The Parables of Jesus: Friendly Subversive Speech

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Miscellaneous Biblical Studies

MISCELLANEOUS BIBLICAL STUDIES Thomas F. McDaniel, Ph.D. © 2010 All Rights Reserved TABLE OF CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS iv I. SOME OBSERVATIONS ON GENDER AND SEXUALITY IN BIBLICAL TRADITION 1 II. WHY THE NAME OF GOD WAS INEFFABLE 72 III. ELIMINATING ‘THE ENEMIES OF THE LORD’ IN II SAMUEL 12:14 84 IV. RECONSIDERING THE ARABIC COGNATES WHICH CLARIFY PSALM 40:7 89 V. A NEW INTERPRETATION OF PROV 25:21–22 AND ROM 12:17–21 99 VI. ARABIC COGNATES HELP TO CLARIFY JEREMIAH 2:34b 107 VII. NOTES ON MATTHEW 6:34 “SUFFICIENT UNTO THE DAY IS THE EVIL THEREOF” 116 VIII. WHAT DID JESUS WRITE ACCORDING TO JOHN 8:6b–8? 127 IX. NOTES ON JOHN 19:39, 20:15 AND MATT 3:7 138 X. RECOVERING JESUS’ WORDS BY WHICH HE INITIATED THE EUCHARIST 151 XI. UNDERSTANDING SARAH’S LAUGHTER AND LYING: GENESIS 18:9–18 167 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS XII. REDEFINING THE eivkh/, r`aka,, AND mwre, IN MATTHEW 5:22 182 XIII. LUKE’S MISINTERPRETATION OF THE HEBREW QUOTATION IN ACTS 26:14 205 XIV. THE ORIGIN OF JESUS ’ “MESSIANIC SECRET” 219 XV. LOST LEXEMES CLARIFY MARK 1:41 AND JOHN 3:3–4 245 XVI. LOST LEXEMES CLARIFY JOHN 11:33 AND 11:38 256 XVII. A NEW INTERPRETATION OF JESUS’ CURSING THE FIG TREE 267 XVIII A NEW INTERPRETATION OF JESUS’ PARABLE OF THE WEDDING BANQUET 287 XIX RESTORING THE ORIGINAL VERSIFICATION OF ISAIAH 8 305 XX A BETTER INTERPRETATION OF ISAIAH 9:5–6a 315 XXI THE SEPTUAGINT HAS THE CORRECT TRANSLATION OF EXODUS 21:22–23 321 iii XXII RECOVERING THE WORDPLAY IN ZECHARIAH 2:4–9 [MT 2:8–13] 337 BIBLIOGRAPHY 348 iv ABBREVIATIONS A-text Codex Alexandrinus AB Anchor Bible, New York ABD The Anchor Bible Dictionary AJSL American Journal of Semitic Languages and Literature, Chicago AnBib Analecta Biblica, Rome AOS American Oriental Society, New Haven ATD Das Alte Testament Deutsch, Göttingen AV Authorized Version of the Bible, 1611 (same as KJV, 1611) B-text Codex Vaticanus BASOR Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, Philadelphia BCTP A Bible Commentary for Teaching and Preaching BDB F. -

The Bible in Outline

Mark 11:1-25 – The Messenger of the Covenant 1 As they approached Jerusalem and came to Bethphage and Bethany at the Mount of Olives, Jesus sent two of his disciples, 2 saying to them, “Go to the village ahead of you, and just as you enter it, you will find a colt tied there, which no-one has ever ridden. Untie it and bring it here. 3 If anyone asks you, „Why are you doing this?‟ tell him, „The Lord needs it and will send it back here shortly.‟ ” 4 They went and found a colt outside in the street, tied at a doorway. As they untied it, 5 some people standing there asked, “What are you doing, untying that colt?” 6 They answered as Jesus had told them to, and the people let them go. 7 When they brought the colt to Jesus and threw their cloaks over it, he sat on it. 8 Many people spread their cloaks on the road, while others spread branches they had cut in the fields. 9 Those who went ahead and those who followed shouted, “Hosanna!” “Blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord!” 10 “Blessed is the coming kingdom of our father David!” “Hosanna in the highest!” 11 Jesus entered Jerusalem and went to the temple. He looked around at everything, but since it was already late, he went out to Bethany with the Twelve. 12 The next day as they were leaving Bethany, Jesus was hungry. 13 Seeing in the distance a fig-tree in leaf, he went to find out if it had any fruit. -

“Thy Kingdom Come” – the Parables of Jesus

1 “Thy Kingdom Come” – The Parables of Jesus “Why do you speak to them in parables?” When we think of the ministry of Jesus, we probably think of great miracles & small moments of grace. We think of shared meals, healed bodies, & grateful, forgiven hearts. We probably think of parables too. Jesus taught his disciples & the crowds that followed him in both actions & words. Sometimes he spoke in simple statements – “Blessed are the poor” - & at other times he issued warnings. Stern ones too, mostly to religious leaders: “Woe to you Pharisees…” On many other occasions he told stories. Not just any kind of stories, not anecdotes, epics or fables. What Jesus told were parables. The English word “parable” is a translation of the Hebrew term mashal. It is not entirely clear what this word meant in its original culture setting but it may have had a link with Jewish prophecy. Prophetic knowledge comes from a visionary experience & this can only partly be expressed in normal language. A mashal involves analogy, where one thing is said to be “related” to another thing. In Greek, the word parable comes from a word that means “comparison.” We call Jesus’ stories parables because they invite us to see a comparison: between the kingdom of God & a banquet, between God & a landowner, between ourselves &… which are we, anyway? The Pharisee or the tax-collector? The older son or the younger? The bridesmaids who are prepared or those who are caught short? The workers who toil all day or the latecomers? If you are already familiar with these parables, your answer to those questions might well be different today than it was 5 or 10 years ago. -

Complete Stories by Franz Kafka

The Complete Stories by Franz Kafka Back Cover: "An important book, valuable in itself and absolutely fascinating. The stories are dreamlike, allegorical, symbolic, parabolic, grotesque, ritualistic, nasty, lucent, extremely personal, ghoulishly detached, exquisitely comic. numinous and prophetic." -- New York Times "The Complete Stories is an encyclopedia of our insecurities and our brave attempts to oppose them." -- Anatole Broyard Franz Kafka wrote continuously and furiously throughout his short and intensely lived life, but only allowed a fraction of his work to be published during his lifetime. Shortly before his death at the age of forty, he instructed Max Brod, his friend and literary executor, to burn all his remaining works of fiction. Fortunately, Brod disobeyed. The Complete Stories brings together all of Kafka's stories, from the classic tales such as "The Metamorphosis," "In the Penal Colony" and "The Hunger Artist" to less-known, shorter pieces and fragments Brod released after Kafka's death; with the exception of his three novels, the whole of Kafka's narrative work is included in this volume. The remarkable depth and breadth of his brilliant and probing imagination become even more evident when these stories are seen as a whole. This edition also features a fascinating introduction by John Updike, a chronology of Kafka's life, and a selected bibliography of critical writings about Kafka. Copyright © 1971 by Schocken Books Inc. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Schocken Books Inc., New York. Distributed by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York. The foreword by John Updike was originally published in The New Yorker. -

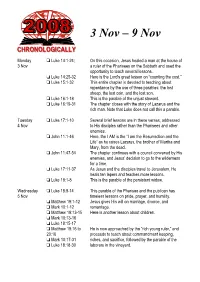

Monday 3 Nov Tuesday 4 Nov Wednesday 5 Nov Luke 14:1-24

Monday Luke 14:1-24; On this occasion, Jesus healed a man at the house of 3 Nov a ruler of the Pharisees on the Sabbath and used the opportunity to teach several lessons. Luke 14:25-32 Here is the Lord's great lesson on “counting the cost.” Luke 15:1-32 This entire chapter is devoted to teaching about repentance by the use of three parables: the lost sheep, the lost coin, and the lost son. Luke 16:1-18 This is the parable of the unjust steward. Luke 16:19-31 The chapter closes with the story of Lazarus and the rich man. Note that Luke does not call this a parable. Tuesday Luke 17:1-10 Several brief lessons are in these verses, addressed 4 Nov to His disciples rather than the Pharisees and other enemies. John 11:1-46 Here, the I AM is the “I am the Resurrection and the Life” as he raises Lazarus, the brother of Martha and Mary, from the dead. John 11:47-54 The chapter continues with a council convened by His enemies, and Jesus' decision to go to the wilderness for a time. Luke 17:11-37 As Jesus and the disciples travel to Jerusalem, He heals ten lepers and teaches more lessons. Luke 18:1-8 This is the parable of the persistent widow. Wednesday Luke 18:9-14 This parable of the Pharisee and the publican has 5 Nov timeless lessons on pride, prayer, and humility. Matthew 19:1-12 Jesus gives His will on marriage, divorce, and Mark 10:1-12 remarriage. -

The Parables of Jesus

THE NEW TESTAMENT PARABLES OF JESUS Year 1– Quarter 4 by F. L. Booth ©2005 F. L. Booth Zion, IL 60099 CONTENTS PAGE PREFACE CHART NO. 1 - Parables of Jesus in Chronological Order CHART NO. 2 - Classification of the Parables of Jesus LESSON 1 - Parables of the Kingdom No. 1 The Parable of the Sower 1 - 1 LESSON 2 - Parables of the Kingdom No. 2 I. The Parable of the Tares 2 - 1 II. The Parable of the Seed Growing in Secret 2 - 3 III. The Parable of the Mustard Seed 2 - 5 IV. The Parable of the Leaven 2 - 7 LESSON 3 - Parables of the Kingdom No. 3 I. The Parable of the Hidden Treasure 3 - 1 II. The Parable of the Pearl of Great Price 3 - 3 III. The Parable of the Drawnet 3 - 5 IV. The Parable of the Laborers in the Vineyard 3 - 7 LESSON 4 - Parables of Forgiveness I. The Parable of the Two Debtors 4 - 1 II. The Parable of the Unmerciful Servant 4 - 5 LESSON 5 - A Parable of the Love of One's Neighbor The Parable of the Good Samaritan 5 - 1 A Parable of Jews and Gentiles The Parable of the Wicked Husbandmen 5 - 4 LESSON 6 - Parables of Praying I. The Parable of the Friend at Midnight 6 - 1 II. The Parable of the Importunate Widow 6 - 3 LESSON 7 - Parables of Self-Righteousness and Humility I. The Parable of the Chief Seats 7 - 1 II. The Parable of the Pharisee and the Publican 7 - 3 LESSON 8 - Parables of the Cost of Discipleship I. -

Preaching and Teaching the Parables of Jesus Stephen J

Editorial: Preaching and Teaching the Parables of Jesus Stephen J. Wellum ent Hughes begins his book on Mark’s sion of soul and of spirit, of joints and of marrow, K Gospel recounting what happened to E. V. and discerning the thoughts and intentions of the Rieu, one of the world’s famous scholars of the clas- heart” (4:12, ESV). sics, a number of years ago. After having completed In fact, it is precisely because Scripture is what a translation of Homer into modern English for the it is, namely God’s Word written, and that it is by Penguin Classics series, he was then asked by the his Word that our Triune God discloses himself publisher to translate the Gospels. At this time in to us, convicts us of our sin, and conforms us to his life, Rieu was sixty years old and a self-avowed the image of the Son, that every year SBJT devotes agnostic all his life. Hughes recounts that when one issue to the specific book or portion of Scrip- Rieu’s son heard what his father ture which corresponds to Lifeway’s January Bible Stephen J. Wellum is Professor of Christian Theology at The South- was about to do, he said, “It will Study. We do so not merely to increase our knowl- ern Baptist Theological Seminary. be interesting to see what Father edge of the Scripture—as important as that is— will make of the four Gospels. It but also more significantly to bring our thought Dr. Wellum received his Ph.D. -

Mark 11:20-33 ~ Scripture Verses

Mark 11:20-33 ~ Scripture Verses The Withered Fig Tree 12 The next day as they were leaving Bethany, Jesus was hungry. 13 Seeing in the distance a fig tree in leaf, he went to find out if it had any fruit. When he reached it, he found nothing but leaves, because it was not the season for figs. 14 Then he said to the tree, “May no one ever eat fruit from you again.” And his disciples heard him say it. [Verses 15 to 19: Jesus clears the temple] 20 In the morning, as they went along, they saw the fig tree withered from the roots. 21 Peter remembered and said to Jesus, “Rabbi, look! The fig tree you cursed has withered!” 22 “Have [a] faith in God,” Jesus answered. 23 “I tell you the truth, if anyone says to this mountain, ‘Go, throw yourself into the sea,’ and does not doubt in his heart but believes that what he says will happen, it will be done for him. 24 Therefore I tell you, whatever you ask for in prayer, believe that you have received it, and it will be yours. 25 And when you stand praying, if you hold anything against anyone, forgive him, so that your Father in heaven may forgive you your sins.[b]” The Authority of Jesus Questioned 27 They arrived again in Jerusalem, and while Jesus was walking in the temple courts, the chief priests, the teachers of the law and the elders came to him. 28 “By what authority are you doing these things?” they asked. -

The Parables of Jesus Is That We Know the Punchline to the Stories (I.E

Sponsored by ENROLL occ.edu/admissions ONLINE COURSES occ.edu/online GIVE occ.edu/donate SESSION 1 -One of the problems with studying the parables of Jesus is that we know the punchline to the stories (i.e. we know how they end). -In this lesson we tell three stories outside of the Gospels to help us prepare for the study of the parables of Jesus. Three stories: # 1: Story of the Jewish tailor—there is such a thing as an enigmatic ending! Story leaves you wanting more! # 2: Story of the needy family with student in the signature group, “Impact Brass and Singers.” Story of the bad guy being the good guy! # 3: Story of the broken car and helping female faculty member by biker. Story of wrong perceptions and leaving open-ended. -Enigma, bad guys doing well, and wrong perceptions and open-ended are all characteristics of Jesus’ parables. SESSION 2 Resources -Kenneth Bailey says that Jesus was a “metaphoric theologian.” Well, if that’s true we are probably going to need some help understanding him because metaphor, symbolism and analogies are not always easy to interpret. Resources (from most significant to lesser significant): 1) Klyne Snodgrass, Stories with Intent. 2) Kenneth Bailey, Through Peasant Eyes, Poet and Peasant, and Jesus through Middle Easter Eyes. 3) Gary Burge, Jesus the Storyteller. 4) Craig Blomberg, Interpreting the Parables. 5) Craig Blomberg, Preaching the Parables. 6) Roy Clements, A Sting in the Tale. 7) C.H. Dodd, The Parables of the Kingdom. 8) William Herzog, The Parables as Subversive Speech. -

Quaker Higher Education QHE a Publication of the Friends Association for Higher Education

Quaker Higher Education QHE A Publication of the Friends Association for Higher Education Volume 9: Issue 2 November, 2015 What is the careful work that we as testimony of integrity and truth-telling, educators, artists and scholars must do to to the secular task of investigating crime. foster “Aha!” moments and perspective From Earlham College, Kelly Burk, shifts for our students, publics, and Director of Religious Life, and Trish colleagues? How do we draw on the Eckert, Director of the Newlin Quaker grace of language in poetry, theatre, and Center, carefully outline the steps and song, as well as the tools of consensus, resources that they and their students forensics, and Biblical exegesis to take have found useful when speaking one’s on tough conversations, realities and truth, listening to others’ truth, and truths? The six essays and works of this moving forward in (very) difficult Fall 2016 issue of Quaker Higher conversations. Education help us address these queries. Stephen Pothoff, associate professor of Bill Jolliff, poet and professor of English religion and philosophy at Wilmington at George Fox University, shares with us College, walks us carefully through the his keynote address to 2015 June’s confounding Markan account of Jesus FAHE conferees. He provides cursing the fig tree. His Biblical and guideposts for enjoying and growing historical “forensics” reveal how Jesus from contemporary poetry that offer was speaking truth to imperial Rome. delight, identification, transcendence, and epiphany. Finally, we present The Healing Blues Project, a multimedia engagement with Darlene R. Graves, Professor of Digital homelessness, co-created by Ted Media and Communication Arts at Efremoff, assistant professor of Digital Liberty University, takes us beyond the Photography and Video Art at Central Friends’ historical aversion to the “lively Connecticut State University. -

Prayer Or Despair? the Parables of the Friend at Midnight and the Unjust Judge

PRAYER OR DESPAIR? THE PARABLES OF THE FRIEND AT MIDNIGHT AND THE UNJUST JUDGE By Ronald A. Julian An Integrative Thesis Submitted To The Faculty of Reformed Theological Seminary In Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree Master of Arts THESIS ADVISOR: ________________________________ Dr. Simon Kistemaker RTS/VIRTUAL PRESIDENT ________________________________ Dr. Andrew J. Peterson September 2006 ii CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ........................................................................................................ v LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS.................................................................................................. vi Chapter 1. INTRODUCTION......................................................................................................1 2. METHODOLOGY.....................................................................................................3 The Interpretation of Parables............................................................................3 Higher Criticism.................................................................................................4 3. THE PARABLE OF THE FRIEND AT MIDNIGHT ...............................................8 Background and Context....................................................................................9 Exegetical Details in the Story.........................................................................12 The Meaning of the Parable.............................................................................22 4. THE PARABLE OF -

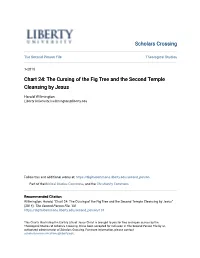

The Cursing of the Fig Tree and the Second Temple Cleansing by Jesus

Scholars Crossing The Second Person File Theological Studies 1-2018 Chart 24: The Cursing of the Fig Tree and the Second Temple Cleansing by Jesus Harold Willmington Liberty University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/second_person Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, and the Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Willmington, Harold, "Chart 24: The Cursing of the Fig Tree and the Second Temple Cleansing by Jesus" (2018). The Second Person File. 131. https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/second_person/131 This Charts Illustrating the Earthly Life of Jesus Christ is brought to you for free and open access by the Theological Studies at Scholars Crossing. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Second Person File by an authorized administrator of Scholars Crossing. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Earthly Ministry of Jesus Chart 24 THE FIG TREE & THE 2ND CLEANSING MONDAY: JESUS CURSING THE FIG TREE The Reason For The Fig Tree Visit 18Now in the morning as he returned into the city, he hungered. (Mt. 21:18) The Reaction During The Fig Tree Visit • What Jesus Discovered: 13And seeing a 9ig tree afar off having leaves, he came, if haply he might 9ind any thing thereon: and when he came to it, he found nothing but leaves; for the time of 9igs was not yet. (Mk. 11:13) • What Jesus Did: 14And Jesus answered and said unto it, No man eat fruit of thee hereafter for ever. And his disciples heard it. (Mk. 11:14) The Results From The Fig Tree Visit • The Amazement Of The Apostles: 20And when the disciples saw it, they marvelled, saying, How soon is the 9ig tree withered away! (Mt.