On Winged Words: an Examination of the Use of Language in the Iliad to Create and Access the Poetic Space

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jewish and Christian Cosmogony in Late Antiquity

Texts and Studies in Ancient Judaism Texte und Studien zum Antiken Judentum Edited by Peter Schäfer (Princeton, NJ/Berlin) Annette Yoshiko Reed (Philadelphia, PA) Seth Schwartz (New York, NY) Azzan Yadin-Israel (New Brunswick, NJ) 155 Jewish and Christian Cosmogony in Late Antiquity Edited by Lance Jenott and Sarit Kattan Gribetz Mohr Siebeck Lance Jenott, born 1980, is a post-doctoral research fellow at the University of Oslo. He studied History, Classics, and Religion at the University of Washington (Seattle) and Princeton University, and holds a PhD in the Religions of Late Antiquity from Princeton University. Sarit Kattan Gribetz, born 1984, is a post-doctoral fellow at the Jewish Theological Semi- nary and Harvard University. She studied Religion, Jewish Studies, and Classics at Prince- ton University, where she earned an AB and PhD in the Religions of Late Antiquity. ISBN 978-3-16-151993-2 ISSN 0721-8753 (Texts and Studies in Ancient Judaism) Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbiblio- graphie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2013 by Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen, Germany, www.mohr.de This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that permitted by copyright law) without the publisher's written permission. This applies particularly to reproductions, translations, microfilms and storage and processing in electronic systems. The book was printed on non-aging paper by Guide-Druck in Tübingen and bound by Großbuchbinderei Spinner in Ottersweier. Printed in Germany. Preface This volume presents essays that emerged from a colloquium on the topic of cosmogony (the creation of the world) among ancient Jews and Chris- tians held at Princeton University in May 2010. -

What the Muses Sang: Theogony 1-115 Jenny Strauss Clay

STRAUSS CLAY, JENNY, What the Muses Sang: "Theogony" 1-115 , Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies, 29:4 (1988:Winter) p.323 What the Muses Sang: Theogony 1-115 Jenny Strauss Clay HE PROEM to the Theogony has often been analyzed both in T terms of its formal structure and in relation to recurrent hym nic conventions;l it has also been interpreted as a fundamental statement of archaic Greek poetics.2 While differing somewhat in its perspective, the present investigation builds on and complements those previous studies. Dedicated to the Muses, the patronesses of poetry, the opening of the Theogony repeatedly describes these divini ties engaged in their characteristic activity, that is, singing. In the course of the proem, the Muses sing four times: once as they descend from Helicon (lines 11-21), twice on Olympus (44-50, 66f), and once as they make their way from their birthplace in Pieria and ascend to Olympus (71-75). In addition, the prologue describes the song the goddesses inspire in their servants, the aoidoi (99-101), as well as the song Hesiod requests that they sing for him, the invocation proper (105-15). My aim here is a simple one: to examine the texts and contexts of each of these songs and to compare them to the song the Muses instruct Hesiod to sing and the one he finally produces. I See, for example, P. Friedlander, "Das Pro6mium von Hesiods Theogonie" (1914), in E. HEITSCH, Hesiod (Darmstadt 1966: hereafter "Heitsch") 277-94; W. Otto, "Hesiodea," in Varia Variorum: Festgabe fUr Karl Reinhardt (Munster 1952) 49-53; P. -

Pre-Philosophical Conceptions of Truth in Ancient Greece

Pre-Philosophical Conceptions of Truth in Ancient Greece https://www.ontology.co/aletheia-prephilosophical.htm Theory and History of Ontology by Raul Corazzon | e-mail: [email protected] PRE-PHILOSOPHICAL CONCEPTS OF TRUTH IN ANCIENT GREECE THE PRE-PHILOSOPHICAL USAGE OF ALETHÉIA HOMER Texts: Studies: "As scholars have often pointed out, the word Aletheia only occurs in the Iliad and the Odyssey in connection with verbs of saying, and its opposite is a lie or deception. Someone always tells the truth to another. Of the seventeen occurrences, (a) this triadic pattern is explicit in all but six, and in those few cases the reference to a hearer is clearly implied. Truth has to do with the reliability of what is said by one person to another. What is not so often pointed out are some quite distinctive features of the Homeric use of Aletheia. This is not the only word Homer uses to mean truth; he has a number of other words which mean 'true', 'genuine', 'accurate', and 'precise' (atrekes, eteos, etetumos, etumos). These words, as adjectives or adverbs, occur freely in the midst of stories and speeches. By contrast, Aletheia occurs almost always as a noun or neuter adjective (once the cognate adverb alethes is used). It is the word Homer uses when he wishes to signify 'the truth'. Furthermore, it is very revealing that the sentence, 'Then verily, child, I will tell you the truth', occurs five times in the Odyssey with but minor variations. (b) It is a high-sounding formula used to introduce a speech. The repetition of lines and formulaic phrases-sometimes, indeed, a number of lines-is a feature of the Homeric style. -

Rejoining Aletheia and Truth: Or Truth Is a Five-Letter Word

Old Dominion Univ. Rejoining Aletheia and Truth: or Truth Is a Five-Letter Word Lawrence J. Hatab EGINNING WITH Being and Time, Heidegger was engaged in thinking the Bword truth (Wahrheit) in terms of the notion of un concealment (aletheia).1 Such thinking stemmed from a two-fold interpretation: (1) an etymological analy sis of the Greek word for truth, stressing the alpha-privative; (2) a phenomenolog ical analysis of the priority of disclosure, which is implicit but unspoken in ordinary conceptions of truth. In regard to the correspondence theory, for example, before a statement can be matched with a state of affairs, "something" must first show itself (the presence of a phenomenon, the meaning of Being in general) in a process of emergence out of concealment. This is a deeper sense of truth that Heidegger came to call the "truth of Being." The notion of emergence expressed as a double-negative (un-concealment) mirrors Heidegger's depiction of the negativity of Being (the Being-Nothing correlation) and his critique of metaphysical foundationalism, which was grounded in various positive states of being. The "destruction" of metaphysics was meant to show how this negative dimension was covered up in the tradition, but also how it could be drawn out by a new reading of the history of metaphysics. In regard to truth, its metaphysical manifestations (representation, correspondence, correctness, certainty) missed the negative background of mystery implied in any and all disclosure, un concealment. At the end of his thinking, Heidegger turned to address this mystery as such, independent of metaphysics or advents of Being (un-concealment), to think that which withdraws in the disclosure of the Being of beings (e.g., the Difference, Ereignis, lethe). -

Parmenides' Theistic Metaphysics

Parmenides’ Theistic Metaphysics BY ©2016 Jeremy C. DeLong Submitted to the graduate degree program in Philosophy and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ________________________________ Chairperson: Tom Tuozzo ________________________________ Eileen Nutting ________________________________ Scott Jenkins ________________________________ John Symons ________________________________ John Younger Date Defended: May 6th, 2016 ii The Dissertation Committee for Jeremy C. DeLong certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: Parmenides’ Theistic Metaphysics ________________________________ Chairperson: Thomas Tuozzo Date Defended: May 6th, 2016 iii Abstract: The primary interpretative challenge for understanding Parmenides’ poem revolves around explaining both the meaning of, and the relationship between, its two primary sections: a) the positively endorsed metaphysical arguments which describe some unified, unchanging, motionless, and eternal “reality” (Aletheia), and b) the ensuing cosmology (Doxa), which incorporates the very principles explicitly denied in Aletheia. I will refer to this problem as the “A-D Paradox.” I advocate resolving this paradoxical relationship by reading Parmenides’ poem as a ring-composition, and incorporating a modified version of Palmer’s modal interpretation of Aletheia. On my interpretation, Parmenides’ thesis in Aletheia is not a counter-intuitive description of how all the world (or its fundamental, genuine entities) must truly be, but rather a radical rethinking of divine nature. Understanding Aletheia in this way, the ensuing “cosmology” (Doxa) can be straightforwardly rejected as an exposition of how traditional, mythopoetic accounts have misled mortals in their understanding of divinity. Not only does this interpretative view provide a resolution to the A-D Paradox, it offers a more holistic account of the poem by making the opening lines of introduction (Proem) integral to understanding Parmenides’ message. -

A Theology of Memory: the Concept of Memory in the Greek Experience of the Divine

A Theology of Memory: The Concept of Memory in the Greek Experience of the Divine Master’s Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Department of Classical Studies Leonard Muellner, Advisor In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For Master’s Degree by Michiel van Veldhuizen May 2012 ABSTRACT A Theology of Memory: The Concept of Memory in the Greek Experience of the Divine A thesis presented to the Department of Classical Studies Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Waltham, Massachusetts By Michiel van Veldhuizen To the ancient Greek mind, memory is not just concerned with remembering events in the past, but also concerns knowledge about the present, and even the future. Through a structural analysis of memory in Greek mythology and philosophy, we may come to discern the particular role memory plays as the facilitator of vertical movement, throwing a bridge between the realms of humans and gods. The concept of memory thus plays a significant role in the Greek experience of the divine, as one of the vertical bridges that relates mortality and divinity. In the theology of Mnemosyne, who is Memory herself and mother of the Muses, memory connects not only to the singer-poet’s religiously efficacious speech of prophetic omniscience, but also to the idea of Truth itself. The domain of memory, then, shapes the way in which humans have access to the divine, the vertical dimension of which is expliticly expressed in the descent-ascent of the ritual passage of initiation. The present study thus lays bare the theology of Memory. -

California Cosmogony Curriculum: the Legacy of James Moffett by Geoffrey Sirc and Thomas Rickert

CALIFONIA COSMOGONY CURRICULUM: THE LEGACY OF JAMES MOFFEtt GEOFFREY SIRC AND THOMAS RICKERT enculturation intermezzo • ENCULTURATION ~ INTERMEZZO • ENCULTURATION, a Journal of Rhetoric, Writing, and Culture, announces the launch of Intermezzo, a series dedicated to publishing long essays – between 20,000 and 80,000 words – that are too long for journal publication, but too short to be a monograph. Intermezzo fills a current gap within scholarly writing by allowing writers to express themselves outside of the constraints of formal academic publishing. Intermezzo asks writers to not only consider a variety of topics from within and without academia, but to be creative in doing so. Authors are encouraged to experiment with form, style, content, and approach in order to break down the barrier between the scholarly and the creative. Authors are also encouraged to contribute to existing conversations and to create new ones. INTERMEZZO essays, published as ebooks, will broadly address topics of academic and general audience interest. Longform or Longreads essays have proliferated in recent years across blogs and online magazine outlets as writers create new spaces for thought. While some scholarly presses have begun to consider the extended essay as part of their overall publishing, scholarly writing, overall, still lacks enough venues for this type of writing. Intermezzo contributes to this nascent movement by providing new spaces for scholarly writing that the academic journal and monograph cannot accommodate. Essays are meant to be provocative, intelligent, and not bound to standards traditionally associated with “academic writing.” While essays may be academic regarding subject matter or audience, they are free to explore the nature of digital essay writing and the various logics associated with such writing - personal, associative, fragmentary, networked, non-linear, visual, and other rhetorical gestures not normally appreciated in traditional, academic publishing. -

Fantasies of Independence and Their Latin American Legacies by Gabriel

Fantasies of Independence and Their Latin American Legacies by Gabriel A Horowitz A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Romance Languages and Literatures - Spanish) in the University of Michigan 2014 Doctoral Committee: Professor Gareth Williams, Chair Professor Frieda Ekotto Associate Professor Katharine M. Jenckes Associate Professor Daniel Noemi-Voionmaa, Northeastern University So twice five miles of fertile ground with walls and towers were girdled round: And there were gardens bright with sinuous rills, Where blossomed many an incense-bearing tree; And here were forests ancient as the hills, Enfolding sunny spots of greenery. But oh! that deep romantic chasm which slanted Down the green hill athwart a cedern cover! A savage place! as holy and enchanted As e’er beneath a waning moon was haunted By woman wailing for her demon lover! –Samuel Taylor Coleridge One must surround nature in order to dominate it: if we go blindly ahead, trying to divine instead of observe, it will escape us completely –José Luz y Caballero La ciencia, como la naturaleza se alimenta de ruinas, y mientras los sistemas nacen y crecen y se marchitan y mueren, ella se levanta lozana y florida sobre sus despojos, y mantiene una juventud eternal –Andrés Bello I pursued nature to her hiding places. Who shall conceive the horrors of my secret toil, as I dabbled among the unhallowed damps of the grave, or tortured the living animal to animate the lifeless clay? –Mary Shelley The enslavement to nature of people today cannot be separated from social progress –Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer © Gabriel A Horowitz 2014 For Cori, Joe, and Lee ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I owe a great debt to my dissertation chair Gareth Williams for his rigor and perseverance in helping me develop as a scholar and as a writer. -

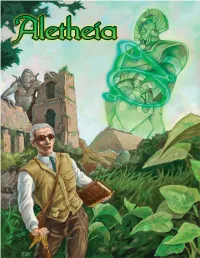

Aletheia (Different Strings) Is Published by Abstract Nova Entertainment LLC, 10633 Bent Tree Dr., Fredericksburg, VA 22407

a l e t h e i a WRITING Werner Hager, Lee Foster, Monica Valentinelli EDITING Anita Hager COVER Storn Cook BLACK & WHITE ART Annelisa Ochoa COLOR ART Jennifer Rodgers CARTOGRAPHY Keith Curtis GRAPHICS Keith Curtis and Edward Wedig LOGO DESIGN Keith Curtis CHARACTER SHEET Edward Wedig Aletheia (Different Strings) is published by Abstract Nova Entertainment LLC, 10633 Bent Tree Dr., Fredericksburg, VA 22407. All text and graphics are © 2007 Abstract Nova Entertainment LLC. All artwork is © 2007 Storn Cook, Annelisa Ochoa, or Jennifer Rodgers. All rights reserved under international law. No part of this book may be reproduced in part or whole, in any form or by any means, except for pur- poses of review, without the express written consent of the copyright holders with the exception of the character sheet and cartography. TABLE of contents INTRODUCTION 4 HISTORY 7 HEPTA SOPHISTAI 4 CHARACTERS 34 MECHANICS 46 ANOMALOUS PHENOMENA 68 REVELATIONS 87 GAMEMASTERING 123 FROM THE HEAVENS 161 INDEX 172 chapter one introduction 3 All religions, arts, and sciences are branches of the same in the universe. By investigating the little mysteries, tree. All these aspirations are directed toward ennobling and discovering the truth behind the unexplainable, man’s life, lifting it from the sphere of mere physical the society hopes to gain a more complete picture of existence and leading the individual towards freedom. reality. – Albert Einstein The society is a small one, numbering only seven. A generous benefactor funds the society and provides each member with whatever he or she might need. With all material concerns and burdens removed, the society members can fully devote themselves to the cientists and philosophers have long search for truth. -

Espiral Negra: Concretude in the Atlantic 25 2

The Object of the Atlantic 8flashpoints The FlashPoints series is devoted to books that consider literature beyond strictly national and disciplinary frameworks and that are distinguished both by their historical grounding and by their theoretical and conceptual strength. Our books engage theory without losing touch with history and work historically without falling into uncritical positivism. FlashPoints aims for a broad audience within the humanities and the social sciences concerned with moments of cultural emer- gence and transformation. In a Benjaminian mode, FlashPoints is interested in how literature contributes to forming new constellations of culture and history and in how such formations function critically and politically in the present. Series titles are available online at http://escholarship.org/uc/flashpoints. series editors: Ali Behdad (Comparative Literature and English, UCLA), Founding Editor; Judith Butler (Rhetoric and Comparative Literature, UC Berkeley), Founding Editor; Michelle Clayton (Hispanic Studies and Comparative Literature, Brown University); Edward Dimendberg (Film and Media Studies, Visual Studies, and European Languages and Studies, UC Irvine), Coordinator; Catherine Gallagher (English, UC Berkeley), Founding Editor; Nouri Gana (Comparative Literature and Near Eastern Languages and Cultures, UCLA); Susan Gillman (Literature, UC Santa Cruz); Jody Greene (Literature, UC Santa Cruz); Richard Terdiman (Literature, UC Santa Cruz) A list of titles in the series begins on p. 273. The Object of the Atlantic Concrete Aesthetics in Cuba, Brazil, and Spain, 1868–1968 Rachel Price northwestern university press ❘ evanston, illinois this book is made possible by a collaborative grant from the andrew w. mellon foundation. Northwestern University Press www.nupress.northwestern.edu Copyright © 2014 by Northwestern University Press. -

Heidegger, Aletheia, and Assertions Erin M

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2009 Heidegger, aletheia, and assertions Erin M. Kraus Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Kraus, Erin M., "Heidegger, aletheia, and assertions" (2009). LSU Master's Theses. 2197. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/2197 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HEIDEGGER, ALETHEIA, AND ASSERTIONS A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The Department of Philosophy and Religious Studies by Erin M. Kraus B.A. Salisbury University, 2006 May 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT……………………………………………………………………………iii CHAPTER 1: THE PRIMORDIAL PHENEMON OF THE WORLD…………………1 1.1: Introduction………………………………………………………………………....1 1.2: Dasein and Its World………………………………………………………………..7 1.3: The Correspondence Theory and Aristotle…………………………………………18 CHAPTER 2: PRIVILEGING THE PRESENT-AT-HAND…………………………...22 2.1: Heidegger’s Critique of Descartes…………………………………………………..22 2.2: Presence-at-Hand and Assertions…………………………………………………...29 -

Etymology Five Examples of Another Truth, from Democritus to Foucault

Etymology Five Examples of Another Truth, From Democritus to Foucault Vincent W.J. van Gerven Oei Ph.D. (European Graduate School, 2011) M.Mus. (Royal Conservatoire, 2007) M.A. (Leiden University, 2005) A thesis presented for the degree of Ph.D. in Modern Thought at the University of Aberdeen. 2016 Summary In lieu of an introduction, this dissertation starts with a short exposé on the paradigm, or the example, which provides the general framework in which the argument will de- velop – namely to the side of more classical modes of deductive or inductive reasoning. Our argument here is that in order to inspect a concept – etumos logos – that has been repressed throughout most of the history of metaphysics, our biggest chance of uncov- ering some of it is to avoid modes of the logos that have been specifically prominent in that history of repression. In the First Example we investigate the predominance of alētheia as philosophically dominant word for truth, while locating in the work of Martin Heidegger a sustained attempt to undermine and recast the precise meaning of that word. It is our claim that even though Heidegger, ever reaching farther back in the history of Western philosophy, up to the first, non-philosophical, poetical attestations of the Ancient Greek language, manages to uncover many subtleties in the meaning and origin of truth as alētheia, he fails to notice that in the epic literature predating the first philosophical works alētheia is in no way the privileged word for truth. By investigating the precise semantics of the contrast between etumos/etētumos/ eteos and alēthēs in the work of Homer and Hesiod, and the slow disappearance of this contrast in Aeschylus and Pindar, we suggest a parallel between on the one hand the disappearance of the former and Heidegger’s insistent neglect of this disappearance.