The Quantum Mechanical Model of the Atom

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unit 1 Old Quantum Theory

UNIT 1 OLD QUANTUM THEORY Structure Introduction Objectives li;,:overy of Sub-atomic Particles Earlier Atom Models Light as clectromagnetic Wave Failures of Classical Physics Black Body Radiation '1 Heat Capacity Variation Photoelectric Effect Atomic Spectra Planck's Quantum Theory, Black Body ~diation. and Heat Capacity Variation Einstein's Theory of Photoelectric Effect Bohr Atom Model Calculation of Radius of Orbits Energy of an Electron in an Orbit Atomic Spectra and Bohr's Theory Critical Analysis of Bohr's Theory Refinements in the Atomic Spectra The61-y Summary Terminal Questions Answers 1.1 INTRODUCTION The ideas of classical mechanics developed by Galileo, Kepler and Newton, when applied to atomic and molecular systems were found to be inadequate. Need was felt for a theory to describe, correlate and predict the behaviour of the sub-atomic particles. The quantum theory, proposed by Max Planck and applied by Einstein and Bohr to explain different aspects of behaviour of matter, is an important milestone in the formulation of the modern concept of atom. In this unit, we will study how black body radiation, heat capacity variation, photoelectric effect and atomic spectra of hydrogen can be explained on the basis of theories proposed by Max Planck, Einstein and Bohr. They based their theories on the postulate that all interactions between matter and radiation occur in terms of definite packets of energy, known as quanta. Their ideas, when extended further, led to the evolution of wave mechanics, which shows the dual nature of matter -

Quantum Theory of the Hydrogen Atom

Quantum Theory of the Hydrogen Atom Chemistry 35 Fall 2000 Balmer and the Hydrogen Spectrum n 1885: Johann Balmer, a Swiss schoolteacher, empirically deduced a formula which predicted the wavelengths of emission for Hydrogen: l (in Å) = 3645.6 x n2 for n = 3, 4, 5, 6 n2 -4 •Predicts the wavelengths of the 4 visible emission lines from Hydrogen (which are called the Balmer Series) •Implies that there is some underlying order in the atom that results in this deceptively simple equation. 2 1 The Bohr Atom n 1913: Niels Bohr uses quantum theory to explain the origin of the line spectrum of hydrogen 1. The electron in a hydrogen atom can exist only in discrete orbits 2. The orbits are circular paths about the nucleus at varying radii 3. Each orbit corresponds to a particular energy 4. Orbit energies increase with increasing radii 5. The lowest energy orbit is called the ground state 6. After absorbing energy, the e- jumps to a higher energy orbit (an excited state) 7. When the e- drops down to a lower energy orbit, the energy lost can be given off as a quantum of light 8. The energy of the photon emitted is equal to the difference in energies of the two orbits involved 3 Mohr Bohr n Mathematically, Bohr equated the two forces acting on the orbiting electron: coulombic attraction = centrifugal accelleration 2 2 2 -(Z/4peo)(e /r ) = m(v /r) n Rearranging and making the wild assumption: mvr = n(h/2p) n e- angular momentum can only have certain quantified values in whole multiples of h/2p 4 2 Hydrogen Energy Levels n Based on this model, Bohr arrived at a simple equation to calculate the electron energy levels in hydrogen: 2 En = -RH(1/n ) for n = 1, 2, 3, 4, . -

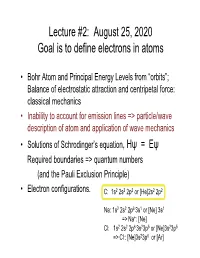

Lecture #2: August 25, 2020 Goal Is to Define Electrons in Atoms

Lecture #2: August 25, 2020 Goal is to define electrons in atoms • Bohr Atom and Principal Energy Levels from “orbits”; Balance of electrostatic attraction and centripetal force: classical mechanics • Inability to account for emission lines => particle/wave description of atom and application of wave mechanics • Solutions of Schrodinger’s equation, Hψ = Eψ Required boundaries => quantum numbers (and the Pauli Exclusion Principle) • Electron configurations. C: 1s2 2s2 2p2 or [He]2s2 2p2 Na: 1s2 2s2 2p6 3s1 or [Ne] 3s1 => Na+: [Ne] Cl: 1s2 2s2 2p6 3s23p5 or [Ne]3s23p5 => Cl-: [Ne]3s23p6 or [Ar] What you already know: Quantum Numbers: n, l, ml , ms n is the principal quantum number, indicates the size of the orbital, has all positive integer values of 1 to ∞(infinity) (Bohr’s discrete orbits) l (angular momentum) orbital 0s l is the angular momentum quantum number, 1p represents the shape of the orbital, has integer values of (n – 1) to 0 2d 3f ml is the magnetic quantum number, represents the spatial direction of the orbital, can have integer values of -l to 0 to l Other terms: electron configuration, noble gas configuration, valence shell ms is the spin quantum number, has little physical meaning, can have values of either +1/2 or -1/2 Pauli Exclusion principle: no two electrons can have all four of the same quantum numbers in the same atom (Every electron has a unique set.) Hund’s Rule: when electrons are placed in a set of degenerate orbitals, the ground state has as many electrons as possible in different orbitals, and with parallel spin. -

Principal, Azimuthal and Magnetic Quantum Numbers and the Magnitude of Their Values

268 A Textbook of Physical Chemistry – Volume I Principal, Azimuthal and Magnetic Quantum Numbers and the Magnitude of Their Values The Schrodinger wave equation for hydrogen and hydrogen-like species in the polar coordinates can be written as: 1 휕 휕휓 1 휕 휕휓 1 휕2휓 8휋2휇 푍푒2 (406) [ (푟2 ) + (푆푖푛휃 ) + ] + (퐸 + ) 휓 = 0 푟2 휕푟 휕푟 푆푖푛휃 휕휃 휕휃 푆푖푛2휃 휕휙2 ℎ2 푟 After separating the variables present in the equation given above, the solution of the differential equation was found to be 휓푛,푙,푚(푟, 휃, 휙) = 푅푛,푙. 훩푙,푚. 훷푚 (407) 2푍푟 푘 (408) 3 푙 푘=푛−푙−1 (−1)푘+1[(푛 + 푙)!]2 ( ) 2푍 (푛 − 푙 − 1)! 푍푟 2푍푟 푛푎 √ 0 = ( ) [ 3] . exp (− ) . ( ) . ∑ 푛푎0 2푛{(푛 + 푙)!} 푛푎0 푛푎0 (푛 − 푙 − 1 − 푘)! (2푙 + 1 + 푘)! 푘! 푘=0 (2푙 + 1)(푙 − 푚)! 1 × √ . 푃푚(퐶표푠 휃) × √ 푒푖푚휙 2(푙 + 푚)! 푙 2휋 It is obvious that the solution of equation (406) contains three discrete (n, l, m) and three continuous (r, θ, ϕ) variables. In order to be a well-behaved function, there are some conditions over the values of discrete variables that must be followed i.e. boundary conditions. Therefore, we can conclude that principal (n), azimuthal (l) and magnetic (m) quantum numbers are obtained as a solution of the Schrodinger wave equation for hydrogen atom; and these quantum numbers are used to define various quantum mechanical states. In this section, we will discuss the properties and significance of all these three quantum numbers one by one. Principal Quantum Number The principal quantum number is denoted by the symbol n; and can have value 1, 2, 3, 4, 5…..∞. -

Vibrational Quantum Number

Fundamentals in Biophotonics Quantum nature of atoms, molecules – matter Aleksandra Radenovic [email protected] EPFL – Ecole Polytechnique Federale de Lausanne Bioengineering Institute IBI 26. 03. 2018. Quantum numbers •The four quantum numbers-are discrete sets of integers or half- integers. –n: Principal quantum number-The first describes the electron shell, or energy level, of an atom –ℓ : Orbital angular momentum quantum number-as the angular quantum number or orbital quantum number) describes the subshell, and gives the magnitude of the orbital angular momentum through the relation Ll2 ( 1) –mℓ:Magnetic (azimuthal) quantum number (refers, to the direction of the angular momentum vector. The magnetic quantum number m does not affect the electron's energy, but it does affect the probability cloud)- magnetic quantum number determines the energy shift of an atomic orbital due to an external magnetic field-Zeeman effect -s spin- intrinsic angular momentum Spin "up" and "down" allows two electrons for each set of spatial quantum numbers. The restrictions for the quantum numbers: – n = 1, 2, 3, 4, . – ℓ = 0, 1, 2, 3, . , n − 1 – mℓ = − ℓ, − ℓ + 1, . , 0, 1, . , ℓ − 1, ℓ – –Equivalently: n > 0 The energy levels are: ℓ < n |m | ≤ ℓ ℓ E E 0 n n2 Stern-Gerlach experiment If the particles were classical spinning objects, one would expect the distribution of their spin angular momentum vectors to be random and continuous. Each particle would be deflected by a different amount, producing some density distribution on the detector screen. Instead, the particles passing through the Stern–Gerlach apparatus are deflected either up or down by a specific amount. -

Lecture 3: Particle in a 1D Box

Lecture 3: Particle in a 1D Box First we will consider a free particle moving in 1D so V (x) = 0. The TDSE now reads ~2 d2ψ(x) = Eψ(x) −2m dx2 which is solved by the function ψ = Aeikx where √2mE k = ± ~ A general solution of this equation is ψ(x) = Aeikx + Be−ikx where A and B are arbitrary constants. It can also be written in terms of sines and cosines as ψ(x) = C sin(kx) + D cos(kx) The constants appearing in the solution are determined by the boundary conditions. For a free particle that can be anywhere, there is no boundary conditions, so k and thus E = ~2k2/2m can take any values. The solution of the form eikx corresponds to a wave travelling in the +x direction and similarly e−ikx corresponds to a wave travelling in the -x direction. These are eigenfunctions of the momentum operator. Since the particle is free, it is equally likely to be anywhere so ψ∗(x)ψ(x) is independent of x. Incidently, it cannot be normalized because the particle can be found anywhere with equal probability. 1 Now, let us confine the particle to a region between x = 0 and x = L. To do this, we choose our interaction potential V (x) as follows V (x) = 0 for 0 x L ≤ ≤ = otherwise ∞ It is always a good idea to plot the potential energy, when it is a function of a single variable, as shown in Fig.1. The TISE is now given by V(x) V=infinity V=0 V=infinity x 0 L ~2 d2ψ(x) + V (x)ψ(x) = Eψ(x) −2m dx2 First consider the region outside the box where V (x) = . -

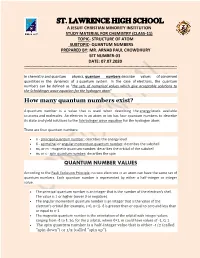

Magnetic Quantum Number: Describes the Orbital of the Subshell Ms Or S - Spin Quantum Number: Describes the Spin QUANTUM NUMBER VALUES

ST. LAWRENCE HIGH SCHOOL A JESUIT CHRISTIAN MINORITY INSTITUTION STUDY MATERIAL FOR CHEMISTRY (CLASS-11) TOPIC- STRUCTURE OF ATOM SUBTOPIC- QUANTUM NUMBERS PREPARED BY: MR. ARNAB PAUL CHOWDHURY SET NUMBER-03 DATE: 07.07.2020 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- In chemistry and quantum physics, quantum numbers describe values of conserved quantities in the dynamics of a quantum system. In the case of electrons, the quantum numbers can be defined as "the sets of numerical values which give acceptable solutions to the Schrödinger wave equation for the hydrogen atom". How many quantum numbers exist? A quantum number is a value that is used when describing the energy levels available to atoms and molecules. An electron in an atom or ion has four quantum numbers to describe its state and yield solutions to the Schrödinger wave equation for the hydrogen atom. There are four quantum numbers: n - principal quantum number: describes the energy level ℓ - azimuthal or angular momentum quantum number: describes the subshell mℓ or m - magnetic quantum number: describes the orbital of the subshell ms or s - spin quantum number: describes the spin QUANTUM NUMBER VALUES According to the Pauli Exclusion Principle, no two electrons in an atom can have the same set of quantum numbers. Each quantum number is represented by either a half-integer or integer value. The principal quantum number is an integer that is the number of the electron's shell. The value is 1 or higher (never 0 or negative). The angular momentum quantum number is an integer that is the value of the electron's orbital (for example, s=0, p=1). -

4 Nuclear Magnetic Resonance

Chapter 4, page 1 4 Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Pieter Zeeman observed in 1896 the splitting of optical spectral lines in the field of an electromagnet. Since then, the splitting of energy levels proportional to an external magnetic field has been called the "Zeeman effect". The "Zeeman resonance effect" causes magnetic resonances which are classified under radio frequency spectroscopy (rf spectroscopy). In these resonances, the transitions between two branches of a single energy level split in an external magnetic field are measured in the megahertz and gigahertz range. In 1944, Jevgeni Konstantinovitch Savoiski discovered electron paramagnetic resonance. Shortly thereafter in 1945, nuclear magnetic resonance was demonstrated almost simultaneously in Boston by Edward Mills Purcell and in Stanford by Felix Bloch. Nuclear magnetic resonance was sometimes called nuclear induction or paramagnetic nuclear resonance. It is generally abbreviated to NMR. So as not to scare prospective patients in medicine, reference to the "nuclear" character of NMR is dropped and the magnetic resonance based imaging systems (scanner) found in hospitals are simply referred to as "magnetic resonance imaging" (MRI). 4.1 The Nuclear Resonance Effect Many atomic nuclei have spin, characterized by the nuclear spin quantum number I. The absolute value of the spin angular momentum is L =+h II(1). (4.01) The component in the direction of an applied field is Lz = Iz h ≡ m h. (4.02) The external field is usually defined along the z-direction. The magnetic quantum number is symbolized by Iz or m and can have 2I +1 values: Iz ≡ m = −I, −I+1, ..., I−1, I. -

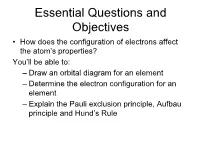

Essential Questions and Objectives

Essential Questions and Objectives • How does the configuration of electrons affect the atom’s properties? You’ll be able to: – Draw an orbital diagram for an element – Determine the electron configuration for an element – Explain the Pauli exclusion principle, Aufbau principle and Hund’s Rule Warm up Set your goals and curiosities for the unit on your tracker. Have your comparison table out for a stamp Bohr v QMM What are some features of the quantum mechanical model of the atom that are not included in the Bohr model? Quantum Mechanical Model • Electrons do not travel around the nucleus of an atom in orbits • They are found in energy levels at different distances away from the nucleus in orbitals • Orbital – region in space where there is a high probability of finding an electron. Atomic Orbitals Electrons cannot exist between energy levels (just like the rungs of a ladder). Principal quantum number (n) indicates the relative size and energy of atomic orbitals. n specifies the atom’s major energy levels also called the principal energy levels. Energy sublevels are contained within the principal energy levels. Ground-State Electron Configuration The arrangement of electrons in the atom is called the electron configuration. Shows where the electrons are - which principal energy levels, which sublevels - and how many electrons in each available space Orbital Filling • The order that electrons fill up orbitals does not follow the order of all n=1’s, then all n=2’s, then all n=3’s, etc. Electron configuration for... Oxygen How many electrons? There are rules to follow to know where they go .. -

A Relativistic Electron in a Coulomb Potential

A Relativistic Electron in a Coulomb Potential Alfred Whitehead Physics 518, Fall 2009 The Problem Solve the Dirac Equation for an electron in a Coulomb potential. Identify the conserved quantum numbers. Specify the degeneracies. Compare with solutions of the Schrödinger equation including relativistic and spin corrections. Approach My approach follows that taken by Dirac in [1] closely. A few modifications taken from [2] and [3] are included, particularly in regards to the final quantum numbers chosen. The general strategy is to first find a set of transformations which turn the Hamiltonian for the system into a form that depends only on the radial variables r and pr. Once this form is found, I solve it to find the energy eigenvalues and then discuss the energy spectrum. The Radial Dirac Equation We begin with the electromagnetic Hamiltonian q H = p − cρ ~σ · ~p − A~ + ρ mc2 (1) 0 1 c 3 with 2 0 0 1 0 3 6 0 0 0 1 7 ρ1 = 6 7 (2) 4 1 0 0 0 5 0 1 0 0 2 1 0 0 0 3 6 0 1 0 0 7 ρ3 = 6 7 (3) 4 0 0 −1 0 5 0 0 0 −1 1 2 0 1 0 0 3 2 0 −i 0 0 3 2 1 0 0 0 3 6 1 0 0 0 7 6 i 0 0 0 7 6 0 −1 0 0 7 ~σ = 6 7 ; 6 7 ; 6 7 (4) 4 0 0 0 1 5 4 0 0 0 −i 5 4 0 0 1 0 5 0 0 1 0 0 0 i 0 0 0 0 −1 We note that, for the Coulomb potential, we can set (using cgs units): Ze2 p = −eΦ = − o r A~ = 0 This leads us to this form for the Hamiltonian: −Ze2 H = − − cρ ~σ · ~p + ρ mc2 (5) r 1 3 We need to get equation 5 into a form which depends not on ~p, but only on the radial variables r and pr. -

Quantum Spin Systems and Their Local and Long-Time Properties Carolee Wheeler Faculty Advisor: Robert Sims

URA Project Proposal Quantum Spin Systems and Their Local and Long-Time Properties Carolee Wheeler Faculty Advisor: Robert Sims In quantum mechanics, spin is an important concept having to do with atomic nuclei, hadrons, and elementary particles. Spin may be thought of as a measure of a particle’s rotation about its axis. However, spin differs from orbital angular momentum in the sense that the particles may carry integer or half-integer quantum numbers, i.e. 0, 1/2, 1, 3/2, 2, etc., whereas orbital angular momentum may only take integer quantum numbers. Furthermore, the spin of a charged elementary particle is related to a magnetic dipole moment. All quantum mechanic particles have an inherent spin. This is due to the fact that elementary particles (such as photons, electrons, or quarks) cannot be divided into smaller entities. In other words, they cannot be viewed as particles that are made up of individual, smaller particles that rotate around a common center. Thus, the spin that elementary particles carry is an intrinsic property [1]. An important characteristic of spin in quantum mechanics is that it is quantized. The magnitude of spin takes values S = h s(s + )1 , with h being the reduced Planck’s constant and s being the spin quantum number (a non- negative integer or half-integer). Spin may also be viewed in composite particles, and is calculated by summing the spins of the constituent particles. In the case of atoms and molecules, spin is the sum of the spins of unpaired electrons [1]. Particles with spin can possess a magnetic moment. -

The Principal Quantum Number the Azimuthal Quantum Number The

To completely describe an electron in an atom, four quantum numbers are needed: energy (n), angular momentum (ℓ), magnetic moment (mℓ), and spin (ms). The Principal Quantum Number This quantum number describes the electron shell or energy level of an atom. The value of n ranges from 1 to the shell containing the outermost electron of that atom. For example, in caesium (Cs), the outermost valence electron is in the shell with energy level 6, so an electron incaesium can have an n value from 1 to 6. For particles in a time-independent potential, as per the Schrödinger equation, it also labels the nth eigen value of Hamiltonian (H). This number has a dependence only on the distance between the electron and the nucleus (i.e. the radial coordinate r). The average distance increases with n, thus quantum states with different principal quantum numbers are said to belong to different shells. The Azimuthal Quantum Number The angular or orbital quantum number, describes the sub-shell and gives the magnitude of the orbital angular momentum through the relation. ℓ = 0 is called an s orbital, ℓ = 1 a p orbital, ℓ = 2 a d orbital, and ℓ = 3 an f orbital. The value of ℓ ranges from 0 to n − 1 because the first p orbital (ℓ = 1) appears in the second electron shell (n = 2), the first d orbital (ℓ = 2) appears in the third shell (n = 3), and so on. This quantum number specifies the shape of an atomic orbital and strongly influences chemical bonds and bond angles.