Front Matter Template

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

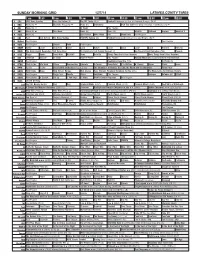

Sunday Morning Grid 12/7/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 12/7/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Pittsburgh Steelers at Cincinnati Bengals. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News (N) Swimming PGA Tour Golf Hero World Challenge, Final Round. (N) Å 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) Wildlife Outback Explore World of X 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Indianapolis Colts at Cleveland Browns. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR The Omni Health Revolution With Tana Amen Dr. Fuhrman’s End Dieting Forever! Å Joy Bauer’s Food Remedies (TVG) Deepak 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Things That Aren’t Here Anymore More Things Aren’t Here Anymore 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program Holiday Heist (2011) Lacey Chabert, Rick Malambri. 34 KMEX Paid Program República Deportiva (TVG) Al Punto (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Tu Dia Tu Dia Beverly Hills Chihuahua 2 (2011) (G) The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe Fútbol MLS 50 KOCE Wild Kratts Maya Rick Steves’ Europe Rick Steves Suze Orman’s Financial Solutions for You (TVG) The Roosevelts: An Intimate History 52 KVEA Paid Program Raggs New. -

CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION A. Background of the Study People

CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION A. Background of the Study People live in the world in various cultures. They live in different co mmunity and background. They are different, and they often have problems in their live. Life becomes more complex as more problems appear. They are having the same opportunity to get their property, prosperity and happiness. They must work hard and struggle to get such things. According to Meizeir (http: // www. self growth. com/ article/ Meizeir. html) “Struggle is any personal goal achievement accompanied by discomfort and resistance. Struggle may still certainly involve overcoming resistance and discomfort”. Struggle is identical wit h hero and it is a symbol of freedom of a nation to fight against the colonialism. It has a general meaning as a way to get the best result and something worth. People will do everything to get it. This occurs in many kinds of field, one of them in literary works. Literature is an artwork while has idea of struggle elements such as novel, poetry, and film. Film has the same position in textual studies. It is true that film has become part of daily life, which is more complicated than the other works. Making a film is not like writing a novel. It needs a teamwork, which involves many people as crew. Film has many elements, such as director, script, writer, editor, music composer, artistic , costume, designer, etc. 2 Beside that, it also needs some technique including cinematography, editing, and sound. There are many aspects of literature that describe our daily life and our surrounding such as struggle, effort, etc. -

Ghost Hunting

Haunted house in Toledo Ghost Hunting GHOST HUNTING 101 GHOST HUNTING 102 This course is designed to give you a deeper insight into the This course is an extended version of Ghost Hunting 101. While world of paranormal investigation. Essential characteristics of it is advised that Ghost hunting 101 be taken as a prerequisite, it a paranormal investigation require is not necessary. This class will expand on topics of paranormal a cautious approach backed up investigations covered in the first class. It will also cover a variety with scientific methodology. Learn of topics of interest to more experienced investigators, as well as, best practices for ghost hunting, exploring actual techniques for using equipment in ghost hunting, investigating, reviewing evidence and types of hauntings, case scenarios, identifying the more obscure presenting evidence to your client. Learn spirits and how to deal with them along with advanced self- from veteran paranormal investigator protection. Learn from veteran paranormal investigator, Harold Harold St. John, founder of Toledo Ohio St. John, founder of the Toledo Ohio Ghost Hunters Society. If you Ghost Hunters Society. We will study have taken Ghost Hunting 101 and have had an investigation, you the different types of haunting's, a might want to bring your documented evidence such as pictures, typical case study of a "Haunting", the EVP’s or video to share with your classmates. There will be three Harold St. John essential investigating equipment, the classes of lecture and discussions with the last session being a investigation process and how to deal field trip to hone the skills you have learned. -

Texas Paranormalists

! TEXAS PARANORMALISTS David!Goodman,!B.F.A,!M.A.! ! ! Thesis!Prepared!for!the!Degree!of! MASTER!OF!FINE!ARTS! ! ! UNIVERSITY!OF!NORTH!TEXAS! December!2015! ! APPROVED:!! Tania!Khalaf,!Major!Professor!!!!! ! Eugene!Martin,!Committee!Member!&!!!! ! Chair!for!the!Department!of!Media!Arts ! Marina!Levina,!Committee!Member!!!! ! Goodman, David. “Texas Paranormalists.” Master of Fine Arts (Documentary Production and Studies), December 2015, 52 pp., references, 12 titles. Texas Pararnormalists mixes participatory and observational styles in an effort to portray a small community of paranormal practitioners who live and work in and around North Texas. These practitioners include psychics, ghost investigators, and other enthusiasts and seekers of the spirit world. Through the documentation of their combined perspectives, Texas Paranormalists renders a portrait of a community of outsiders with a shared belief system and an unshakeable passion for reaching out into the unknown. ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Copyright!2015! By! David!Goodman! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ii! ! Table!of!Contents! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !!!! !!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!Page! PROSPECTUS………………………………………………………………………………………………………!1! Introduction!and!Description……………………………………………………………………..1! ! Purpose…………………………………………………………………………………………….………3! ! Intended!Audience…………………………………………………………………………………….4! ! Preproduction!Research…….....................…………………………………………...…………..6! ! ! Feasibility……...……………...…………….………………………………………………6! ! ! Research!Summary…….…...…..……….………………………………………………7! Books………...………………………………………………………………………………..8! -

Cinematic Ghosts: Haunting and Spectrality from Silent Cinema to the Digital Era

Cinematic Ghosts: Haunting and Spectrality from Silent Cinema to the Digital Era. Edited by Murray Leeder. Bloomsbury Academic, 2015 (307 pages). Anton Karl Kozlovic Murray Leeder’s exciting new book sits comfortably alongside The Haunted Screen: Ghosts in Literature & Film (Kovacs), Ghost Images: Cinema of the Afterlife (Ruffles), Dark Places: The Haunted House in Film (Curtis), Popular Ghosts: The Haunted Spaces of Everyday Culture (Blanco and Peeren), The Spectralities Reader: Ghost and Haunting in Contemporary Cultural Theory (Blanco and Peeren), The Ghostly and the Ghosted in Literature and Film: Spectral Identities (Kröger and Anderson), and The Spectral Metaphor: Living Ghosts and the Agency of Invisibility (Peeren) amongst others. Within his Introduction Leeder claims that “[g]hosts have been with cinema since its first days” (4), that “cinematic double exposures, [were] the first conventional strategy for displaying ghosts on screen” (5), and that “[c]inema does not need to depict ghosts to be ghostly and haunted” (3). However, despite the above-listed texts and his own reference list (9–10), Leeder somewhat surprisingly goes on to claim that “this volume marks the first collection of essays specifically about cinematic ghosts” (9), and that the “principal focus here is on films featuring ‘non-figurative ghosts’—that is, ghosts supposed, at least diegetically, to be ‘real’— in contrast to ‘figurative ghosts’” (10). In what follows, his collection of fifteen essays is divided across three main parts chronologically examining the phenomenon. Part One of the book is devoted to the ghosts of precinema and silent cinema. In Chapter One, “Phantom Images and Modern Manifestations: Spirit Photography, Magic Theater, Trick Films, and Photography’s Uncanny”, Tom Gunning links “Freud’s uncanny, the hope to use modern technology to overcoming [sic] death or contact the afterlife, and the technologies and practices that led to cinema” (10). -

A-Z-Movies-November-2020.Pdf

NOVEMBER 2020 A-Z MOVIES 1% (MA 15+ a) missing father and unravel Mel Gibson, Robert Downey Jr MOVIES THRILLER 2006 Drama their high school reunion. Having MOVIES PREMIERE 2017 November 9, 15, 21 a mystery that threatens the A young pilot is unwittingly recruited (MA 15+ dlsv) decided to spend the weekend Drama (MA 15+ alsv) James Franco, Kate Mara. survival of our planet. into a covert and corrupt CIA November 2, 3, 15, 26 together reconnecting, they try to November 11 Trapped under a boulder, a mountain organisation transporting illicit goods Justin Timberlake, Emile Hirsch. recapture the glories of their youth. Matt Nable, Ryan Corr. climber faces the elements, death and ADAPTATION in and out of Southeast Asia during the When an arrogant young drug dealer The heir to the throne of a notorious his own demons before making the DRAMA MOVIES 2002 Vietnam war. kidnaps the brother of a client the AMERICAN SNIPER outlaw motorcycle club must betray grisliest decision of his life. Comedy (MA 15+ ad) situation quickly spirals out of control. DRAMA MOVIES 2014 his president to save his brother’s life. November 25 AIR BUD: Action/Adventure (MA 15+ av) 1941 Nicolas Cage, Meryl Streep. GOLDEN RECEIVER AMANDa KNOX: November 4, 11, 23, 26 8 MILE MOVIES GREATS 1979 Comedy (M s) The real and fictional intertwine in an MOVIES KIDS 1998 Family Murder ON TRIAL IN ITALY Bradley Cooper, Sienna Miller. DRAMA MOVIES 2002 Drama (M alsv) November 3, 12, 19, 30 explosive bid for survival between November 1, 6 LIFETIME MOVIES 2011 A Navy SEAL’s pinpoint accuracy saves November 2, 9, 12, 24 Dan Aykroyd, John Belushi. -

Spiritualism and Social Conflict in Late Imperial Russia

Mysterious knocks, flying potatoes and rebellious servants: Spiritualism and social conflict in late Imperial Russia Julia Mannherz1 (Oriel College Oxford) Strange things occurred in the night of 13 December, 1884, in the city of Kazan on the river Volga. As Volzhskii vestnik (The Volga Herald) reported, unidentifiable raps were heard in the flat rented by the retired officer Florentsov on Srednaia Iamskaia Street. Before the newspaper described what had actually been observed, it made it clear that ‘all descriptions here are true facts, as has been ascertained by a member of our newspaper’s editorial board’. This assertion was deemed necessary because the phenomena were of a kind ‘regarded as “inexplicable”‘. On the evening of 13 December: Mr. Florentsov was just about to go to bed, when a loud rap on his apartment’s ceiling was heard, which caused worry even to the neighbours. At about the same time, potatoes and bricks began to fly out of the oven pipe and smashed the kitchen window. On the 14th the ‘phenomena’ continued all day long and were accompanied by many comical episodes. About 10 well-known officers came to Mr. Florentsov’s apartment. They put a heavy pole against the oven-door, but the shaft was not strong enough and it soon flew to one side. [After this] potatoes rolled out beneath the furniture, fell from the walls, rained down from the ceiling; sometimes a brick appeared at the scene of action. One officer was hit by a potato on his head, another one on his nose, some were hit by the bullets of this invisible foe at their backs, shoulders and so on. -

Assignment 3 1/21/2015

Assignment 3 1/21/2015 The University of Wollongong School of Computer Science and Software Engineering CSCI124/MCS9124 Applied Programming Spring 2010 Assignment 3 (worth 6 marks) • Due at 11.59pm Thursday, September 9 (Week 7). Aim: Developing programs with dynamic memory and hashing. Requirements: This assignment involves the development of a database for a cinema. The program is designed to look up past movie releases, determining when the film was released, the rating it received from the Classification Board and its running time. To accelerate the lookup, a hash table will be used, with two possible hash functions. The program will report how efficiently the table is operating. Storage will be dynamic, enabling the space used by the program to be adjusted to suit the datafile size. The program must clean up after memory usage. During development, the program may ignore the dynamic nature until the program is working. As an addendum, the assignment also involves the use of compiler directives and makefiles. Those students who use a platform other than Linux/Unix will be required to ensure that their programs comply with the specifications below. The program is to be implemented in three files: ass3.cpp contains the simplest form of main function, hash.h contains the function prototypes of the publicly accessible functions, where the implementations of these functions will be placed in the file hash.cpp. The first two files should not be altered, although you may write your own driver programs to test your functions during development. The third file contains the stubs of the four public functions, plus a sample struct for holding the records, usable until they are changed for dynamic memory. -

The Amityville Horror, by Jay Anson. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J., 1977

The Amityville Horror, by Jay Anson. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J., 1977. 201 pages, $7.95. Reviewed by Robert L. Morris This book claims to be the true account of a month of terrifying "paranormal" events that occurred to a Long Island family when they moved into a house in Amityville, New York, that had been the scene of a mass murder. Throughout the book there are strong suggestions that the events were demonic in origin. On the copyright page, the Library of Congress subject listings are "1. Demon- ology—Case studies. 2. Psychical research—United States—Case studies." The next page contains the following statement: "The names of several individuals mentioned in this book have been changed to protect their privacy. However, all facts and events, as far as we have been able to verify them, are strictly accurate." The front cover of the book's dust jacket contains the words: "A True Story." A close reading, plus a knowledge of details that later emerged, suggests that this book would be more appropriately indexed under "Fiction—Fantasy and horror." In fact it is almost a textbook illustration of bad investigative jour- nalism, made especially onerous by its potential to terrify and mislead people and to serve as a form of religious propaganda. To explore this in detail, we first need an outline of the events that supposed- ly took place, as described in the text of the book, plus a prologue derived from a segment of a New York television show about the case. On November 13, 1974, Ronald DeFeo shot to death six members of his family at their home in Amityville. -

LEASK-DISSERTATION-2020.Pdf (1.565Mb)

WRAITHS AND WHITE MEN: THE IMPACT OF PRIVILEGE ON PARANORMAL REALITY TELEVISION by ANTARES RUSSELL LEASK DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Texas at Arlington August, 2020 Arlington, Texas Supervising Committee: Timothy Morris, Supervising Professor Neill Matheson Timothy Richardson Copyright by Antares Russell Leask 2020 Leask iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS • I thank my Supervising Committee for being patient on this journey which took much more time than expected. • I thank Dr. Tim Morris, my Supervising Professor, for always answering my emails, no matter how many years apart, with kindness and understanding. I would also like to thank his demon kitten for providing the proper haunted atmosphere at my defense. • I thank Dr. Neill Matheson for the ghostly inspiration of his Gothic Literature class and for helping me return to the program. • I thank Dr. Tim Richardson for using his class to teach us how to write a conference proposal and deliver a conference paper – knowledge I have put to good use! • I thank my high school senior English teacher, Dr. Nancy Myers. It’s probably an urban legend of my own creating that you told us “when you have a Ph.D. in English you can talk to me,” but it has been a lifetime motivating force. • I thank Dr. Susan Hekman, who told me my talent was being able to use pop culture to explain philosophy. It continues to be my superpower. • I thank Rebecca Stone Gordon for the many motivating and inspiring conversations and collaborations. • I thank Tiffany A. -

Cinemeducation Movies Have Long Been Utilized to Highlight Varied

Cinemeducation Movies have long been utilized to highlight varied areas in the field of psychiatry, including the role of the psychiatrist, issues in medical ethics, and the stigma toward people with mental illness. Furthermore, courses designed to teach psychopathology to trainees have traditionally used examples from art and literature to emphasize major teaching points. The integration of creative methods to teach psychiatry residents is essential as course directors are met with the challenge of captivating trainees with increasing demands on time and resources. Teachers must continue to strive to create learning environments that give residents opportunities to apply, analyze, synthesize, and evaluate information (1). To reach this goal, the use of film for teaching may have advantages over traditional didactics. Films are efficient, as they present a controlled patient scenario that can be used repeatedly from year to year. Psychiatry residency curricula that have incorporated viewing contemporary films were found to be useful and enjoyable pertaining to the field of psychiatry in general (2) as well as specific issues within psychiatry, such as acculturation (3). The construction of a formal movie club has also been shown to be a novel way to teach psychiatry residents various aspects of psychiatry (4). Introducing REDRUMTM Building on Kalra et al. (4), we created REDRUMTM (Reviewing [Mental] Disorders with a Reverent Understanding of the Macabre), a Psychopathology curriculum for PGY-1 and -2 residents at Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School. REDRUMTM teaches topics in mental illnesses by use of the horror genre. We chose this genre in part because of its immense popularity; the tropes that are portrayed resonate with people at an unconscious level. -

A Haunted Genre: a Study of Ghost Hunting Reality Television

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Undergraduate Honors Theses Honors College 2018 A Haunted Genre: A Study of Ghost Hunting Reality Television Abigail L. Carlin Follow this and additional works at: https://thekeep.eiu.edu/honors_theses Part of the Television Commons A Haunted Genre: A Study of Ghost Hunting Reality Television (TITLE) BY Abigail L. Carlin UNDERGRADUATE THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS OF UNDERGRADUATE DEPARTMENTAL HONORS DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH, ALONG WITH THE HONORS COLLEGE, EASTERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY CHARLESTON, ILLINOIS 2018 YEAR I HEREBY RECOMMEND THIS UNDERGRADUATE THESIS BE ACCEPTED AS FULFILLING THE THESIS REQUIREMENT FOR UNDERGRADUATE DEPARTMENTAL HONORS DATE 'fHESISADVISOR DATE H6NORS COORDINATOR Carlin 2 Introduction to Thesis In a recent interview on CONAN, the Chicago comedian Kyle Kinane shared his opinion regarding the relationship between white privilege and the existence of ghosts. Kinane joked that he thinks "the only people who believe in poltergeists are people who don't have any real-world problems," and following that statement, he states that believing in ghosts and engaging in paranormal culture is stereotypically "white" (0:39-1:20). The parallel drawn between daily life andthe topic of race is referredto as privilege, and Kinane insinuates that white privilege leaves an individual with a significant amount of free time and resources to engage in seemingly illogical beliefs, such as ghosts; however, ghost hunting reality television lends itself to more thanboredom, as it is a new and exciting genre specific to the 21st century. In this thesis, ghost hunting reality television is explored and recognized as a cultural artifact. Born from the combination of secular methodology, religion, and technology, an unlikely and obscure genre explodes from obscurity to popular culture to such a degree that tier one celebrities, such as Post Malone, guest star on longstanding ghost hunting reality show Ghost Adventures (2008-present).