Eastern State Penitentiary HSR: I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Philadelphia in Philadelphia, Your STEM Students Can Explore a City Filled with Robotics, Fossils, Butterflies, VR Experiences, Flight Simulators, and So Much More

TOP STEM DESTINATIONS: Philadelphia In Philadelphia, your STEM students can explore a city filled with robotics, fossils, butterflies, VR experiences, flight simulators, and so much more. If your students are ready to become detectives and examining skeletal remains, explore the “heart” of the Franklin Institute, or take lessons have been developed to meet Educational Standards, including Pennsylvania State Standards and the Next Generation Science Standards, Educational Destinations can make your Philadelphia history trip rewarding and memorable. EDUCATIONAL STEM OPPORTUNITIES: • Meet Pennsylvania Academic Standards • Discovery Camps • Interactive School Tours • Museum Sleepovers • Be a Forensic Anthropologist • Philadelphia Science Festival (Spring) • Scavenger Hunts • Live Science Shows • Animal Encounters • Tech Studios • Amazing Adaptations • Robotics Workshops • Escape Rooms • Movie-Making Workshops • Virtual Reality Experiences • Drone Workshops • Flight Simulators • Game Design Workshops • Planetarium Exhibits • Lego Robotics • Survivial Experiences • Engineering for Kids STEM ATTRACTIONS: • University of Pennsylvania • Garden State Discovery Museum • Penn Museum • Greener Partners’ Longview Farm • The Franklin Institute • Independence Seaport Museum • Mütter Museum at The College of Physicians of Philadelphia • John Heinz National Wildlife Refuge at Tinicum • Pennsylvania Hospital Physic Garden • John James Audubon Center at Mill Grove • Philadelphia Insectarium and Butterfly Pavilion • Linvilla Orchards • Academy of Natural Sciences -

Appendix A: Review of Existing Pedestrian and Bicycle Planning Studies

APPENDIX A: REVIEW OF EXISTING PEDESTRIAN AND BICYCLE PLANNING STUDIES This appendix provides an overview of previous planning efforts undertaken in and around Philadelphia that are relevant to the Plan. These include city initiatives, plans, studies, internal memos, and other relevant documents. This appendix briefly summarizes each previous plan or study, discusses its relevance to pedestrian and bicycle planning in Philadelphia, and lists specific recommendations when applicable. CITY OF PHILADELPHIA PEDESTRIAN & BICYCLE PLAN APRIL 2012 CONTENTS WALKING REPORTS AND STUDIES .......................................................................................................................... 1 Walking in Philadelphia ............................................................................................................................................ 1 South of South Walkabilty Plan................................................................................................................................. 1 North Broad Street Pedestrian Crash Study .............................................................................................................. 2 North Broad Street Pedestrian Safety Audit ............................................................................................................. 3 Pedestrian Safety and Mobility: Status and Initiatives ............................................................................................ 3 Neighborhood/Area Plans and Studies ................................................................................................................. -

Philadelphia and the Southern Elite: Class, Kinship, and Culture in Antebellum America

PHILADELPHIA AND THE SOUTHERN ELITE: CLASS, KINSHIP, AND CULTURE IN ANTEBELLUM AMERICA BY DANIEL KILBRIDE A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 1997 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS In seeing this dissertation to completion I have accumulated a host of debts and obligation it is now my privilege to acknowledge. In Philadelphia I must thank the staff of the American Philosophical Society library for patiently walking out box after box of Society archives and miscellaneous manuscripts. In particular I must thank Beth Carroll- Horrocks and Rita Dockery in the manuscript room. Roy Goodman in the Library’s reference room provided invaluable assistance in tracking down secondary material and biographical information. Roy is also a matchless authority on college football nicknames. From the Society’s historian, Whitfield Bell, Jr., I received encouragement, suggestions, and great leads. At the Library Company of Philadelphia, Jim Green and Phil Lapansky deserve special thanks for the suggestions and support. Most of the research for this study took place in southern archives where the region’s traditions of hospitality still live on. The staff of the Mississippi Department of Archives and History provided cheerful assistance in my first stages of manuscript research. The staffs of the Filson Club Historical Library in Louisville and the Special Collections room at the Medical College of Virginia in Richmond were also accommodating. Special thanks go out to the men and women at the three repositories at which the bulk of my research was conducted: the Special Collections Library at Duke University, the Southern Historical Collection of the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and the Virginia Historical Society. -

Art Collections FP.2012.005 Finding Aid Prepared by Caity Tingo

Art Collections FP.2012.005 Finding aid prepared by Caity Tingo This finding aid was produced using the Archivists' Toolkit October 01, 2012 Describing Archives: A Content Standard Fairmount Archives 10/1/2012 Art Collections FP.2012.005 Table of Contents Summary Information ................................................................................................................................. 3 Scope and Contents note............................................................................................................................... 4 Administrative Information .........................................................................................................................4 Collection Inventory...................................................................................................................................... 5 Lithographs, Etchings, and Engravings...................................................................................................5 Pennsylvania Art Project - Work Progress Administration (WPA)......................................................14 Watercolor Prints................................................................................................................................... 15 Ink Transparencies.................................................................................................................................17 Calendars................................................................................................................................................24 -

Philadelphia Merchants, Trans-Atlantic Smuggling, and The

Friends in Low Places: Philadelphia Merchants, Trans-Atlantic Smuggling, and the Secret Deals that Saved the American Revolution By Tynan McMullen University of Colorado Boulder History Honors Thesis Defended 3 April 2020 Thesis Advisor Dr. Virginia Anderson, Department of History Defense Committee Dr. Miriam Kadia, Department of History Capt. Justin Colgrove, Department of Naval Science, USMC 1 Introduction Soldiers love to talk. From privates to generals, each soldier has an opinion, a fact, a story they cannot help themselves from telling. In the modern day, we see this in the form of leaked reports to newspapers and controversial interviews on major networks. On 25 May 1775, as the British American colonies braced themselves for war, an “Officer of distinguished Rank” was running his mouth in the Boston Weekly News-Letter. Boasting about the colonial army’s success during the capture of Fort Ticonderoga two weeks prior, this anonymous officer let details slip about a far more concerning issue. The officer remarked that British troops in Boston were preparing to march out to “give us battle” at Cambridge, but despite their need for ammunition “no Powder is to be found there at present” to supply the Massachusetts militia.1 This statement was not hyperbole. When George Washington took over the Continental Army on 15 June, three weeks later, he was shocked at the complete lack of munitions available to his troops. Two days after that, New England militiamen lost the battle of Bunker Hill in agonizing fashion, repelling a superior British force twice only to be forced back on the third assault. -

4. FAIRMOUNT (EAST/WEST) PARK MASTER PLAN Fairmount Park System Natural Lands Restoration Master Plan Skyline of the City of Philadelphia As Seen from George’S Hill

4. FAIRMOUNT (EAST/WEST) PARK MASTER PLAN Fairmount Park System Natural Lands Restoration Master Plan Skyline of the City of Philadelphia as seen from George’s Hill. 4.A. T ASKS A SSOCIATED W ITH R ESTORATION A CTIVITIES 4.A.1. Introduction The project to prepare a natural lands restoration master plan for Fairmount (East/West) Park began in October 1997. Numerous site visits were conducted in Fairmount (East/West) Park with the Fairmount Park Commission (FPC) District #1 Manager and staff, community members, Natural Lands Restoration and Environmental Education Program (NLREEP) staff and Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia (ANSP) staff. Informal meetings at the Park’s district office were held to solicit information and opinions from district staff. Additionally, ANSP participated in the NLREEP Technical Advisory Committee (TAC) meetings in March and October 1998. These meetings were used to solicit ideas and develop contacts with other environmental scientists and land managers. A meeting was also held with ANSP, NLREEP and FPC engineering staff to discuss completed and planned projects in or affecting natural lands in Fairmount (East/West) Park. A variety of informal contacts, such as speaking at meetings of Friends groups and other clubs, and discussions during field visits provided additional input. ANSP, NLREEP and the Philadelphia Water Department (PWD) set up a program of quarterly meetings to discuss various issues of joint interest. These meetings are valuable in obtaining information useful in planning restoration and in developing concepts for cooperative programs. As a result of these meetings, PWD staff reviewed the list of priority stream restoration sites proposed for Fairmount (East/West) Park. -

ID Key Words Folder Name Cabinet 21 American Revolution, Historic

ID key words folder name cabinet 21 american revolution, historic gleanings, jacob reed, virginia dare, papers by Minnie Stewart Just 1 fredriksburg, epaulettes francis hopkins, burnes rose, buchannan, keasbey and mattison, boro council, tennis club, athletic club 22 clifton house, acession notes, ambler gazette, firefighting, east-end papers by Minnie Stewart Just 1 republcan, mary hough, history 23 faust tannery, historical society of montgomery county, Yerkes, Hovenden, ambler borough 1 clockmakers, conrad, ambler family, houpt, first presbyterian church, robbery, ordinance, McNulty, Mauchly, watershed 24 mattison, atkinson, directory, deeds 602 bethlehem pike, fire company, ambler borough 1 butler ave, downs-amey, william harmer will, mount pleasant baptist, St. Anthony fire, newt howard, ambler borough charter 25 colonial estates, hart tract, fchoolorest ave, talese, sheeleigh, opera house, ambler borough 1 golden jubilee, high s 26 mattison, asbestos, Newton Howard, Lindenwold, theatre, ambler theater, ambler/ambler borough 1 Dr. Reed, Mrs. Arthur Iliff, flute and drum, Duryea, St. Marys, conestoga, 1913 map, post office mural, public school, parade 27 street plan, mellon, Ditter, letter carriers, chamber of commerce, ambler ambler/ambler borough 1 directory 1928, Wiliam Urban, fife and drum, Wissahickon Fire Company, taprooms, prohibition, shoemaker, Jago, colony club, 28 charter, post cards, fire company, bridge, depot, library, methodist, church, ambler binder 1 colony club, fife and drum, bicentennial, biddle map, ambler park -

"Drawings in the Collections of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania

"Drawings in the Collections of The Historical Society of Pennsylvania Artist Subject Medium Date Allbright Solitude (John Penn's House) Water color c. 1840 Andre, Major John Landscape Water color 1778 Barker, J. J. Hobson House, Mantua Water color 1852 (West Phila.) Barth Washington & Tarleton at Wash c. 1850 Cowpens Becker Central High School Diploma Wash c. 1850 Besson, C. A. Slate Roof House Pen sketch 1841 Birch, T. Port of Philadelphia Wash c. 1830 Birch, T. Port of Philadelphia Wash c. 1820 Birch, W. View on Neshaminy Creek Water color c. 1800 Birch, W. View on Neshaminy Creek Water color c. 1800 Birch, W. Major General Birch Water color c. 1800 Breton, W. L. Wistar's Peach Grove, 7th & Wash c. 1830 Buttonwood Breton, W. L. Shippen Residence, Wain's Water color c. 1830 Row, 2d St. Breton, W. L. House in Germantown where Water color c. 1830 Penn preached Breton, W. L. Old Swedes' Church Water color c. 1830 Breton, W. L. Slate Roof House Water color c. 1830 Breton, W. L. St. David's, Radnor Water color c. 1830 Breton, W. L. Harriton Water color c. 1830 Breton, W. L. Oxford Church Water color c. 1830 Breton, W. L. Washington's House in High Water color c. 1830 Street Breton, W. L. Merion Meeting Water color c. 1830 Breton, W. L. Pemberton House on Schuyl- Water color 1830 L-ill Kill Breton, W. L. Wilmington Meeting Water color c. 1830 Breton, W. L. Lutheran Church, 5th & Arch Wash c. 1830 Sts. Breton, W. L. Penn Treaty Monument Water color c. -

IV. Fabric Summary 282 Copyrighted Material

Eastern State Penitentiary HSR: IV. Fabric Summary 282 IV. FABRIC SUMMARY: CONSTRUCTION, ALTERATIONS, AND USES OF SPACE (for documentation, see Appendices A and B, by date, and C, by location) Jeffrey A. Cohen § A. Front Building (figs. C3.1 - C3.19) Work began in the 1823 building season, following the commencement of the perimeter walls and preceding that of the cellblocks. In August 1824 all the active stonecutters were employed cutting stones for the front building, though others were idled by a shortage of stone. Twenty-foot walls to the north were added in the 1826 season bounding the warden's yard and the keepers' yard. Construction of the center, the first three wings, the front building and the perimeter walls were largely complete when the building commissioners turned the building over to the Board of Inspectors in July 1829. The half of the building east of the gateway held the residential apartments of the warden. The west side initially had the kitchen, bakery, and other service functions in the basement, apartments for the keepers and a corner meeting room for the inspectors on the main floor, and infirmary rooms on the upper story. The latter were used at first, but in September 1831 the physician criticized their distant location and lack of effective separation, preferring that certain cells in each block be set aside for the sick. By the time Demetz and Blouet visited, about 1836, ill prisoners were separated rather than being placed in a common infirmary, and plans were afoot for a group of cells for the sick, with doors left ajar like others. -

Teiiii^ !!Ti;;:!L||^^ -STATUS ACCESSIBLE Categbry OWNERSHIP (Check One) to the PUBLIC

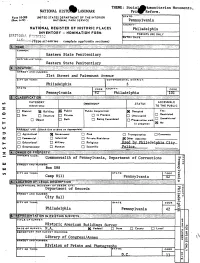

THEME: Socia Movements , NATIONAL HIST01 'LANDMARK Pri Re form. Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR STATE: (Rev. 6-72) • f NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Pennsylvania COUNTY; NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES Philadelphia INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR NPS USE ONLY {NATTOIT/J, FT5703IC' ENTRY DATE ^mWiij.nitf.'TjypQ all entries - complete applicable sections) '^^^^^^^K^y^^iy^' SitlllP W!i*:': %$$$SX ^ v;!f ';^^:-M^ '^'''^S^iii^^X^i^i^S^^^ :- • y;;£ ' ' ' . :':^:- -• * : :V COMMON: Eastern State Penitentiary AND/OR HISTORIJC: [ Eastern State Penitentiary i'**i* ^Sririiii1 :*. -: . ' ',&$;':•&. \-Stf: -: #gy&. Vii'Sviv:; .<:. :':.x:x.?:.S :•:;:..:-.:;:;.:: : . :: r :' ..:•: :1.';V.':::::::1 -?:--:i^ . ....:. :•;. ¥.:? :?:>.::;:•:•:.:¥:" .v:::::^1:;:gS::::::S*;v*ri-:':i ftyWf*,^ ;:-.;. ; .;.^:|:.:. ....;- , ••;.,.; ,: ; : '.,:• f-^..^ ;. .S:.';: >• tell^•fcf S*fV;| :*;Wfl :-K;:; • ; -f,/ •.. ••, •••<>•' • •• .;.;.•• • ;.:;••••: •••/:' ..... :.:• :'. :•:.:: ;'V •': v,-"::;.:-;.:;.: :•;•: ^V - -•;.•: ;:>:••:;. .:.'-;.,.::---7:-::i.;v ' '''-:' jji.:'./s iSgfci'S ,':':Sv:;,: ' K JftiSiSWix?-: S.^:!:?--;:. ; S*;.?. S '«:;.;Si-.--:':.-'.;"-- :':: -::x: '; ^.^-Sy .:;•?.,!.;:.•::;•" • . STREET AND NUMBER: 21st Street and Fairmount Avenue CITY OR TOWN: CONGRE SSIONAU DISTRICT: Philadelphia 3 STATE { CODE COUNTY CODE f Pennsylvania 42 Philadelpftia lol teiiii^ !!ti;;:!l||^^ -STATUS ACCESSIBLE CATEGbRY OWNERSHIP (Check One) TO THE PUBLIC C3 District (Jg Building S3 P"b''c Public Acquisition: S3 Occupied Yes: r-i n • j Q Restricted Q Site Q Structure D Private O ln Process LJ Unoccupied ' — ' D Object D Both Q Being Considere<i LJr—i Preservationo worki D*— ' Unrestricted in progress IS No 'PRESENT USE (Check One or More ea Appropriate) D Agricultural \ Q§ Government Q Park O Transportation CD Comments Q Commercial f CD Industrial Q Private Residence JS< Other (Sped*,) D Educotionalj D Military Q Religious Used bv Philadelphia C}tv D Entertainment Q Museum Q Scientific Police. -

Seventeenth Through Nineteenth Century Philadelphia Quakers As the First Advocates for Insane, Imprisoned, and Impoverishe

Seventeenth through Nineteenth scholars Hugh Barbour and J. William Frost Century Philadelphia Quakers as the note how “In the English Northwest, Fox and Nayler were at first violently beaten or stoned First Advocates for Insane, and called Puritans.”[1] Friends seeking to Imprisoned, and Impoverished escape religious intolerance in England clashed Populations with Puritan ideology in the early American colonies. The average Quaker was ostracized and persecuted in England, and more so in New Joanna Riley England. Puritans carried out harsh, cruel Senior, Secondary Education/Social Studies punishments freely in the new world, effectively stunting the spread of Quakerism in The Society of Friends, especially in the New England. As a result, Philadelphia city of Philadelphia, was the only group in the provided ample audiences who would attend seventeenth century through mid-nineteenth weekly, monthly, and annual major meetings, century to align themselves with the plight of but also to further advancement in policy and those deemed insane, imprisoned, or reform efforts. impoverished. While the connection to the Concerned with the lack of Quaker insane was seemingly decided on by those institutions for those within the Society of outside of the Society of Friends, their Friends, and excluded from English first-hand experience of being thrown into institutions, they began founding their own. prison simply for being Quaker brought to light Originally, these places were to be created by the awful conditions within. Women served not and for the Quakers themselves, in order to only as ministers and proponents within the better facilitate rehabilitation to fellow Friends. Quaker movement, but also as caregivers and Gradually, they expanded their mission to nurses within the institutions created by the include those outside the faith; Quaker or not, Friends in order to improve society as a whole. -

Washington-Rochambeau M N I B H E S a a Revolutionary Route U

N RO O C T H G A Washington-Rochambeau M N I B H E S A A Revolutionary Route U W National Historic Trail NAT AIL IONAL HISTORIC TR November-December 2014 Highlights Memorial for Revolutionary War Soldiers at Fishkill Supply Depot News Along the Trail We wish you and your loved ones a Happy Holiday Season and a great new year! Revolutionary War Cemetery in Fishkill, New York On Veteran’s Day, Nov. 11, 2014 the owner of a 10.4 acres parcel of land in Fishkill, NY held a ceremony that marked a significant step in the effort to preserve what the National Park Service (NPS) recognizes as the Revolutionary War’s single largest cemetery. The land owner placed a permanent stone marker that reads, in part, “Near here lie buried Revolutionary War heroes.” Dr. Robert Selig,a researcher studying the route of march that the Continental Army and its French Allies followed to Yorktown in 1781, identi- fied a French soldier who perished at the Fishkill Supply Depot: Jean Bonnaire, a fusilier of the Saintonge Regiment of Infantry. Per French military records, Bonnaire died in the hospital in “Phisquil” on October www.nps.gov/waro Page 1 31, 1781. This discovery raises the total number of identified soldiers to 86 and serves as a vivid reminder of France’s participation and sacrifice during our War for Independence. In late 2007, an archaeological team rediscovered the cemetery on privately-owned land just south of the Van Wyck Homestead along U.S. Route 9 some 60 miles north of New York City.