ACCESS to WATER Rights, Obligations and the Bangalore Situation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dictionary of Martyrs: India's Freedom Struggle

DICTIONARY OF MARTYRS INDIA’S FREEDOM STRUGGLE (1857-1947) Vol. 5 Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu & Kerala ii Dictionary of Martyrs: India’s Freedom Struggle (1857-1947) Vol. 5 DICTIONARY OF MARTYRSMARTYRS INDIA’S FREEDOM STRUGGLE (1857-1947) Vol. 5 Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu & Kerala General Editor Arvind P. Jamkhedkar Chairman, ICHR Executive Editor Rajaneesh Kumar Shukla Member Secretary, ICHR Research Consultant Amit Kumar Gupta Research and Editorial Team Ashfaque Ali Md. Naushad Ali Md. Shakeeb Athar Muhammad Niyas A. Published by MINISTRY OF CULTURE, GOVERNMENT OF IDNIA AND INDIAN COUNCIL OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH iv Dictionary of Martyrs: India’s Freedom Struggle (1857-1947) Vol. 5 MINISTRY OF CULTURE, GOVERNMENT OF INDIA and INDIAN COUNCIL OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH First Edition 2018 Published by MINISTRY OF CULTURE Government of India and INDIAN COUNCIL OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH 35, Ferozeshah Road, New Delhi - 110 001 © ICHR & Ministry of Culture, GoI No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. ISBN 978-81-938176-1-2 Printed in India by MANAK PUBLICATIONS PVT. LTD B-7, Saraswati Complex, Subhash Chowk, Laxmi Nagar, New Delhi 110092 INDIA Phone: 22453894, 22042529 [email protected] State Co-ordinators and their Researchers Andhra Pradesh & Telangana Karnataka (Co-ordinator) (Co-ordinator) V. Ramakrishna B. Surendra Rao S.K. Aruni Research Assistants Research Assistants V. Ramakrishna Reddy A.B. Vaggar I. Sudarshan Rao Ravindranath B.Venkataiah Tamil Nadu Kerala (Co-ordinator) (Co-ordinator) N. -

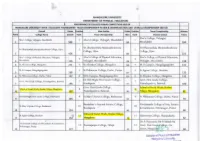

College Performance

MANGALORE UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF PHYSICAL EDUCATION PERFORMANCE OF COLLEGES IN MUIC COMPETITIONS 2019-20 MANGALORE UNIVERSITY INTER- COLLEGIATE TOURNAMENT- TEAM CHAMPIONSHIP IN MEN & WOMEN SECTION AND OVERALL CHAMPIONSHIP 2019-20 Overall Points Positior Men Section Points Position Team Championship Women Rank College Name Overall Rank Team Championship Men Rank Women Section Points Alva's College, Vidyagiri, Alva's College, Vidyagiri, Moodabidri 1 Alva 's College, Vidyagiri, Moodabidri 1 1 583 299 Moodabidri 284 Sri Dharmasthala Manjunatheshwara Sri Dharmasthala Manjunatheshwara Sri Dharmasthala Manjunatheshwara College, Ujir~ 2 2 College, Ujire College, Ujire 2 424 202 222 Ah· a·' College of Physical Education, Vidyagiri, Alva's College of Physical Education, Alva's College of Physical Education, 3 3 3 M,)()dahidri 334 Vidyagiri, Moodabidri 136 Vidyagiri, Moodahidri 198 4 St.Aloysius College, Mangalore 271 4 St.Aloysius College, Mangalore 140 4 M. U.Campus, Mangalagangothri 141 M.U.L'ampus, Mangalagangothri 5 St.Philomena College, Darbc, Puttur 5 St.Agnes College, Bendore 5 266 127 132 6 St.Philomena College, Darbe, Puttur 197 6 M. U. Campus, Mangalagangothri 125 6 St.Aloysius College, Mangalore 131 Dr.B.B.Hegde First Grade College, Govt. First Grade College, GoYt. First Grade College, Vamadapadavu, Bantwal 7 7 7 196 Kundapura 97 Vamadapa<lan1, Bantwal 100 Govt. First Grade College, School of Social Work, Roshni School of Social Work, Roshni Nilaya, Mang?.lore 8 8 8 157 Vamadapadavu, Bantwal 96 Nilaya, Mangalore 81 Dr.B.B.Hegde First -

Dated : 23/4/2016

Dated : 23/4/2016 Signatory ID Name CIN Company Name Defaulting Year 01750017 DUA INDRAPAL MEHERDEEP U72200MH2008PTC184785 ALFA-I BPO SERVICES 2009-10 PRIVATE LIMITED 01750020 ARAVIND MYLSWAMY U01120TZ2008PTC014531 M J A AGRO FARMS PRIVATE 2008-09, 2009-10 LIMITED 01750025 GOYAL HEMA U18263DL1989PLC037514 LEISURE WEAR EXPORTS 2007-08 LTD. 01750030 MYLSWAMY VIGNESH U01120TZ2008PTC014532 M J V AGRO FARM PRIVATE 2008-09, 2009-10 LIMITED 01750033 HARAGADDE KUMAR U74910KA2007PTC043849 HAVEY PLACEMENT AND IT 2008-09, 2009-10 SHARATH VENKATESH SOLUTIONS (INDIA) PRIVATE 01750063 BHUPINDER DUA KAUR U72200MH2008PTC184785 ALFA-I BPO SERVICES 2009-10 PRIVATE LIMITED 01750107 GOYAL VEENA U18263DL1989PLC037514 LEISURE WEAR EXPORTS 2007-08 LTD. 01750125 ANEES SAAD U55101KA2004PTC034189 RAHMANIA HOTELS 2009-10 PRIVATE LIMITED 01750125 ANEES SAAD U15400KA2007PTC044380 FRESCO FOODS PRIVATE 2008-09, 2009-10 LIMITED 01750188 DUA INDRAPAL SINGH U72200MH2008PTC184785 ALFA-I BPO SERVICES 2009-10 PRIVATE LIMITED 01750202 KUMAR SHILENDRA U45400UP2007PTC034093 ASHOK THEKEDAR PRIVATE 2008-09, 2009-10 LIMITED 01750208 BANKTESHWAR SINGH U14101MP2004PTC016348 PASHUPATI MARBLES 2009-10 PRIVATE LIMITED 01750212 BIAPPU MADHU SREEVANI U74900TG2008PTC060703 SCALAR ENTERPRISES 2009-10 PRIVATE LIMITED 01750259 GANGAVARAM REDDY U45209TG2007PTC055883 S.K.R. INFRASTRUCTURE 2008-09, 2009-10 SUNEETHA AND PROJECTS PRIVATE 01750272 MUTHYALA RAMANA U51900TG2007PTC055758 NAGRAMAK IMPORTS AND 2008-09, 2009-10 EXPORTS PRIVATE LIMITED 01750286 DUA GAGAN NARAYAN U74120DL2007PTC169008 -

CIN Company Name Investor First Name Investor Middle Name

Note: This sheet is applicable for uploading the particulars related to the shares transferred to Investor Education and Protection Fund. Make sure that the details are in accordance with the information already provided in e-form IEPF-4. CIN L40101DL1989GOI038121 Prefill Company Name POWER GRID CORPORATION OF INDIA LIMITED Nominal value of shares 2984380.00 Validate Clear Actual Date of Investor First Investor Middle Investor Last Father/Husband Father/Husband Father/Husband Last DP Id-Client Id- Nominal value of Address Country State District Pin Code Folio Number Number of shares transfer to IEPF (DD- Name Name Name First Name Middle Name Name Account Number shares MON-YYYY) HARESH JAGJIVAN KHORASIA JAGJIVAN DEVCHAND KHORASIA 128/25, 2ND FLOOR, HAZRA ROAD, KOLKATA,INDIA KOLKATA. WESTWEST BENGAL. BENGAL KOLKATA 700026 C12010200-12010200-00021620 10 100.00 18-DEC-2017 AMBALAL PREMJIBHAI PATEL PREMJIBHAI GOVINDBHAI PATEL DEBHARI, TA - VIRPUR, DIST- KHEDA, INDIAVIRPUR GUJARAT GUJARAT VIRPUR 388260 C12010400-12010400-00008557 10 100.00 18-DEC-2017 HARI BABU CHADERIA KUDAN LAL CHANDERIA Ward No-8, Pt Dindayal Puram BalaghatIndia MADHYA PRADESHMADHYA PRADESH BALAGHAT 481001 C12010600-12010600-00114061 200 2000.00 18-DEC-2017 SUDHIR KUMAR JAIN SHRI ASHOK KUMAR JAIN HNO.:16/1249, BEHIND RAIPUR FLOURINDIA MILL FAFADIH RAIPURCHHATTISGARH CHHATTISGARH RAIPUR 492001 C12010600-12010600-00160701 100 1000.00 18-DEC-2017 RAJ DEO RAI LATE RAM BRIKSH RAI S/O LATE RAM BRICHH RAJ F NO 302 INDIAMAA ENCLAVE KOK-2 (BAT)JHARKHAND KOKAR RANCHI RANCHIRANCHI JHARKHAND -

Curriculum Vitae

Curriculum Vitae Dr Navitha Thimmaiah Assistant Professor in Economics Department of Studies in Economics & Cooperation University of Mysore Manasagangotri, Mysore-570006. E-mail: [email protected] [email protected] Specialization • Quantitative Methods to Economics (Mathematics and Statistics) • Theoretical and Applied Econometrics • Research Methodology • Microeconomics Teaching Experience •At present working as Assistant Professor in the Post graduate Department of Economics of University of Mysore – ORDER NO.ET7/117/2007-08, DATED 12th July 2007. •Deputed as Faculty (Economics & Planning) at Administrative Training Institute, Government of Karnataka, Mysore from February, 2015 to February 2017. • Vidyavardhaka First Grade College: 1999 - 2000 • Maharaja‟s College (University Constituent College): 2001-02, 2002-03 • St. Philomena‟s Degree College – 2002 - 2003 • University Evening College, Mysore University, Mysore: 2004 –2005, 2005-2006 •Faculty (Economics & Planning) at Administrative Training Institute, Government of Karnataka, Mysore from May 2006 – July 2007. •Visiting faculty: Mysore University School of Justice and Bahadur Institute of Management Studies •Resource Person: Administrative Training Institute, Karnataka Police Academy, State Institute of Urban development, State Institute of Rural development, Indian Society for Training and Development. Courses/ Parers Taught Theory of Econometrics Quantitative Methods for Economics Applied Econometrics Research Methodology International Economics Indian Economy Managerial -

Documentation of Major Medicinal Plants in Sandure of Karnataka, India

OPEN ACCESS Freely available online & Aroma l tic a in P l ic a n d t e s M Medicinal & Aromatic Plants ISSN: 2167-0412 Research Article Documentation of Major Medicinal Plants in Sandure of Karnataka, India Gowramma B1*, Kyagavi G2, Karibasamma H2 and Ramanjinaiah KM2 1Department of Biotechnology, Veerashaiva College, Bellary, Karnataka, India; 2Department of Botany, Vijayanagara Sri Krishnadevaraya University, Ballari, Karnataka, India ABSTRACT Documentation of Medicinal plants is the only way to preserve the fundamental knowledge of the plant resources for future endower. The present survey is designed to study the Medicinal plants in Swamymalai block of Yeshwantha nagar beat, Sandur, Karnataka, India. This study resulted in the documentation of 50 ethnomedicinal plants. The 50 plant species are belongs to 26 families of 46 genera. The documented families in the study area are Acanthaceae, Aloaceae, Amaranthaceae, Annonaceae, Apocyanaceae, Arecaceae, Asteraceae, Caricaceae, Combretaceae, Euphorbiaceae, Fabaceae, Lamiaceae Malvaceae, Menispermaceae, Moraceae, Moringaceae, Myrtaceae, Phyllanthaceae, Poaceae, Rhamnaceae, Rutaceae, Santalaceae, Solanaceae, Verbenaceae, Vitaceae, Zingiberaceae. The survey shows that, Fabaceae is the dominant family with 12 species. The survey also reviles that, the trees are dominant ones followed by the shrubs and Herbs. Majority of the documented plants are used against several diseases, either alone or in combination with other plants. Keywords: Ethnobotany; Ethnomedicinal plants; Family; Species INTRODUCTION geographical area. Karnataka with its unique wild habitats spread India has one of the richest plant medical traditions in the world. across the Western Ghats and the Deccan Peninsula is also the Traditional medicine and ethnobotanical information’s play an home to several endemic species of commercial importance [5]. -

RP: India: Magadi-NH 48-Dobbespet (NH-4)-Koratagere, Karnataka State

Involuntary Resettlement Assessment and Measures Resettlement Plan for AEP 1: 64C, 64D and 64E (Magadi–NH 48–Dobbespet (NH-4)–Koratagere) Document Stage: Draft for Consultation Project Number: 42513 August 2010 IND: Karnataka State Highway Improvement Project Prepared by Public Works Department, Government of Karnataka. The resettlement plan is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. i TABLE OF CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS ……………………………………iv EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ……………………………..............vi 1 CHAPTER I – PROJECT DESCRIPTION....................................................................... 1 1.1 BACKGROUND ............................................................................................................ 1 1.2 OBJECTIVES............................................................................................................... 1 1.3 PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF THE PROJECT AREA................................................... 4 1.4 PROJECT COMPONENTS ............................................................................................. 4 1.5 ROAD CONFIGURATION:.............................................................................................. 4 1.6 REALIGNMENT / BYPASSES: ........................................................................................ 4 1.7 BRIDGES AND OTHER CROSS DRAINAGE STRUCTURES:................................................ 4 1.8 ROAD SIDE DRAINAGE:.............................................................................................. -

CIN/BCIN Company/Bank Name

Note: This sheet is applicable for uploading the particulars related to the unclaimed and unpaid amount pending with company. Make sure that the details are in accordance with the information already provided in e-form IEPF-2 CIN/BCIN L24110MH1947PLC005719 Prefill Company/Bank Name PIRAMAL ENTERPRISES LIMITED Date Of AGM(DD-MON-YYYY) 30-Jul-2018 Sum of unpaid and unclaimed dividend 12034164.00 Sum of interest on matured debentures 0.00 Sum of matured deposit 0.00 Sum of interest on matured deposit 0.00 Sum of matured debentures 0.00 Sum of interest on application money due for refund 0.00 Sum of application money due for refund 0.00 Redemption amount of preference shares 0.00 Sales proceed for fractional shares 0.00 Validate Clear Proposed Date of Investor First Investor Middle Investor Last Father/Husband Father/Husband Father/Husband Last DP Id-Client Id- Amount Address Country State District Pin Code Folio Number Investment Type transfer to IEPF Name Name Name First Name Middle Name Name Account Number transferred (DD-MON-YYYY) 39A SECOND STREET SMS LAYOUT PIRA000000000BS00 Amount for unclaimed and A ALAGIRI SWAMY NA ONDIPUTHUR COIMBATORE INDIA Tamil Nadu 641016 076 unpaid dividend 300.00 09-Sep-2018 H NO 6-3-598/51/12/B IST FLR ANAND NAGAR COLONY PIRA000000000AS01 Amount for unclaimed and A AMARENDRA NA HYDERABAD INDIA Andhra Pradesh 500004 467 unpaid dividend 300.00 09-Sep-2018 7-1-28/1/A/12 PARK AVENUE PIRA000000000AS01 Amount for unclaimed and A ANJI REDDY NA AMEERPET HYDERABAD INDIA Andhra Pradesh 500016 053 unpaid dividend 1200.00 09-Sep-2018 4/104, BOMMAIKUTTAI MEDU IN300159-10771263- Amount for unclaimed and A ARIVUCHELVAN NA SELLAPPAMPATTY P. -

RP: India: Davanagere–Santhebennur–Channagiri

Involuntary Resettlement Assessment and Measures Resettlement Plan for AEP 6: 42A and 42B (Davanagere–Santhebennur–Channagiri–Ajjampura– Birur) Document Stage: Draft for Consultation Project Number: 42513 August 2010 IND: Karnataka State Highway Improvement Project Prepared by Public Works Department, Government of Karnataka. The resettlement plan is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. i TABLE OF CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS ……………………………………..1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ……………………………..............5 CHAPTER I – PROJECT DESCRIPTION ............................................................................ 19 1.1 BACKGROUND .......................................................................................................... 19 1.2 OBJECTIVES............................................................................................................. 19 1.3 PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF THE PROJECT AREA................................................... 3 1.4 PROJECT COMPONENTS ............................................................................................. 3 1.5 ROAD CONFIGURATION:.............................................................................................. 3 1.6 REALIGNMENT / BYPASSES: ........................................................................................ 3 1.7 BRIDGES AND OTHER CROSS DRAINAGE STRUCTURES:................................................ 3 1.8 ROAD SIDE -

Faculty Profile

SJM Vidyapeetha® SJM DENTAL COLLEGE AND HOSPITAL, CHITRADURGA FACULTY PROFILE A) GENERAL INFORMATION NAME Dr. GOWRAMMA .R AGE 51years SEX Female Date of Birth 04-06-1964 181/A, 1st cross, JCR Extension ADDRESS Chitradurga- 577501 Karnataka MOBILE NO: +919481721444 EMAIL ID [email protected] KSDC Reg No: 938-A B) CRITERIA WISE PROFILE 1) CURRICULAR ASPECTS QUALIFICATION BDS,MDS TEACHING EXPERIENCE 25 YEARS DESIGNATION Principal, Professor and HOD MEMBER OF BOARD OF STUDIES, RGUHS Member of Board of Studies, RGUHS 1999-2000. Present Member of Board of Studies, RGUHS. 1. One day consultative workshop on Restructuring of WORK SHOPS ATTENDED REGARDING BDS regulations- 2007 organized by RGUHS in CURRICULAR DESIGN association with DCI at Bangalore-2011. 2. Workshop on Undergraduate valuation held at RGUHS Bangalore on 4.1.2013. 3. Symposium on improving the quality of Dental education at BDCH Davanagere on 5th and 6th March 2013. 4. Orientation program on NABH Accreditation organized by RGUHS Bangalore on 21st November 2011. 2) TEACHING & LEARNING 1. Experiential Learning Lectures-4 on Ethicos for Medicos held by dept of Medical Education, SSIMS & RC, Davanagere on 23.02.2013. 2. Program on teachers motivation skill infused and FACULTY DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMES & value based education – need of the hour at SJM WORK SHOPS ATTENDED REGARDING College of Arts, Science and Commerce Chitradurga TEACHING AND LEARNING. on 07.04.2015. 3. IQMC (Institutional quality monitoring cell) at RGUHS in June 2016. 4. Symposium on improving the quality of Dental education at BDCH Davanagere on 5th and 6th March 2013. 5. Worked as paper setter for Bangalore university for undergraduates and examiner for second, third and final year BDS in various universities. -

Vulnerability Assessment of Urban Marginalised Communities: a Pilot Study in Bangalore Slum Areas

Vulnerability Assessment of Urban Marginalised Communities: A Pilot study in Bangalore Slum areas by Centre For Education & Documentation(CED) With support from Indian Network on Ethics and Climate Change (INECC) November 2010-May 2011 Indian Network on Ethics and Climate Centre for Education and Change (INECC). Documentation (CED) www.inecc.net www.doccentre.net c/o Laya, 501, Kurupam Castle, East 3 Suleman Chambers, 4 Battery Point Colony, Street, Mumbai 400001 Peda Waltair, Visakhapatnam - 530017 Vulnerability Assessment of Urban Marginalised Communities: A Pilot study in Bangalore Slum areas Advisory Group: Walter Mendoza (Chair) CED, Prof. T.G.Sitharam (Chairman, CiSTUP, IISc), Dr.H.S.Sudhira(Researcher, Gubbi Labs), Rohan D'Souza (Ph.D fellow, NIAS), Dr.Bidisha Nandy (Post-Doc fellow, IISc), Dr. Harini Nagendra(Adjunct Fellow, ATREE & Asia Research Co-ordinator, Indiana University),Vinay Baindur(Independent Researcher) are among the advisors. Other facilitators :Issac Amrutraj(Activist),Wilma Rodrigues (SAAHAS), Prema Manthesh(Ragpickers Education & Development Scheme-REDS). Report by John D’Souza Questionnaire and Research Design: Hita Unnikrishnan Researchers :Veena B N Research Assistance: Jacintha Menezes 2011 Vulnerability Assessment: Urban Areas: A Pilot study ii Table of Contents I Issues & Themes 1 I.1 Vulnerability to Climate Change in the urban context I.2 Areas of Urban Vulnerability, and Indicators I.3 Bangalore: Features of Bangalore with relation to areas of Urban Vulnerability I.4 Development and Governance of Slums in Bangalore II Methodology of the Study 8 II.1 Factors influencing methodology of the study II.2 The Process of the study II.3 Areas chosen for Study: Rationale and Process III People & Livelihood 12 IV. -

UNIVERSITY of DELHI MASTER of LAWS (2Year/3 Year) LL.M

Faculty of Law, University of Delhi UNIVERSITY OF DELHI MASTER OF LAWS (2Year/3 Year) LL.M. (2 Year/3 Year) (Effective from Academic Year ……..) PROGRAMME BROCHURE LL.M. Revised Syllabus as approved by Academic Council on XXXX, 2019 and Executive Council on YYYY, 2019 35 Department of Law, University of Delhi CONTENTS Page I. About the Department 03 II. Introduction to CBCS 05/21 Scope Definitions Programme Objectives (POs) Programme Specific Outcomes (PSOs) III. LL.M. Programme Details 06/22 Programme Structure Eligibility for Admissions Assessment of Students’ Performance and Scheme of Examination Pass Percentage & Promotion Criteria: Semester to Semester Progression Conversion of Marks into Grades Grade Points CGPA Calculation Division of Degree into Classes Attendance Requirement Span Period Guidelines for the Award of Internal Assessment Marks LL.M. Programme (Semester Wise) IV. Course Wise Content Details for LL.M. Programme 35 36 Department of Law, University of Delhi I. About the Department The Faculty of Law was established in 1924 by University of Delhi. Dr. Hari Singh Gaur, was its first Dean and was also the Vice Chancellor of the University. The Faculty of Law was initially located in the Prince's Pavilion in the Old Vice Regal Lodge Grounds. In the year 1963 it was moved to its present location on Chhatra Marg, North Campus, University of Delhi and one more building, Umang Bhawan, near the old premise on the Chhatra Marg is allotted by university of Delhi in 2015 to the Faculty of Law. In 1944, one year Master of Laws (LL.M.) was introduced. The LL.M.