Read the Full PDF

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Haessly, Katie (2010) British Conservative Women Mps

British Conservative Women MPs and ‘Women’s Issues’ 1950-1979 Katie Haessly, BA MA Thesis submitted to the University of Nottingham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2010 1 Abstract In the period 1950-1979, there were significant changes in legislation relating to women’s issues, specifically employment, marital and guardianship and abortion rights. This thesis explores the impact of Conservative female MPs on these changes as well as the changing roles of women within the party. In addition there is a discussion of the relationships between Conservative women and their colleagues which provides insights into the changes in gender roles which were occurring at this time. Following the introduction the next four chapters focus on the women themselves and the changes in the above mentioned women’s issues during the mid-twentieth century and the impact Conservative women MPs had on them. The changing Conservative attitudes are considered in the context of the wider changes in women’s roles in society in the period. Chapter six explores the relationship between women and men of the Conservative Parliamentary Party, as well as men’s impact on the selected women’s issues. These relationships were crucial to enhancing women’s roles within the party, as it is widely recognised that women would not have been able to attain high positions or affect the issues as they did without help from male colleagues. Finally, the female Labour MPs in the alteration of women’s issues is discussed in Chapter seven. Labour women’s relationships both with their party and with Conservative women are also examined. -

Liberalism, Social Democracy, and Tom Kent Kenneth C

Liberalism, Social Democracy, and Tom Kent Kenneth C. Dewar Journal of Canadian Studies/Revue d'études canadiennes, Volume 53, Number/numéro 1, Winter/hiver 2019, pp. 178-196 (Article) Published by University of Toronto Press For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/719555 Access provided by Mount Saint Vincent University (19 Mar 2019 13:29 GMT) Journal of Canadian Studies • Revue d’études canadiennes Liberalism, Social Democracy, and Tom Kent KENNETH C. DEWAR Abstract: This article argues that the lines separating different modes of thought on the centre-left of the political spectrum—liberalism, social democracy, and socialism, broadly speaking—are permeable, and that they share many features in common. The example of Tom Kent illustrates the argument. A leading adviser to Lester B. Pearson and the Liberal Party from the late 1950s to the early 1970s, Kent argued for expanding social security in a way that had a number of affinities with social democracy. In his paper for the Study Conference on National Problems in 1960, where he set out his philosophy of social security, and in his actions as an adviser to the Pearson government, he supported social assis- tance, universal contributory pensions, and national, comprehensive medical insurance. In close asso- ciation with his philosophy, he also believed that political parties were instruments of policy-making. Keywords: political ideas, Canada, twentieth century, liberalism, social democracy Résumé : Cet article soutient que les lignes séparant les différents modes de pensée du centre gauche de l’éventail politique — libéralisme, social-démocratie et socialisme, généralement parlant — sont perméables et qu’ils partagent de nombreuses caractéristiques. -

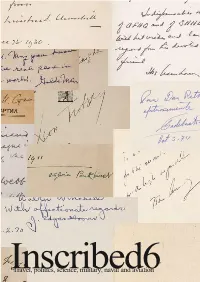

Inscribed 6 (2).Pdf

Inscribed6 CONTENTS 1 1. AVIATION 33 2. MILITARY 59 3. NAVAL 67 4. ROYALTY, POLITICIANS, AND OTHER PUBLIC FIGURES 180 5. SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY 195 6. HIGH LATITUDES, INCLUDING THE POLES 206 7. MOUNTAINEERING 211 8. SPACE EXPLORATION 214 9. GENERAL TRAVEL SECTION 1. AVIATION including books from the libraries of Douglas Bader and “Laddie” Lucas. 1. [AITKEN (Group Captain Sir Max)]. LARIOS (Captain José, Duke of Lerma). Combat over Spain. Memoirs of a Nationalist Fighter Pilot 1936–1939. Portrait frontispiece, illustrations. First edition. 8vo., cloth, pictorial dust jacket. London, Neville Spearman. nd (1966). £80 A presentation copy, inscribed on the half title page ‘To Group Captain Sir Max AitkenDFC. DSO. Let us pray that the high ideals we fought for, with such fervent enthusiasm and sacrifice, may never be allowed to perish or be forgotten. With my warmest regards. Pepito Lerma. May 1968’. From the dust jacket: ‘“Combat over Spain” is one of the few first-hand accounts of the Spanish Civil War, and is the only one published in England to be written from the Nationalist point of view’. Lerma was a bomber and fighter pilot for the duration of the war, flying 278 missions. Aitken, the son of Lord Beaverbrook, joined the RAFVR in 1935, and flew Blenheims and Hurricanes, shooting down 14 enemy aircraft. Dust jacket just creased at the head and tail of the spine. A formidable Vic formation – Bader, Deere, Malan. 2. [BADER (Group Captain Douglas)]. DEERE (Group Captain Alan C.) DOWDING Air Chief Marshal, Lord), foreword. Nine Lives. Portrait frontispiece, illustrations. First edition. -

Lewis Minkin and the Party–Unions Link

ITLP_C11.QXD 18/8/03 10:02 am Page 166 11 Lewis Minkin and the party–unions link Eric Shaw ‘For over 80 years’, Minkin declares in his magisterial survey The Contentious Alliance (1991: xii), the Labour Party–trade unions link ‘has shaped the structure and, in various ways, the character of the British Left’.His core proposition can be encapsulated simply: trade union ‘restraint has been the central characteristic’ of the link (1991: 26). This constitutes a frontal challenge to received wisdom – end- lessly repeated, recycled and amplified by Britain’s media – that, until the ‘mod- ernisation’ of the party, initiated by Neil Kinnock and accelerated by Tony Blair, the unions ran the party. So ingrained is this wisdom in British political culture that no discussion of party–unions relations in the media can endure for long without some reference to the days when ‘the union barons controlled the party’.This view, Minkin holds, is a gross over-simplification and, to a degree, downright mislead- ing. The relationship is infinitely more subtle and complex, and far more balanced than the conventional view allows. The task Minkin sets himself in The Contentious Alliance is twofold: on the one hand to explain why and how he reached that con- clusion; and, on the other – the core of the book – to lay bare the inner dynamics of the party–unions connection. What is most distinctive and enduring about Minkin’s work? In what ways has it most contributed to our understanding of the labour movement? Does it still offer insights for scholars of Labour politics? In the first section of this paper, I examine how Minkin contests the premisses underpinning the orthodox thesis of trade union ‘baronial power’; in the second, I analyse the ‘sociological’frame of ref- erence he devised as an analytical tool to uncover the roots and essential proper- ties of the party–unions connection; in the third section, I address the question of the relevance of Minkin today. -

Discussing What Prime Ministers Are For

Discussing what Prime Ministers are for PETER HENNESSY New Labour has a lot to answer for on this front. They On 13 October 2014, Lord Hennessy of Nympsfield FBA, had seen what the press was doing to John Major from Attlee Professor of Contemporary British History at Queen Black Wednesday onwards – relentless attacks on him, Mary, University of London, delivered the first British which bothered him deeply.1 And they were determined Academy Lecture in Politics and Government, on ‘What that this wouldn’t happen to them. So they went into are Prime Ministers for?’ A video recording of the lecture the business of creating permanent rebuttal capabilities. and an article published in the Journal of the British Academy If somebody said something offensive about the can be found via www.britishacademy.ac.uk/events/2014/ Government on the Today programme, they would make every effort to put it right by the World at One. They went The following article contains edited extracts from the into this kind of mania of permanent rebuttal, which question and answer session that followed the lecture. means that you don’t have time to reflect before reacting to events. It’s arguable now that, if the Government doesn’t Do we expect Prime Ministers to do too much? react to events immediately, other people’s versions of breaking stories (circulating through social media etc.) I think it was 1977 when the Procedure Committee in will make the pace, and it won’t be able to get back on the House of Commons wanted the Prime Minister to be top of an issue. -

Her Majesty's Government

• tl HER MAJESTY'S GOVERNMENT MEMBERS OF THE CABINET (FORMED BY RIGHT HON. MARGARET THATCHER, 24:P, SEPTEMBER 1981) E— CRETARY OF STATE FOR THE HOME DEPARTMENT—TheRt. HOD. William Whitelaw, CH, MC, Ise .1441u) CHANCELLOR—The Rt. Hon. The Lord Hailsham of Saint Marylebone, CH OCRETARY OF STATE FOR FOREIGN AND CommoNwEALTH AFFAnts—The Rt. Hon. The Lord Carrington, KCMG, MC OANCELLOR OF THE EXCHEQUER—The Rt. Hon. Sir Geoffrey Howe, QC, MP tiekRETARY OF STATE FOR EDUCATION AND SCIENCE—The Rt. Hon. Sir Keith Joseph, Bt, MP yitORD PRESIDENT OF THE COUNCIL AND LEADER OF THE HOUSE OFCommoNs—The Rt. HOD. Francis Pym, MC, MP RETARY OF STATE FOR NORTHERN IRELAND—TheRt. HOD. James PriOr, MP rECRETARY OF STATE FOR DEFENCE—The Rt. HOD. John Nott, MP ',MINISTER OF AGRICULTURE, FISHERIES ANDFooD—The Rt. Hon. Peter Walker, MBE, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR THE ENVIRONMENT—The Rt. Hon. Michael Heseltine, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR ScoTLAND—The Rt. Hon. George Younger, T.D. MP PCRETARY OF STATE FOR WALEs—The Rt. Hon. Nicholas Edwards, MP PRIVY SEAL—The Rt. Hon. Humphrey Atkins, MP ,ORDCRETARY OF STATE FOR INDUSTRY—The Rt. Hon. Patrick Jenkin, MP tolIrRETARY OF STATE FOR SOCIAL SERVICES—The Rt. Hon. Norman Fowler, MP oncRETARY OF STATE FOR TRADE—The Rt. Hon. John Biffen, IvfP logkRETARY OF STATE FOR ENERGY—The Rt. HOD. Nigel Lawson, MP pitCRETARY OF STATE FOR TRANSPORT—The Rt. Hon. David Howell, MP "oef-DEF SECRETARY TO THE TREASURY—TheRt. Hon. Leon Brittan, QC, MP priANCELLOR OF THE DUCHY OF LANCASTER, AND LEADER OF THE HOUSE OF LoRDs—The Rt. -

The Attlee Governments

Vic07 10/15/03 2:11 PM Page 159 Chapter 7 The Attlee governments The election of a majority Labour government in 1945 generated great excitement on the left. Hugh Dalton described how ‘That first sensa- tion, tingling and triumphant, was of a new society to be built. There was exhilaration among us, joy and hope, determination and confi- dence. We felt exalted, dedication, walking on air, walking with destiny.’1 Dalton followed this by aiding Herbert Morrison in an attempt to replace Attlee as leader of the PLP.2 This was foiled by the bulky protection of Bevin, outraged at their plotting and disloyalty. Bevin apparently hated Morrison, and thought of him as ‘a scheming little bastard’.3 Certainly he thought Morrison’s conduct in the past had been ‘devious and unreliable’.4 It was to be particularly irksome for Bevin that it was Morrison who eventually replaced him as Foreign Secretary in 1951. The Attlee government not only generated great excitement on the left at the time, but since has also attracted more attention from academics than any other period of Labour history. Foreign policy is a case in point. The foreign policy of the Attlee government is attractive to study because it spans so many politically and historically significant issues. To start with, this period was unique in that it was the first time that there was a majority Labour government in British political history, with a clear mandate and programme of reform. Whereas the two minority Labour governments of the inter-war period had had to rely on support from the Liberals to pass legislation, this time Labour had power as well as office. -

Apprentice Strikes in Twentieth Century UK Engineering and Shipbuilding*

Apprentice strikes in twentieth century UK engineering and shipbuilding* Paul Ryan Management Centre King’s College London November 2004 * Earlier versions of this paper were presented to the International Conference on the European History of Vocational Education and Training, University of Florence, the ESRC Seminar on Historical Developments, Aims and Values of VET, University of Westminster, and the annual conference of the British Universities Industrial Relations Association. I would like to thank Alan McKinlay and David Lyddon for their generous assistance, and Lucy Delap, Alan MacFarlane, Brian Peat, David Raffe, Alistair Reid and Keith Snell for comments and suggestions; the Engineering Employers’ Federation and the Department of Education and Skills for access to unpublished information; the staff of the Modern Records Centre, Warwick, the Mitchell Library, Glasgow, the Caird Library, Greenwich, and the Public Record Office, Kew, for assistance with archive materials; and the Nuffield Foundation and King’s College, Cambridge for financial support. 2 Abstract Between 1910 and 1970, apprentices in the engineering and shipbuilding industries launched nine strike movements, concentrated in Scotland and Lancashire. On average, the disputes lasted for more than five weeks, drawing in more than 15,000 young people for nearly two weeks apiece. Although the disputes were in essence unofficial, they complemented sector-wide negotiations by union officials. Two interpretations are considered: a political-social-cultural one, emphasising political motivation and youth socialisation, and an economics-industrial relations one, emphasising collective action and conflicting economic interests. Both interpretations prove relevant, with qualified priority to the economics-IR one. The apprentices’ actions influenced economic outcomes, including pay structures and training incentives, and thereby contributed to the decline of apprenticeship. -

'The Left's Views on Israel: from the Establishment of the Jewish State To

‘The Left’s Views on Israel: From the establishment of the Jewish state to the intifada’ Thesis submitted by June Edmunds for PhD examination at the London School of Economics and Political Science 1 UMI Number: U615796 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615796 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 F 7377 POLITI 58^S8i ABSTRACT The British left has confronted a dilemma in forming its attitude towards Israel in the postwar period. The establishment of the Jewish state seemed to force people on the left to choose between competing nationalisms - Israeli, Arab and later, Palestinian. Over time, a number of key developments sharpened the dilemma. My central focus is the evolution of thinking about Israel and the Middle East in the British Labour Party. I examine four critical periods: the creation of Israel in 1948; the Suez war in 1956; the Arab-Israeli war of 1967 and the 1980s, covering mainly the Israeli invasion of Lebanon but also the intifada. In each case, entrenched attitudes were called into question and longer-term shifts were triggered in the aftermath. -

Carter Networks Use British Courts Against Callaghan

Click here for Full Issue of EIR Volume 4, Number 6, February 8, 1977 Equal Employee Representation: The Key To Industrial Expansion The following are extracts from the Minority Report of ments to any form of board representation. the Bullock Committee. which were prepared by Mr. N. Our recommendation, subject to the creation or P. Biggs. Sir Jack Callard and Mr. Barrie Heath. The existence of a suitable substructure, is that if there is to Minority Report. in contrast with the Majority view of be employee representation at board level, it should be the Bullock Committee. calls for worker representation on supervisory boards. on supervisory boards. based on the West German We propose that a supervisory board, where adopted, model. which would leave the existing board structure in should consist of: one-third elected by employees; one British industry virtually intact. Further. the report en third elected by the shareholders; one-third independent visages the formation of such supervisory boards. to members. Included in the one third employee elected re ha ve no formal links with the trade union apparatus. only presentatives should be at least one member from the following a number of years experience with work coun shop floor payroll, one from the salaried staff employees, cils within each company. and one from management. If a supervisory board is to serve a useful purpose. it We present this minority report in the confidence that should not be a watchdog without teeth. It should exer our views will have the support of large sections of the in cise general supervision over the conduct of the compa dustrial community. -

Conservative Party Leaders and Officials Since 1975

BRIEFING PAPER Number 07154, 6 February 2020 Conservative Party and Compiled by officials since 1975 Sarah Dobson This List notes Conservative Party leaders and officials since 1975. Further reading Conservative Party website Conservative Party structure and organisation [pdf] Constitution of the Conservative Party: includes leadership election rules and procedures for selecting candidates. Oliver Letwin, Hearts and Minds: The Battle for the Conservative Party from Thatcher to the Present, Biteback, 2017 Tim Bale, The Conservative Party: From Thatcher to Cameron, Polity Press, 2016 Robert Blake, The Conservative Party from Peel to Major, Faber & Faber, 2011 Leadership elections The Commons Library briefing Leadership Elections: Conservative Party, 11 July 2016, looks at the current and previous rules for the election of the leader of the Conservative Party. Current state of the parties The current composition of the House of Commons and links to the websites of all the parties represented in the Commons can be found on the Parliament website: current state of the parties. www.parliament.uk/commons-library | intranet.parliament.uk/commons-library | [email protected] | @commonslibrary Conservative Party leaders and officials since 1975 Leader start end Margaret Thatcher Feb 1975 Nov 1990 John Major Nov 1990 Jun 1997 William Hague Jun 1997 Sep 2001 Iain Duncan Smith Sep 2001 Nov 2003 Michael Howard Nov 2003 Dec 2005 David Cameron Dec 2005 Jul 2016 Theresa May Jul 2016 Jun 2019 Boris Johnson Jul 2019 present Deputy Leader # start end William Whitelaw Feb 1975 Aug 1991 Peter Lilley Jun 1998 Jun 1999 Michael Ancram Sep 2001 Dec 2005 George Osborne * Dec 2005 July 2016 William Hague * Dec 2009 May 2015 # There has not always been a deputy leader and it is often an official title of a senior Conservative politician. -

Holders of Ministerial Office in the Conservative Governments 1979-1997

Holders of Ministerial Office in the Conservative Governments 1979-1997 Parliamentary Information List Standard Note: SN/PC/04657 Last updated: 11 March 2008 Author: Department of Information Services All efforts have been made to ensure the accuracy of this data. Nevertheless the complexity of Ministerial appointments, changes in the machinery of government and the very large number of Ministerial changes between 1979 and 1997 mean that there may be some omissions from this list. Where an individual was a Minister at the time of the May 1997 general election the end of his/her term of office has been given as 2 May. Finally, where possible the exact dates of service have been given although when this information was unavailable only the month is given. The Parliamentary Information List series covers various topics relating to Parliament; they include Bills, Committees, Constitution, Debates, Divisions, The House of Commons, Parliament and procedure. Also available: Research papers – impartial briefings on major bills and other topics of public and parliamentary concern, available as printed documents and on the Intranet and Internet. Standard notes – a selection of less formal briefings, often produced in response to frequently asked questions, are accessible via the Internet. Guides to Parliament – The House of Commons Information Office answers enquiries on the work, history and membership of the House of Commons. It also produces a range of publications about the House which are available for free in hard copy on request Education web site – a web site for children and schools with information and activities about Parliament. Any comments or corrections to the lists would be gratefully received and should be sent to: Parliamentary Information Lists Editor, Parliament & Constitution Centre, House of Commons, London SW1A OAA.