The Parable of the Prodigal Son 19 IV

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

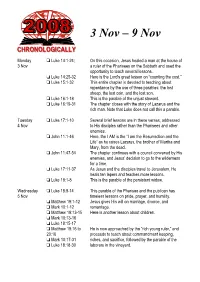

Monday 3 Nov Tuesday 4 Nov Wednesday 5 Nov Luke 14:1-24

Monday Luke 14:1-24; On this occasion, Jesus healed a man at the house of 3 Nov a ruler of the Pharisees on the Sabbath and used the opportunity to teach several lessons. Luke 14:25-32 Here is the Lord's great lesson on “counting the cost.” Luke 15:1-32 This entire chapter is devoted to teaching about repentance by the use of three parables: the lost sheep, the lost coin, and the lost son. Luke 16:1-18 This is the parable of the unjust steward. Luke 16:19-31 The chapter closes with the story of Lazarus and the rich man. Note that Luke does not call this a parable. Tuesday Luke 17:1-10 Several brief lessons are in these verses, addressed 4 Nov to His disciples rather than the Pharisees and other enemies. John 11:1-46 Here, the I AM is the “I am the Resurrection and the Life” as he raises Lazarus, the brother of Martha and Mary, from the dead. John 11:47-54 The chapter continues with a council convened by His enemies, and Jesus' decision to go to the wilderness for a time. Luke 17:11-37 As Jesus and the disciples travel to Jerusalem, He heals ten lepers and teaches more lessons. Luke 18:1-8 This is the parable of the persistent widow. Wednesday Luke 18:9-14 This parable of the Pharisee and the publican has 5 Nov timeless lessons on pride, prayer, and humility. Matthew 19:1-12 Jesus gives His will on marriage, divorce, and Mark 10:1-12 remarriage. -

The Parables of Jesus

THE NEW TESTAMENT PARABLES OF JESUS Year 1– Quarter 4 by F. L. Booth ©2005 F. L. Booth Zion, IL 60099 CONTENTS PAGE PREFACE CHART NO. 1 - Parables of Jesus in Chronological Order CHART NO. 2 - Classification of the Parables of Jesus LESSON 1 - Parables of the Kingdom No. 1 The Parable of the Sower 1 - 1 LESSON 2 - Parables of the Kingdom No. 2 I. The Parable of the Tares 2 - 1 II. The Parable of the Seed Growing in Secret 2 - 3 III. The Parable of the Mustard Seed 2 - 5 IV. The Parable of the Leaven 2 - 7 LESSON 3 - Parables of the Kingdom No. 3 I. The Parable of the Hidden Treasure 3 - 1 II. The Parable of the Pearl of Great Price 3 - 3 III. The Parable of the Drawnet 3 - 5 IV. The Parable of the Laborers in the Vineyard 3 - 7 LESSON 4 - Parables of Forgiveness I. The Parable of the Two Debtors 4 - 1 II. The Parable of the Unmerciful Servant 4 - 5 LESSON 5 - A Parable of the Love of One's Neighbor The Parable of the Good Samaritan 5 - 1 A Parable of Jews and Gentiles The Parable of the Wicked Husbandmen 5 - 4 LESSON 6 - Parables of Praying I. The Parable of the Friend at Midnight 6 - 1 II. The Parable of the Importunate Widow 6 - 3 LESSON 7 - Parables of Self-Righteousness and Humility I. The Parable of the Chief Seats 7 - 1 II. The Parable of the Pharisee and the Publican 7 - 3 LESSON 8 - Parables of the Cost of Discipleship I. -

Praise & Worship from Moody Radio

Praise & Worship from Moody Radio 04/28/15 Tuesday 12 A (CT) Air Time (CT) Title Artist Album 12:00:10 AM Hold Me Jesus Big Daddy Weave Every Time I Breathe (2006) 12:03:59 AM Do Something Matthew West Into The Light 12:07:59 AM Wonderful Merciful Savior Selah Press On (2001) 12:12:20 AM Jesus Loves Me Chris Tomlin Love Ran Red (2014) 12:15:45 AM Crown Him With Many Crowns Michael W. Smith/Anointed I'll Lead You Home (1995) 12:21:51 AM Gloria Todd Agnew Need (2009) 12:24:36 AM Glory Phil Wickham The Ascension (2013) 12:27:47 AM Do Everything Steven Curtis Chapman Do Everything (2011) 12:31:29 AM O Love Of God Laura Story God Of Every Story (2013) 12:34:26 AM Hear My Worship Jaime Jamgochian Reason To Live (2006) 12:37:45 AM Broken Together Casting Crowns Thrive (2014) 12:42:04 AM Love Has Come Mark Schultz Come Alive (2009) 12:45:49 AM Reach Beyond Phil Stacey/Chris August Single (2015) 12:51:46 AM He Knows Your Name Denver & the Mile High Orches EP 12:55:16 AM More Than Conquerors Rend Collective The Art Of Celebration (2014) Praise & Worship from Moody Radio 04/28/15 Tuesday 1 A (CT) Air Time (CT) Title Artist Album 1:00:08 AM You Are My All In All Nichole Nordeman WOW Worship: Yellow (2003) 1:03:59 AM How Can It Be Lauren Daigle How Can It Be (2014) 1:08:12 AM Truth Calvin Nowell Start Somewhere 1:11:57 AM The One Aaron Shust Morning Rises (2013) 1:15:52 AM Great Is Thy Faithfulness Avalon Faith: A Hymns Collection (2006) 1:21:50 AM Beyond Me Toby Mac TBA (2015) 1:25:02 AM Jesus, You Are Beautiful Cece Winans Throne Room 1:29:53 AM No Turning Back Brandon Heath TBA (2015) 1:32:59 AM My God Point of Grace Steady On 1:37:28 AM Let Them See You JJ Weeks Band All Over The World (2009) 1:40:46 AM Yours Steven Curtis Chapman This Moment 1:45:28 AM Burn Bright Natalie Grant Hurricane (2013) 1:51:42 AM Indescribable Chris Tomlin Arriving (2004) 1:55:27 AM Made New Lincoln Brewster Oxygen (2014) Praise & Worship from Moody Radio 04/28/15 Tuesday 2 A (CT) Air Time (CT) Title Artist Album 2:00:09 AM Beautiful MercyMe The Generous Mr. -

The Parables of Jesus: Friendly Subversive Speech

The Parables of Jesus: Friendly Subversive Speech Introduction 4 Tell it Slant Typology and Parables The Four Gospels and Parables Messianic Consciousness Matthew’s Sermon of Parables 1 The Parable of the Sower 13 “Holy Seed” Isaiah’s Open Secret Jesus’ Interpretation Good-Soil Understanding 2 The Parable of the Weeds among the Wheat 22 Mustard Seeds and Yeast Echoes of Asaph Jesus’ Explanation 3 The Parables of the Hidden Treasure, the Pearl, and the Net 32 The Joy of the Gospel The Net New Treasures 4 The Parable of the Good Samaritan 37 Setting the Scene Augustine’s Allegory The Expert Who is my Neighbor? Messianic Edge 5 The Parable of the Friend at Midnight 50 Midnight Request Global Neighbors How Much More! 6 The Parable of the Rich Fool 55 Do We Practice What We Preach? The Meaning of Life All Kinds of Greed The Fool Jesus’ Hierarchy of Needs 7 The Parable of the Faithful Servants and the Exuberant Master 67 The Master is Coming! The Master Serves 8 The Parable of the Faithless Servant and the Furious Master 73 Managerial Responsibilities Managers of the Mysteries of God’s Revelation The Master’s Fury 1 9 The Parable of the Barren Fig Tree 80 Fig Tree Judgment Repentance Productivity 10 The Parable of the Great Banquet 86 The Narrow Door Jesus Will Not Be Managed Tension Around the Table Mundane Excuses The Host 11 The Parable of the Tower Builder and King at War 94 Christ-less Christianity Counting the Cost Who Among You? 12 The Parables of the Lost Sheep, the Lost Coin, and the Lost Sons 101 The Compassionate Father Prodigal -

BIBLE MEMORY VERSE ACTIVITIES “You Shall Love the Lord Your God with All Your Heart and with All Your Soul and with All Your Mind

Teacher’s Guide: Ages 8-9 Kings & Kingdoms Part 1: The Life of Jesus Unit 5, Lesson 25 The Vine and the Branches Lesson Aim: To understand what it means to remain in Jesus and bear fruit. THE WORSHIP Who God is: The King Who Teaches THE WORD Bible Story: John 15:1-8 What He has done: Jesus taught He is the Vine and we are the branches. Key Verse: John 15:4 THE WAY Christ Connection: Isaiah 27:3 BIBLE MEMORY VERSE “You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind… Love your neighbor as yourself.” Matthew 22:37, 39 Unit 5: The King Who Teaches—Parables 1 Bible Story What He Has Done Lesson Aim 23 The Lost Sheep, Jesus taught that God finds those To recognize we wander like Luke 15:4-7 who are lost. sheep and Jesus is our Shepherd. 24 The Sower, Jesus taught about four different To understand why some believe Luke 8:4-8, 11-15 responses to God’s Word. God’s Word and some do not. 25 The Vine and the Branches, Jesus taught He is the Vine and To understand what it means to John 15:1-8 we are the branches. remain in Jesus and bear fruit. 26 The Workers in the Vineyard, Jesus taught about a fair and To know God is fair and generous. Matthew 20:1-16 generous landowner. 27 The Great Banquet, Jesus taught about guests invited To see that we need to respond Luke 14:15-24 to a banquet. -

Luke's Parable of the Canny Steward

158 Luke’s Parable of the Canny Steward E Bruce Brooks University of Massachusetts at Amherst SEECR / University of North Carolina (31 Oct 2014) In the light of the Luke A/B/C formation model introduced in a previous study,1 I here consider what is usually called the Parable of the Unjust Steward (Lk 16:1-8), its context in Lk 15-16, and a possible, and less inscrutable, Chinese antecedent. Text. The Parable may be notably difficult,2 but its message is nonetheless obvious (be wise about the next world, just as worldlings are wise about this world, Lk 16:8b). There follow several comments on the parable: Lk 16:9, 10-12, and 13.3 The text goes: Lk 16:1. And he said also unto the disciples, There was a certain rich man who had a steward, and the same was accused unto him that he was wasting his goods. [2] And he called him and said unto him, What is this that I hear of thee? Render the account of thy stewardship; for thou canst be no longer steward. [3] And the steward said within himself, What shall I do, seeing that my lord taketh away the stewardship from me? I have not strength to dig; to beg I am ashamed. [4] I am resolved what to do, that, when I am put out of the stewardship, they may receive me into their houses. [5] And calling to him each one of his lord’s debtors, he said to the first, How much owest thou unto my lord? [6] And he said, A hundred measures of oil. -

The World's Largest Selection of Christian Songbooks!

19424 BrentBenBroch 9/25/07 10:09 AM Page 1 The world’s largest selection of Christian songbooks! Hal Leonard is proud to be the distributor for Nashville-based Brentwood-Benson. Their extensive catalog offers something for everyone – great new releases from the hottest CCM artists to traditional and contemporary gospel collection. This brochure features just a sampling of Brentwood-Benson’s outstanding artist collections, song compilations, and songbook series. All of these titles are in stock and ready for you to order! Contact your Hal Leonard sales representative to place your order and find out about our Brentwood-Benson special offer! Call the E-Z Order Line at 1-800-554-0626 Send a message to [email protected] or visit www.halleonard.com/dealers 19424 BrentBenBroch 9/25/07 10:09 AM Page 2 MIXED FOLIOS Amazing Wedding Songs Top 100 Praise and Worship Top 100 Praise & Worship Top 100 Southern Gospel 30 of the Most Requested Songs – Volume 2 Songbook Songbook BRENTWOOD-BENSON Songs for That Special Day This guitar chord songbook includes: Ah, Lord Guitar Chord Songbook Lyrics, chord symbols and guitar chord dia- Book/CD Pack God • Celebrate Jesus • Glorify Thy Name • Lyrics, chord symbols and guitar chord dia- grams for 100 classics, including: Because He Listening CD – 5 songs Great Is Thy Faithfulness • How Majestic Is grams for 100 songs, including: As the Deer • Lives • Daddy Sang Bass • Gettin’ Ready to ✦ Includes: Always • Ave Maria • Butterfly Your Name • In the Presence of Jehovah • My Come, Now Is the Time to Worship • I Could Leave This World • He Touched Me • In the Kisses • Canon in D • Endless Love • I Swear Savior, My God • Soon and Very Soon • Sing of Your Love Forever • Lord, I Lift Your Sweet By and By • I’ve Got That Old Time • Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring • Love Will Be Victory Chant • We Have Come into This Name on High • Open the Eyes of My Heart • Religion in My Heart • Just a Closer Walk with Our Home • Ode to Joy • The Keeper of the House • and many more! Rock of Ages • and dozens more. -

Grade 4 Lesson Plan / Fall Semester 2018

Grade 4 Lesson Plan / Fall Semester 2018 Sunday/ Liturgical Lessons Key Concept Gospel Reading/ Question of the Week Monday Color Big Question #1: Who is Jesus Christ? Sept. 16 Green Ch. 1: God’s God loves and cares for all Matthew 21:28-32 (parable of the two sons) Providence creation and has a plan. All God Why is it important to follow through on your wants us to know about Him is promises to others? contained in Sacred Scripture and Sacred Tradition. Sept. 23 Green Ch. 2: God is God is always faithful to his Matthew 21:33-43 (parable of the tenants) Faithful people. Sin is present in the What can you do in your week to help the love world because of human choice. of God grow in the world? Sept. 30 Green Ch. 3: God’s The Ten Commandments tell us Matthew 22:1-14 (the wedding banquet) What Commandments how to love God and others, three things can you do this week to show that and Unit Review God gave them to us to teach us you are a follower of Jesus? how to be faithful to him. Oct. 7 Green Ch. 4: In God’s Every person is worthy of Matthew 22:15-21 (paying taxes to the Image respect because they were emperor) Who needs help in your created in God’s image, they neighborhood or community? What could you each have a soul that will live and your family do to help? forever. Oct. 14 Green Ch. 5: Living in God created people for one Matthew 22:34-40 (the greatest Community another. -

Download Sample Pages

Lent (Year C) Making it Real and Relevant is published and distributed by LeaderResources P.O. Box 302 Leeds, MA 01053 www.LeaderResources.org 800‐941‐2218 [email protected] Copyright 2006‐2013 Heidi K. E. Hawks See Spirit Grow [email protected] This SAMPLER includes a small number of pages from this three‐year lectionary cycle curriculum (with summer sessions) When you purchase an annual license, all files are instantly‐downloadable both in Microsoft Word and Adobe PDF For more information or to speak to a representative call 800‐941‐2218 or visit www.LeaderResources.org LeaderResources Our ministry is helping you do you your ministry! Our resources are: • Practical and user friendly • Developed, tested and used in local congregations and diocese • Instantly downloadable and accessible to leaders 24/7 • Sold with a license to reproduce – print “as is” from the PDF file or use Microsoft Word to completely customize for your needs • Offered for a one‐time licensing fee or as an annual membership LeaderResources is a publishing and consulting group of Episcopal educators and clergy. WHAT YOU SHOULD KNOW ABOUT YOUR LIMITED‐USE LICENSE General Terms: This agreement covers all printed and electronic copies of this resource, including material downloaded from the LeaderResources website or obtained in any other manner. Licenses are normally issued to a church or other single‐entity, non‐profit organization. For information on multiple‐entity organizations (such as dioceses and other judicatories, national organizations with local subsidiaries, etc.) or a one‐time use license, please contact LeaderResources at the numbers below. Licenses are never issued to an individual person. -

The Authority of Jesus Questioned the Parable of the Two Sons

The Authority of Jesus Questioned 23 When he entered the temple, the chief priests and the elders of the people came to him as he was teaching, and said, “By what authority are you doing these things, and who gave you this authority?” 24 Jesus said to them, “I will also ask you one question; if you tell me the answer, then I will also tell you by what authority I do these things. 25 Did the baptism of John come from heaven, or was it of human origin?” And they argued with one another, “If we say, ‘From heaven,’ he will say to us, ‘Why then did you not believe him?’ 26 But if we say, ‘Of human origin,’ we are afraid of the crowd; for all regard John as a prophet.” 27 So they answered Jesus, “We do not know.” And he said to them, “Neither will I tell you by what authority I am doing these things. The Parable of the Two Sons 28 “What do you think? A man had two sons; he went to the first and said, ‘Son, go and work in the vineyard today.’ 29 He answered, ‘I will not’; but later he changed his mind and went. 30 The father[e] went to the second and said the same; and he answered, ‘I go, sir’; but he did not go. 31 Which of the two did the will of his father?” They said, “The first.” Jesus said to them, “Truly I tell you, the tax collectors and the prostitutes are going into the kingdom of God ahead of you. -

Pga01a36 Layout 1

Includes Family DVD section! Spring/Summer 2013 More Than 14,000 CDs and 210,000 Music Downloads Available at Christianbook.com! DVD— page A1 CD— CD— page 3 page 40 Christianbook.com 1–800–CHRISTIAN® New Releases THE BIBLE: MUSIC INSPIRED BY THE EPIC MINISERIES Table of Contents Discover songs that have been Accompaniment Tracks . .14, 15 inspired by the History Channel’s Bargains . .2, 38 epic miniseries! Includes “In Your Eyes” (Francesca Battis t elli); Collections . .4, 5, 7–9, 18–27, 33, 36, 37, 39 “Live Like That” (Sidewalk Proph - Contemporary & Pop . .28–31, back cover ets); “This Side of Heaven” (Chris August); “Love Come to Life” (Big Fitness Music DVDs . .21 Daddy Weave); “Crave” (For King Folios & Songbooks . .16, 17 & Country); “Home” (Dara MacLean); “Wash Me Away” (Point of Grace); “Starting Line” (Jason Castro); and more. Gifts . .back cover $ 00 Hymns . .24–27 WRCD88876 Retail $9.99 . .CBD Price 5 Inspirational . .12, 13 Instrumental . .22, 23 Kids’ Music . .18, 19 sher in the springtime season of renewal with Messianic . .10 Umusic and movies that will rejuvenate your spir- it! Filled with new items, bestsellers, and customer Movie DVDs . .A1–A36 favorites, these pages showcase great gifts to New Releases . .3–5, back cover treasure for yourself, as well as share with friends and family. And we offer our best prices possible— Praise & Worship . .6–9, back cover every day! Rock & Alternative . .32, 33, back cover Worship Jesus through song with new releases from Michael English (page 5) and Kari Jobe (back Scenic Music DVDs . .20 cover); keep on track with your healthy living goals Southern Gospel, Country & Bluegrass . -

Heritage&Festival Sat 10-19-19.Pub

19th Sunday after Pentecost ~ Sat., Oct. 19, 2019, 5 pm ~ Sun., Oct 20, 2019, 8:30 am “Sharing the Shepherd’s Love with All of God’s Children” Welcome to Worship! Gathering The Holy Spirit calls us together as the people of God. Pray always. Do not lose heart. This is the PRELUDE encouragement of the On the altar are the Holy Communion kits which are taken to our people who, for a variety of reasons cannot attend worship, to help them share in our celebration of the Lord’s Christ of the gospel Supper. today. Persistence in our every encounter with the WORDS OF WELCOME divine will be blessed. Wrestle with the word. ORDER FOR CONFESSION & FORGIVENESS Remember your baptism All may make the sign of the cross, the sign marked at baptism, as the presiding minister again and again. Come begins. regularly to Christ’s table. Persistence in our every Blessed be the holy Trinity, ☩ one God, encounter with the divine the strength of our ancestors, will be blessed. the host of this meal, the builder of the city that is to come. Amen. If we have died with Christ, we will also live with Christ. We confess our sin to the one who is faithful. Silence is kept for reflection. God our helper, we confess the many ways we have failed to live as your disciples. We have not finished what we began. We have feasted with friends but ignored strangers. We have been captivated by our possessions. Lift our burdens, gracious God. Refresh our hearts and forgive our sin.