Calibrating Official War Art and the War on Terror

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Australian Army Journal Is Published by Authority of the Chief of Army

Australian Army Autumn edition 2019 Journal Volume XV, Number 1 Australian Army Journal Autumn edition 2019 Volume XV, Number 1 The Australian Army Journal is published by authority of the Chief of Army. The Australian Army Journal is sponsored by Head Land Capability. © Commonwealth of Australia 2019. This journal is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of study, research, criticism or review (as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968), and with standard source credit included, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Contributors are urged to ensure the accuracy of the information contained in their articles; the Editorial Advisory Board accepts no responsibility for errors of fact. Permission to reprint Australian Army Journal articles will generally be given by the Managing Editor after consultation with the author(s). Any reproduced articles must bear an acknowledgement of source. The views expressed in the Australian Army Journal are the contributors’ and not necessarily those of the Australian Army or the Department of Defence. The Commonwealth of Australia will not be legally responsible in contract, tort or otherwise for any statement made in this journal. ISSN: 1448-2843 Website: army.gov.au/our-future/aarc Twitter: @flwaustralia The Australian Army Journal Staff Editorial Director: COL Peter Connolly DSC, CSC Managing Editor: Major Cate Carter Editorial Advisory Board MAJGEN Craig Orme (Ret’d) AM, CSC, DSC Prof Genevieve Bell Prof John Blaxland Prof Peter Dean Dr Lyndal Thompson -

Annual Report 2011–12 Annual Report 2011–12 the National Gallery of Australia Is a Commonwealth (Cover) Authority Established Under the National Gallery Act 1975

ANNUAL REPORT 2011–12 ANNUAL REPORT 2011–12 The National Gallery of Australia is a Commonwealth (cover) authority established under the National Gallery Act 1975. Henri Matisse Oceania, the sea (Océanie, la mer) 1946 The vision of the National Gallery of Australia is the screenprint on linen cultural enrichment of all Australians through access 172 x 385.4 cm to their national art gallery, the quality of the national National Gallery of Australia, Canberra collection, the exceptional displays, exhibitions and gift of Tim Fairfax AM, 2012 programs, and the professionalism of our staff. The Gallery’s governing body, the Council of the National Gallery of Australia, has expertise in arts administration, corporate governance, administration and financial and business management. In 2011–12, the National Gallery of Australia received an appropriation from the Australian Government totalling $48.828 million (including an equity injection of $16.219 million for development of the national collection), raised $13.811 million, and employed 250 full-time equivalent staff. © National Gallery of Australia 2012 ISSN 1323 5192 All rights reserved. No part of this publication can be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Produced by the Publishing Department of the National Gallery of Australia Edited by Eric Meredith Designed by Susannah Luddy Printed by New Millennium National Gallery of Australia GPO Box 1150 Canberra ACT 2601 nga.gov.au/AboutUs/Reports 30 September 2012 The Hon Simon Crean MP Minister for the Arts Parliament House CANBERRA ACT 2600 Dear Minister On behalf of the Council of the National Gallery of Australia, I have pleasure in submitting to you, for presentation to each House of Parliament, the National Gallery of Australia’s Annual Report covering the period 1 July 2011 to 30 June 2012. -

Annual Report 2014–15

Annual Report 2014–15 Annual Report 2014–15 Published by the National Gallery of Australia Parkes Place, Canberra ACT 2600 GPO Box 1150, Canberra ACT 2601 nga.gov.au/aboutus/reports ISSN 1323 5192 © National Gallery of Australia 2015 All rights reserved. No part of this publication can be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Prepared by the Governance and Reporting Department Edited by Eric Meredith Designed by Carla Da Silva Pastrello Figures by Michael Tonna Index by Sherrey Quinn Printed by Union Offset Printers Cover: The 2015 Summer Art Scholars with Senior Curator Franchesca Cubillo in the Indigenous Urban gallery, 14 January 2015. 16 October 2015 Senator the Hon Mitch Fifield Minister for Communications Minister for the Arts Minister Assisting the Prime Minister for Digital Government Parliament House CANBERRA ACT 2600 Dear Minister On behalf of the Council of the National Gallery of Australia, I have pleasure in submitting to you, for presentation to each House of Parliament, the National Gallery of Australia’s annual report covering the period 1 July 2014 to 30 June 2015. This report is submitted to you as required by section 39 of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013. It is consistent with the requirements set out in the Commonwealth Authorities (Annual Reporting) Orders 2011, and due consideration has been given to the Requirements for Annual Reports approved by the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit under subsections 63(2) and 70(2) of the Public Service Act 1999 and made available by the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet on 25 June 2015. -

Biographie Peter Churcher

Galerie Thomas Fuchs GmbH & Co. KG Peter Churcher Biographie 1964 geboren in Brisbane, AU 1992 Bachelor of Fine Arts am Victorian College ( heute Deacon University ), Melbourne, AU Peter Churcher lebt und arbeitet in Barcelona, ES Einzelausstellungen ( Auswahl ) 2018 "Water falling", Philip Bacon Galleries, Brisbane, AU 2017 "Peter Churcher", Olsen, Sydney, AU 2015 Philip Bacon Galleries, Brisbane, AU 2014 "Recent PainWngs", Australian Galleries, Melbourne, AU 2012 Philip Bacon Galleries, Brisbane, AU 2011 "Recent PainWngs", Australian Galleries, Sydney, AU 2010 "Recent PainWngs", Australian Galleries, Melbourne, AU 2009 Philip Bacon Galleries, Brisbane, AU 2008 "21 months in Barcelona", Australian Galleries, Melbourne, AU 2007 "PainWngs from Barcelona", Phillip Bacon Galleries, Brisbane, AU Galerie Thomas Fuchs GmbH & Co. KG ( Amtsgericht Stugart HRA 735442 ) Reinsburgstr. 68A I 70178 Stugart I Germany Tel.: +49 711 93342415 I Mail: [email protected] I Web: www.galeriefuchs.de vertreten durch Galerie Thomas Fuchs Verwaltungs-GmbH ( Amtsgericht Stugart HRB 768563 ) Geschäasführer: Thomas Fuchs, Andreas Pucher Galerie Thomas Fuchs GmbH & Co. KG 2006 "The hunt, sacrifices and other rituals", Australian Galleries, PainWng & Sculpture, Melbourne, AU "The hunt, sacrifices and other rituals", Australian Galleries, Melbourne Art Fair, Royal ExhibiWon Building, Melbourne, AU 2005 Philip Bacon Galleries, Brisbane, AU 2004 "Recent PainWngs", Lauraine Diggins Fine Art, Melbourne, AU 2003 "Recent PainWngs", Australian Galleries, Sydney, AU 2002 "Recent works including painWngs from the Persian Gulf", Philip Bacon Galleries, Brisbane, AU 2001 Lauraine Diggins Fine Art, Melbourne, AU 2000 "Recent PainWngs", Australian Galleries, Sydney, AU 1999 Lauraine Diggins Fine Art, Melbourne, AU 1998 Philip Bacon Galleries, Brisbane, AU 1996 Lauraine Diggins Fine Art, Melbourne, AU 1994 Lauraine Diggins Fine Art, Melbourne, AU Gruppenausstellung ( Auswahl ) 2020 "WasserLust — Badende in der Kunst", Schloss Wilhelmshöhe, Museumslandschaa Hessen Kassel, DE 2019 "Male. -

Australian War Memorial Annual Report 2006–2007 Australian War Memorial Annual Report 2006–2007

AUSTRALIAN WAR MEMORIAL ANNUAL REPORT 2006–2007 AUSTRALIAN WAR MEMORIAL ANNUAL REPORT 2006–2007 The Hon. John Howard MP, Prime Minister of Australia, in the Courtyard Gallery on Remembrance Day. Annual report for the year ended 30 June 2007, together with the financial statements and the report of the Auditor-General. Images produced courtesy of the Australian War Memorial, Canberra Cover: Children in the Vietnam environment in the Discovery Zone Child using the radar in the Cold War environment in the Discovery Zone Air show during the Australian War Memorial Open Day Firing demonstration during Australian War Memorial Open Day Children in the Vietnam environment in the Discovery Zone Big Things on Display, part of the Salute to Vietnam Veterans Weekend Back cover: Will Longstaff, Menin Gate at midnight,1927 (AWM ART09807) Stella Bowen, Bomber crew 1944 (AWM ART26265) Australian War Memorial Parade Ground William Dargie, Group of VADs, 1942 (AWM ART22349) Wallace Anderson and Louis McCubbin, Lone Pine, diorama, 1924–27 (AWM ART41017) Copyright © Australian War Memorial 2007 ISSN 1441 4198 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced, copied, scanned, stored in a retrieval system, recorded, or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher. Australian War Memorial GPO Box 345 Canberra, ACT 2601 Australia www.awm.gov.au iii AUSTRALIAN WAR MEMORIAL ANNUAL REPORT 2006–2007 iv AUSTRALIAN WAR MEMORIAL ANNUAL REPORT 2006–2007 INTRODUCTION TO THE REPORT The Annual Report of the Australian War Memorial for the year ended 30 June 2007 follows the format for an Annual Report for a Commonwealth Authority in accordance with the Commonwealth Authorities and Companies (CAC) (Report of Operations) Orders 2005 under the CAC Act 1997. -

OLSEN Letterhead

PETER CHURCHER SELECTED BIOGRAPHICAL DETAILS 1964 Born 28 February, Brisbane, Australia 2006 Moved to Barcelona, Spain SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2014 ‘Recent Paintings’, Australian Galleries, Derby Street, Melbourne 2011 ‘Recent Paintings’, Australian Galleries, Roylston Street, Sydney 2010 ‘Recent Paintings’, Australian Galleries, Derby Street, Melbourne 2009 Philip Bacon Galleries, Brisbane 2008 ‘21 months in Barcelona’, Australian Galleries, Derby Street, Melbourne 2007 ‘Paintings from Barcelona’, Phillip Bacon Galleries, Brisbane 2006 ‘The hunt, sacrifices and other rituals’, Australian Galleries Painting & Sculpture, Melbourne ‘The hunt, sacrifices and other rituals’, Australian Galleries, Melbourne Art Fair, Royal Exhibition Building, Melbourne 2005 Philip Bacon Galleries, Brisbane 2004 ‘Recent Paintings’, Lauraine Diggins Fine Art, Melbourne 2003 ‘Recent Paintings’, Australian Galleries, Sydney 2002 ‘Recent works including paintings from the Persian Gulf’, Philip Bacon Galleries, Brisbane 2001 Lauraine Diggins Fine Art, Melbourne 2000 Recent Paintings’, Australian Galleries, Sydney 1999 Lauraine Diggins Fine Art, Melbourne 1998 Philip Bacon Galleries, Brisbane 1996 Lauraine Diggins Fine Art, Melbourne 1994 Lauraine Diggins Fine Art, Melbourne SELECTED GROUP EXHIBITIONS 2016 ‘Conjuring, Alchemy and Allure’, Australian Galleries, Melbourne 2015 ‘An exhibition of paintings, sculpture & works on paper’, Australian Galleries, Roylston Street, Sydney Archibald Prize, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney 2014 Doug Moran National Portrait Prize, -

Dialogues with Artists

Abstracts Dialogues with Artists 12th AICCM Paintings SIG Symposium Adelaide 21- 22 October 2010 Dialogues with Artists Abstracts of papers presented at the 12th AICCM Paintings Group Symposium Adelaide, Australia 21-22 October 2010 An initiative of the Paintings Special Interest Group of the Australian Institute for the Conservation of Cultural Material Inc., in association with the ARC-funded Twentieth Century in Paint project. Dialogues with Artists Copyright © The Australian Institute for the Conservation of Cultural Material Inc. 2010 Edited by Helen Weidenhofer Published by The Australian Institute for the Conservation of Cultural Material, Inc. AICCM GPO Box 1638 Canberra ACT 2601 Disclaimer: These abstracts have not been refereed. The opinions expressed are those of the respective author/s and not necessarily those of the AICCM. Responsibility for the content and opinions expressed, and the methods and materials used, rests solely with the author/s. Please contact the respective author/s directly if you wish to further explore any issues. No part of this publication may be reprinted in any form or by any means without prior permission of the publisher. 2 October 2010 Dialogues with Artists Contents Sponsors 4 Introduction 5 Program 6 The Twentieth Century in Paint Assoc Prof Robyn Sloggett 9 House Paints 1900-1960: History and Use Dr Harriet A L Standeven 10 The role of zinc oxide in deterioration of modern oil based paintings Gillian Osmond, J Drennan and M Monteiro 11 When Art met Science Melina Glasson, Prof Carl Schiesser, Prof Robyn Sloggett, Dr Nicole Tse and Dr Stephen Best 12 Early experiments in the use of the Australian Synchrotron for the study of paintings David Thurrowgood 13 Hidden worlds: An Infrared Survey of the Art Gallery of Western Australia’s Collection Dr M E Kubik 14 Insights into Artists’ Materials and Techniques in the Australian War Memorial Collection Alana Treasure and David Keany 16 ‘Less slick and not so clever’ - Interpreting the works of E. -

2013-01-Churcher210x21028.Pdf

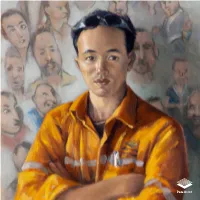

cover: 13. Xay, the local artist, Phu Kham 2012 oil on canvas 61 x 46 cm (detail) Published in association with the exhibition Our People, Community and Landscape: an exhibition of paintings from PanAust’s operations in Laos by Peter Churcher PanAust Limited Level 1, 15 James Street Fortitude Valley, Brisbane, Qld Australia 4006 www.panaust.com.au in conjunction with Philip Bacon Galleries 2 Arthur Street Fortitude Valley, Brisbane, Qld Australia 4006 www.philipbacongalleries.com.au All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publishers. Printed by Printcraft, Australia Design by Les Robinson Typeset in Linotype Frutiger Text copyright: © The authors All photographs reproduced by permission All paintings reproduced by permission © Peter Churcher O u r p e Op l e , c O m m u n it y a n d l a n d s c a p e an exhibition of paintings from panaust’s operations in laos by peter churcher 23. Young man sitting in his shop, Ban Nam Mo 2012 oil on canvas 35 x 27 cm 2 introduction ms lynda Worthaisong australian ambassador to laos i would like to congratulate Gary stafford and panaust in southeast asia. as one of the first companies to for commissioning this stunning collection of paintings develop a major mine in the country, panaust has of laos by the well-known australian artist peter also played an important role in developing today’s churcher. -

Peter Churcher Cv

PETER CHURCHER CV SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2016 Michael Reid Galleries, Berlin 2015 Philip Bacon Galleries, Brisbane 2014 Australian Galleries, Melbourne 2012 Philip Bacon Galleries, Brisbane 2011 Australian Galleries, Sydney 2010 Australian Galleries, Melbourne 2009 Philip Bacon Galleries, Brisbane 2008 Australian Galleries, Melbourne 2007 Philip Bacon Galleries, Brisbane 2006 sacrifices and other rituals’, Melbourne Art Fair, Australian Galleries, Melbourne 2005 Philip Bacon Galleries, Brisbane 2004 Lauraine Diggins Fine Art, Melbourne 2003 Australian Galleries, Sydney 2002 Philip Bacon Galleries, Brisbane 2001 Lauraine Diggins Fine Art, Melbourne 2000 Australian Galleries, Sydney 1999 Lauraine Diggins Fine Art, Melbourne 1998 Philip Bacon Galleries, Brisbane 1996 Lauraine Diggins Fine Art, Melbourne 1994 Lauraine Diggins Fine Art, Melbourne SELECTED GROUP EXHIBITIONS 2015 Archibald Finalists Exhibition, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney 2014 Archibald Finalists exhibition, AGNSW, Sydney Doug Moran National Portrait Prize, Sydney 2011 Realisme ’11, Mokum Galleries, Amsterdam 2010 PAN Art Fair, Mokum Galleries, Amsterdam 2009 Realisme 09, Mokum Galleries, Amsrerdam 2008 ‘La Collectiva, 2008’ - Pintura. Circulo de Sant Lluc, Barcelona 2007 ‘Small Pleasures’, Australian Galleries, Melbourne ‘A Selection of Portraits’ Australian Galleries, Melbourne ‘Stock Show’ Australian Galleries, Melbourne PETER CHURCHER CV 2006 ‘Stock Show’, Australian Galleries, Melbourne Finalist, ‘Kilgour Figurative Painting Prize’, Newcastle Region Art Gallery, -

Peter Churcher

PETER CHURCHER SELECTED BIOGRAPHICAL DETAILS 1964 Born 28 February, Brisbane, Australia 2006 Moved to Barcelona, Spain SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2019 ‘Through the Screen’, Australian Galleries, Melbourne ‘Through the Screen’, Michael Reid Berlin, Berlin, Germany ‘The Male Figure’, Galerie Fuchs, Stuttgart, Germany 2018 ‘Water falling’, Philip Bacon Galleries, Brisbane 2017 Olsen, Sydney ‘Rear Balcony’, Michael Reid Berlin, Berlin, Germany 2016 ‘Peter Churcher: Recent Work’, Michael Reid Berlin, Berlin, Germany 2014 ‘Recent Paintings’, Australian Galleries, Derby Street, Melbourne 2011 ‘Recent Paintings’, Australian Galleries, Roylston Street, Sydney 2010 ‘Recent Paintings’, Australian Galleries, Derby Street, Melbourne 2009 Philip Bacon Galleries, Brisbane 2008 ‘21 months in Barcelona’, Australian Galleries, Derby Street, Melbourne 2007 ‘Paintings from Barcelona’, Phillip Bacon Galleries, Brisbane 2006 ‘The hunt, sacrifices and other rituals’, Australian Galleries Painting & Sculpture, Melbourne ‘The hunt, sacrifices and other rituals’, Australian Galleries, Melbourne Art Fair, Royal Exhibition Building, Melbourne 2005 Philip Bacon Galleries, Brisbane 2004 ‘Recent Paintings’, Lauraine Diggins Fine Art, Melbourne 2003 ‘Recent Paintings’, Australian Galleries, Sydney 2002 ‘Recent works including paintings from the Persian Gulf’, Philip Bacon Galleries, Brisbane 2001 Lauraine Diggins Fine Art, Melbourne 2000 Recent Paintings’, Australian Galleries, Sydney 1999 Lauraine Diggins Fine Art, Melbourne 1998 Philip Bacon Galleries, Brisbane 1996 Lauraine -

World War II Prisoner of War Visual Art : Investigating Its Significance in Contemporary Society

Edith Cowan University Research Online Theses : Honours Theses 2009 World War II prisoner of war visual art : Investigating its significance in contemporary society Eileen Whitehead Edith Cowan University Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons Part of the Art and Design Commons, and the Cultural History Commons Recommended Citation Whitehead, E. (2009). World War II prisoner of war visual art : Investigating its significance in contemporary society. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons/1259 This Thesis is posted at Research Online. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons/1259 Edith Cowan University Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorize you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. Where the reproduction of such material is done without attribution of authorship, with false attribution of authorship or the authorship is treated in a derogatory manner, this may be a breach of the author’s moral rights contained in Part IX of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). Courts have the power to impose a wide range of civil and criminal sanctions for infringement of copyright, infringement of moral rights and other offences under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. -

Annual Report

ANNUAL REPORT of the ART GALLERY OF SOUTH AUSTRALIA for the year 1 July 2002–30 June 2003 The Hon. Mike Rann MP, Minister for the Arts Sir, I have the honour to present the sixty-second Annual Report of the Art Gallery Board of South Australia for the Gallery’s 122nd year, ended 30 June 2003. Michael Abbott QC, Chairman Art Gallery Board 2002–2003 Chairman Michael Abbott QC Members Mr Max Carter AO Mrs Susan Cocks Mr David McKee Mrs Candy Bennett Mr Richard Cohen Ms Virginia Hickey Mrs Sue Tweddell Mr Adam Wynn 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Principal Objectives 5 Major Achievements 2002-2003 6 Issues and Trends 9 Major Objectives 2003–2004 11 Resources and Administration 13 Collections 21 3 APPENDICES Appendix A Charter and Goals of the Art Gallery of South Australia 26 Appendix B1 Art Gallery Board 28 Appendix B2 Members of the Art Gallery of South Australia 28 Foundation Council and Friends of the Art Gallery of South Australia Committee Appendix B3 Art Gallery Organisational Chart 29 Appendix B4 Art Gallery Staff and Volunteers 30 Appendix C Staff Public Commitments 34 Appendix D Conservation 37 Appendix E Donors, Funds, Sponsorships 38 Appendix F Acquisitions 39 Appendix G Inward Loans 51 Appendix H Outward Loans 54 Appendix I Exhibitions and Public Programs 56 Appendix J Schools Support Services 62 Appendix K Gallery Guide Tour Services 62 Appendix L Gallery Publications 63 Appendix M Annual Attendances 65 Information Statement 66 Appendix N Financial Statements 67 4 PRINCIPAL OBJECTIVES The Art Gallery of South Australia’s objectives and functions are effectively prescribed by the Art Gallery Act, 1939 and can be described as follows: • To collect heritage and contemporary works of art of aesthetic excellence and art historical or regional significance.