Ramtanu Lahiri, Brahman and Reformer : a History of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Courses Taught at Both the Undergraduate and the Postgraduate Levels

Jadavpur University Faculty of Arts Department of History SYLLABUS Preface The Department of History, Jadavpur University, was born in August 1956 because of the Special Importance Attached to History by the National Council of Education. The necessity for reconstructing the history of humankind with special reference to India‘s glorious past was highlighted by the National Council in keeping with the traditions of this organization. The subsequent history of the Department shows that this centre of historical studies has played an important role in many areas of historical knowledge and fundamental research. As one of the best centres of historical studies in the country, the Department updates and revises its syllabi at regular intervals. It was revised last in 2008 and is again being revised in 2011.The syllabi that feature in this booklet have been updated recently in keeping with the guidelines mentioned in the booklet circulated by the UGC on ‗Model Curriculum‘. The course contents of a number of papers at both the Undergraduate and Postgraduate levels have been restructured to incorporate recent developments - political and economic - of many regions or countries as well as the trends in recent historiography. To cite just a single instance, as part of this endeavour, the Department now offers new special papers like ‗Social History of Modern India‘ and ‗History of Science and Technology‘ at the Postgraduate level. The Department is the first in Eastern India and among the few in the country, to introduce a full-scale specialization on the ‗Social History of Science and Technology‘. The Department recently qualified for SAP. -

Journal of Bengali Studies

ISSN 2277-9426 Journal of Bengali Studies Vol. 6 No. 1 The Age of Bhadralok: Bengal's Long Twentieth Century Dolpurnima 16 Phalgun 1424 1 March 2018 1 | Journal of Bengali Studies (ISSN 2277-9426) Vol. 6 No. 1 Journal of Bengali Studies (ISSN 2277-9426), Vol. 6 No. 1 Published on the Occasion of Dolpurnima, 16 Phalgun 1424 The Theme of this issue is The Age of Bhadralok: Bengal's Long Twentieth Century 2 | Journal of Bengali Studies (ISSN 2277-9426) Vol. 6 No. 1 ISSN 2277-9426 Journal of Bengali Studies Volume 6 Number 1 Dolpurnima 16 Phalgun 1424 1 March 2018 Spring Issue The Age of Bhadralok: Bengal's Long Twentieth Century Editorial Board: Tamal Dasgupta (Editor-in-Chief) Amit Shankar Saha (Editor) Mousumi Biswas Dasgupta (Editor) Sayantan Thakur (Editor) 3 | Journal of Bengali Studies (ISSN 2277-9426) Vol. 6 No. 1 Copyrights © Individual Contributors, while the Journal of Bengali Studies holds the publishing right for re-publishing the contents of the journal in future in any format, as per our terms and conditions and submission guidelines. Editorial©Tamal Dasgupta. Cover design©Tamal Dasgupta. Further, Journal of Bengali Studies is an open access, free for all e-journal and we promise to go by an Open Access Policy for readers, students, researchers and organizations as long as it remains for non-commercial purpose. However, any act of reproduction or redistribution (in any format) of this journal, or any part thereof, for commercial purpose and/or paid subscription must accompany prior written permission from the Editor, Journal of Bengali Studies. -

Landscaping India: from Colony to Postcolony

Syracuse University SURFACE English - Dissertations College of Arts and Sciences 8-2013 Landscaping India: From Colony to Postcolony Sandeep Banerjee Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/eng_etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, Geography Commons, and the South and Southeast Asian Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Banerjee, Sandeep, "Landscaping India: From Colony to Postcolony" (2013). English - Dissertations. 65. https://surface.syr.edu/eng_etd/65 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts and Sciences at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in English - Dissertations by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT Landscaping India investigates the use of landscapes in colonial and anti-colonial representations of India from the mid-nineteenth to the early-twentieth centuries. It examines literary and cultural texts in addition to, and along with, “non-literary” documents such as departmental and census reports published by the British Indian government, popular geography texts and text-books, travel guides, private journals, and newspaper reportage to develop a wider interpretative context for literary and cultural analysis of colonialism in South Asia. Drawing of materialist theorizations of “landscape” developed in the disciplines of geography, literary and cultural studies, and art history, Landscaping India examines the colonial landscape as a product of colonial hegemony, as well as a process of constructing, maintaining and challenging it. In so doing, it illuminates the conditions of possibility for, and the historico-geographical processes that structure, the production of the Indian nation. -

Radhanath Sikdar First Scientist of Modern India Dr

R.N. 70269/98 Postal Registration No.: DL-SW-1/4082/12-14 ISSN : 0972-169X Date of posting: 26-27 of advance month Date of publication: 24 of advance month July 2013 Vol. 15 No. 10 Rs. 5.00 Maria Goeppert-Mayer The Second Woman Nobel Laureate in Physics Puzzles and paradoxes (1906-1972) Editorial: Some important facets 35 of Science Communications Maria Goeppert-Mayer: The 34 Second Woman Nobel Laureate in Physics Puzzles and paradoxes 31 Radhanath Sikdar: First 28 Scientist of Modern India Surgical Options for a Benign 25 Prostate Enlargement Recent developments 22 in science and technology VP News 19 Editorial Some important facets of Science Communications Dr. R. Gopichandran recent White Paper by Hampson (2012)1 presents an insightful forums for coming together including informal settings appear to Aanalysis of the process and impacts of science communication. help fulfil communication goals. These are also directly relevant The author indicates that the faith of the public in science is to informal yet conducive learning environment in rural areas modulated by the process and outcome of communicating science, of India and hence the opportunity to further strengthen such with significant importance attributed to understanding the needs interactions. and expectations from science by communities. Hampson also Bultitude (2011)3 presents an excellent overview of the highlights the need to improve communication through systematic “Why and how of Science Communication” with special reference and logical guidance to institutions to deliver appropriately. This to the motivation to cater to specific needs of the end users of deficit also negatively impacts engagement amongst stakeholders. -

Readily Available, Such Studies Are More Broad-Based Now Than They Were in 1990S, When Such Comparative Performances First Surfaced

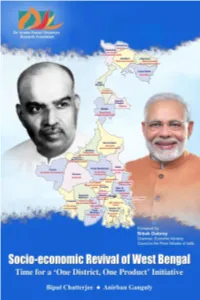

Shri Bipul Chatterjee Executive Director, CUTS International, Jaipur Dr. Anirban Ganguly Director, Dr. Syama Prasad Mookerjee Research Foundation, New Delhi Date of Publication September 2020 This document has been prepared with research assistance from a group of young researchers. They are: Sumanta Biswas, Bijaya Roy, Dipanwita Chatterjee and Sudip Kumar Paul. They have contributed in their personal capacity. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Foreword 4 2. Prologue 7 3. Introduction 10 4. A Snapshot of ‘One District, One Product’ 15 5. Conclusion 35 6. Epilogue 40 3 Foreword tates are natural administrative units. Therefore, often, there are inter-State studies, comparing S economic performance and governance across States. With much more data readily available, such studies are more broad-based now than they were in 1990s, when such comparative performances first surfaced. Once upon a time, they used to be based on notions of GSDP (gross State domestic product) or its variations, with perhaps something like poverty rates thrown in. Today, variables straddle a range of physical and social infrastructure heads, with law and order also occasionally thrown in. Therefore, the issue of convergence versus divergence across States is a bit of a non-starter. The answer depends on the variable used and weights used to construct an index. Since some States have had a head- start, the answer also depends on whether one considers absolute values, or increments to those. Small States and Union Territories are often in a different basket. Therefore, there is greater interest in larger States (defined both as population and geographical area), since larger shares of population reside there. -

Reflections of Bengali Subaltern Society and Cultural Identity Through the Bangali Bhadrolok’S Lenses: an Analysis

Parishodh Journal ISSN NO:2347-6648 Reflections Of Bengali Subaltern Society And Cultural IdentIty through the BangalI Bhadrolok’s lenses: an Analysis -Mithun Majumder Phd Research scholar, Deptt of International Relations, Jadavpur University Abstract The Bengalis are identified as culture savvy race, at the national and international levels. But if one dwells deep into Bengali culture, one may identify an admixture of elite/ higher class culture with typical lower/subaltern class culture. Often, it has been witnessed that elite/upper class culture has influenced subaltern class culture. This essay attempts to analyze such issues like: How is the position of the subaltern class reflected in typical elite class mindset? How do they define the subaltern class? Is Bengali culture dominated by the elite class only or the subaltern class gets priority as the chief producer class? This essay strives to answer many such questions Key Words: Bhadralok, Subalterns, Culture, Class, Race, JanaJati By Bengali society and cultural identity, one does mean the construction of a typical Bhadralok cultural identity and Kolkata is identified as the epicentre of Bengali Bhadralok culture. But the educated middle class city residents, salaried people, intellectuals also represent this culture. Bengali art and literature and the ideas generated from the civil society in Kolkata and its cultural exchanges with typical Mofussil or rural subaltern culture can lead to the construction of new language or dialect and may even lead to deconstruction of the same. The unorganized rural women labourers(mostly working as domestic help) often use the phrase that “ we work in Baboo homes in Kolkata”. -

A Hermeneutic Study of Bengali Modernism

Modern Intellectual History http://journals.cambridge.org/MIH Additional services for Modern Intellectual History: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here FROM IMPERIAL TO INTERNATIONAL HORIZONS: A HERMENEUTIC STUDY OF BENGALI MODERNISM KRIS MANJAPRA Modern Intellectual History / Volume 8 / Issue 02 / August 2011, pp 327 359 DOI: 10.1017/S1479244311000217, Published online: 28 July 2011 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S1479244311000217 How to cite this article: KRIS MANJAPRA (2011). FROM IMPERIAL TO INTERNATIONAL HORIZONS: A HERMENEUTIC STUDY OF BENGALI MODERNISM. Modern Intellectual History, 8, pp 327359 doi:10.1017/S1479244311000217 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/MIH, IP address: 130.64.2.235 on 25 Oct 2012 Modern Intellectual History, 8, 2 (2011), pp. 327–359 C Cambridge University Press 2011 doi:10.1017/S1479244311000217 from imperial to international horizons: a hermeneutic study of bengali modernism∗ kris manjapra Department of History, Tufts University Email: [email protected] This essay provides a close study of the international horizons of Kallol, a Bengali literary journal, published in post-World War I Calcutta. It uncovers a historical pattern of Bengali intellectual life that marked the period from the 1870stothe1920s, whereby an imperial imagination was transformed into an international one, as a generation of intellectuals born between 1885 and 1905 reinvented the political category of “youth”. Hermeneutics, as a philosophically informed study of how meaning is created through conversation, and grounded in this essay in the thought of Hans Georg Gadamer, helps to reveal this pattern. -

Raja Ram Mohan Roy (1772 — 1833)

UNIT – II SOCIAL THINKERS RAJA RAM MOHAN ROY (1772 — 1833) Introduction: Raja Ram Mohan Roy was a great socio-religious reformer. He was born in a Brahmin family on 10th May, 1772 at Radhanagar, in Hoogly district of Bengal (now West Bengal). Ramakanto Roy was his father. His mother’s name was Tarini. He was one of the key personalities of “Bengal Renaissance”. He is known as the “Father of Indian Renaissance”. He re- introduced the Vedic philosophies, particularly the Vedanta from the ancient Hindu texts of Upanishads. He made a successful attempt to modernize the Indian society. Life Raja Ram Mohan Roy was born on 22 May 1772 in an orthodox Brahman family at Radhanagar in Bengal. Ram Mohan Roy’s early education included the study of Persian and Arabic at Patna where he read the Quran, the works of Sufi mystic poets and the Arabic translation of the works of Plato and Aristotle. In Benaras, he studied Sanskrit and read Vedas and Upnishads. Returning to his village, at the age of sixteen, he wrote a rational critique of Hindu idol worship. From 1803 to 1814, he worked for East India Company as the personal diwan first of Woodforde and then of Digby. In 1814, he resigned from his job and moved to Calcutta in order to devote his life to religious, social and political reforms. In November 1930, he sailed for England to be present there to counteract the possible nullification of the Act banning Sati. Ram Mohan Roy was given the title of ‘Raja’ by the titular Mughal Emperor of Delhi, Akbar II whose grievances the former was to present 1/5 before the British king. -

Setting the Stage: a Materialist Semiotic Analysis Of

SETTING THE STAGE: A MATERIALIST SEMIOTIC ANALYSIS OF CONTEMPORARY BENGALI GROUP THEATRE FROM KOLKATA, INDIA by ARNAB BANERJI (Under the Direction of Farley Richmond) ABSTRACT This dissertation studies select performance examples from various group theatre companies in Kolkata, India during a fieldwork conducted in Kolkata between August 2012 and July 2013 using the materialist semiotic performance analysis. Research into Bengali group theatre has overlooked the effect of the conditions of production and reception on meaning making in theatre. Extant research focuses on the history of the group theatre, individuals, groups, and the socially conscious and political nature of this theatre. The unique nature of this theatre culture (or any other theatre culture) can only be understood fully if the conditions within which such theatre is produced and received studied along with the performance event itself. This dissertation is an attempt to fill this lacuna in Bengali group theatre scholarship. Materialist semiotic performance analysis serves as the theoretical framework for this study. The materialist semiotic performance analysis is a theoretical tool that examines the theatre event by locating it within definite material conditions of production and reception like organization, funding, training, availability of spaces and the public discourse on theatre. The data presented in this dissertation was gathered in Kolkata using: auto-ethnography, participant observation, sample survey, and archival research. The conditions of production and reception are each examined and presented in isolation followed by case studies. The case studies bring the elements studied in the preceding section together to demonstrate how they function together in a performance event. The studies represent the vast array of theatre in Kolkata and allow the findings from the second part of the dissertation to be tested across a variety of conditions of production and reception. -

The Black Hole of Empire

Th e Black Hole of Empire Th e Black Hole of Empire History of a Global Practice of Power Partha Chatterjee Princeton University Press Princeton and Oxford Copyright © 2012 by Princeton University Press Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to Permissions, Princeton University Press Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540 In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW press.princeton.edu All Rights Reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Chatterjee, Partha, 1947- Th e black hole of empire : history of a global practice of power / Partha Chatterjee. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-691-15200-4 (hardcover : alk. paper)— ISBN 978-0-691-15201-1 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Bengal (India)—Colonization—History—18th century. 2. Black Hole Incident, Calcutta, India, 1756. 3. East India Company—History—18th century. 4. Imperialism—History. 5. Europe—Colonies—History. I. Title. DS465.C53 2011 954'.14029—dc23 2011028355 British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available Th is book has been composed in Adobe Caslon Pro Printed on acid-free paper. ∞ Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 To the amazing surgeons and physicians who have kept me alive and working This page intentionally left blank Contents List of Illustrations ix Preface xi Chapter One Outrage in Calcutta 1 Th e Travels of a Monument—Old Fort William—A New Nawab—Th e Fall -

Indian Response to Western Science Hari Babu Boddu Assistant

Indian Response to Western Science Hari Babu Boddu Assistant Professor P. G. Department of History Magadh University It may be no more than a coincidence that the British merchant ships arrived in India the same year (1608) telescope was invented in the Netherlands. But it does bring home the fact that modern science and technology have grown hand in hand with maritime activity, colonial expansion and Western domination over nature and fellow human beings. The British could not have built and retained an empire in India without the help of science and the natives. This brought Indians in touch with modern science. The phenomenon can be conveniently discussed in terms of a three-stage model comprising the colonial-tool stage, the peripheral-native stage, and the Indian response stage, each leading to and coexisting with the next (Kochhar 1992, 1993). The colonial-tool stage began with field surveys and went on to include technologies such as steam, telegraph, railway and radio. The Western scientific interest in the subcontinent was latitude- driven in the sense that it was dictated by the geographical and ecological novelty of India. (In contrast the current software-facilitated globalization – era Western interest in India is longitude- driven.) The institutionalization of science as a colonial tool began in 1767 with the appointment of a surveyor-general in Bengal (Phillimore 1945 I : 2). Ironically when we celebrate anniversaries of scientific institutions like the Trigonometrical Survey, Geological Survey or railways we are also unwittingly celebrating step-wise entrenchment of the British in India. The peripheral-native stage can be taken to have begun in 1817 with the founding of the Hindoo College in Calcutta (see below). -

Empire's Garden: Assam and the Making of India

A book in the series Radical Perspectives a radical history review book series Series editors: Daniel J. Walkowitz, New York University Barbara Weinstein, New York University History, as radical historians have long observed, cannot be severed from authorial subjectivity, indeed from politics. Political concerns animate the questions we ask, the subjects on which we write. For over thirty years the Radical History Review has led in nurturing and advancing politically engaged historical research. Radical Perspec- tives seeks to further the journal’s mission: any author wishing to be in the series makes a self-conscious decision to associate her or his work with a radical perspective. To be sure, many of us are currently struggling with the issue of what it means to be a radical historian in the early twenty-first century, and this series is intended to provide some signposts for what we would judge to be radical history. It will o√er innovative ways of telling stories from multiple perspectives; comparative, transnational, and global histories that transcend con- ventional boundaries of region and nation; works that elaborate on the implications of the postcolonial move to ‘‘provincialize Eu- rope’’; studies of the public in and of the past, including those that consider the commodification of the past; histories that explore the intersection of identities such as gender, race, class and sexuality with an eye to their political implications and complications. Above all, this book series seeks to create an important intellectual space and discursive community to explore the very issue of what con- stitutes radical history. Within this context, some of the books pub- lished in the series may privilege alternative and oppositional politi- cal cultures, but all will be concerned with the way power is con- stituted, contested, used, and abused.