Concerning Electronegativity As a Basic Elemental Property and Why the Periodic Table Is Usually Represented in Its Medium Form

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Development of the Periodic Table and Its Consequences Citation: J

Firenze University Press www.fupress.com/substantia The Development of the Periodic Table and its Consequences Citation: J. Emsley (2019) The Devel- opment of the Periodic Table and its Consequences. Substantia 3(2) Suppl. 5: 15-27. doi: 10.13128/Substantia-297 John Emsley Copyright: © 2019 J. Emsley. This is Alameda Lodge, 23a Alameda Road, Ampthill, MK45 2LA, UK an open access, peer-reviewed article E-mail: [email protected] published by Firenze University Press (http://www.fupress.com/substantia) and distributed under the terms of the Abstract. Chemistry is fortunate among the sciences in having an icon that is instant- Creative Commons Attribution License, ly recognisable around the world: the periodic table. The United Nations has deemed which permits unrestricted use, distri- 2019 to be the International Year of the Periodic Table, in commemoration of the 150th bution, and reproduction in any medi- anniversary of the first paper in which it appeared. That had been written by a Russian um, provided the original author and chemist, Dmitri Mendeleev, and was published in May 1869. Since then, there have source are credited. been many versions of the table, but one format has come to be the most widely used Data Availability Statement: All rel- and is to be seen everywhere. The route to this preferred form of the table makes an evant data are within the paper and its interesting story. Supporting Information files. Keywords. Periodic table, Mendeleev, Newlands, Deming, Seaborg. Competing Interests: The Author(s) declare(s) no conflict of interest. INTRODUCTION There are hundreds of periodic tables but the one that is widely repro- duced has the approval of the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) and is shown in Fig.1. -

The Quantum Mechanical Model of the Atom

The Quantum Mechanical Model of the Atom Quantum Numbers In order to describe the probable location of electrons, they are assigned four numbers called quantum numbers. The quantum numbers of an electron are kind of like the electron’s “address”. No two electrons can be described by the exact same four quantum numbers. This is called The Pauli Exclusion Principle. • Principle quantum number: The principle quantum number describes which orbit the electron is in and therefore how much energy the electron has. - it is symbolized by the letter n. - positive whole numbers are assigned (not including 0): n=1, n=2, n=3 , etc - the higher the number, the further the orbit from the nucleus - the higher the number, the more energy the electron has (this is sort of like Bohr’s energy levels) - the orbits (energy levels) are also called shells • Angular momentum (azimuthal) quantum number: The azimuthal quantum number describes the sublevels (subshells) that occur in each of the levels (shells) described above. - it is symbolized by the letter l - positive whole number values including 0 are assigned: l = 0, l = 1, l = 2, etc. - each number represents the shape of a subshell: l = 0, represents an s subshell l = 1, represents a p subshell l = 2, represents a d subshell l = 3, represents an f subshell - the higher the number, the more complex the shape of the subshell. The picture below shows the shape of the s and p subshells: (notice the electron clouds) • Magnetic quantum number: All of the subshells described above (except s) have more than one orientation. -

The Past and Future of the Periodic Table

The Past and Future of the Periodic Table This stalwart symbol of the field of chemistry always faces scrutiny and debate Eric R. Scerri t graces the walls of lecture halls making up one period. The lengths elements, Döbereiner found that the Iand laboratories of all types, from of periods vary: The first has two ele- weight of the middle element—such as universities to industry. It is one of ments, the next two eight each, then 18 selenium in the triad formed by sulfur, the most powerful icons of science. It and 32, respectively, for the next pairs selenium and tellurium—had an atom- captures the essence of chemistry in of periods. Vertical columns make up ic weight that was the approximate one elegant pattern. The periodic table groups, of which there are 18, based average of the weights of the other two provides a concise way of understand- on similar chemical properties, related elements. Sulfur’s atomic weight, in ing how all known chemical elements to the number of electrons in the outer Döbereiner’s time, was 32.239, where- react with one another and enter into shell of the atoms, also called the va- as tellurium’s was 129.243, the average chemical bonding, and it helps to ex- lence shell. For instance, group 17, the of which is 80.741, or close to the then- plain the properties of each element halogens, all lack one electron to fill measured value for selenium, 79.264. that make it react in such a fashion. their valence shells, all tend to acquire The importance of this discovery lay But the periodic system is so funda- electrons during reactions, and all form in the marrying of qualitative chemical mental, pervasive and familiar in the acids with hydrogen. -

Essential Questions and Objectives

Essential Questions and Objectives • How does the configuration of electrons affect the atom’s properties? You’ll be able to: – Draw an orbital diagram for an element – Determine the electron configuration for an element – Explain the Pauli exclusion principle, Aufbau principle and Hund’s Rule Warm up Set your goals and curiosities for the unit on your tracker. Have your comparison table out for a stamp Bohr v QMM What are some features of the quantum mechanical model of the atom that are not included in the Bohr model? Quantum Mechanical Model • Electrons do not travel around the nucleus of an atom in orbits • They are found in energy levels at different distances away from the nucleus in orbitals • Orbital – region in space where there is a high probability of finding an electron. Atomic Orbitals Electrons cannot exist between energy levels (just like the rungs of a ladder). Principal quantum number (n) indicates the relative size and energy of atomic orbitals. n specifies the atom’s major energy levels also called the principal energy levels. Energy sublevels are contained within the principal energy levels. Ground-State Electron Configuration The arrangement of electrons in the atom is called the electron configuration. Shows where the electrons are - which principal energy levels, which sublevels - and how many electrons in each available space Orbital Filling • The order that electrons fill up orbitals does not follow the order of all n=1’s, then all n=2’s, then all n=3’s, etc. Electron configuration for... Oxygen How many electrons? There are rules to follow to know where they go .. -

Introduction to Chemistry

Introduction to Chemistry Author: Tracy Poulsen Digital Proofer Supported by CK-12 Foundation CK-12 Foundation is a non-profit organization with a mission to reduce the cost of textbook Introduction to Chem... materials for the K-12 market both in the U.S. and worldwide. Using an open-content, web-based Authored by Tracy Poulsen collaborative model termed the “FlexBook,” CK-12 intends to pioneer the generation and 8.5" x 11.0" (21.59 x 27.94 cm) distribution of high-quality educational content that will serve both as core text as well as provide Black & White on White paper an adaptive environment for learning. 250 pages ISBN-13: 9781478298601 Copyright © 2010, CK-12 Foundation, www.ck12.org ISBN-10: 147829860X Except as otherwise noted, all CK-12 Content (including CK-12 Curriculum Material) is made Please carefully review your Digital Proof download for formatting, available to Users in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution/Non-Commercial/Share grammar, and design issues that may need to be corrected. Alike 3.0 Unported (CC-by-NC-SA) License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc- sa/3.0/), as amended and updated by Creative Commons from time to time (the “CC License”), We recommend that you review your book three times, with each time focusing on a different aspect. which is incorporated herein by this reference. Specific details can be found at http://about.ck12.org/terms. Check the format, including headers, footers, page 1 numbers, spacing, table of contents, and index. 2 Review any images or graphics and captions if applicable. -

Science-8 Module-8 Version-3.Pdf

Republic of the Philippines Department of Education Regional Office IX, Zamboanga Peninsula 8 SCIENCE Quarter 3 - Module 8 PERIODIC PROPERTIES OF ELEMENTS Name of Learner: ___________________________ Grade & Section: ___________________________ Name of School: ___________________________ Science- Grade 8 Support Material for Independent Learning Engagement (SMILE) Quarter 3 - Module 8: Periodic Properties of Elements First Edition, 2021 Republic Act 8293, section 176 states that: No copyright shall subsist in any work of the Government of the Philippines. However, prior approval of the government agency or office wherein the work is created shall be necessary for the exploitation of such work for a profit. Such agency or office may, among other things, impose as a condition the payment of royalty. Borrowed materials (i.e., songs, stories, poems, pictures, photos, brand names, trademarks, etc.) included in this book are owned by their respective copyright holders. Every effort has been exerted to locate and seek permission to use these materials from their respective copyright owners. The publisher and authors do not represent nor claim ownership over them. Development Team of the Module Writer: Galo M. Salinas Editor: Teodelen S. Aleta Reviewers: Teodelen S. Aleta, Zyhrine P. Mayormita Lay-out Artists: Zyhrine P. Mayormita, Chris Raymund M. Bermudo Management Team: Virgilio P. Batan Jr. - Schools Division Superintendent Lourma I. Poculan - Asst. Schools Division Superintendent Amelinda D. Montero - Chief Education Supervisor, CID Nur N. Hussien - Chief Education Supervisor, SGOD Ronillo S. Yarag - Education Program Supervisor, LRMS Zyhrine P. Mayormita - Education Program Supervisor, Science Leo Martinno O. Alejo - Project Development Officer II, LRMS Janette A. Zamoras - Public Schools District Supervisor Adrian G. -

Density Functional Theory

Density Functional Theory Fundamentals Video V.i Density Functional Theory: New Developments Donald G. Truhlar Department of Chemistry, University of Minnesota Support: AFOSR, NSF, EMSL Why is electronic structure theory important? Most of the information we want to know about chemistry is in the electron density and electronic energy. dipole moment, Born-Oppenheimer charge distribution, approximation 1927 ... potential energy surface molecular geometry barrier heights bond energies spectra How do we calculate the electronic structure? Example: electronic structure of benzene (42 electrons) Erwin Schrödinger 1925 — wave function theory All the information is contained in the wave function, an antisymmetric function of 126 coordinates and 42 electronic spin components. Theoretical Musings! ● Ψ is complicated. ● Difficult to interpret. ● Can we simplify things? 1/2 ● Ψ has strange units: (prob. density) , ● Can we not use a physical observable? ● What particular physical observable is useful? ● Physical observable that allows us to construct the Hamiltonian a priori. How do we calculate the electronic structure? Example: electronic structure of benzene (42 electrons) Erwin Schrödinger 1925 — wave function theory All the information is contained in the wave function, an antisymmetric function of 126 coordinates and 42 electronic spin components. Pierre Hohenberg and Walter Kohn 1964 — density functional theory All the information is contained in the density, a simple function of 3 coordinates. Electronic structure (continued) Erwin Schrödinger -

Electron Density Functions for Simple Molecules (Chemical Bonding/Excited States) RALPH G

Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 77, No. 4, pp. 1725-1727, April 1980 Chemistry Electron density functions for simple molecules (chemical bonding/excited states) RALPH G. PEARSON AND WILLIAM E. PALKE Department of Chemistry, University of California, Santa Barbara, California 93106 Contributed by Ralph G. Pearson, January 8, 1980 ABSTRACT Trial electron density functions have some If each component of the charge density is centered on a conceptual and computational advantages over wave functions. single point, the calculation of the potential energy is made The properties of some simple density functions for H+2 and H2 are examined. It appears that for a diatomic molecule a good much easier. However, the kinetic energy is often difficult to density function would be given by p = N(A2 + B2), in which calculate for densities containing several one-center terms. For A and B are short sums of s, p, d, etc. orbitals centered on each a wave function that is composed of one orbital, the kinetic nucleus. Some examples are also given for electron densities that energy can be written in terms of the electron density as are appropriate for excited states. T = 1/8 (VP)2dr [5] Primarily because of the work of Hohenberg, Kohn, and Sham p (1, 2), there has been great interest in studying quantum me- and in most cases this integral was evaluated numerically in chanical problems by using the electron density function rather cylindrical coordinates. The X integral was trivial in every case, than the wave function as a means of approach. Examples of and the z and r integrations were carried out via two-dimen- the use of the electron density include studies of chemical sional Gaussian bonding in molecules (3, 4), solid state properties (5), inter- quadrature. -

Chemistry 1000 Lecture 8: Multielectron Atoms

Chemistry 1000 Lecture 8: Multielectron atoms Marc R. Roussel September 14, 2018 Marc R. Roussel Multielectron atoms September 14, 2018 1 / 23 Spin Spin Spin (with associated quantum number s) is a type of angular momentum attached to a particle. Every particle of the same kind (e.g. every electron) has the same value of s. Two types of particles: Fermions: s is a half integer 1 Examples: electrons, protons, neutrons (s = 2 ) Bosons: s is an integer Example: photons (s = 1) Marc R. Roussel Multielectron atoms September 14, 2018 2 / 23 Spin Spin magnetic quantum number All types of angular momentum obey similar rules. There is a spin magnetic quantum number ms which gives the z component of the spin angular momentum vector: Sz = ms ~ The value of ms can be −s; −s + 1;:::; s. 1 1 1 For electrons, s = 2 so ms can only take the values − 2 or 2 . Marc R. Roussel Multielectron atoms September 14, 2018 3 / 23 Spin Stern-Gerlach experiment How do we know that electrons (e.g.) have spin? Source: Theresa Knott, Wikimedia Commons, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Stern-Gerlach_experiment.PNG Marc R. Roussel Multielectron atoms September 14, 2018 4 / 23 Spin Pauli exclusion principle No two fermions can share a set of quantum numbers. Marc R. Roussel Multielectron atoms September 14, 2018 5 / 23 Multielectron atoms Multielectron atoms Electrons occupy orbitals similar (in shape and angular momentum) to those of hydrogen. Same orbital names used, e.g. 1s, 2px , etc. The number of orbitals of each type is still set by the number of possible values of m`, so e.g. -

Study of Heavy Metal Contamination on Soil and Water in Major Vegetable Tracks of Pathanamthitta District, Kerala, India

International Journal of Engineering Science Invention ISSN (Online): 2319 – 6734, ISSN (Print): 2319 – 6726 www.ijesi.org ||Volume 3 Issue 12 || December 2014 || PP.34-39 Study of Heavy Metal Contamination on Soil and Water in Major Vegetable Tracks of Pathanamthitta District, Kerala, India 1,Shakhila.S.S, 2,Keshav Mohan 1.PhD (Environmental Chemistry) Scholor, Karpagam University, Coimbatore 2.Director, Institute of Land and Disaster Management, Govt of Kerala ABSTRACT : Heavy metal contamination on soil and water causes a serious environmental problem because it does not biodegrade. It accumulates in different levels of the food chain. The aim of the present study is to assess the heavy metal contamination on soil and water in the major vegetable tracks of Pathanamthitta district, Kerala, India. The concentrations of heavy metals namely Zinc, Iron, Lead,Chromium, Copper and Cadmium were determined by Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy. The concentration of heavy metals in soil from the study sites ranged from Zn (0.07-0.2mg/kg), Fe(0.2-1.4 mg/kg), Pb(0-0.5mg/kg), and Cu (0.1-1.0 mg/kg) respectively. Iron was detected in water samples (0.35-0.41 mg/kg). Water sample showed low values of BOD , COD and slightly acidic pH. KEY WORDS: AAS, Heavy metals, Pesticide, pH, Pesticides impact assessment. I. INTRODUCTION The term heavy metal refers to any metallic chemical element that is toxic. Examples of heavy metals include Iron, Mercury, Cadmium, Arsenic, Copper, Chromium, Thallium, Lead etc. Of these Iron, Cobalt, Copper, Manganese, Molybdenum, and Zinc are essential elements. Other heavy metals such as Mercury, Plutonium, and Lead are toxic and their accumulation over time in the bodies of animals can cause serious health problems. -

POST MENDELEEVIAN EVOLUTION of the PERIODIC TABLE (.Pdf)

Post Mendeleevian Evolution of the Periodic Table Gary Katz Periodic Round Table We are here in the centenary of the death of Mendeleev, whose life defines the epoch of the Periodic Table. To his memory we respectfully dedicate this, our plan to revitalize his invention, the Periodic Table. Since Mendeleev’s death in 1907, the only substantive changes in the Table have been the insertion of new elements; most fall into the eighth period with another seven in the main body of the Table, but only three of these are stable non-radioactive species. The quantum chemical results of Niels Bohr came along early in the century elucidating the electronic con- figurations of the atoms, explaining a great deal about what made the Periodic Table periodic. By mid century when Seaborg proposed an actinide series to parallel the lanthanide series, including a number of the new transuranium elements, the official Table we now have was es- sentially in place. It has not changed fundamentally since that time. In my previous paper “An Eight-period Table for the 21st Century” (1) I discussed the evolution of the 8-period concept and some of the people who have worked toward the goal of transforming the Periodic Table in this fashion. Since 2001, I have changed my terminology to agree with that of other writers: the 8-period table is now to be called the left-step table. This is a phrase coined by physical chemist Henry Bent, who proposed it back in the 80’s, and it allows for the expansion of the table into periods beyond the eighth—a critical area of future development for the Periodic Table. -

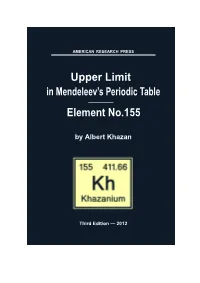

Upper Limit in Mendeleev's Periodic Table Element No.155

AMERICAN RESEARCH PRESS Upper Limit in Mendeleev’s Periodic Table Element No.155 by Albert Khazan Third Edition — 2012 American Research Press Albert Khazan Upper Limit in Mendeleev’s Periodic Table — Element No. 155 Third Edition with some recent amendments contained in new chapters Edited and prefaced by Dmitri Rabounski Editor-in-Chief of Progress in Physics and The Abraham Zelmanov Journal Rehoboth, New Mexico, USA — 2012 — This book can be ordered in a paper bound reprint from: Books on Demand, ProQuest Information and Learning (University of Microfilm International) 300 N. Zeeb Road, P. O. Box 1346, Ann Arbor, MI 48106-1346, USA Tel.: 1-800-521-0600 (Customer Service) http://wwwlib.umi.com/bod/ This book can be ordered on-line from: Publishing Online, Co. (Seattle, Washington State) http://PublishingOnline.com Copyright c Albert Khazan, 2009, 2010, 2012 All rights reserved. Electronic copying, print copying and distribution of this book for non-commercial, academic or individual use can be made by any user without permission or charge. Any part of this book being cited or used howsoever in other publications must acknowledge this publication. No part of this book may be re- produced in any form whatsoever (including storage in any media) for commercial use without the prior permission of the copyright holder. Requests for permission to reproduce any part of this book for commercial use must be addressed to the Author. The Author retains his rights to use this book as a whole or any part of it in any other publications and in any way he sees fit.