Burundi Overview Page 1 of 4

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Situation Report #2, Fiscal Year (FY) 2003 March 25, 2003 Note: the Last Situation Report Was Dated November 18, 2002

U.S. AGENCY FOR INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT BUREAU FOR DEMOCRACY, CONFLICT, AND HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE (DCHA) OFFICE OF U.S. FOREIGN DISASTER ASSISTANCE (OFDA) BURUNDI – Complex Emergency Situation Report #2, Fiscal Year (FY) 2003 March 25, 2003 Note: The last situation report was dated November 18, 2002. BACKGROUND The Tutsi minority, which represents 14 percent of Burundi’s 6.85 million people, has dominated the country politically, militarily, and economically since national independence in 1962. Approximately 85 percent of Burundi’s population is Hutu, and approximately one percent is Twa (Batwa). The current cycle of violence began in October 1993 when members within the Tutsi-dominated army assassinated the first freely elected President, Melchoir Ndadaye (Hutu), sparking Hutu-Tutsi fighting. Ndadaye’s successor, Cyprien Ntariyama (Hutu), was killed in a plane crash on April 6, 1994, alongside Rwandan President Habyarimana. Sylvestre Ntibantunganya (Hutu) took power and served as President until July 1996, when a military coup d’etat brought current President Pierre Buyoya (Tutsi) to power. Since 1993, an estimated 300,000 Burundians have been killed. In August 2000, nineteen Burundian political parties signed the Peace and Reconciliation Agreement in Arusha, Tanzania, overseen by peace process facilitator, former South African President Nelson Mandela. The Arusha Peace Accords include provisions for an ethnically balanced army and legislature, and for democratic elections to take place after three years of transitional government. The three-year transition period began on November 1, 2001. President Pierre Buyoya is serving as president for the first 18 months of the transition period, to be followed in May 2003 by a Hutu president for the final 18 months. -

Burundi: Breaking the Deadlock

BURUNDI: BREAKING THE DEADLOCK The Urgent Need For A New Negotiating Framework 14 May 2001 Africa Report No. 29 Brussels/Nairobi TABLE OF CONTENTS MAP OF BURUNDI............................................................................................................ i OVERVIEW AND RECOMMENDATIONS.................................................................ii INTRODUCTION.............................................................................................................. 1 A. A CEASE-FIRE REMAINS IMPROBABLE..................................................................... 2 B. THE FDD FROM LIBREVILLE I TO LIBREVILLE II: OUT WEST, NOTHING MUCH NEW?.............................................................................................................. 3 1. The initial shock: Laurent Kabila's legacy ..........................................................3 2. Libreville II, and afterwards? ..............................................................................4 3. Compensating for the shortcomings of being a mercenary force........................5 C. AGATHON RWASA IN POWER, UNCERTAIN CHANGE IN THE FNL........................... 7 1. The origin of the overthrow of Cossan Kabura ...................................................7 2. Interpreting the attack on Kinama .......................................................................7 3. The alliance of the ex-FAR and FDD: a poorly-calculated risk..........................9 D. THE HUMANITARIAN CATASTROPHE .................................................................... -

Entanglements of Modernity, Colonialism and Genocide Burundi and Rwanda in Historical-Sociological Perspective

UNIVERSITY OF LEEDS Entanglements of Modernity, Colonialism and Genocide Burundi and Rwanda in Historical-Sociological Perspective Jack Dominic Palmer University of Leeds School of Sociology and Social Policy January 2017 Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy ii The candidate confirms that the work submitted is their own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. ©2017 The University of Leeds and Jack Dominic Palmer. The right of Jack Dominic Palmer to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by Jack Dominic Palmer in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would firstly like to thank Dr Mark Davis and Dr Tom Campbell. The quality of their guidance, insight and friendship has been a huge source of support and has helped me through tough periods in which my motivation and enthusiasm for the project were tested to their limits. I drew great inspiration from the insightful and constructive critical comments and recommendations of Dr Shirley Tate and Dr Austin Harrington when the thesis was at the upgrade stage, and I am also grateful for generous follow-up discussions with the latter. I am very appreciative of the staff members in SSP with whom I have worked closely in my teaching capacities, as well as of the staff in the office who do such a great job at holding the department together. -

Burundi: the Issues at Stake

BURUNDI: THE ISSUES AT STAKE. POLITICAL PARTIES, FREEDOM OF THE PRESS AND POLITICAL PRISONERS 12 July 2000 ICG Africa Report N° 23 Nairobi/Brussels (Original Version in French) Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY..........................................................................................i INTRODUCTION...................................................................................................1 I. POLITICAL PARTIES: PURGES, SPLITS AND CRACKDOWNS.........................1 A. Beneficiaries of democratisation turned participants in the civil war (1992-1996)3 1. Opposition groups with unclear identities ................................................. 4 2. Resorting to violence to gain or regain power........................................... 7 B. Since the putsch: dangerous games of the government................................... 9 1. Purge of opponents to the peace process (1996-1998)............................ 10 2. Harassment of militant activities ............................................................ 14 C. Institutionalisation of political opportunism................................................... 17 1. Partisan putsches and alliances of convenience....................................... 18 2. Absence of fresh political attitudes......................................................... 20 D. Conclusion ................................................................................................. 23 II WHICH FREEDOM FOR WHAT MEDIA ?...................................................... 25 A. Media -

Burundi: T Prospects for Peace • BURUNDI: PROSPECTS for PEACE an MRG INTERNATIONAL REPORT an MRG INTERNATIONAL

Minority Rights Group International R E P O R Burundi: T Prospects for Peace • BURUNDI: PROSPECTS FOR PEACE AN MRG INTERNATIONAL REPORT AN MRG INTERNATIONAL BY FILIP REYNTJENS BURUNDI: Acknowledgements PROSPECTS FOR PEACE Minority Rights Group International (MRG) gratefully acknowledges the support of Trócaire and all the orga- Internally displaced © Minority Rights Group 2000 nizations and individuals who gave financial and other people. Child looking All rights reserved assistance for this Report. after his younger Material from this publication may be reproduced for teaching or other non- sibling. commercial purposes. No part of it may be reproduced in any form for com- This Report has been commissioned and is published by GIACOMO PIROZZI/PANOS PICTURES mercial purposes without the prior express permission of the copyright holders. MRG as a contribution to public understanding of the For further information please contact MRG. issue which forms its subject. The text and views of the A CIP catalogue record for this publication is available from the British Library. author do not necessarily represent, in every detail and in ISBN 1 897 693 53 2 all its aspects, the collective view of MRG. ISSN 0305 6252 Published November 2000 MRG is grateful to all the staff and independent expert Typeset by Texture readers who contributed to this Report, in particular Kat- Printed in the UK on bleach-free paper. rina Payne (Commissioning Editor) and Sophie Rich- mond (Reports Editor). THE AUTHOR Burundi: FILIP REYNTJENS teaches African Law and Politics at A specialist on the Great Lakes Region, Professor Reynt- the universities of Antwerp and Brussels. -

The Catholic Understanding of Human Rights and the Catholic Church in Burundi

Human Rights as Means for Peace : the Catholic Understanding of Human Rights and the Catholic Church in Burundi Author: Fidele Ingiyimbere Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/2475 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Electronic Thesis or Dissertation, 2011 Copyright is held by the author, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise noted. BOSTON COLLEGE-SCHOOL OF THEOLOGY AND MINISTY S.T.L THESIS Human Rights as Means for Peace The Catholic Understanding of Human Rights and the Catholic Church in Burundi By Fidèle INGIYIMBERE, S.J. Director: Prof David HOLLENBACH, S.J. Reader: Prof Thomas MASSARO, S.J. February 10, 2011. 1 Contents Contents ...................................................................................................................................... 0 General Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 2 CHAP. I. SETTING THE SCENE IN BURUNDI ......................................................................... 8 I.1. Historical and Ecclesial Context........................................................................................... 8 I.2. 1972: A Controversial Period ............................................................................................. 15 I.3. 1983-1987: A Church-State Conflict .................................................................................. 22 I.4. 1993-2005: The Long Years of Tears................................................................................ -

ECFG-Burundi-2020R.Pdf

About this Guide This guide is designed to prepare you to deploy to culturally complex environments and achieve mission objectives. The fundamental information contained within will help you understand the cultural dimension of your assigned location and gain skills necessary for success. ECFG The guide consists of 2 parts: Part 1 introduces “Culture General,” the foundational knowledge you need to operate effectively in any global environment. Burundi Part 2 presents “Culture Specific” Burundi, focusing on unique cultural features of Burundian society and is designed to complement other pre-deployment training. It applies culture- general concepts to help increase your knowledge of your assigned deployment location (Photo courtesy of IRIN News © Jane Some). For further information, visit the Air Force Culture and Language Center (AFCLC) website at www.airuniversity.af.edu/AFCLC/ or contact AFCLC’s Region Team at [email protected]. Disclaimer: All text is the property of the AFCLC and may not be modified by a change in title, content, or labeling. It may be reproduced in its current format with the expressed permission of the AFCLC. All photography is provided as a courtesy of the US government, Wikimedia, and other sources as indicated. GENERAL CULTURE CULTURE PART 1 – CULTURE GENERAL What is Culture? Fundamental to all aspects of human existence, culture shapes the way humans view life and functions as a tool we use to adapt to our social and physical environments. A culture is the sum of all of the beliefs, values, behaviors, and symbols that have meaning for a society. All human beings have culture, and individuals within a culture share a general set of beliefs and values. -

The U.S. Response to the Burundi Genocide of 1972

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Masters Theses The Graduate School Spring 2012 The .SU . response to the Burundi Genocide of 1972 Jordan D. Taylor James Madison University Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/master201019 Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Taylor, Jordan D., "The .SU . response to the Burundi Genocide of 1972" (2012). Masters Theses. 347. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/master201019/347 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the The Graduate School at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The U.S. Response to the Burundi Genocide of 1972 Jordan D. Taylor A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of JAMES MADISON UNIVERSITY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts History May 2012 Dedication For my family ! ii! Acknowledgements I would like to thank my thesis committee for helping me with this project. Dr. Guerrier, your paper edits and insights into America during the 1970s were invaluable. Dr. Owusu-Ansah, you helped me understand the significant impacts of the Belgian colonial legacy on independent Burundi. Dr. Seth, you provided challenging questions about the inherent conflicts between national sovereignty and humanitarian intervention. All these efforts, and many more, have helped to strengthen my thesis. I would also like to give a special thanks to my parents. Dad, your work on the Nigerian Civil War served as my guiding light throughout this project, and mom, I never would have been able to transcribe the Nixon Tapes without your help. -

Will Hutus and Tutsis Live Together Peacefully ?

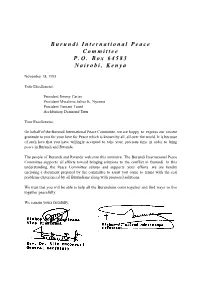

B u r u n d i I n t e r n a t i o n a l P e a c e C o m m i t t e e P . O . B o x 6 4 5 8 3 N a i r o b i , K e n y a November 18, 1995 Your Excellencies. President Jimmy Carter President Mwalimu Julius K. Nyerere President Tumani TourŽ Archbishop Desmond Tutu Your Excellencies, On behalf of the Burundi International Peace Committee, we are happy to express our sincere gratitude to you for your love for Peace which is known by all, all over the world. It is because of such love that you have willingly accepted to take your precious time in order to bring peace in Burundi and Rwanda. The people of Rurundi and Rwanda welcome this initiative. The Burundi International Peace Committee supports all efforts toward bringing solutions to the conflict in Burundi. In this understanding, the Peace Committee salutes and supports your efforts. we are hereby enclosing a document prepared by the committee to assist you come to terms with the real problems experienced by all Burundians along with proposed solutions. We trust that you will be able to help all the Burundians come together and find ways to live together peacefully. We remain yours faithfully, WILL HUTUS AND TUTSIS LIVE TOGETHER PEACEFULLY ? Introduction More than two years have passed since the assassination of President Melchior Ndadaye of Burundi. Since then, many people have lost their lives and continue to die. One wonders whether it will be possible again for Hutus and Tutsis to live together peacefully. -

Stoking the Fires

STOKING THE FIRES Military Assistance and Arms Trafficking in Burundi Human Rights Watch Arms Project Human Rights Watch New York AAA Washington AAA London AAA Brussels Copyright 8 December 1997 by Human Rights Watch All Rights Reserved Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-177-0 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 97-80896 Human Rights Watch Arms Project The Human Rights Watch Arms Project was established in 1992 to monitor and prevent arms transfers to governments or organizations that commit gross violations of internationally recognized human rights and the rules of war and promote freedom of information regarding arms transfers worldwide. Joost R. Hiltermann is the director; Stephen D. Goose is the program director; Loretta Bondì is the Advocacy Coordinator; Andrew Cooper, and Ernst Jan Hogendoorn are research assistants; Rebecca Bell is the associate; William M. Arkin, Kathi L. Austin, Dan Connell, Monica Schurtman, and Frank Smyth are consultants. Torsten N. Wiesel is the chair of the board and Nicole Ball and Vincent McGee are the vice-chairs. Addresses for Human Rights Watch 485 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10017-6104 Tel: (212) 972-8400, Fax: (212) 972-0905, E-mail: [email protected] 1522 K Street, N.W., #910, Washington, DC 20005-1202 Tel: (202) 371-6592, Fax: (202) 371-0124, E-mail: [email protected] 33 Islington High Street, N1 9LH London, UK Tel: (171) 713-1995, Fax: (171) 713-1800, E-mail: [email protected] 15 Rue Van Campenhout, 1000 Brussels, Belgium Tel: (2) 732-2009, Fax: (2) 732-0471, E-mail: [email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org Listserv address: To subscribe to the list, send an e-mail message to [email protected] with Asubscribe hrw-news@ in the body of the message (leave the subject line blank). -

Burundi Conflict Insight | Feb 2018 | Vol

IPSS Peace & Security Report ABOUT THE REPORT The purpose of this report is to provide analysis and recommendations to assist the African Union (AU), Burundi Conflict Regional Economic Communities (RECs), Member States and Development Partners in decision making and in the implementation of peace and security- related instruments. Insight CONTRIBUTORS Dr. Mesfin Gebremichael (Editor in Chief) Mr. Alagaw Ababu Kifle Ms. Alem Kidane Mr. Hervé Wendyam Ms. Mahlet Fitiwi Ms. Zaharau S. Shariff EDITING, DESIGN & LAYOUT Michelle Mendi Muita (Editor) Situation analysis Mikias Yitbarek (Design & Layout) Since gaining independence in 1962, Burundi has experienced several violent conflicts, including a civil war that took place between 1993 and © 2018 Institute for Peace and Security Studies, 2005. The common denominator of these conflicts was the politicization of Addis Ababa University. All rights reserved. divisions between the Hutu and Tutsi ethnic groups. The civil war was triggered by the assassination of the first democratically elected president, Melchior Ndadaye, by Tutsi elements in a failed attempt to overthrow the February 2018 | Vol. 1 government. The civil war is estimated to have caused more than 300,000 deaths and over 1 million displacements. In order to bring the civil war to CONTENTS an end, three major agreements were signed with varying degrees of Situation analysis 1 success, namely, the 1994 Convention of Government, the 2000 Arusha Causes of the conflict 2 Peace and Reconciliation Agreement,i and the 2004 Burundi Power-Sharing Actors 3 Agreement. Dynamics of the conflict 5 Scenarios 6 Current response assessment 6 Strategic options 7 Timeline 9 References 11 i In an attempt to bring the civil war to an end, Julius Nyerere (former President of Tanzania) and Nelson Mandela (former President of South Africa), facilitated a lengthy negotiation between the Hutus and the Tutsis. -

L'origine De La Scission Au Sein U CNDD-FDD

AFRICA Briefing Nairobi/Brussels, 6 August 2002 THE BURUNDI REBELLION AND THE CEASEFIRE NEGOTIATIONS I. OVERVIEW Domitien Ndayizeye, but there is a risk this will not happen if a ceasefire is not agreed soon. This would almost certainly collapse the entire Arusha Prospects are still weak for a ceasefire agreement in framework. FRODEBU – Buyoya’s transition Burundi that includes all rebel factions. Despite the partner and the main Hutu political party – would Arusha agreement in August 2000 and installation have to concede the Hutu rebels’ chief criticism, of a transition government on 1 November 2001, the that it could not deliver on the political promises it warring parties, the Burundi army and the various made in signing Arusha. The fractious coalition factions of the Party for the Liberation of the Hutu would appear a toothless partner in a flawed People/National Liberation Forces (PALIPEHUTU- power-sharing deal with a government that had no FNL) and of the National Council for the Defense intention of reforming. All this would likely lead to of Democracy/Defense Forces of Democracy escalation rather than an end to fighting. (CNDD-FDD), are still fighting. Neither side has been able to gain a decisive military advantage, This briefing paper provides information about although the army recently claimed several and a context for understanding the rebel factions, important victories. whose history, objectives and internal politics are little known outside Burundi. It analyses their A ceasefire – the missing element in the Arusha dynamics, operational situations and negotiating framework – has been elusive despite on-going positions and is a product of extensive field activity by the South African facilitation team to research conducted in Tanzania and in Burundi, initiate joint and separate talks with the rebels.