An Update on Palestinian Movement, Access and Trade in the West Bank and Gaza

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nablus 3 Cluster Closures Jenin ‚ Checkpoint

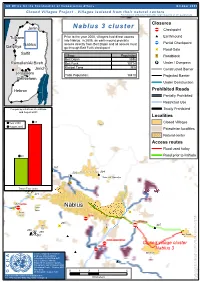

UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs October 2005 Closed Villages Project - Villages isolated from their natural centers Palestinians without permits (the large majority of the population) Nablus 3 cluster Closures Jenin ¬Ç Checkpoint ## Tulkarm Prior to the year 2000, villagers had direct access Earthmound into Nablus. In 2005, an earthmound prohibits ¬Ç Nablus access directly from Beit Dajan and all access must Partial Checkpoint Qalqiliya go through Beit Furik checkpoint D Road Gate Salfit Village Population /" Roadblock Beit Dajan 3696 Ramallah/Al Bireh Beit Furik 10714 º¹P Under / Overpass Jericho Khirbet Tana N/A Constructed Barrier Jerusalem Total Population: 14410 Projected Barrier Bethlehem Under Construction Hebron Prohibited Roads Partially ProhibitedTubas Restricted Use Comparing situations Pre-Intifada Totally Prohibited ## and August 2005 Tubas Burqa Localities 45 Closed Villages Year 2000 Yasid August 2005 Beit Imrin Palestinian localities Natural center Nisf Jubeil Access routes Sabastiya Ijnisinya Road used today 290 # 358#20Shave Shomeron Road prior to Intifada ¬Ç An Naqura 287 ## 389 'Asira ash Shamaliya 294 # 293 # ## ## 288¬Ç beit iba 'Asira ash Shamaliya /" Qusin Travel Time (min) 271 D 270Ç SARRA Nablus D ¬ Sarra Sarra Sarra D Sarra ¬Ç At Tur 279 beit furik cp the of part the 265 D ÇÇ 297 Tell ¬¬ delimitation the concerning # Tell # 269 ## ## 296## 268 ## # Beit Dajan 266#267 ## awarta commercial cp ¬Ç Closed village cluster ¬Ç huwwara Nablus 3 ## Closure mapping is a work in Beit Furik progress. Closure data is collected by OCHA field staff and is subject to change. ## Maps will be updated regularly. Cartography: OCHA Humanitarian Information Centre - October 2005 Base data: 03612 O C H A O C H OCHA update August 2005 For comments contact <[email protected]> Tel. -

Israeli Settlements in the Jordan Valley

Ü Bisan UV90 Givat Sa'alit UV60 Mechola The Occupied Shadmot Mehola Jordan Valley Rotem Tayasir (Northern Area) Occupied Palestine (West Bank) Maskiot Hemdat Ro'i Beka'ot UV57 UV90 Hamra Overview Hamra Jordan Valley Area 1948 Armatice Line Palestinian Communities UV57 Main & Bypass road Argaman Regional road Mechora Jk Crossing Points Israeli Settlements Built up area (Closed by Israel in 2000) Permeter Cultivated land UV60 Municipal boundries UV57 Massu'a Israeli Administrative Restrictions Damiya Gittit Interim Agreement Areas Area A Ma'ale Efrayim Jordan Area B Area C Closed Military Areas Ma'ale Efraim UV60 Yafit Israeli Physical Access Restrictions Ç !¬ Green Line checkpoint Ç !¬ Checkpoint Petza'el !Ǭ Partial Checkpoint ") Roadblock # Earthmound GÌ Road gate - closed GÌ Road gate - open Tomer DD DD DD DD DD DD Road barrier DDDDDDDDDD Earthwall Trench Gilgal Israeli Segregation Barrier Netiv Hagedud Constructed Under Construction Projected Niran Kochav Hashachar Ahavat Hayim Mitzpe Keramim Ma'ale Shlomo Yitav Rimmonim Jenin Yitav ( Al Auja) Tubas Omer Farm Tulkarm Nablus Mevo'ot Jericho Na'ama Tel Aviv-Yaffo Salfit Allenby / King Hussein Ramallah UV60 Jericho Jericho East Jerusalem Jericho Bethlehem Hebron UV90 Vered Yericho Givat Barkay Beit Holga - Mul Nevo Mitzpe Yericho Beit Ha`arava Kilometers 0 1 2 4 6 8 1 Dead Sea Ü UV90 Allenby / King Hussein Jericho UV90 The Occupied Jordan Valley Vered Yericho Givat Barkay Beit Holga - Mul Nevo (Southern Area) Occupied Palestine Mitzpe Yericho (West Bank) UV90 Beit Ha`arava Dead Sea Almog -

Migration of Eretz Yisrael Arabs Between December 1, 1947 and June 1, 1948

[Intelligence Service (Arab Section)] June 30, 1948 Migration of Eretz Yisrael Arabs between December 1, 1947 and June 1, 1948 Contents 1. General introduction. 2. Basic figures on Arab migration 3. National phases of evacuation and migration 4. Causes of Arab migration 5. Arab migration trajectories and absorption issues Annexes 1. Regional reviews analyzing migration issues in each area [Missing from document] 2. Charts of villages evacuated by area, noting the causes for migration and migration trajectories for every village General introduction The purpose of this overview is to attempt to evaluate the intensity of the migration and its various development phases, elucidate the different factors that impacted population movement directly and assess the main migration trajectories. Of course, given the nature of statistical figures in Eretz Yisrael in general, which are, in themselves, deficient, it would be difficult to determine with certainty absolute numbers regarding the migration movement, but it appears that the figures provided herein, even if not certain, are close to the truth. Hence, a margin of error of ten to fifteen percent needs to be taken into account. The figures on the population in the area that lies outside the State of Israel are less accurate, and the margin of error is greater. This review summarizes the situation up until June 1st, 1948 (only in one case – the evacuation of Jenin, does it include a later occurrence). Basic figures on Arab population movement in Eretz Yisrael a. At the time of the UN declaration [resolution] regarding the division of Eretz Yisrael, the following figures applied within the borders of the Hebrew state: 1. -

The Economic Base of Israel's Colonial Settlements in the West Bank

Palestine Economic Policy Research Institute The Economic Base of Israel’s Colonial Settlements in the West Bank Nu’man Kanafani Ziad Ghaith 2012 The Palestine Economic Policy Research Institute (MAS) Founded in Jerusalem in 1994 as an independent, non-profit institution to contribute to the policy-making process by conducting economic and social policy research. MAS is governed by a Board of Trustees consisting of prominent academics, businessmen and distinguished personalities from Palestine and the Arab Countries. Mission MAS is dedicated to producing sound and innovative policy research, relevant to economic and social development in Palestine, with the aim of assisting policy-makers and fostering public participation in the formulation of economic and social policies. Strategic Objectives Promoting knowledge-based policy formulation by conducting economic and social policy research in accordance with the expressed priorities and needs of decision-makers. Evaluating economic and social policies and their impact at different levels for correction and review of existing policies. Providing a forum for free, open and democratic public debate among all stakeholders on the socio-economic policy-making process. Disseminating up-to-date socio-economic information and research results. Providing technical support and expert advice to PNA bodies, the private sector, and NGOs to enhance their engagement and participation in policy formulation. Strengthening economic and social policy research capabilities and resources in Palestine. Board of Trustees Ghania Malhees (Chairman), Ghassan Khatib (Treasurer), Luay Shabaneh (Secretary), Mohammad Mustafa, Nabeel Kassis, Radwan Shaban, Raja Khalidi, Rami Hamdallah, Sabri Saidam, Samir Huleileh, Samir Abdullah (Director General). Copyright © 2012 Palestine Economic Policy Research Institute (MAS) P.O. -

Return of Private Foundation

l efile GRAPHIC p rint - DO NOT PROCESS As Filed Data - DLN: 93491015004014 Return of Private Foundation OMB No 1545-0052 Form 990 -PF or Section 4947( a)(1) Nonexempt Charitable Trust Treated as a Private Foundation Department of the Treasury 2012 Note . The foundation may be able to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting requirements Internal Revenue Service • . For calendar year 2012 , or tax year beginning 06 - 01-2012 , and ending 05-31-2013 Name of foundation A Employer identification number CENTURY 21 ASSOCIATES FOUNDATION INC 22-2412138 O/o RAYMOND GINDI ieiepnone number (see instructions) Number and street (or P 0 box number if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite U 22 CORTLANDT STREET Suite City or town, state, and ZIP code C If exemption application is pending, check here F NEW YORK, NY 10007 G Check all that apply r'Initial return r'Initial return of a former public charity D 1. Foreign organizations, check here (- r-Final return r'Amended return 2. Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, r Address change r'Name change check here and attach computation H Check type of organization FSection 501(c)(3) exempt private foundation r'Section 4947(a)(1) nonexempt charitable trust r'Other taxable private foundation J Accounting method F Cash F Accrual E If private foundation status was terminated I Fair market value of all assets at end und er section 507 ( b )( 1 )( A ), c hec k here F of y e a r (from Part 77, col. (c), Other (specify) _ F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination line 16)x$ 4,783,143 -

November 2014 Al-Malih Shaqed Kh

Salem Zabubah Ram-Onn Rummanah The West Bank Ta'nak Ga-Taybah Um al-Fahm Jalameh / Mqeibleh G Silat 'Arabunah Settlements and the Separation Barrier al-Harithiya al-Jalameh 'Anin a-Sa'aidah Bet She'an 'Arrana G 66 Deir Ghazala Faqqu'a Kh. Suruj 6 kh. Abu 'Anqar G Um a-Rihan al-Yamun ! Dahiyat Sabah Hinnanit al-Kheir Kh. 'Abdallah Dhaher Shahak I.Z Kfar Dan Mashru' Beit Qad Barghasha al-Yunis G November 2014 al-Malih Shaqed Kh. a-Sheikh al-'Araqah Barta'ah Sa'eed Tura / Dhaher al-Jamilat Um Qabub Turah al-Malih Beit Qad a-Sharqiyah Rehan al-Gharbiyah al-Hashimiyah Turah Arab al-Hamdun Kh. al-Muntar a-Sharqiyah Jenin a-Sharqiyah Nazlat a-Tarem Jalbun Kh. al-Muntar Kh. Mas'ud a-Sheikh Jenin R.C. A'ba al-Gharbiyah Um Dar Zeid Kafr Qud 'Wadi a-Dabi Deir Abu Da'if al-Khuljan Birqin Lebanon Dhaher G G Zabdah לבנון al-'Abed Zabdah/ QeiqisU Ya'bad G Akkabah Barta'ah/ Arab a-Suweitat The Rihan Kufeirit רמת Golan n 60 הגולן Heights Hadera Qaffin Kh. Sab'ein Um a-Tut n Imreihah Ya'bad/ a-Shuhada a a G e Mevo Dotan (Ganzour) n Maoz Zvi ! Jalqamus a Baka al-Gharbiyah r Hermesh Bir al-Basha al-Mutilla r e Mevo Dotan al-Mughayir e t GNazlat 'Isa Tannin i a-Nazlah G d Baqah al-Hafira e The a-Sharqiya Baka al-Gharbiyah/ a-Sharqiyah M n a-Nazlah Araba Nazlat ‘Isa Nazlat Qabatiya הגדה Westהמערבית e al-Wusta Kh. -

Nablus Salfit Tubas Tulkarem

Iktaba Al 'Attara Siris Jaba' (Jenin) Tulkarem Kafr Rumman Silat adh DhahrAl Fandaqumiya Tubas Kashda 'Izbat Abu Khameis 'Anabta Bizzariya Khirbet Yarza 'Izbat al Khilal Burqa (Nablus) Kafr al Labad Yasid Kafa El Far'a Camp Al Hafasa Beit Imrin Ramin Ras al Far'a 'Izbat Shufa Al Mas'udiya Nisf Jubeil Wadi al Far'a Tammun Sabastiya Shufa Ijnisinya Talluza Khirbet 'Atuf An Naqura Saffarin Beit Lid Al Badhan Deir Sharaf Al 'Aqrabaniya Ar Ras 'Asira ash Shamaliya Kafr Sur Qusin Zawata Khirbet Tall al Ghar An Nassariya Beit Iba Shida wa Hamlan Kur 'Ein Beit el Ma Camp Beit Hasan Beit Wazan Ein Shibli Kafr ZibadKafr 'Abbush Al Juneid 'Azmut Kafr Qaddum Nablus 'Askar Camp Deir al Hatab Jit Sarra Salim Furush Beit Dajan Baqat al HatabHajja Tell 'Iraq Burin Balata Camp 'Izbat Abu Hamada Kafr Qallil Beit Dajan Al Funduq ImmatinFar'ata Rujeib Madama Burin Kafr Laqif Jinsafut Beit Furik 'Azzun 'Asira al Qibliya 'Awarta Yanun Wadi Qana 'Urif Khirbet Tana Kafr Thulth Huwwara Odala 'Einabus Ar Rajman Beita Zeita Jamma'in Ad Dawa Jafa an Nan Deir Istiya Jamma'in Sanniriya Qarawat Bani Hassan Aqraba Za'tara (Nablus) Osarin Kifl Haris Qira Biddya Haris Marda Tall al Khashaba Mas-ha Yasuf Yatma Sarta Dar Abu Basal Iskaka Qabalan Jurish 'Izbat Abu Adam Talfit Qusra Salfit As Sawiya Majdal Bani Fadil Rafat (Salfit) Khirbet Susa Al Lubban ash Sharqiya Bruqin Farkha Qaryut Jalud Kafr ad Dik Khirbet Qeis 'Ammuriya Khirbet Sarra Qarawat Bani Zeid (Bani Zeid al Gharb Duma Kafr 'Ein (Bani Zeid al Gharbi)Mazari' an Nubani (Bani Zeid qsh Shar Khirbet al Marajim 'Arura (Bani Zeid qsh Sharqiya) Bani Zeid 'Abwein (Bani Zeid ash Sharqiya) Sinjil Turmus'ayya. -

Annual Report #4

Fellow engineers Annual Report #4 Program Name: Local Government & Infrastructure (LGI) Program Country: West Bank & Gaza Donor: USAID Award Number: 294-A-00-10-00211-00 Reporting Period: October 1, 2013 - September 30, 2014 Submitted To: Tony Rantissi / AOR / USAID West Bank & Gaza Submitted By: Lana Abu Hijleh / Country Director/ Program Director / LGI 1 Program Information Name of Project1 Local Government & Infrastructure (LGI) Program Country and regions West Bank & Gaza Donor USAID Award number/symbol 294-A-00-10-00211-00 Start and end date of project September 30, 2010 – September 30, 2015 Total estimated federal funding $100,000,000 Contact in Country Lana Abu Hijleh, Country Director/ Program Director VIP 3 Building, Al-Balou’, Al-Bireh +972 (0)2 241-3616 [email protected] Contact in U.S. Barbara Habib, Program Manager 8601 Georgia Avenue, Suite 800, Silver Spring, MD USA +1 301 587-4700 [email protected] 2 Table of Contents Acronyms and Abbreviations …………………………………….………… 4 Program Description………………………………………………………… 5 Executive Summary…………………………………………………..…...... 7 Emergency Humanitarian Aid to Gaza……………………………………. 17 Implementation Activities by Program Objective & Expected Results 19 Objective 1 …………………………………………………………………… 24 Objective 2 ……………………................................................................ 42 Mainstreaming Green Elements in LGI Infrastructure Projects…………. 46 Objective 3…………………………………………………........................... 56 Impact & Sustainability for Infrastructure and Governance ……............ -

English Version

:ÎÊ·ÇAÎj?fb< “Preliminary Study” e content of this publication is the sole responsibility of ARIJ and can under no circumstances be regarded as reecting the position of RLS Trading your Neighbours Water 1 Table Of Contents 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 3 2. Existing Research ...................................................................................................................... 4 3. Main Findings ................................................................................................................................ 6 3.1. Water Allocation ................................................................................................................ 6 3.2. Agriculture .........................................................................................................................12 3.3. Product Export .................................................................................................................18 3.4. Virtual Water ....................................................................................................................19 4. Conclusion ..................................................................................................................................21 5. Recommendations .....................................................................................................................22 List Of Tables Table 1: The water allocation to the settlements -

Avoiding Last Period Defection Within Israeli-Palestinian Final

Breaking the Stalemate: Avoiding Last Period Defection within Israeli-Palestinian Final Status Negotiations through Statistical Modeling John J. Villa Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for a B.A. with Honors From the Political Science Department at Duke University March 31, 2017 1 Forward: --First, I must thank the phenomenal Political Science Department at Duke University and my thesis advisor Dr. Michael C. Munger for their tremendous support while I developed my thesis and during my general education. Dr. Munger’s leadership, creativity, and generosity provided the foundation upon which I write to you, and his impact upon this publication was critical. --To Dr. Abdeslam E. M. Maghraoui, thank you for instructing me in three tremendous Middle East Studies courses and helping me establish the foundational aspects of this publication. Your mentorship and sharing of knowledge provided an entry point into subject matter far beyond anything I ever thought I would reach. -- To Dr. Mbaye Lo, thank you for your unwavering support, challenging materials, and educated discussions. Our long debates in your office are some of my fondest memories of my time in Durham. --To the staff of the Data Visualization Lab staff at Duke University consisting of Mark Thomas, Angela Zoss, John Little, and Jena Happ, your expertise, patience, and assistance in ArcGIS, Open Refine, and general data manipulation were extremely helpful during the computational portion of this publication and for that I thank you. --To Ryan Denniston, your assistance in Microsoft Excel functions and ArcGIS modeling was impeccable. This is, of course, in addition to your generosity, patience, and creatively which I’m sure were tested day after day coding together in the lab as you guided me through the ever-more complex ArcGIS models. -

Ground to a Halt, Denial of Palestinians' Freedom Of

Since the beginning of the second intifada, in September 2000, Israel has imposed restrictions on the movement of Palestinians in the West Bank that are unprecedented in scope and duration. As a result, Palestinian freedom of movement, which was limited in any event, has turned from a fundamental human right to a privilege that Israel grants or withholds as it deems fit. The restrictions have made traveling from one section to another an exceptional occurrence, subject to various conditions and a showing of justification for the journey. Almost every trip in the West Bank entails a great loss of time, much uncertainty, friction with soldiers, and often substantial additional expense. The restrictions on movement that Israel has imposed on Palestinians in the West Bank have split the West Bank into six major geographical units: North, Central, South, the Jordan Valley and northern Dead Sea, the enclaves resulting from the Separation Barrier, and East Jerusalem. In addition to the restrictions on movement from area to area, Israel also severely restricts movement within each area by splitting them up into subsections, and by controlling and limiting movement between them. This geographic division of the West Bank greatly affects every aspect of Palestinian life. B’TSELEM - The Israeli Information Center for Human Rights in the Occupied Territories Ground to a Halt 8 Hata’asiya St., Talpiot P.O. Box 53132 Jerusalem 91531 Denial of Palestinians’ Freedom Tel. (972) 2-6735599 Fax. (972) 2-6749111 of Movement in the West Bank www.btselem.org • [email protected] August 2007 Ground to a Halt Denial of Palestinians’ Freedom of Movement in the West Bank August 2007 Stolen land is concrete, so here and there calls are heard to stop the building in settlements and not to expropriate land. -

Al-Bireh Ramallah Salfit

Biddya Haris Kifl Haris Marda Tall al Khashaba Mas-ha Yasuf Yatma Sarta Dar Abu Basal Iskaka Qabalan Jurish 'Izbat Abu Adam Az Zawiya (Salfit) Talfit Salfit As Sawiya Qusra Majdal Bani Fadil Rafat (Salfit) Khirbet Susa Al Lubban ash Sharqiya Bruqin Farkha Qaryut Jalud Deir Ballut Kafr ad Dik Khirbet Qeis 'Ammuriya Khirbet Sarra Qarawat Bani Zeid (Bani Zeid al Gharb Duma Kafr 'Ein (Bani Zeid al Gharbi)Mazari' an Nubani (Bani Zeid qsh Shar Khirbet al Marajim 'Arura (Bani Zeid qsh Sharqiya) Turmus'ayya Al Lubban al Gharbi 'Abwein (Bani Zeid ash Sharqiya) Bani Zeid Deir as Sudan Sinjil Rantis Jilijliya 'Ajjul An Nabi Salih (Bani Zeid al Gharbi) Al Mughayyir (Ramallah) 'Abud Khirbet Abu Falah Umm Safa Deir Nidham Al Mazra'a ash Sharqiya 'Atara Deir Abu Mash'al Jibiya Kafr Malik 'Ein Samiya Shuqba Kobar Burham Silwad Qibya Beitillu Shabtin Yabrud Jammala Ein Siniya Bir Zeit Budrus Deir 'Ammar Silwad Camp Deir Jarir Abu Shukheidim Jifna Dura al Qar' Abu Qash At Tayba (Ramallah) Deir Qaddis Al Mazra'a al Qibliya Al Jalazun Camp 'Ein Yabrud Ni'lin Kharbatha Bani HarithRas Karkar Surda Al Janiya Al Midya Rammun Bil'in Kafr Ni'ma 'Ein Qiniya Beitin Badiw al Mus'arrajat Deir Ibzi' Deir Dibwan 'Ein 'Arik Saffa Ramallah Beit 'Ur at Tahta Khirbet Kafr Sheiyan Al-Bireh Burqa (Ramallah) Beituniya Al Am'ari Camp Beit Sira Kharbatha al Misbah Beit 'Ur al Fauqa Kafr 'Aqab Mikhmas Beit Liqya At Tira Rafat (Jerusalem) Qalandiya Camp Qalandiya Beit Duqqu Al Judeira Jaba' (Jerusalem) Al Jib Jaba' (Tajammu' Badawi) Beit 'Anan Bir Nabala Beit Ijza Ar Ram & Dahiyat al Bareed Deir al Qilt Kharayib Umm al Lahim QatannaAl Qubeiba Biddu An Nabi Samwil Beit Hanina Hizma Beit Hanina al Balad Beit Surik Beit Iksa Shu'fat 'Anata Shu'fat Camp Al Khan al Ahmar (Tajammu' Badawi) Al 'Isawiya.