Forced Departures and Fragmented Realities in Palestinian Memoirs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

West Bank Barrier Route Projections July 2009

United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs LEBANON SYRIA West Bank Barrier Route Projections July 2009 West Bank Gaza Strip JORDAN Barta'a ISRAEL ¥ EGYPT Area Affected r The Barrier’s total length is 709 km, more than e v i twice the length of the 1949 Armistice Line R n (Green Line) between the West Bank and Israel. W e s t B a n k a d r o The total area located between the Barrier J and the Green Line is 9.5 % of the West Bank, Qalqilya including East Jerusalem and No Man's Land. Qedumim Finger When completed, approximately 15% of the Barrier will be constructed on the Green Line or in Israel with 85 % inside the West Bank. Biddya Area Populations Affected Ari’el Finger If the Barrier is completed based on the current route: Az Zawiya Approximately 35,000 Palestinians holding Enclave West Bank ID cards in 34 communities will be located between the Barrier and the Green Line. The majority of Palestinians with East Kafr Aqab Jerusalem ID cards will reside between the Barrier and the Green Line. However, Bir Nabala Enclave Biddu Palestinian communities inside the current Area Shu'fat Camp municipal boundary, Kafr Aqab and Shu'fat No Man's Land Camp, are separated from East Jerusalem by the Barrier. Ma’ale Green Line Adumim Settlement Jerusalem Bloc Approximately 125,000 Palestinians will be surrounded by the Barrier on three sides. These comprise 28 communities; the Biddya and Biddu areas, and the city of Qalqilya. ISRAEL Approximately 26,000 Palestinians in 8 Gush a communities in the Az Zawiya and Bir Nabala Etzion e Enclaves will be surrounded on four sides Settlement S Bloc by the Barrier, with a tunnel or road d connection to the rest of the West Bank. -

Terminals, Agricultural Crossings and Gates

Terminals, Agricultural Crossings and Gates Umm Dar Terminals ’AkkabaDhaher al ’Abed Zabda Agricultural Gate (gap in the Wall) Controlled access through the Wall has been promised by the GOI to Ya’bad Wall (being finalised or complete) Masqufet al Hajj Mas’ud enable movement between Israel and the West Bank for Palestinian West Bank boundary/Green Line (estimate) Qaffin Imreiha populations who are either trapped in enclaves or isolated from their Road network agricultural lands. Palestinian Locality Hermesh Israeli Settlement Nazlat ’Isa An Nazla al Wusta According to Israel's State Attorney's office, five controlled crossings or NOTE: Agricultural Gate locations have been Baqa ash Sharqiya collected from field visits by OCHA staff and An Nazla ash Sharqiya terminals similar to the Erez terminal in northern Gaza will be built along information partners. The Wall trajectory is based on satellite imagery and field visits. An Nazla al Gharbiya the Wall. The Government of Israel recently decided that the Israeli Airport Authority will plan and operate the terminals. One of the main terminals between Israel and the West Bank appears to be being built Zeita Seida near Taibeh, 75 acres (300 dunums)35 in a part of Tulkarm City 36 Kafr Ra’i considered area A. ’Attil ’Illar The remaining terminals/control points are designated for areas near Jenin, Atarot north of Jerusalem, north of the Gush Etzion and near Deir al Ghusun Tarkumiyeh settlement bloc. Al Jarushiya Bal’a Agricultural Crossings and Gates Iktaba Al ’Attara The State Attorney's Office has stated that 26 agricultural gates will be TulkarmNur Shams Camp established along the length of the Wall to allow Palestinian farmers who Kafr Rumman have land west of the Wall, to cross. -

Nablus Governorate

'Ajja 'Anza Sanur Sir Deir al Ghusun ARAB STUDIES SOCIETY Land Suitability for Rangeland - Nablus Governorate Meithalun 'Aqqaba Land Research Center Al Jarushiya This study is implemented by: Tayasir Land RSesHeaUrcWh CEeInKteAr - LRC Sa Nur Evacuated Al Judeida Bal'a Siris Funded by: Iktaba Al 'Attara Al FandaqumiyaJaba' The Italian Cooperation Tubas District Camp Tulkarm Silat adh Dhahr Maskiyyot Administrated by: January 2010 TulkarmDhinnaba Homesh Evacuated United Nations Development Program UNDP / P'APnPabta Bizzariya GIS & Mapping Unit WWW.LRCJ.ORG Burqa Supervised by: Kafr al Labad Yasid Palestinian Ministry of Agriculture Beit Imrin El Far'a Camp Ramin Far'un'Izbat Shufa Avnei Hefetz Enav Tammun Jenin Wadi al Far'a Shufa Sabastiya Talluza Tulkarm Tubas Beit Lid Shavei Shomron Al Badhan Qalqiliya Nablus Ya'arit Deir Sharaf Al 'Aqrabaniya Ar Ras 'Asira ash Shamaliya Roi Salfit Zawata SalitKafr Sur An Nassariya Beqaot Qusin Beit Iba Elon Moreh Jericho Ramallah Kedumim Zefon Beit Wazan Kafr JammalKafr Zibad Giv'at HaMerkaziz 'Azmut Kafr 'Abbush Kafr Qaddum Nablus 'Askar Camp Deir al Hatab Jerusalem Kedumim Sarra Salim Hajja Jit Balata Camp Bethlehem Jayyus Tell Zufin Bracha Hamra Qalqiliya Immatin Kafr QallilRujeib Beit Dajan Hebron Burin 'Asira al Qibliya 'Azzun Karne Shomron Beit Furik Alfei Menashe Ginnot ShomeronNeve Oramin Yizhar Itamar (including Itamar1,2,3,4) Habla Ma'ale Shamron Immanuel 'Awarta Mekhora Al Jiftlik 'Urif East Yizhar , Roads, Caravans, & Infrastructure Kafr Thulth Nofim Yakir Huwwara 'Einabus Beita Zamarot -

The Political Economy of the Second Palestinian Intifada Through the Lens of Dependency Theory and World Systems Analysis

The Political Economy of the Second Palestinian Intifada through the Lens of Dependency Theory and World Systems Analysis By David Borzykowski A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba In partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Department of Political Studies University of Manitoba Winnipeg Copyright © 2010 by David Borzykowski 1 Abstract In the midst of the chaos and the violence of civil-ethnic conflict, there is often little attention paid to the economic consequences which endure long past the moment of crisis. In conflicts that end in situations of prolonged occupation of one national group over another, complex and enduring dependencies tend to develop between occupier and occupied. Since the Israeli occupation of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip in 1967, the Palestinian economy has grown highly dependent upon the Israeli economy and has developed within the confines of Israeli military power. When the second Palestinian Intifada (uprising) broke out in September 2000, the Palestinian economy suffered even more. This paper discusses the Palestinian economy through the framework of dependency theory and world systems analysis. Both theories are used in order to explain the complex relationship between Israel and the Palestinians and the relationship of dependence that has been perpetuated by Israel since the signing of the Oslo Agreement in 1993. i Acknowledgements I would like to thank my advisor Dr. Tami Jacoby for all of her help and guidance over the years. I would also like to thank my parents, Brenda and Abe, and my brother and sister-in-law, Bryan and Lainie, for all the continued support and for always being there for me. -

Palestinian Economy and the Prospects for Its Recovery

40462 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized .UMBER $ECEMBER %CONOMIC-ONITORING2EPORTTOTHE!D(OC,IAISON#OMMITTEE ANDTHE0ROSPECTSFORITS2ECOVERY 4HE0ALESTINIAN%CONOMY 7EST"ANKAND'AZA 4HE7ORLD"ANK Contents FOREWORD – THE CONTEXT FOR THIS REPORT…………………………….……….i 1 – SUMMARY ASSESSMENT AND RECOMMENDATIONS………………………………1 I – THE NEED FOR RAPID ECONOMIC GROWTH…………………………………….1 II – GROWTH IN 2005 – ENCOURAGING BUT INCONCLUSIVE………………………..1 III – CREATING THE PRECONDITIONS FOR ECONOMIC RECOVERY: A PROGRESS REPORT………………………………………………..………….………….....2 IV – NEXT STEPS……………………………………………………………………5 2 – THE STATE OF THE PALESTINIAN ECONOMY: JANUARY THROUGH SEPTEMBER 2005……………………………………………6 I – OVERVIEW............................................................................................................................6 II – ECONOMIC OUTPUT…………………………………………………………….6 III – FISCAL AND FINANCIAL DEVELOPMENTS………………………………………7 IV – LABOR MARKET TRENDS……………………………………………………….9 3 – ECONOMIC RECOVERY: PRECONDITIONS AND PROSPECTS……………………10 I – MOVEMENT AND ACCESS………………………………………………………10 II – PALESTINIAN GOVERNANCE…………………………………………………..16 III – GROWTH PROSPECTS AND THE ROLE OF THE DONORS……………………….22 MAPS – GAZA, WEST BANK…………………………………………………………..24 ANNEX 1 – ECONOMIC SCENARIOS………………………………………………….26 ANNEX 2 – INDICATORS OF ECONOMIC REVIVAL…………………………………..29 ANNEX 3 – “TURNING THE CORNER” .……………………………………………..35 ANNEX 4 – AGREEMENT ON MOVEMENT AND ACCESS…………………………….39 ENDNOTES………………...………………………………………………………...44 -

Environmental Profile for the West Bank Volume 8: Tulkarm District

Environmental Profile for The West Bank Volume 8: Tulkarm District Applied Research Institute - Jerusalem 1996 Table of Contents •= Project Team •= Acknowledgment •= List of Tables •= List of Figures & Photographs •= List of Acronyms & Abbreviation •= Units of Measurement •= Introduction •= PART ONE: General Features of Tulkarm District o Chapter One: Location and Landuse o Chapter Two: Topography and Climate o Chapter Three: Socio-economic Characteristics o Chapter Four: Geology and Soil o Chapter Five: Water Resources o Chapter Six: Agriculture o Chapter Seven: Historical and Archeological Sites •= PART TWO: Environmental Concerns in Tulkarm District o Chapter Eight: Wastewater o Chapter Nine: Solid Waste o Chapter Ten: Air and Noise Pollution •= References •= Appendices o Appendix 1 o Appendix 2 o Appendix 3 Project Team Dr. Jad Isaac Violet Qumsieh Project Leader Project Coordinator Bassam Sha'lan Tulkarm Profile Coordinator Contributors to this volume Maher Owewi M.Sc., Remote Sensing Nader Hrimat M.Sc., Plant Production Walid Sabbah M.Sc., Hydrogeology Nizar Quttosh B.Sc., Biology Deema El Hodali B.Sc., Chemistry Mohammad Abu Amrieh B.Sc.,Agricultural Engineering Faten Al-Juneidi B.Sc., Soil and Irrigation Akram Halayka B.Sc., Geology Roubina Bassous B.Sc., Biology Faten Neiroukh B.Sc., Plant Protection Osama Sleibi B.Sc.,Chemical Engineering Safinaz Bader B.Sc., Soil and Irrigation Nadia Al-Dajani B.Sc., Biology Technical Support Team Leonardo Hosh M.Sc.,International Agricultural Development Isam Ishaq M.Sc., Communication Hanna Maoh B.Sc., Physics Issa Zboun GIS Technician Jamil Shalaldeh GIS Technician Fuad Isaac GIS Technician Thamin Hijawi B.Sc., Agricultural Engineering Shadi Hannuneh GIS Technician Maurice Nur GIS, Map Analysis Nisreen Mansour Secretary Acknowledgment The Applied Research Institute - Jerusalem (ARIJ) would like to thank the Federal Government of Austria, Department of Development Cooperation for their funding of this project through the Society for Austro-Arab Relations (SAAR). -

Silently Displaced in the West Bank

Ecumenical Accompaniment Programme in Palestine & Israel (EAPPI) SILENTLY DISPLACED IN THE WEST BANK 1 2 The Separation Wall in Abu Dis, close to Cliff Hotel in Jerusalem. 3 The Ecumenical Accompaniment Programme in Palestine and Israel (EAPPI) seeks to support local and international efforts to end the Israeli occupation based on principles of international humanitarian and human rights law. Responding to a call from the Heads of Churches in Jerusalem to stand in solidarity with the churches and people in Palestine, the World Council of Churches launched the EAPPI in 2002. Since then, over 500 Ecumenical Accompaniers (EAs) from 16 countries have volunteered for three-month periods. EAs monitor and report violations of human rights and international humanitarian law, support acts of non-violent resistance alongside local Christian and Muslim Palestinians and Israeli peace activists, offer protection through non-violent presence, engage in public policy advocacy and, in general, stand in solidarity with the churches and all those struggling against the occupation. Ecumenical Accompaniment Programme in Palestine and Israel (EAPPI) www.eappi.org The EAPPI is a World Council of Churches programme Published by: EAPPI Editor: Matilda Svensson Photographer: Mats Svensson Printer: Emerezian Est. [email protected] ISBN 978-2-8254-1534-4 June 2009 4 SILENTLY DISPLACED IN THE WEST BANK The Ecumenical Accompaniment Programme in Palestine & Israel (EAPPI) 5 FOREWORD by Manuel Quintero EAPPI international coordinator Armed conflicts or natural disasters force them to abandon their homes, grasping at survival. They do not cross state boundaries, but are displaced to other areas of the national territory as they seek minimal protection and support. -

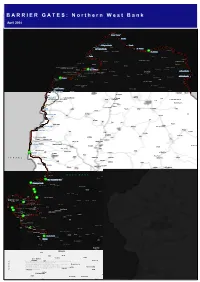

BARRIER GATES: Northern West Bank

West Bank Barrier Gate Summary 7 March - 23 April 2004 Gate Code Governorate/ Gate currently used Special Case Name/Location Gate Type Remarks (see map) Location by Palestinians (see footnote) 1 Jalbun South J1 Military This gate is only open and used by military personnel. Jenin No 2 Jalbun North J2 Military This gate is only open and used by military personnel. Jenin No J3 This gate constitutes a checkpoint with restricted access to Israel proper and functions also as commercial 3 Al Jalama Checkpoint Jenin Yes back-to-back. Official opening hours are 7:00-19:00. 4 Al Yamun J4 Military This gate is only open and used by military personnel. Jenin No 5 Ti 'nnik J5 Military This gate is only open and used by military personnel. Jenin No 6 Zabuba J6 Military This gate is only open and used by military personnel. Jenin No This gate is the entrance to the Jenin DCL office and military base. Palestinians are allowed to use this gate 7 Salem Military Jenin No J7 to visit the DCL office. 8 At Tayba North J8 Agriculture Gate is reported to be open seasonally (October) for access to olive groves. Jenin No 9 At Tayba South J9 Military This gate is only open and used by military personnel. Jenin No 10 Anin J10 Agricultural Gate is reported to be open seasonally (October) for access to olive groves. Jenin No 11 Um al Rihan J11 Checkpoint/Road This gate is open to green permit holders. Official opening hours are 6:00-22:00. -

Persons in Household Households Ges, Total Ersons VOLUME 1

VOLUME 1 TABLE 2 HOUSEHOLDS AND PERSONS, BY RESIDENCE, SEX, AGE AND ORIGIN FROM ISRAEL TERRITORY AND BY LOCALITY West Bank Persons by Age groups Total Persons Persons in Institutions Persons in Household Households Thereof: Thereof: Thereof: Thereof: Locality and Sex Originating Origin at ing Originating Originating 0‐14 15‐29 30‐44 45‐64 65+ Not known Total Total Total Total from Israel from Israel from Israel from Israel Territory Terri to ry Territory Territory Hebron District/Urban Settlements Hebron M 10,747 4,056 2,455 1,526 1,055 95 1,403 19,934 22 139 1,381 19,795 F 9,050 4,151 2,625 1,677 814 58 1,405 18,375 28 79 1,377 18,296 Total 19,797 8,207 5,080 3,203 1,869 153 2,808 38,309 50 218 2,758 38,091 514 7,430 Large Villages Halhul M 1,633 568 344 352 202 13 135 3,112 135 3,112 F 1,404 595 484 283 150 13 153 2,929 153 2,929 Total 3,037 1,163 828 635 352 26 288 6,041 288 6,041 53 1,177 Yatta M 2,013 594 486 348 252 13 51 3,706 51 3,706 F 1,715 757 593 323 174 13 56 3,575 56 3,575 Total 3,728 1,351 1,079 671 426 26 107 7,281 107 7,281 14 1,522 Large Villages, Total M 3,646 1,162 830 700 454 26 186 6,818 186 6,818 F 3,119 1,352 1,077 606 324 26 209 6,504 209 6,504 Total 6,765 2,514 1,907 1,306 778 52 395 13,322 395 13,322 67 2,699 Small Villages Surif M 791 242 195 161 113 4 135 1,506 135 1,506 F 757 290 263 119 59 4 141 1,492 141 1,492 Total 1,548 532 458 280 172 8 276 2,998 276 2,998 51 611 Beit Ummar M 679 296 178 118 97 3 35 1,371 35 1,371 F 594 310 185 113 56 1 31 1,259 31 1,259 Total 1,273 606 363 231 153 4 66 2,630 66 2,630 16 515 Hubeileh M 113 36 17 21 16 160 203 160 203 F 102 34 23 25 5 149 189 149 189 Total 215 70 40 46 21 309 392 309 392 54 70 Kh. -

An Update on Palestinian Movement, Access and Trade in the West Bank and Gaza

World Bank Technical Team Report, August 15, 2006 40461 An Update on Palestinian Movement, Access and Trade in the West Bank and Gaza Summary Public Disclosure Authorized Background This paper provides an updated assessment of movement and access for goods and people in WBG1, which was initiated by the World Bank after the December 2004 Ad Hoc Liaison Committee Meeting when all parties (including the Government of Israel and the Palestinian Authority) agreed that Palestinian economic revival was essential, that it required a major dismantling of today’s closure regime and that closure needed to be addressed from several perspectives at once. In today’s environment of confrontation and heightened risk, movement and access controls have increased and earlier relaxations have been reversed. However, the relationship between Palestinian economic revival and stability and Israeli security remain unarguable and of fundamental importance to both societies’ well-being. Recent initiatives by US-security advisor General Dayton to significantly enhance the security of the Karni crossing between Gaza and Israel in order to ensure an efficient and predicable corridor for trade recognizes this relationship. Public Disclosure Authorized Movement of goods Between Gaza and Israel Growth prospects for the West Bank and Gaza depend critically on its openness to trade. Prior to the Intifada, the flow of cargo into and out of Gaza was largely determined by market demand, with most cargo moving in convoys or through the (then) relatively simple Erez crossing. Today, all cargo flows between Israel and Gaza must be channeled through the Karni crossing point. From a low base of only 43 export trucks per day in the six months prior to the Israeli disengagement from Gaza, actual daily export numbers through mid-June 2006 have fallen to less than 25 trucks a day. -

Weekly Report on Israeli Human Rights Violations in the Occupied Palestinian Territory (26 May – 01 June 2011)

search... Thursday, 02 June 2011 HOME ABOUT US PUBLICATIONS NEWS FACTS / STATS IN FOCUS LINKS Home PUBLICATIONS Reports Weekly Reports Weekly Report On Israeli Human Rights Violations in the Occupied Palestinian Territory (26 May – 01 June 2011) New Weekly Report On Israeli Human Rights Violations in the Occupied Palestinian Territory (26 May – 01 June 2011) Thursday, 02 June 2011 00:00 Israeli forces force a Palestinian civilian to demolish his house in Wad al-Jouz neighborhood in occupied East Jerusalem Israeli Occupation Forces (IOF) Continue Systematic Attacks against Palestinian Civilians and Property in the Occupied Palestinian Territory (OPT) <!--[if !supportLists]-->• <!--[endif]-->A Palestinian child was wounded in Iraq Bourin village, south of Nablus. <!--[if !supportLists]-->• <!--[endif]-->IOF continued to use force against peaceful protests in the West Bank. <!--[if !supportLists]-->- <!--[endif]-->A Palestinian demonstrator was wounded in Bil'ein, west of Ramallah. <!--[if !supportLists]-->- <!--[endif]-->IOF arrested 15 demonstrators, including a child. <!--[if !supportLists]-->- <!--[endif]-->The arrested persons include 7 Palestinians and 8 international human rights defenders. <!--[if !supportLists]-->• <!--[endif]-->IOF conducted 47 incursions into Palestinian communities in the West Bank and one limited incursion into the central Gaza Strip. <!--[if !supportLists]-->- <!--[endif]-->IOF arrested 29 Palestinian civilians, including 4 children and 2 women. <!--[if !supportLists]-->- <!--[endif]-->IOF launched a wide scale campaign against the Islamic Jihad in Jenin and closed 2 charitable associations. <!--[if !supportLists]-->• <!--[endif]-->IOF continued settlement activities and Israeli settlers continued their attacks in the West Bank. <!--[if !supportLists]-->- <!--[endif]-->IOF demolished 8 artisan wells in Jenin and bulldozed a shop of construction materials in Qalqilya. -

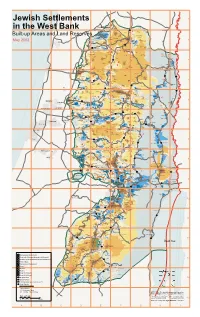

Jewish Settlements in the West Bank

1 Jewish Settlements Zububa Ti'nnik Rummana Umm Al-Fahm Al-Jalama Arabbuna in the West Bank At-Tayba 'Anin Silat Al-Harithiya 60 Arrana Faqqu'a Bet She'an Al-Yamun Deir Ghazala Dahiyat Sabah Al-Kheir Tal Menashe Umm Ar-Rihan Hinnanit Mashru' Beit Qad Built-up Areas and Land Reserves Kh. 'Abdallah Al-Yunis Dhaher Al-Malih Kafr Dan Shaqed 'Araqa Beit Qad Jalbun Rekhan Al-Hashimiya Tura-al-Gharbiya At-Tarem Barta'a Ash Sharqiya Jenin RC Jenin Nazlat Ash-Sheikh Zeid 2 Umm Dar Kaddim Kafr Qud Birqin Ganim Deir Abu-Da'if May 2002 Dhaher Al-'Abed Hadera Akkaba Ya'bad Kufeirit Qeiqis Zabda 'Arab As-Suweitat 60 Umm at-Tut Qaffin Imreiha Jalqamus Ash-Shuhada 585 Mevo Dotan Hermesh Al-Mughayyir Al-Mutilla Nazlat 'Isa Qabatiya Baqa Ash-Sharqiya An-Nazla Ash-Sharqiya Bir Al-Basha Ad-Damayra An-Nazla Al-Wusta Telfit Arraba Mirka Bardala An-Nazla Al-Gharbiya Fahma Al-Jadida Ein El-Beida Misiliya Fahma Raba Zeita Kardala Seida Az-Zababida Zawiya Al-Kufeir Mehola Attil Kfar Ra'i 60 Sir 3 Illar Ajja Anza Sanur Meithalun Shadmot Mehola Deir Al-Ghusun Ar-Rama Al-Jarushiya Tayasir Al-'Aqaba Al-Farisiya Sa Nur Nahal Rotem Al-Judeida Siris Tubas Netanya Shuweika Al-'Attara Jaba' Al-Malih Iktaba Bal'a Nahal Bitronot / Brosh Tulkarm RC Nur Shams RC Nahal Maskiyot Kafr Rumman Silat Adh-Dhahr Al-Fandaqumiya Dhinnaba 'Anabta Tulkarm Homesh Ras Al-Far'a Kafr al-Labad Bizzariya Burqa Yasid Al-Far'a RC Beit Imrin 'Izbat Shufa 578 90 Ramin Tammun Avne Hefez Al-Far'a Far'un Kafa Nisf Jubeil Enav Sabastiya 4 Shufa Talluza 57 Ijnisinya Kh.