6-02 Department of the Army Washington, D.C., 13 September 2019 Signal Support to Operations Contents Page PREFACE..................................................................................................................... v INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................ vii Chapter 1 OVERVIEW OF SIGNAL SUPPORT ........................................................................ 1-1 Section I – The Operational Environment ............................................................. 1-1 Challenges for Army Signal Support ......................................................................... 1-1 Operational Environment Overview ........................................................................... 1-1 Information Environment ........................................................................................... 1-2 Trends ........................................................................................................................ 1-3 Threat Effects on Signal Support ............................................................................. -

4Th Infantry Division Rear Detachment and FRG Training Scenarios

4th Infantry Division Rear Detachment and FRG Training Scenarios November 2017 DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY HEADQUARTERS, 4TH INFANTRY DIVISION AND FORT CARSON 6105 WETZEL AVENUE, BUILDING 1435 FORT CARSON, COLORADO 80913-4289 REPLY TO ATTENTION OF: AFYB-SGS 17 November 2017 MEMORANDUM FOR RECORD SUBJECT: Rear Detachment Training Scenarios 1. Purpose: These scenarios are intended to be used as training exercises for your Rear Detachment and Family Readiness Group Senior Advisors. They are real world crises units have had to deal with during deployments. Rear Detachments, along with their FRG Advisors, are encouraged to use these scenarios to stimulate discussion and consider what SOPs may be useful to ensure that similar situations within their unit are handled properly, quickly, and consistently. 2. The Division Family Readiness Liaison (FRL) maintains a site on the 4ID portal where unit FRL’s can find templates, forms, training resources and other family-related information. Access this site at: https://army.deps.mil/Army/cmds/4id/CG/SitePages/FRL.aspx. Use your email certificate to log in. 3. The Division FRL stands ready to assist Brigade level Rear Detachments plan and execute this scenario training. 4. The point of contact for this memorandum is the undersigned at 719-503-0012 or [email protected] ALEXANDER H. CHUNG CPT, GS Family Readiness Liaison 4th Infantry Division Rear Detachment and FRG Training Scenarios TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Quick Reference Phone Numbers 2. Acronym Explanations 3. Category Breakdown For Scenarios -

Fall 2006 an Incident in Bataan Lt

Philippine Scouts Heritage Society Preserving the history, heritage, and legacy of the Philippine Scouts for present and future generations Fall 2006 An Incident in Bataan Lt. Col. Frank O. Anders, the S-2 (intelligence) officer, for the 57th Infantry is now deceased. He distinguished himself during the defense of Bataan by frequently infiltrating behind Japanese lines collecting intelligence. For his courage, he received a Bronze Star with Oak Leaf Cluster. Surviving combat and POW incarceration, he wrote “Bataan: An Incident” in 1946 while recovering from injuries that would lead to his retirement shortly thereafter. His family connection to the Philippines stretched over two generations, as Anders’ father served in Manila during the Spanish American War, receiving a Medal of Honor, the nation’s highest military award for valor in combat. In 1961 father and son visited the Philippines together to retrace the paths each had taken in his own war. Because of its length, the Anders article will be serialized over two issues. It also is being published in the current issue of the Bulletin of the American Historical Collection, Ateneo de Manila University in the Philippines. Editor by Lt. Col. Frank O. Anders land—terraced paddies yellow with rip- the China Sea northwest of the Island For 250 years or more the solid ado- ened grain. Beyond were the solid of Luzon in the Philippines. be stone church had withstood the rav- walled fields of cane, higher and more ages of nature and man. Earthquake, fire, rolling. And above, looking out over The Zambales looked down, as they tidal wave and typhoon had battered and cane and rice and church, with its town, had looked down for centuries, while marred the structure, but still it stood, its fringe of fish ponds, and then the first Moro pirates, then Chinese adven- lofty and secure, with its stone terraces bay—looking down on this and the turers, then Spanish Conquistadores and and latticed, stone-walled courtyard. -

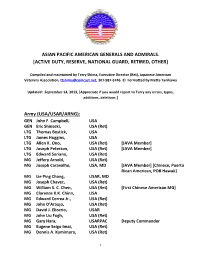

14 Sept 13 Generals and Admirals. List by Services

ASIAN PACIFIC AMERICAN GENERALS AND ADMIRALS. [ACTIVE DUTY, RESERVE, NATIONAL GUARD, RETIRED, OTHER] Compiled and maintained by Terry Shima, Executive Director (Ret), Japanese American Veterans Association, [email protected], 301-987-6746. © Formatted by Metta Tanikawa Updated: September 14, 2013, [Appreciate if you would report to Terry any errors, typos, additions, deletions.] Army (USA/USAR/ARNG): GEN John F. Campbell, USA GEN Eric Shinseki, USA (Ret) LTG Thomas Bostick, USA LTG James Huggins, USA LTG Allen K. Ono, USA (Ret) [JAVA Member] LTG Joseph Peterson, USA (Ret) [JAVA Member] LTG Edward Soriano, USA (Ret) MG Jeffery Arnold, USA (Ret) MG Joseph Caravalho, USA, MD [JAVA Member] [Chinese, Puerto Rican American, POB Hawaii] MG Lie Ping Chang, USAR, MD MG Joseph Chavez, USA (Ret) MG William S. C. Chen, USA (Ret) [First Chinese American MG] MG Clarence K.K. Chinn, USA MG Edward Correa Jr., USA (Ret) MG John D’Araujo, USA (Ret) MG David J. Elicerio, USAR MG John Liu Fugh, USA (Ret) MG Gary Hara, USARPAC Deputy Commander MG Eugene Seigo Imai, USA (Ret) MG Dennis A. Kamimura, USA (Ret) 1 MG Jason K. Kamiya, USA [JAVA Member] MG Theodore S. Kanamine, USA (Ret) MG Rodney Kobayashi, USAR (Ret) [JAVA Member] MG Calvin Kelly Lau, USA (Ret) MG Robert G.F. Lee, USA (Ret) MG Alexis T. Lum, USA (Ret) [passed away 28 Aug 2009] MG John G.H. Ma, USAR, USARPAC MG Vern T. Miyagi, USA (Ret) MG Bert Mizusawa, USAR [JAVA Member] MG James Mukoyama, USA (Ret) [JAVA Member] MG Michael K. Nagata, USA MG Benny Paulino, USA (Ret) MG Eldon Regua, USA (Ret) MG Walter Tagawa, USA (Ret) MG Antonio Taguba, USA (Ret) MG Stephen Tom, USAR MG Ming T. -

ATP 3-57.70. Civil-Military Operations Center

ATP 3-57.70 Civil-Military Operations Center May 2014 DISTRIBUTION RESTRICTION: Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited. FOREIGN DISCLOSURE RESTRICTION (FD 1): The material contained in this publication has been reviewed by the developers in coordination with the United States Army John F. Kennedy Special Warfare Center and School foreign disclosure authority. This product is releasable to students from all requesting foreign countries without restrictions. Headquarters, Department of the Army This publication is available at Army Knowledge Online (https://armypubs.us.army.mil/doctrine/index.html). To receive publishing updates, please subscribe at http://www.apd.army.mil/AdminPubs/new_subscribe.asp. Army Techniques Publication Headquarters, No. 3-57.70 Department of the Army Washington, DC 5 May 2014 Civil-Military Operations Center Contents Page PREFACE..............................................................................................................iv INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................v Chapter 1 OPERATIONS .................................................................................................... 1-1 General ............................................................................................................... 1-1 Unified Land Operations ..................................................................................... 1-2 Decisive Action .................................................................................................. -

Army (USA/USAR/ARNG): GEN John F. Campbell, USA (J ) GEN Eric

ASIAN PACIFIC AMERICAN GENERALS AND ADMIRALS. [ACTIVE DUTY, RESERVE, NATIONAL GUARD, RETIRED, OTHER] Created by MG Anthony Taguba, USA (Ret) and Terry Shima. Updated: April 21, 2017. [Appreciate if you would report to Terry Shima ([email protected]) and Beth (webmaster: [email protected]) any errors, typos, additions, deletions. Thank you.] Army (USA/USAR/ARNG): GEN John F. Campbell, USA (J ) GEN Eric Shinseki, USA, Ret (J ) LTG Thomas Bostick, USA [JAVA Member] (J ) LTG James Huggins, USA [JAVA Member] (J ) LTG Paul Nakasone, USA [JAVA Member] (J ) LTG Allen K. Ono, USA, Ret [JAVA Member] (J ) LTG Joseph Peterson, USA. [JAVA member] (P= Pacific) LTG Edward Soriano, USA, Ret. (F ) MG Jeffery Arnold, USA (Ret) (P ) MG John D’Araujo, ARNG, Ret (P ) MG Joseph Caravalho, USA. MD. [JAVA member] [POB Hawaii] (P ) MG Lie Ping Chang, USAR, MD (C ) MG Joseph James Chavez, ARNG (P) MG William S. C. Chen, USA, Ret. [First Chinese American MG] (C ) MG Clarence K.K. Chinn, USA [Promoted 9.22.09] [JAVA Member] (C ) MG Edward L. Correa, Jr, HIARNG, Ret (P ) MG David J. Elicerio, USAR (F ) MG John Liu Fugh, USA, JAG, Ret (C ) MG Gary Hara, HIARNG (J ) (Brother of BG Kenneth Hara) 1 MG Eugene Seigo Imai, USA, Ret. (J ) MG Dennis A. Kamimura, ARNG, Ret (J ) MG Jason K. Kamiya, USA [JAVA member] (J ) MG Theodore S. Kanamine, USA, Ret. (J ) MG Rodney Kobayashi, USA, Ret. [JAVA Member] (J ) MG Calvin Kelly Lau, USA, Ret. (C ) MG Caryl Lee, USAFR (C ) MG Robert G.F. Lee, HIARNG. -

2Nd INFANTRY REGIMENT

2nd INFANTRY REGIMENT 1110 pages (approximate) Boxes 1243-1244 The 2nd Infantry Regiment was a component part of the 5th Infantry Division. This Division was activated in 1939 but did not enter combat until it landed on Utah Beach, Normandy, three days after D-Day. For the remainder of the war in Europe the Division participated in numerous operations and engagements of the Normandy, Northern France, Rhineland, Ardennes-Alsace and Central Europe campaigns. The records of the 2nd Infantry Regiment consist mostly of after action reports and journals which provide detailed accounts of the operations of the Regiment from July 1944 to May 1945. The records also contain correspondence on the early history of the Regiment prior to World War II and to its training activities in the United States prior to entering combat. Of particular importance is a file on the work of the Regiment while serving on occupation duty in Iceland in 1942. CONTAINER LIST Box No. Folder Title 1243 2nd Infantry Regiment Unit Histories January 1943-June 1944 2nd Infantry Regiment Unit Histories, July-October 1944 2nd Infantry Regiment Histories, July 1944- December 1945 2nd Infantry Regiment After Action Reports, July-September 1944 2nd Infantry Regiment After Action Reports, October-December 1944 2nd Infantry Regiment After Action Reports, January-May 1945 2nd Infantry Regiment Casualty List, 1944-1945 2nd Infantry Regiment Unit Journal, 1945 2nd Infantry Regiment Narrative History, October 1944-May 1945 2nd Infantry Regiment History Correspondence, 1934-1936 2nd Infantry -

Systems Development and Production Issue Area Active Assignments

United States General Accounting Office GAO National Security and International Affairs Julyl1995 Systems Development and Production Issue Area Active Assignments GAO/AA-95-4(3) Foreword This report was prepared primarily to inform Congressional members and key staff of ongoing assignments in the General Accounting Office's Systems Development and Production issue area This report contains assignments that were ongoing as of July 6, 1995, and presents a brief background statement and a list of key questions to be answered on each assignment. The report will be issued quarterly. This report was compiled from information available in GAO'S internal management information systems. Because the information was downloaded from computerized data bases intended for internal use, some information may appear in abbreviated form. If you have questions or would like additional information about assignments listed, please contact Louis Rodrigues, Director; Brad Hathaway, Associate Director; or Thomas Schulz, Associate Director, on (202) 5124841. Page 1 GAO/AA-95-4(3) Contents Page WEAPON SYSTEMS JUSTIFICATION ,MONITORING OPERATIONAL TEST OF B-l1B BOMBER. 1 ,STATUS OF NAVY TACTICAL AIRCRAFT MODERNIZATION EFFORTS. I , EVALUATION OF THE INTEGRATION OF ATCCS INTO THE ARMY BATTLE COMMAND SYSTEM. I , SHALLOW WATER ANTISUBMARINE WARFARE LIGHTWEIGHT TORPEDO. 2 , ACQUISITION OF THE ENHANCED FIBER OPTIC-GUIDED MISSILE (EFOG-M) SYSTEM. 2 , REVIEW OF AV-8B REMANUFACTURE PROGRAM. 2 COMBAT AIR POWER ASSESSMENT--SURVEILLANCE AND RECONNAISSANCE. 3 New , THE NAVY'S EFFORTS TO DEVELOP A COMBAT SYSTEM FOR THE NSSN. 3 New , SURVEY OF B-lB CONVENTIONAL MISSION UPGRADE PROGRAM. 3 WEAPON SYSTEMS ACQUISITION PROCESS , EVALUATION OF THE SERVICES' EFFORTS TO DEVELOP COOPERATIVE IFF SYSTEMS. -

Battle Command on the Move

Battle Command on the Move Authors: Rebecca Morley Chief Joseph Kobsar POC: Rebecca Morley AMSRD-CER-C2-BCS-MD Building 2700 Ft. Monmouth, NJ 07703 Telephone: (732) 532-8927 Fax: (732) 532-8929 [email protected] 1. Abstract Battle Command on the Move (BCOTM) is a revolutionary capability that provides current and future combined arms commanders all of the information resident in their command posts, and the required communications necessary to command and control their combined arms team on the move, or at a short halt, from any vantage point on the joint battlefield. The purpose of the BCOTM effort was to convert five M-7 Bradley Fire Support Team (BFIST) vehicles into BCOTM systems. Three operator workstations and an extensive Mission Equipment Package (MEP) were integrated into the five BFIST platforms to provide a common operational picture and enable Situational Understanding (SU) while on the move. The integration team consisted of three groups who worked together for 2 months to complete the system from the concept until the final hand off to the 4th Infantry Division (ID), Fort Hood, TX. The program was extremely successful and has led to further advancements in battle command on the move. 2. Background 2.1. The Current Battle Command Currently, command and control is conducted from Command Posts (CP). There are three basic areas of battle command; the current fight, future planning, and support. The current fight is the responsibility of the Division Tactical (DTAC) CP, which is usually small and mobile and allows the commander to plan and monitor the battle from a remote location. -

Guardlife V34 N1 Special Pt 2.Pmd

Redlegs train for new mission On Jan. 5, 2004, B Battery, 3rd Battalion, 112th Field Artillery mobilized for deployment in support of Operation Iraqi Freedom. From Jan. 7 to Feb. 21, the Battery underwent military police training at Fort Dix, which included military police weap- ons systems and tasks. The unit then deployed to Kuwait for theater specific training and certification. By March 7, it had moved to Camp Cuervo in Baghdad, Iraq, where it was attached to the 89th Military Police Brigade and operation- ally re-designated as C Company. The company received additional training from the unit it was replacing. C Com- pany Soldiers learned important real-world lessons during 04 Capt. (Chaplain) Kevin Williams (far right), 3rd Battalion, 112th and Christina Lyness; Spc. Kaleb Hazen, 1st Battalion, 172nd Field Field Artillery, presides over a triple wedding at Chapel 5, Fort Dix Artillery, and Megan Finnegan; and Spc. William Donahue, 3-112th on Feb. 15. Married were (l-r): Spc. Glenn Erlenmeyer, 3-112th, and Kerry Chin. Photo by Tech Sgt. Mark Olsen. NJDMAVA/PA this “right seat ride” transition period. tinue patrolling and site security operations. In April, C Company began conducting patrols and pro- From mid-May to early June, C Company engaged in viding site security at Iraqi police stations in eastern Baghdad, fierce combat operations against the Mahdi army of Muqtada including Sadr City. The unit later began training and equip- al-Sadr in Sadr City. When U.S. Soldiers arrived at Iraqi ping Iraqi police at several stations in their area of operations. -

Commander's Column

Serving the Soldiers, Civilians and Families of 2nd BCT, 4th Inf. Div. Issue 43 Jan 27, 2011 2nd STB activates ‘Havoc’ FSC “Today was not just the passing of a guidon from one commander to the next, but the start of a new entity to support the wartime mission Lt. Col. Patrick Stevenson, commander, 2nd Special in Afghanistan” said Capt. Troops Battalion and Capt. Brian Johnson, com- Brian Johnson, commander of mander, Company H present the colors as Sgt. 1st Company H. Class Joseph Kienath, First Sergeant, Company H Special Troops Battalions do uncases their new colors. not traditionally include FSCs, will be the Mission Readiness Exercise at the but the logistical expectations Joint Readiness Training Center. Soldiers for the unit’s upcoming from Company H are scheduled in realistic deployment to Afghanistan were training events at JRTC to ensure they are Lt. Col. Patrick Stevenson, commander, 2nd Special Troops Battalion greater than the Soldiers of the able to transfer their capabilities to the and Capt. Brian Johnson, commander, Company H, lead the activa- battalion could be expected to wartime mission in Afghanistan. tion ceremony after the uncasing of the company’s colors. support, said 1st Lt. Timothy “We are excited to continue to support Story by 1st Lt. Bonnie Hutchinson Green, the executive officer of the Special Troops Battalion,” said Green. “I photos by Staff Sgt. Dennis Hines Company H. see this activation as the perfect opportunity 2nd Special Troops Battalion The company will be pushed hard as they to expand our resources and capabilities in Company H, a forward support company, posture themselves for deployment, said order to accomplish our mission and ensure was activated into the 2nd Special Troops Green.