The Trilogy of Parables in Mt 21:28-22:14 from a Matthean Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE PASSION of OUR LORD JESUS CHRIST Matthew 26:14-16, 30-27:66

SCRIPTURE READINGS FOR PALM/PASSION SUNDAY, April 5, 2020 Trinity Lutheran Church, Portland, Oregon THE ENTRY GOSPEL + Matthew 21:1-9 When they had come near Jerusalem and had reached Bethphage, at the Mount of Olives, Jesus sent two disciples, 2 saying to them, “Go into the village ahead of you, and immediately you will find a donkey tied, and a colt with her; untie them and bring them to me. 3 If anyone says anything to you, just say this, ‘The Lord needs them.’ And he will send them immediately.” 4 This took place to fulfill what had been spoken through the prophet, saying, 5 “Tell the daughter of Zion, Look, your king is coming to you, humble, and mounted on a donkey, and on a colt, the foal of a donkey.” 6 The disciples went and did as Jesus had directed them; 7 they brought the donkey and the colt, and put their cloaks on them, and he sat on them. 8 A very large crowd spread their cloaks on the road, and others cut branches from the trees and spread them on the road. 9 The crowds that went ahead of him and that followed were shouting, “Hosanna to the Son of David! Blessed is the one who comes in the name of the Lord! Hosanna in the highest heaven!” The Gospel of the Lord. Thanks be to God. THE PASSION OF OUR LORD JESUS CHRIST Matthew 26:14-16, 30-27:66 One of the twelve, whose name was Judas Iscariot, went to the chief priests 15and said, "What will you give me if I deliver him over to you?" And they paid him thirty pieces of silver.16And from that moment he sought an opportunity to betray him…. -

I.H. Marshall, Eschatology and the Parables. London

Eschatology and the Parables By I. Howard Marshall This lecture was delivered in Cambridge on 6 July, 1963 at a meeting convened by the Tyndale Fellowship for Biblical Research [p.5] In any attempt to understand the teaching of Jesus as recorded in the Synoptic Gospels, a consideration of the parables must take an important place. This is demonstrated not merely by the plethora of critical study and popular exposition to which the parables have given rise,1 but above all by the place which the parables occupy in the Synoptic tradition. According to A. M. Hunter roughly one third of the recorded teaching of Jesus consists of parables and parabolic statements.2 There are some forty parables and twenty parabolic statements (to say nothing of the many metaphorical statements) in the teaching of Jesus, and they are found in all of the four sources or collections of material commonly distinguished by students of the Gospels.3 Further, there is abundant evidence of Palestinian background and Semitic speech in the parables. So sceptical a critic as R. Bultmann can say that ‘the main part of these sayings (sc. the tradition of the sayings of Jesus as a whole) arose not on Hellenistic but on Aramaic soil’,4 and this verdict applies especially to the parables. The parabolic tradition is thus seen to be integral to the teaching of Jesus and to have a high claim to authenticity. Although the fact that Jesus used parables in his teaching is thus beyond contest, it is strongly denied by many scholars that the original wording and meaning of his parables is identical with what is actually recorded in the Gospels. -

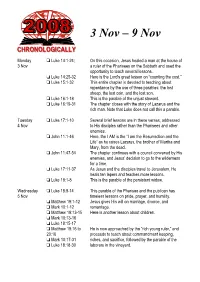

Monday 3 Nov Tuesday 4 Nov Wednesday 5 Nov Luke 14:1-24

Monday Luke 14:1-24; On this occasion, Jesus healed a man at the house of 3 Nov a ruler of the Pharisees on the Sabbath and used the opportunity to teach several lessons. Luke 14:25-32 Here is the Lord's great lesson on “counting the cost.” Luke 15:1-32 This entire chapter is devoted to teaching about repentance by the use of three parables: the lost sheep, the lost coin, and the lost son. Luke 16:1-18 This is the parable of the unjust steward. Luke 16:19-31 The chapter closes with the story of Lazarus and the rich man. Note that Luke does not call this a parable. Tuesday Luke 17:1-10 Several brief lessons are in these verses, addressed 4 Nov to His disciples rather than the Pharisees and other enemies. John 11:1-46 Here, the I AM is the “I am the Resurrection and the Life” as he raises Lazarus, the brother of Martha and Mary, from the dead. John 11:47-54 The chapter continues with a council convened by His enemies, and Jesus' decision to go to the wilderness for a time. Luke 17:11-37 As Jesus and the disciples travel to Jerusalem, He heals ten lepers and teaches more lessons. Luke 18:1-8 This is the parable of the persistent widow. Wednesday Luke 18:9-14 This parable of the Pharisee and the publican has 5 Nov timeless lessons on pride, prayer, and humility. Matthew 19:1-12 Jesus gives His will on marriage, divorce, and Mark 10:1-12 remarriage. -

Reading the Gospels for Lent

Reading the Gospels for Lent 2/26 John 1:1-14; Luke 1 Birth of John the Baptist 2/27 Matthew 1; Luke 2:1-38 Jesus’ birth 2/28 Matthew 2; Luke 2:39-52 Epiphany 2/29 Matthew 3:1-12; Mark 1:1-12; Luke 3:1-20; John 1:15-28 John the Baptist 3/2 Matthew 3:13-4:11; Mark 1:9-13; Luke 3:20-4:13; John 1:29-34 Baptism & Temptation 3/3 Matthew 4:12-25; Mark 1:14-45; Luke 4:14-5:16; John 1:35-51 Calling Disciples 3/4 John chapters 2-4 First miracles 3/5 Matthew 9:1-17; Mark 2:1-22; Luke 5:17-39; John 5 Dining with tax collectors 3/6 Matthew 12:1-21; Mark 2:23-3:19; Luke 6:1-19 Healing on the Sabbath 3/7 Matthew chapters 5-7; Luke 6:20-49 7 11:1-13 Sermon on the Mount 3/9 Matthew 8:1-13; & chapter 11; Luke chapter 7 Healing centurion’s servant 3/10 Matthew 13; Luke 8:1-12; Mark 4:1-34 Kingdom parables 3/11 Matthew 8:15-34 & 9:18-26; Mark 4:35-5:43; Luke 8:22-56 Calming sea; Legion; Jairus 3/12 Matthew 9:27-10:42; Mark 6:1-13; Luke 9:1-6 Sending out the Twelve 3/13 Matthew 14; Mark 6:14-56; Luke 9:7-17; John 6:1-24 Feeding 5000 3/14 John 6:25-71 3/16 Matthew 15 & Mark 7 Canaanite woman 3/17 Matthew 16; Mark 8; Luke 9:18-27 “Who do people say I am?” 3/18 Matthew 17; Mark 9:1-23; Luke 9:28-45 Transfiguration 3/19 Matthew 18; Mark 9:33-50 Luke 9:46-10:54 Who is the greatest? 3/20 John chapters 7 & 8 Jesus teaches in Jerusalem 3/21 John chapters 9 & 10 Good Shepherd 3/23 Luke chapters 12 & 13 3/24 Luke chapters 14 & 15 3/25 Luke 16:1-17:10 3/26 John 11 & Luke 17:11-18:14 3/27 Matthew 19:1-20:16; Mark 10:1-31; Luke 18:15-30 Divorce & other teachings 3/28 -

The Parables of Jesus

THE NEW TESTAMENT PARABLES OF JESUS Year 1– Quarter 4 by F. L. Booth ©2005 F. L. Booth Zion, IL 60099 CONTENTS PAGE PREFACE CHART NO. 1 - Parables of Jesus in Chronological Order CHART NO. 2 - Classification of the Parables of Jesus LESSON 1 - Parables of the Kingdom No. 1 The Parable of the Sower 1 - 1 LESSON 2 - Parables of the Kingdom No. 2 I. The Parable of the Tares 2 - 1 II. The Parable of the Seed Growing in Secret 2 - 3 III. The Parable of the Mustard Seed 2 - 5 IV. The Parable of the Leaven 2 - 7 LESSON 3 - Parables of the Kingdom No. 3 I. The Parable of the Hidden Treasure 3 - 1 II. The Parable of the Pearl of Great Price 3 - 3 III. The Parable of the Drawnet 3 - 5 IV. The Parable of the Laborers in the Vineyard 3 - 7 LESSON 4 - Parables of Forgiveness I. The Parable of the Two Debtors 4 - 1 II. The Parable of the Unmerciful Servant 4 - 5 LESSON 5 - A Parable of the Love of One's Neighbor The Parable of the Good Samaritan 5 - 1 A Parable of Jews and Gentiles The Parable of the Wicked Husbandmen 5 - 4 LESSON 6 - Parables of Praying I. The Parable of the Friend at Midnight 6 - 1 II. The Parable of the Importunate Widow 6 - 3 LESSON 7 - Parables of Self-Righteousness and Humility I. The Parable of the Chief Seats 7 - 1 II. The Parable of the Pharisee and the Publican 7 - 3 LESSON 8 - Parables of the Cost of Discipleship I. -

The Parable of the Weeds Among the Wheat (Matt 13:24-30, 36-43) And

JBL 114/4 (1995) 643-659 THE PARABLE OF THE WEEDS AMONG THE WHEAT (MATT 13:24-30,36-43) AND THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN THE KINGDOM AND THE CHURCH AS PORTRAYED IN THE GOSPEL OF MATTHEW ROBERT K. McIVER Avondale College, Cooranbong NSW 2265, Australia The parable of the weeds among the wheat provides an ideal vantage point from which to examine the distinctively Matthean concept of the kingdom of heaven. By any measure, this parable and its interpretation are distinctively Matthean, for besides being unique to the first Gospel, they contain several characteristically Matthean themes.' Moreover, the most appropriate interpre- tation of the parable has long been debated in the secondary literature. This debate often centers on the issue of the kingdom, and the parable may almost be considered a litmus test for the best approach to take for analyzing the Matthean concept of the kingdom of heaven. The parameters of this study are set by a desire to investigate the Mat- thean theology of the kingdom. As a consequence, though it is normally rele- gated to matters of secondary importance because of doubts as to whether it 1 Take, for example, the following phrases: (1) Keic Earat 6 Kcau)6ava6 Kai 6 Ppvuyio; rtiv 686vTxov (v. 42), cf. Matt 8:12; 13:50; 22:13; 24:51; 25:30; it is found elsewhere in the NT only in Luke 13:28. (2) ouvreXeta aii)vos (v. 39) and ?v i oTuv CtrexZ Toi aitSvo; (v. 40), cf. Matt 13:49; 24:3; 28:20; elsewhere in the NT the phrase is used only in Heb 9:26, there with the genitive plural. -

Matthew 21:1-11

Matthew 21:1-11 Finally, Jesus arrives at Jerusalem on what we know as “Palm Sunday.” It is significant that Jesus deliberately chose to enter Jerusalem riding on a donkey. Nowhere else in the Gospel do we read about Jesus traveling on an animal. Everywhere else He traveled, Jesus went on foot over land and on boat over sea (and one time on foot over the sea when He walked on the water!) – but we never find Him riding on a donkey – except when He enters Jerusalem. • Why this new mode of transportation? Zechariah 9:9-10 Rejoice greatly, O daughter of Zion! Shout aloud, O daughter of Jeruslaem! Lo, your king comes to you; triumphant and victorious is he, humble and riding on an ass, on a colt the foal of an ass…He shall command peace to the nations; his dominion shall be from sea to sea, and from the River to the ends of the earth. By riding into Jerusalem on a young donkey, Jesus, without saying a single word, was shouting out, “I am the Messiah-King coming to take my throne in Jerusalem!” If there were any questions about Who Jesus was, this action would have removed all doubt. Why? 1 Kings 1:1-4 Now King David was old and advanced in years… The big question was: Who will succeed David? He has many wives and multiple sons, therefore, who will be the next King? • Adonijah is the oldest living son (2:22) • Wouldn’t one assume he would be the next king? • Adonijah does assume this. -

April 5, 2020 Palm/Passion Sunday Fourth Sunday of Online Worship Dr

April 5, 2020 Palm/Passion Sunday Fourth Sunday of online worship Dr. Susan F. DeWyngaert Psalm 118:19-29 Zechariah 9:9-10 Matthew 21:1-11 Deliver Us! Save us, we beseech you, O Lord! O Lord, we beseech you, give us success! – Psalm 118: 25 The psalm we just read together, Psalm 118, was Martin Luther’s favorite. The great reformer spent 10 months hunkered down in a tiny apartment in Wartburg, Germany – sheltering in place, we might say, because the Emperor and the Pope disapproved of the things he was saying about the equality of all people under God, and they put a price on his head. I can imagine Luther singing the psalm alone in his room. He wrote: “This is the psalm I love … it has served me well and helped me out of grave troubles, when neither emperor, kings, wise men, clever men, nor saints, could help me.” i Ancient Israel agreed. Psalm 118 is a thanksgiving song, sung by God’s people for thousands of years. The Levites in the temple sang it as they prepared the Passover meal. Families sang it in their homes at the Seder. “The gates” the psalmist prays that God will open are the gates of Jerusalem. This is a song of faith and freedom, announcing faith that God will again open a way to freedom the same way God opened the sea to free the Israelite slaves long ago! It’s about the new Moses, God’s chosen deliverer. On Palm Sunday the people sang it: Blessed is the one who comes in the name of the Lord. -

The Parables of Jesus: Friendly Subversive Speech

The Parables of Jesus: Friendly Subversive Speech Introduction 4 Tell it Slant Typology and Parables The Four Gospels and Parables Messianic Consciousness Matthew’s Sermon of Parables 1 The Parable of the Sower 13 “Holy Seed” Isaiah’s Open Secret Jesus’ Interpretation Good-Soil Understanding 2 The Parable of the Weeds among the Wheat 22 Mustard Seeds and Yeast Echoes of Asaph Jesus’ Explanation 3 The Parables of the Hidden Treasure, the Pearl, and the Net 32 The Joy of the Gospel The Net New Treasures 4 The Parable of the Good Samaritan 37 Setting the Scene Augustine’s Allegory The Expert Who is my Neighbor? Messianic Edge 5 The Parable of the Friend at Midnight 50 Midnight Request Global Neighbors How Much More! 6 The Parable of the Rich Fool 55 Do We Practice What We Preach? The Meaning of Life All Kinds of Greed The Fool Jesus’ Hierarchy of Needs 7 The Parable of the Faithful Servants and the Exuberant Master 67 The Master is Coming! The Master Serves 8 The Parable of the Faithless Servant and the Furious Master 73 Managerial Responsibilities Managers of the Mysteries of God’s Revelation The Master’s Fury 1 9 The Parable of the Barren Fig Tree 80 Fig Tree Judgment Repentance Productivity 10 The Parable of the Great Banquet 86 The Narrow Door Jesus Will Not Be Managed Tension Around the Table Mundane Excuses The Host 11 The Parable of the Tower Builder and King at War 94 Christ-less Christianity Counting the Cost Who Among You? 12 The Parables of the Lost Sheep, the Lost Coin, and the Lost Sons 101 The Compassionate Father Prodigal -

BIBLE MEMORY VERSE ACTIVITIES “You Shall Love the Lord Your God with All Your Heart and with All Your Soul and with All Your Mind

Teacher’s Guide: Ages 8-9 Kings & Kingdoms Part 1: The Life of Jesus Unit 5, Lesson 25 The Vine and the Branches Lesson Aim: To understand what it means to remain in Jesus and bear fruit. THE WORSHIP Who God is: The King Who Teaches THE WORD Bible Story: John 15:1-8 What He has done: Jesus taught He is the Vine and we are the branches. Key Verse: John 15:4 THE WAY Christ Connection: Isaiah 27:3 BIBLE MEMORY VERSE “You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind… Love your neighbor as yourself.” Matthew 22:37, 39 Unit 5: The King Who Teaches—Parables 1 Bible Story What He Has Done Lesson Aim 23 The Lost Sheep, Jesus taught that God finds those To recognize we wander like Luke 15:4-7 who are lost. sheep and Jesus is our Shepherd. 24 The Sower, Jesus taught about four different To understand why some believe Luke 8:4-8, 11-15 responses to God’s Word. God’s Word and some do not. 25 The Vine and the Branches, Jesus taught He is the Vine and To understand what it means to John 15:1-8 we are the branches. remain in Jesus and bear fruit. 26 The Workers in the Vineyard, Jesus taught about a fair and To know God is fair and generous. Matthew 20:1-16 generous landowner. 27 The Great Banquet, Jesus taught about guests invited To see that we need to respond Luke 14:15-24 to a banquet. -

The Parables of Jesus: Better Than Fiction

Winter 2018 Book 1 The Parables of Jesus: Better Than Fiction Home Bible Studies Evangelical Free Church of Green Valley Coordinated with messages by Pastor Steve LoVellette Lessons prepared by Dave McCracken ii Introduction The parables of Jesus can be found in all the gospels, except for John, and in some of the non-canonical gospels, but are located mainly within the three Synoptic Gospels. They represent a main part of the teachings of Jesus, forming approximately one third of his recorded teachings. Bible scholar Madeline Boucher writes: The importance of the parables can hardly be overestimated. They comprise a substantial part of the recorded preaching of Jesus. The parables are generally regarded by scholars as among the sayings which we can confidently ascribe to the historical Jesus; they are, for the most part, authentic words of Jesus. Moreover, all of the great themes of Jesus' preaching are struck in the parables. Parables are not fables, not myths, not proverbs, not allegories. Jesus' parables are short stories that teach a moral or spiritual lesson by analogy or similarity. They are often stories based on the agricultural life that was intimately familiar to His original first century audience. It is the lesson of a parable that is important to us. The story is not important in itself; it may or may not be literally true. Jesus was the master of teaching in parables. His parables often have an unexpected twist or surprise ending that catches the reader's attention. They are also cleverly designed to draw listeners into new ways of thinking, new attitudes and new ways of acting. -

Luke's Parable of the Canny Steward

158 Luke’s Parable of the Canny Steward E Bruce Brooks University of Massachusetts at Amherst SEECR / University of North Carolina (31 Oct 2014) In the light of the Luke A/B/C formation model introduced in a previous study,1 I here consider what is usually called the Parable of the Unjust Steward (Lk 16:1-8), its context in Lk 15-16, and a possible, and less inscrutable, Chinese antecedent. Text. The Parable may be notably difficult,2 but its message is nonetheless obvious (be wise about the next world, just as worldlings are wise about this world, Lk 16:8b). There follow several comments on the parable: Lk 16:9, 10-12, and 13.3 The text goes: Lk 16:1. And he said also unto the disciples, There was a certain rich man who had a steward, and the same was accused unto him that he was wasting his goods. [2] And he called him and said unto him, What is this that I hear of thee? Render the account of thy stewardship; for thou canst be no longer steward. [3] And the steward said within himself, What shall I do, seeing that my lord taketh away the stewardship from me? I have not strength to dig; to beg I am ashamed. [4] I am resolved what to do, that, when I am put out of the stewardship, they may receive me into their houses. [5] And calling to him each one of his lord’s debtors, he said to the first, How much owest thou unto my lord? [6] And he said, A hundred measures of oil.