The Hidden Secrets of Copper Alloy Artifacts in the Athenian Agora

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unit: Stoichiometry Lesson: #10 Topics: Solvay Process

Unit: Stoichiometry Lesson: #10 Topics: Solvay Process The Solvay Process: A Case Study Many important industrial processes involve chemical reactions that are difficult to perform and still be economically feasible. In some cases, the overall process must follow a series of reaction steps. Sodium carbonate is a chemical that is needed in large amounts – it is used in the production of glass and soap. Historically, sodium carbonate was produced by burning plants or coal and mixing the ashes with water This method was both inefficient and very expensive because of the large amount of material that needed to be burned. The Solvay process was developed as a cost effective alternative. It involves a series of reaction steps and has a net reaction of: CaCO3 (s) + 2 NaCl (aq) Na2CO3 (aq) + CaCl2 (aq) A net reaction is determined by looking at the various reaction steps and eliminating any chemical that appears as both a reactant and a product in the various steps. These chemicals are known as intermediates. Step 1: Calcium carbonate (limestone) is decomposed by heat to form calcium oxide (lime) and carbon dioxide. CaCO3 (s) CaO (s) + CO2 (g) Step 2: Carbon dioxide reacts with aqueous ammonia and water to form aqueous ammonium hydrogen carbonate. CO2 (g) + NH3 (aq) + H2O (l) NH4HCO3 (aq) Step 3: The aqueous ammonium hydrogen carbonate reacts with sodium chloride to produce ammonium chloride and solid baking soda. NH4HCO3 (aq) + NaCl (aq) NH4Cl (aq) + NaHCO3 (s) Step 4: The baking soda is heated up and decomposed into sodium carbonate, water vapor and carbon dioxide. 2 NaHCO3 (s) Na2CO3 (s) + H2O (g) + CO2 (g) Step 5: The lime that was produced in the first step is mixed with water to produce slaked lime (calcium hydroxide). -

The Reaction of Calcium Chloride with Carbonate Salts

The Reaction of Calcium Chloride with Carbonate Salts PRE-LAB ASSIGNMENT: Reading: Chapter 3 & Chapter 4, sections 1-3 in Brown, LeMay, Bursten, & Murphy. 1. What product(s) might be expected to form when solid lithium carbonate is added to an aqueous solution of calcium chloride? Write a balanced chemical equation for this process. 2. How many grams of lithium carbonate would you need to fully react with one mole of calcium chloride? Please show your work. INTRODUCTION: The purpose of this lab is to help you discover the relationships between the reactants and products in a precipitation reaction. In this lab you will react a calcium chloride solution with lithium carbonate, sodium carbonate, or potassium carbonate. The precipitate that results will be filtered and weighed. In each determination you will use the same amount of calcium chloride and different amounts of your carbonate salt. This experiment is a "discovery"- type experiment. The procedure will be carefully described, but the analysis of the data is left purposely vague. You will work in small groups to decide how best to work up the data. In the process you will have the chance to discover some principles, to use what you have learned in lecture, and to practice thinking about manipulative details and theory at the same time. Plotting your data in an appropriate manner should verify the identity of the precipitate and clarify the relationship between the amount of carbonate salt and the yield of precipitate. Predicting the formulas of ionic compounds. Compounds like calcium chloride (CaCl2) and sodium carbonate (Na2CO3) are ionic substances. -

Here the Nonspecific Term Cupreous Metals Is Used for Copper and the Alloys Such As Brass and Bronze Where Copper Predominates

CONSERVAnON OF CUPREOUS METALS Here the nonspecific term cupreous metals is used for copper and the alloys such as brass and bronze where copper predominates. In general it matters little what the specific alloy is, for they are usually treated in the same way. Care needs to be taken only when there is a high percentage of lead or tin, both of which are amphoteric metals and dissolve in alkaline solutions. There are a considerable number of chemical treatments for copper, bronze and brass, and most are not satisfactory for cupreous metals from marine sites. Consult the bibliography at the end of this section for further information. In a marine environment the two most commonly encountered copper corrosion products are cuprous chloride and cuprous sulfide. However, the mineral alterations in the copper alloys are more complex than those of just copper. Once any cupreous object is recovered and exposed to the air, it continues to corrode by a process referred to as bronze disease. Cuprous cblorides in the presence of moisture and oxygen are hydrolyzed to form hydrochloric acid and basic cupric chloride. The hydrochloric acid in turn attacks thc uncorroded metal to form more cuprous chloride. The reaction continues until no metal remains. Any conservation of chloride contaminated cupreous objects requires that I) the cuprous chlorides be removed, 2) the cuprous chlorides be converted to harmless cuprous oxide, or 3) the chemical action of the chlorides be prevented. Cbemical Cleaning Tecbniques I. ACIDS All acid treatments require a solid metal core. All acids can and will strip off corrosion layers down to bare metal and many will even etch the barc metal. -

Multianalytical Investigation and Conservation of Unique Copper Model Tools from Ancient Egyptian Dark Age

Ge-conservación Conservação | Conservation Multianalytical Investigation and Conservation of Unique Copper Model Tools from Ancient Egyptian Dark Age Manal Maher, Yussri Salem Abstract: The article presented multianalytical investigation of a unique set of copper model tools dated back to Dark Age, from the tomb of KHENNU AND APA-EM-SA-F (289) in the south of Memphis, Saqqara. Stereomicroscope was used to examine the morphology of outer surface corrosion products. Metallographic microscope was used to investigate the microstructure of the metal core and the stratigraphy of corrosion layers. SEM-EDX was used to identify the elemental composition of the objects. XRD and Raman spectroscopy were used to analyze the outer surface and the internal corrosion respectively. The microscopic investigation revealed the corrosion layers consists of external layer, under-surface layer and internal corrosion products. Cuprite, paratacamite, nantokite, atacamite, malachite and chalconatronite were identified by XRD and Raman spectroscopy as a surface and internal corrosion. SEM-EDX revealed that the case-study objects consist of copper metal without any further alloying elements. The study presented suitable treatment for these friable objects or such cases, and then presented a safe fixing procedure by a sewing technique via transparent inert threads. Keyword: Dark Age, copper model tools, first intermediate period, corrosion products, transparent inert threads Investigación multianalítica y conservación de herramientas de cobre únicas de la Edad oscura del Antiguo Egipto Resumen: El artículo presentó una investigación multianalítica de un conjunto único de herramientas de cobre que se remonta a la Edad Oscura, de la tumba de KHENNU Y APA-EM-SA-F (289) en el sur de Memphis, Saqqara. -

Sodium Laurilsulfate Used As an Excipient

9 October 2017 EMA/CHMP/351898/2014 corr. 1* Committee for Human Medicinal Products (CHMP) Sodium laurilsulfate used as an excipient Report published in support of the ‘Questions and answers on sodium laurilsulfate used as an excipient in medicinal products for human use’ (EMA/CHMP/606830/2017) * Deletion of the E number. Please see the corrected Annex for further details. 30 Churchill Place ● Canary Wharf ● London E14 5EU ● United Kingdom Telephone +44 (0)20 3660 6000 Facsimile +44 (0)20 3660 5555 Send a question via our website www.ema.europa.eu/contact An agency of the European Union © European Medicines Agency, 2018. Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. Sodium laurilsulfate used as an excipient Table of contents Executive summary ..................................................................................... 3 Introduction ................................................................................................ 4 Scientific discussion .................................................................................... 4 1. Characteristics ....................................................................................... 4 1.1 Category (function) ............................................................................................. 4 1.2 Properties........................................................................................................... 4 1.3 Use in medicinal products ..................................................................................... 5 1.4 Regulatory -

STUDENTS 2 SCIENCE Virtual Lab Experiment Precipitates

STUDENTS 2 SCIENCE Virtual Lab Experiment Precipitates An investigation of solubility and precipitation. A classroom Experiment in Kit Form for Grades 9-12 Brief Background: Students will learn the difference between reaction precipitates like the precipitation of Basic copper carBonate from the reaction of copper chloride and sodium carBonate and those that result solely from a change in solution soluBility (water vs. isopropanol). They will learn aBout precipitation in water treatment and purification and aBout the scientists who work to provide or maintain clean water for us. Additionally, students will learn that precipitates can sometimes Be redissolved By adding another chemical compound and thus carrying out an additional chemical reaction. Safety Students and teachers must wear properly fitting goggles as they prepare for, conduct, and clean up from the activities in the kit. Read and follow all safety warnings. Also review the Materials Safety Data Sheets. Students must wash their hands with soap and water after the activities. The activities described in this kit are intended for students under the direct supervision of teachers. Student kit packaged as 13 individual units for a class size of 26. Each student package is shared by 2 students. Items in each 2-student Ziploc bag: • (1) vial labeled “CuSO4” approximately 1/4 filled with cupric sulfate • (1) empty vial laBeled “CuSO4 Solution” • (1) 4-mL vial laBeled “CaCl2” containing small amount calcium chloride • (1) vial labeled “NaHCO3” (in red lettering) approximately 1/3 -

Hydrite General Product Flyer

PRODUCT OFFERING forms, trade names and a variety of certifi cations. Please call us about your specifi c chemical requirements. PRODUCTS A-Z Acetic Acid Calcium Chloride Calcium Dioctyl Phthalate Glycol Ether DPM Reduction Chemicals Acetone Hydroxide (Lime) Calcium Dipotassium Phosphate Glycol Ether EB Liquid Inorganic Salts Aluminum Brite Dips Hypochlorite Calcium (DKP) Glycol Ether EE Magnesium Bisulfi te Aluminum Chlorhydrate Phosphates Dipropylene Glycol Glycol Ether EE-AC Magnesium Chloride Aluminum Sulfate (Alum) Carboxymethyl Cellulose Disodium Phosphate Glycol Ether EM Magnesium Hydroxide Ammonium Bicarbonate Caustic Potash Dodecylbenzenesulfonic Glycol Ether EP Magnesium Oxide Ammonium Bifl uor ide Caustic Soda Acid (DDBSA) Glycol Ether PM Magnesium Phosphate Ammonium Bisulfi te Chelants Dye Fixatives Glycol Ether PM-AC Magnesium Sulfate Ammonium Chloride Chlorine Epoxy Resins HAN, Heavy Aromatic Magnesium Sulfi te Ammonium Hydroxide Chromic Acid Ethyl Acetate Naphtha Metal Finishing Products (Aqua Ammonia) Citric Acid Ethyl Alcohol Heat Transfer Fluids Methanol Ammonium Persulfate Copper Carbonate Ethylene Diamine Tetra Heptane Methyl Amyl Ketone Ammonium Phosphates Copper Cyanide Acetic Acid (EDTA) Hexane Methyl Ethyl Ketone Ammonium Sulfate Copper Sulfate Ethylene Dichloride Hexylene Glycol Methyl Isobutyl Ketone Ammonium Sulfi te Cyclohexane Ethylene Glycol HTH Methylene Chloride Mineral Anhydrous Ammonia Cyclohexanone Felt & Wire Cleaners Hydrochloric Acid Fillers Anodizing Chemicals Dairy Cleaners Ferric Chloride Hydrofluoric Acid -

Methanogenesis Rates in Acetate and Nitrate Amended Anoxic Slurries

Methanogenesis rates in acetate and nitrate amended anoxic slurries BIOS 35502: Practicum in Environmental Field Biology Patrick Revord Advisor: William West 2011 Abstract With increasing urbanization and land use changes, pollution of lakes and wetland ecosystems is imminent. Any influx of nutrients, anthropogenic or natural, can have dramatic effects on lake gas production and flux. However, the net effect of simultaneous increase of both acetate and nitrate is unknown. Methane (CH4) production was measured in anoxic sediment and water slurries amended with ammonium nitrate (NH4NO3), which has been shown to inhibit methanogenesis, and sodium acetate (CH3COONa or NaOAc), which is known to increase methanogenesis. The addition of acetate significantly increased the methanogenesis rate, but the nitrate amendment had no significant effect. The simultaneous amendment of both acetate and nitrate showed no significant increase in CH4 compared to the control, indicating that the presence of nitrate may have reduced the effect of acetate amendment. Introduction Methane, a greenhouse gas associated with global warming, continues to increase in concentration in our atmosphere. Global yearly flux of methane into the atmosphere is 566 teragrams of CH4 per year, which is more than double pre-industrial yearly flux (Solomon et al. 2007). Increasing urbanization and land-use changes contribute significantly to increased gas levels (Anderson et al. 2010, Vitousek 1994). Nutrients travel from anthropogenic sources such as wastewater treatment facilities, landfills, and agricultural plots into nearby lakes, rivers, and wetlands, causing increased primary productivity in a process known as eutrophication (Vitousek et al. 1997). The increased nutrients and productivity lead to toxic algal blooms that create products such as acetate, H2, and CO2; a nutrient-rich anoxic environment suitable for anaerobic bacteria to produce unnaturally high levels of methane and other greenhouse gases (Davis and Koop 2006, West unpublished data). -

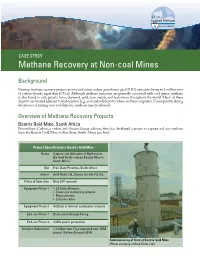

CASE STUDY Methane Recovery at Non-Coal Mines

CASE STUDY Methane Recovery at Non-coal Mines Background Existing methane recovery projects at non-coal mines reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by up to 3 million tons of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO₂e). Although methane emissions are generally associated with coal mines, methane is also found in salt, potash, trona, diamond, gold, base metals, and lead mines throughout the world. Many of these deposits are located adjacent to hydrocarbon (e.g., coal and oil) deposits where methane originates. Consequently, during the process of mining non-coal deposits, methane may be released. Overview of Methane Recovery Projects Beatrix Gold Mine, South Africa Promethium Carbon, a carbon and climate change advisory firm, has developed a project to capture and use methane from the Beatrix Gold Mine in Free State, South Africa (see box). Project Specifications: Beatrix Gold Mine Name Capture and Utilization of Methane at the Gold Fields–owned Beatrix Mine in South Africa Site Free State Province, South Africa Owner Gold Fields Ltd., Exxaro On-site Pty Ltd. Dates of Operation May 2011–present Equipment Phase 1 • GE Roots Blowers • Trolex gas monitoring systems • Flame arrestor • 23 burner flare Equipment Phase 2 Addition of internal combustion engines End-use Phase 1 Destruction through flaring End-use Phase 2 4 MW power generation Emission Reductions 1.7 million tons CO²e expected over CDM project lifetime (through 2016) Commissioning of Flare at Beatrix Gold Mine (Photo courtesy of Gold Fields Ltd.) CASE STUDY Methane Recovery at Non-coal Mines ABUTEC Mine Gas Incinerator at Green River Trona Mine (Photo courtesy of Solvay Chemicals, Inc.) Green River Trona Mine, United States Project Specifications: Green River Trona Mine Trona is an evaporite mineral mined in the United States Name Green River Trona Mine Methane as the primary source of sodium carbonate, or soda ash. -

L<Ii. Tn / CORROSION, COLORANTS, CONSERVATION the Getty

>!"li H-t> /i f-f' i'*J"i T-t i"v /S 'f -».-K' Lin-it unj»L<ii. tn / CORROSION, COLORANTS, CONSERVATION DAVID A. SCOTT The Getty Conservation Institute Los Angeles Contents xi Foreword Timothy P. Whalen xii Preface l Introduction CHAPTER 1 CORROSION AND ENVIRONMENT 11 The Anatomy of Corrosion The electrochemical series 16 Some Historical Aspects of Copper and Corrosion Primitive wet-cell batteries? Early technologies with copper and iron Early history of electrochemical plating Copper in early photography Dezincification 32 Pourbaix Diagrams and Environmental Effects The burial environment The outdoor environment The indoor museum environment The marine environment 72 Copper in Contact with Organic Materials Positive replacement and mineralization of organic materials 77 The Metallography of Corroded Copper Objects 79 Corrosion Products and Pigments CHAPTER 2 OXIDES AND HYDROXIDES 82 Cuprite Properties of cuprite Natural cuprite patinas Intentional cuprite patinas Copper colorants in glasses and glazes 95 Tenorite Tenorite formation 98 Spertiniite 98 Conservation Issues CHAPTER 3 CHAPTER 5 BASIC COPPER CARBONATES BASIC SULFATES 102 Malachite 146 Historical References to Copper Sulfates Decorative uses of malachite 147 The Basic Copper Sulfates Malachite as a copper ore Brochantite and antlerite Nomenclature confusion Posnjakite Mineral properties Other basic sulfates Malachite as a pigment Malachite in bronze patinas 154 Environment and Corrosion Isotope ratios to determine corrosion Atmospheric sulfur dioxide environment Microenvironment -

NMR Chemical Shifts of Common Laboratory Solvents As Trace Impurities

7512 J. Org. Chem. 1997, 62, 7512-7515 NMR Chemical Shifts of Common Laboratory Solvents as Trace Impurities Hugo E. Gottlieb,* Vadim Kotlyar, and Abraham Nudelman* Department of Chemistry, Bar-Ilan University, Ramat-Gan 52900, Israel Received June 27, 1997 In the course of the routine use of NMR as an aid for organic chemistry, a day-to-day problem is the identifica- tion of signals deriving from common contaminants (water, solvents, stabilizers, oils) in less-than-analyti- cally-pure samples. This data may be available in the literature, but the time involved in searching for it may be considerable. Another issue is the concentration dependence of chemical shifts (especially 1H); results obtained two or three decades ago usually refer to much Figure 1. Chemical shift of HDO as a function of tempera- more concentrated samples, and run at lower magnetic ture. fields, than today’s practice. 1 13 We therefore decided to collect H and C chemical dependent (vide infra). Also, any potential hydrogen- shifts of what are, in our experience, the most popular bond acceptor will tend to shift the water signal down- “extra peaks” in a variety of commonly used NMR field; this is particularly true for nonpolar solvents. In solvents, in the hope that this will be of assistance to contrast, in e.g. DMSO the water is already strongly the practicing chemist. hydrogen-bonded to the solvent, and solutes have only a negligible effect on its chemical shift. This is also true Experimental Section for D2O; the chemical shift of the residual HDO is very NMR spectra were taken in a Bruker DPX-300 instrument temperature-dependent (vide infra) but, maybe counter- (300.1 and 75.5 MHz for 1H and 13C, respectively). -

Experiment 1: Synthesis of Acetamides from Aniline and Substituted Anilines

Chem 216 S11 Notes - Dr. Masato Koreeda Date: May 3, 2011 Topic: __Experiment 1____ page 1 of 2. Experiment 1: Synthesis of Acetamides from Aniline and Substituted Anilines Many of the acetylated [CH3–C(=O)-] derivatives of aromatic amines (aka anilines) and phenols are pharmacologically important compounds. Some of these exhibit distinct analgesic activity. Two of the most representative examples are: H HO O N CH3 O CH3 O HO O acetaminophen (Tylenol) acetylsalicylic acid (Aspirin) ======================================================================= The reaction to be carried out in this experiment is: Acetylation of aniline δ- H3C δ+ O acetic O O anhydride H N CH3 N H (electrophile) HO O CH3 + H O CH3 acetanilide acetic acid aniline (nucleophile) Both aniline and acetic anhydride are somewhat viscous liquids. So, simply mixing them together does not result in the efficient formation of acetanilide. Therefore, a solvent (in this case water) is used to dissolve and evenly disperse two reactants in it. R R R Note: O + N R" N R" N CH R' R' R' 3 CH3 - O O O acetyl group amide The amide N is usually not nucleophilic acetamide because of a significant contribution of this resonance form. Reaction mechanism: δ- H H3C H H H3C δ+ O H N O H O N O CH3 O O N + O O H CH3 O CH3 CH3 pKa ~ -5 3 O CH3 tetrahedral (sp ) intermediate B (including ) O H N CH3 O acetanilide Chem 216 S11 Notes - Dr. Masato Koreeda Date: May 3, 2011 Topic: __Experiment 1____ page 2 of 2. Additional comments on the reaction mechanism: 1.