“Thy Kingdom Come” – the Parables of Jesus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Parables of Jesus

THE NEW TESTAMENT PARABLES OF JESUS Year 1– Quarter 4 by F. L. Booth ©2005 F. L. Booth Zion, IL 60099 CONTENTS PAGE PREFACE CHART NO. 1 - Parables of Jesus in Chronological Order CHART NO. 2 - Classification of the Parables of Jesus LESSON 1 - Parables of the Kingdom No. 1 The Parable of the Sower 1 - 1 LESSON 2 - Parables of the Kingdom No. 2 I. The Parable of the Tares 2 - 1 II. The Parable of the Seed Growing in Secret 2 - 3 III. The Parable of the Mustard Seed 2 - 5 IV. The Parable of the Leaven 2 - 7 LESSON 3 - Parables of the Kingdom No. 3 I. The Parable of the Hidden Treasure 3 - 1 II. The Parable of the Pearl of Great Price 3 - 3 III. The Parable of the Drawnet 3 - 5 IV. The Parable of the Laborers in the Vineyard 3 - 7 LESSON 4 - Parables of Forgiveness I. The Parable of the Two Debtors 4 - 1 II. The Parable of the Unmerciful Servant 4 - 5 LESSON 5 - A Parable of the Love of One's Neighbor The Parable of the Good Samaritan 5 - 1 A Parable of Jews and Gentiles The Parable of the Wicked Husbandmen 5 - 4 LESSON 6 - Parables of Praying I. The Parable of the Friend at Midnight 6 - 1 II. The Parable of the Importunate Widow 6 - 3 LESSON 7 - Parables of Self-Righteousness and Humility I. The Parable of the Chief Seats 7 - 1 II. The Parable of the Pharisee and the Publican 7 - 3 LESSON 8 - Parables of the Cost of Discipleship I. -

Preaching and Teaching the Parables of Jesus Stephen J

Editorial: Preaching and Teaching the Parables of Jesus Stephen J. Wellum ent Hughes begins his book on Mark’s sion of soul and of spirit, of joints and of marrow, K Gospel recounting what happened to E. V. and discerning the thoughts and intentions of the Rieu, one of the world’s famous scholars of the clas- heart” (4:12, ESV). sics, a number of years ago. After having completed In fact, it is precisely because Scripture is what a translation of Homer into modern English for the it is, namely God’s Word written, and that it is by Penguin Classics series, he was then asked by the his Word that our Triune God discloses himself publisher to translate the Gospels. At this time in to us, convicts us of our sin, and conforms us to his life, Rieu was sixty years old and a self-avowed the image of the Son, that every year SBJT devotes agnostic all his life. Hughes recounts that when one issue to the specific book or portion of Scrip- Rieu’s son heard what his father ture which corresponds to Lifeway’s January Bible Stephen J. Wellum is Professor of Christian Theology at The South- was about to do, he said, “It will Study. We do so not merely to increase our knowl- ern Baptist Theological Seminary. be interesting to see what Father edge of the Scripture—as important as that is— will make of the four Gospels. It but also more significantly to bring our thought Dr. Wellum received his Ph.D. -

The Parables of Jesus Is That We Know the Punchline to the Stories (I.E

Sponsored by ENROLL occ.edu/admissions ONLINE COURSES occ.edu/online GIVE occ.edu/donate SESSION 1 -One of the problems with studying the parables of Jesus is that we know the punchline to the stories (i.e. we know how they end). -In this lesson we tell three stories outside of the Gospels to help us prepare for the study of the parables of Jesus. Three stories: # 1: Story of the Jewish tailor—there is such a thing as an enigmatic ending! Story leaves you wanting more! # 2: Story of the needy family with student in the signature group, “Impact Brass and Singers.” Story of the bad guy being the good guy! # 3: Story of the broken car and helping female faculty member by biker. Story of wrong perceptions and leaving open-ended. -Enigma, bad guys doing well, and wrong perceptions and open-ended are all characteristics of Jesus’ parables. SESSION 2 Resources -Kenneth Bailey says that Jesus was a “metaphoric theologian.” Well, if that’s true we are probably going to need some help understanding him because metaphor, symbolism and analogies are not always easy to interpret. Resources (from most significant to lesser significant): 1) Klyne Snodgrass, Stories with Intent. 2) Kenneth Bailey, Through Peasant Eyes, Poet and Peasant, and Jesus through Middle Easter Eyes. 3) Gary Burge, Jesus the Storyteller. 4) Craig Blomberg, Interpreting the Parables. 5) Craig Blomberg, Preaching the Parables. 6) Roy Clements, A Sting in the Tale. 7) C.H. Dodd, The Parables of the Kingdom. 8) William Herzog, The Parables as Subversive Speech. -

The Parables of Jesus: Friendly Subversive Speech

The Parables of Jesus: Friendly Subversive Speech Introduction 4 Tell it Slant Typology and Parables The Four Gospels and Parables Messianic Consciousness Matthew’s Sermon of Parables 1 The Parable of the Sower 13 “Holy Seed” Isaiah’s Open Secret Jesus’ Interpretation Good-Soil Understanding 2 The Parable of the Weeds among the Wheat 22 Mustard Seeds and Yeast Echoes of Asaph Jesus’ Explanation 3 The Parables of the Hidden Treasure, the Pearl, and the Net 32 The Joy of the Gospel The Net New Treasures 4 The Parable of the Good Samaritan 37 Setting the Scene Augustine’s Allegory The Expert Who is my Neighbor? Messianic Edge 5 The Parable of the Friend at Midnight 50 Midnight Request Global Neighbors How Much More! 6 The Parable of the Rich Fool 55 Do We Practice What We Preach? The Meaning of Life All Kinds of Greed The Fool Jesus’ Hierarchy of Needs 7 The Parable of the Faithful Servants and the Exuberant Master 67 The Master is Coming! The Master Serves 8 The Parable of the Faithless Servant and the Furious Master 73 Managerial Responsibilities Managers of the Mysteries of God’s Revelation The Master’s Fury 1 9 The Parable of the Barren Fig Tree 80 Fig Tree Judgment Repentance Productivity 10 The Parable of the Great Banquet 86 The Narrow Door Jesus Will Not Be Managed Tension Around the Table Mundane Excuses The Host 11 The Parable of the Tower Builder and King at War 94 Christ-less Christianity Counting the Cost Who Among You? 12 The Parables of the Lost Sheep, the Lost Coin, and the Lost Sons 101 The Compassionate Father Prodigal -

The Parables of Jesus

F The Parables of Jesus The Camp Hill Church of Christ 3042 Cumberland Blvd. Camp Hill, PA 17011 1-717-737-5587 Introduction The parables of Jesus are among the most beloved of all stories in the Bible, or ever told. Unique in approach, these simple and colorful stories were effective, because they played to the everyday experiences of people, with poignant endings that brought the message home powerfully. Jesus' parables were often surprising and paradoxical. Someone once said that listening to Jesus tell a parable must have been a little like watching someone throw a ball into the air. Instead of reaching its apex and returning directly to earth, this particular ball starts back down and then veers off at a right angle. We watch astonished, and search for answers. Today, a detailed study of the parables can benefit us as well, as we search for our own answers. It is my intention to organize the material into a traditional 13 week format. However, there is much more than can be covered in this time period. There are over 40 parables and parabolic sayings covered in this outline, and that is not exhaustive. I encourage students of the Gospel to study the parables in depth on their own time. This is simply a study tool – let God’s word be your guide. Acknowledgements I wish to thank Brother Paul Cantrell for suggesting the approach for categorizing the parables, and for encouraging me to compile this study guide. Many thoughts were gleaned from “The Parables – Understanding the Stories Jesus Told” by Simon J. -

The Parables of Jesus: Better Than Fiction

Winter 2018 Book 1 The Parables of Jesus: Better Than Fiction Home Bible Studies Evangelical Free Church of Green Valley Coordinated with messages by Pastor Steve LoVellette Lessons prepared by Dave McCracken ii Introduction The parables of Jesus can be found in all the gospels, except for John, and in some of the non-canonical gospels, but are located mainly within the three Synoptic Gospels. They represent a main part of the teachings of Jesus, forming approximately one third of his recorded teachings. Bible scholar Madeline Boucher writes: The importance of the parables can hardly be overestimated. They comprise a substantial part of the recorded preaching of Jesus. The parables are generally regarded by scholars as among the sayings which we can confidently ascribe to the historical Jesus; they are, for the most part, authentic words of Jesus. Moreover, all of the great themes of Jesus' preaching are struck in the parables. Parables are not fables, not myths, not proverbs, not allegories. Jesus' parables are short stories that teach a moral or spiritual lesson by analogy or similarity. They are often stories based on the agricultural life that was intimately familiar to His original first century audience. It is the lesson of a parable that is important to us. The story is not important in itself; it may or may not be literally true. Jesus was the master of teaching in parables. His parables often have an unexpected twist or surprise ending that catches the reader's attention. They are also cleverly designed to draw listeners into new ways of thinking, new attitudes and new ways of acting. -

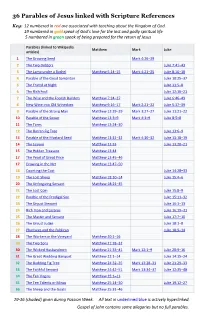

36 Parables of Jesus Linked with Scripture References

36 Parables of Jesus linked with Scripture References Key: 12 numbered in red are associated with teaching about the Kingdom of God 19 numbered in gold speak of God’s love for the lost and godly spiritual life 5 numbered in green speak of being prepared for the return of Jesus Parables (linked to Wikipedia Matthew Mark Luke articles) 1 The Growing Seed Mark 4:26–29 2 The Two Debtors Luke 7:41–43 3 The Lamp under a Bushel Matthew 5:14–15 Mark 4:21–25 Luke 8:16–18 4 Parable of the Good Samaritan Luke 10:25–37 5 The Friend at Night Luke 11:5–8 6 The Rich Fool Luke 12:16–21 7 The Wise and the Foolish Builders Matthew 7:24–27 Luke 6:46–49 8 New Wine into Old Wineskins Matthew 9:16–17 Mark 2:21–22 Luke 5:37–39 9 Parable of the Strong Man Matthew 12:29–29 Mark 3:27–27 Luke 11:21–22 10 Parable of the Sower Matthew 13:3–9 Mark 4:3–9 Luke 8:5–8 11 The Tares Matthew 13:24–30 12 The Barren Fig Tree Luke 13:6–9 13 Parable of the Mustard Seed Matthew 13:31–32 Mark 4:30–32 Luke 13:18–19 14 The Leaven Matthew 13:33 Luke 13:20 21 – 15 The Hidden Treasure Matthew 13:44 17 The Pearl of Great Price Matthew 13:45–46 17 Drawing in the Net Matthew 13:47–50 18 Counting the Cost Luke 14:28–33 19 The Lost Sheep Matthew 18:10–14 Luke 15:4–6 20 The Unforgiving Servant Matthew 18:21–35 21 The Lost Coin Luke 15:8–9 22 Parable of the Prodigal Son Luke 15:11–32 23 The Unjust Steward Luke 16:1–13 24 Rich man and Lazarus Luke 16:19–31 25 The Master and Servant Luke 17:7–10 26 The Unjust Judge Luke 18:1–8 27 Pharisees and the Publican Luke 18:9–14 28 The Workers in the Vineyard Matthew 20:1–16 29 The Two Sons Matthew 21:28–32 30 The Wicked Husbandmen Matthew 21:33–41 Mark 12:1–9 Luke 20:9–16 31 The Great Wedding Banquet Matthew 22:1–14 Luke 14:15–24 32 The Budding Fig Tree Matthew 24:32–35 Mark 13:28–31 Luke 21:29–33 33 The Faithful Servant Matthew 24:42–51 Mark 13:34–37 Luke 12:35–48 34 The Ten Virgins Matthew 25:1–13 35 The Ten Talents or Minas Matthew 25:14–30 Luke 19:12–27 36 The Sheep and the Goats Matthew 25:31 46 – 29-36 (shaded) given during Passion Week. -

Once Upon a Parable – the Good Shepherd (November 24, 2019)

Once upon a Parable – The Good Shepherd (November 24, 2019) This message was delivered in 3 parts. Big God Question – Why are you here today? The theme for today’s service is “The Lord is my Shepherd.” We will be looking at this theme by exploring 2 of Jesus’ parables about sheep and shepherds – one from the gospel of Matthew and one from the gospel of John. We will be asking ourselves 3 questions - Why are you here today? Who needs a shepherd anyway? Where is our hope? Some of you may be wondering why the first question is ‘why are you here today?’ First of all, this isn’t exactly the normal way of being greeted in a church! Usually, at this time in the worship service, I welcome everyone, tell you what’s going on in the life of the congregation, and then invite you for fellowship after the service. That’s my normal routine, but not today. The second reason why this question is strange is because you would think that it is obvious why we are all here today! But is it? There are many reasons why people go to church… Some of you have been attending this church for 50 years or more – and you have sat in the same pew all of that time! It is part of your family’s heritage and tradition. It is part of your DNA and when you walk into this building, you feel at home. Some of you started attending Knox since I came here 6 years ago. -

The Interpretation of Parables

Grace Theological Journal 11.2 (1970) 3-20 Copyright © 1970 by Grace Theological Seminary. Cited with permission. THE INTERPRETATION OF PARABLES VERNON D. DOERKSEN Assistant Professor of Theology and New Testament Arizona Bible College The striking importance of the parabolic method of teaching in Jewish thinking can be seen from this passage in the Apocrypha: But he that giveth his mind to the law of the most High, and is occupied in the meditation thereof, will seek out the wisdom of all the ancient, and be occupied in prophecies. He will keep the sayings of the renowned men: and where subtil parab1es are, he will be there also. He will seek out the secrets of grave sentences, and be conversant in dark parables (Eccles. 39:1-3). Our Lord made ready use of the parabolic method of teaching to the extent that Mark comments "but without a parable spake he not unto them" (4:34). The parables are not mere human tales; they are teachings of the Son of God, the One to whom the crowd listened gladly (Mk. 12:37). Of Him it is declared, "...the people were astonished at his doctrine: for he taught them as one having authority, and not as the scribes" (Matt. 7:28, 29). Of the parables, Armstrong writes: Indeed, they are sparks from that fire which our Lord brought to the earth (Lk. xii. 49)--the message of One who was 'a prophet...and more than a prophet' (Mk. xi.9; Lk. vii. 16)1 Christ's parables are not of mere man. -

The Parables of Jesus

4. The Kingdom of God equals ____________________. S TORIES THAT CHANGED THE WORLD Th e P a r a b le s o f J e s u s The kingdom of God is so valuable that it is worth losing everything on earth. PARABLES OF THE HIDDEN TREASURE AND FOUND PEARL Philippians 3:7-8 (ESV) “Indeed, I count everything as MATTHEW 13:44-46 loss because of the surpassing worth of knowing Christ Jesus my Lord. For his sake I have suffered the loss of all The Kingdom of God is God’s _____________ in your things and count them as rubbish, in order that I may gain life. Christ.” Romans 14:17 "for the kingdom of God is not eating and Romans 8:32 "He who did not spare His own Son, but drinking, but righteousness and peace and joy in the Holy delivered Him up for us all, how shall He not with Him Spirit." also freely give us all things?" 1. God’s reign is _______________ and personal. LESSONS FROM THE LORD When you surrender your life to the Kingly 1. Understand the ________________ of the Kingdom. rule of God through Jesus Christ, you are personally, here and now, in the Kingdom of God. 2. The Kingdom involves _____________________. Luke 14:28-33 "For which of you, intending to build a tower, does not sit down first and count the cost, whether he has enough to finish it... So likewise, whoever of you 2. God’s reign is ____________ and universal. does not forsake all that he has cannot be My disciple." 3. -

Parables These Guides Integrate Bible Study, Prayer, and Worship to Help Us Explore How Jesus’ Parables Lead Us to Know God’S Love and Loving Demands on Our Lives

Study Guides for Parables These guides integrate Bible study, prayer, and worship to help us explore how Jesus’ parables lead us to know God’s love and loving demands on our lives. Use them individually or in a series. You may Christian Reflection reproduce them for personal or group use. A Series in Faith and Ethics The Contexts of Jesus’ Parables 2 Jesus’ parables were created and preserved in conversation with both Jewish and Greco-Roman cultural environments, and they partake, vigorously at times, in those cultural dia- logues. As we become more aware of these diverse webs of meaning, we can respond more fully to the message of the one who spoke parables with one ear already listening for our responses. Hearing a Parable with the Early Church 4 What would it mean to hear Jesus’ parables in their final literary form in the Greco-Roman world? Perhaps we too hastily have stripped away the allegorizing of the early and medieval church as secondary embellishments that lead us away from the “original” message of Jesus. Hearing is Believing 6 Jesus’ parables cannot be understood by standing apart from them with arms folded in neutral objectivity. They can only be understood by “entering” into them, allowing their stories to lay claim on us. How do we drop our guard so parables may have their intended effect? Violent Parables with the Nonviolent Jesus 8 Jesus’ Sermon on the Mount instructs us to not return vio- lence for violence; instead, we should be like God, who offers boundless, gratuitous love to all. -

The Precious & Powerful Parables of Jesus Christ

1 THE PRECIOUS & POWERFUL PARABLES OF JESUS CHRIST (keep it simple) Student Outline A teacher with authority Luke tells us that people were astonished at Jesus's teaching because He taught like someone with authority. This is particularly impressive when you consider the fact that Jesus's teachings and stories were so simple. We often have the mistaken view that the more intelligent and complex an idea sounds, the more impressive it is. Jesus didn't see it that way. The parables of Jesus made the wisdom of God accessible. His teaching wasn't pretentious or unnecessarily complicated. And because of that, Jesus made the kingdom of God attainable for everyone. When people talk about the ministry of Jesus, it's easy to focus on his miracles. Jesus performed some amazing feats that the world had never seen (and hasn’t seen since). But one of the most exciting things about His ministry was His teaching style. Jesus taught using parables—simple stories intended to impart a spiritual lesson. He's so identified with this teaching style that Mark's Gospel tells us that "He did not say anything to them without using a parable" (Mark 4:34a). Fables versus Parables: Fable is a short story—usually with animals as the main characters—that conveys a moral. ... Parable is a short story that teaches a moral or spiritual lesson. Like fable, the parable also tells a simple story. But, whereas fables tend to personify animal characters—often giving the same impression as does an animated cartoon—the typical parable uses human agents.