Collaborations: Creative Partnerships in Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

691 Sdc 01 Layout 1

SUE PRIDEAUX – EPOCA DE AUR SUNT DINAMITĂ! A FALSURILOR VIAȚA LUI NIETZSCHE Fake news în Epoca de Aur de Ioan T. Morar e un „Suplimentul de cultură“ volum pe care trecerea publică în avanpremieră un timpului și stilul autorului îl fragment din acest volum, fac savuros, multe dintre tradus de Bogdan-Alexandru paginile sale putând Stănescu, care va apărea în constitui material auxiliar curând la Editura Polirom. al lecțiilor de istorie sau PAGINA 12 de literatură. PAGINA 10 LA MOARTEA SCRIITORULUI SPANIOL CARLOS RUIZ ZAFÓN Acesta a decedat pe data de 19 iunie 2020 la locuința sa din Los Angeles. Cărțile sale au fost traduse în peste 40 de limbi și au numeroase premii și milioane de cititori de pe toate continentele. ANUL XVI w NR. 691 w 27 IUNIE – 3 IULIE 2020 w REALIZAT DE EDITURA POLIROM ȘI ZIARUL DE IAȘI PAGINILE 2-3 INTERVIU CU SCRIITOAREA LAVINIA BĂLULESCU „M-AM„M-AM FERITFERIT SĂSĂ FIUFIU MORALIZATOARE,MORALIZATOARE, SĂSĂ DAUDAU VERDICTE“VERDICTE“ PAGINILE 8-9 ANUL XVI NR. 691 2 actualitate 27 IUNIE – 3 IULIE 2020 www.suplimentuldecultura.ro La moartea scriitorului spaniol Carlos Ruiz Zafón Carlos Ruiz Zafón a decedat de cancer la locuinţa sa din Los Angeles. Scriitorul spaniol s-a născut la Barcelona în 1964. A lucrat în publicitate și a colaborat la reviste prestigioase, precum „La Vanguardia“ sau „El País“. A trăit câţiva ani în Los Angeles, unde a scris scenarii de film. Și-a început cariera literară în 1993 cu o carte pentru copii, Prinţul din negură (Polirom, 2011, 2015, 2017), pentru care i s-a decernat Premio Edebé. -

[email protected] Website: Nightshift.Oxfordmusic.Net Free Every Month

email: [email protected] website: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every month. NIGHTSHIFT Issue 122 September Oxford’s Music Magazine 2005 SupergrassSupergrassSupergrass on a road less travelled plus 4-Page Truck Festival Review - inside NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWNEWSS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] THE YOUNG KNIVES won You Now’, ‘Water and Wine’ and themselves a coveted slot at V ‘Gravity Flow’. In addition, the CD Festival last month after being comes with a bonus DVD which picked by Channel 4 and Virgin features a documentary following Mobile from over 1,000 new bands Mark over the past two years as he to open the festival on the Channel recorded the album, plus alternative 4 stage, alongside The Chemical versions of some tracks. Brothers, Doves, Kaiser Chiefs and The Magic Numbers. Their set was THE DOWNLOAD appears to have then broadcast by Channel 4. been given an indefinite extended Meanwhile, the band are currently in run by the BBC. The local music the studio with producer Andy Gill, show, which is broadcast on BBC recording their new single, ‘The Radio Oxford 95.2fm every Saturday THE MAGIC NUMBERS return to Oxford in November, leading an Decision’, due for release on from 6-7pm, has had a rolling impressive list of big name acts coming to town in the next few months. Transgressive in November. The monthly extension running through After their triumphant Truck Festival headline set last month, The Magic th Knives have also signed a publishing the summer, and with the positive Numbers (pictured) play at Brookes University on Tuesday 11 October. -

Central Florida Future, Vol. 27 No. 69, July 26, 1995

University of Central Florida STARS Central Florida Future University Archives 7-26-1995 Central Florida Future, Vol. 27 No. 69, July 26, 1995 Part of the Mass Communication Commons, Organizational Communication Commons, Publishing Commons, and the Social Influence and oliticalP Communication Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/centralfloridafuture University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Newsletter is brought to you for free and open access by the University Archives at STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Central Florida Future by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation "Central Florida Future, Vol. 27 No. 69, July 26, 1995" (1995). Central Florida Future. 1310. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/centralfloridafuture/1310 UCF Baseball Coach Jay Bergman named Regional coach of the year-p.B The • Flori Future Sigma Chi's Sweetheart • goes far in Competition D Melinda Miller, a in Albuquerque, New Mexico, dis playing her beauty as well as her recent UCF graduate talents on the piano. and Kappa Delta, "It was just a fabulous, week, and I was very lucky to go," placed in the top Miller said. "With over 200 chap three at the Sigma ters of Sigma Chi, it was great to Chi's International have UCF represented there." For her efforts, Melinda re Sweetheart ceived a Sigma Chi pin; she said Competition this was unusual because normally the only way to obtain one of them by JEFF HUNT is to be accepted as a pledge. News editor "That was really special," said Miller. -

Music Globally Protected Marks List (GPML) Music Brands & Music Artists

Music Globally Protected Marks List (GPML) Music Brands & Music Artists © 2012 - DotMusic Limited (.MUSIC™). All Rights Reserved. DotMusic reserves the right to modify this Document .This Document cannot be distributed, modified or reproduced in whole or in part without the prior expressed permission of DotMusic. 1 Disclaimer: This GPML Document is subject to change. Only artists exceeding 1 million units in sales of global digital and physical units are eligible for inclusion in the GPML. Brands are eligible if they are globally-recognized and have been mentioned in established music trade publications. Please provide DotMusic with evidence that such criteria is met at [email protected] if you would like your artist name of brand name to be included in the DotMusic GPML. GLOBALLY PROTECTED MARKS LIST (GPML) - MUSIC ARTISTS DOTMUSIC (.MUSIC) ? and the Mysterians 10 Years 10,000 Maniacs © 2012 - DotMusic Limited (.MUSIC™). All Rights Reserved. DotMusic reserves the right to modify this Document .This Document 10cc can not be distributed, modified or reproduced in whole or in part 12 Stones without the prior expressed permission of DotMusic. Visit 13th Floor Elevators www.music.us 1910 Fruitgum Co. 2 Unlimited Disclaimer: This GPML Document is subject to change. Only artists exceeding 1 million units in sales of global digital and physical units are eligible for inclusion in the GPML. 3 Doors Down Brands are eligible if they are globally-recognized and have been mentioned in 30 Seconds to Mars established music trade publications. Please -

Marxman Mary Jane Girls Mary Mary Carolyne Mas

Key - $ = US Number One (1959-date), ✮ UK Million Seller, ➜ Still in Top 75 at this time. A line in red 12 Dec 98 Take Me There (Blackstreet & Mya featuring Mase & Blinky Blink) 7 9 indicates a Number 1, a line in blue indicate a Top 10 hit. 10 Jul 99 Get Ready 32 4 20 Nov 04 Welcome Back/Breathe Stretch Shake 29 2 MARXMAN Total Hits : 8 Total Weeks : 45 Anglo-Irish male rap/vocal/DJ group - Stephen Brown, Hollis Byrne, Oisin Lunny and DJ K One 06 Mar 93 All About Eve 28 4 MASH American male session vocal group - John Bahler, Tom Bahler, Ian Freebairn-Smith and Ron Hicklin 01 May 93 Ship Ahoy 64 1 10 May 80 Theme From M*A*S*H (Suicide Is Painless) 1 12 Total Hits : 2 Total Weeks : 5 Total Hits : 1 Total Weeks : 12 MARY JANE GIRLS American female vocal group, protégées of Rick James, made up of Cheryl Ann Bailey, Candice Ghant, MASH! Joanne McDuffie, Yvette Marine & Kimberley Wuletich although McDuffie was the only singer who Anglo-American male/female vocal group appeared on the records 21 May 94 U Don't Have To Say U Love Me 37 2 21 May 83 Candy Man 60 4 04 Feb 95 Let's Spend The Night Together 66 1 25 Jun 83 All Night Long 13 9 Total Hits : 2 Total Weeks : 3 08 Oct 83 Boys 74 1 18 Feb 95 All Night Long (Remix) 51 1 MASON Dutch male DJ/producer Iason Chronis, born 17/1/80 Total Hits : 4 Total Weeks : 15 27 Jan 07 Perfect (Exceeder) (Mason vs Princess Superstar) 3 16 MARY MARY Total Hits : 1 Total Weeks : 16 American female vocal duo - sisters Erica (born 29/4/72) & Trecina (born 1/5/74) Atkins-Campbell 10 Jun 00 Shackles (Praise You) -

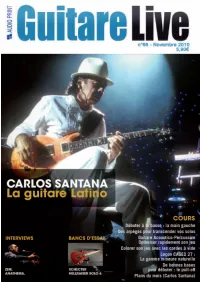

Carlos Santana

1 Sommaire Actualités 30 ESP Forest GT Arched Top Carlos Santana, 4 des classiques, des pointures mais pas d’album 31 Boss ME-25 6 Serj Tankian, Imperfect armonies 32 Ibanez Ashula SR2010 7 Anathema Amorphis 9 revisite Amorphis Le baluche vu par Les cours de 11 Phil Collins Pure Reason Revolution, 13 l’inattendu vous attend Guitare Live Spiritual Beggars, 15 rock tradition Guitare Acoustico-Percussive : Optimiser Sufjan Stevens 34 rapidement son jeu 17 entre folk et électro... Virgin Steele, Débuter à la basse : 18 contre vents et marées 37 la main gauche 20 Interpol, un avenir incertain ? 39 Des arpèges pour transcender vos solos, part.1 22 ZEM 40 Colorer son jeu avec les cordes à vide, part. 1 Banc d’essai 26 Schecter Hellraiser solo 6 43 De bonnes bases pour débuter : le pull-off 27 Schecter custom solo 6 Leçon CAGED 27: 46 La gamme mineure naturelle 28 Vigier GV Métal 29 Vigier GV Wood 48 Plans du mois (Carlos Santana) 2 Editorial www.guitare-live.com MAGAZINE Rédacteur en chef Kévin Cintas [email protected] On collaboré à ce numéro Richard Chuat Nicolas Didier-Barriac Geoffroy Lebon Manu Livertout Guitare Live Pascal Vigné Phil Elter N°66 Ruddy Meicher Novembre 2010 Aymeric Silvert Réalisation graphique Nicolas Del Castillo [email protected] Crédits photos ous en conviendrez, il est assez deux ratés ? Même dix ? Voilà donc une Couverture Christian Rose/Fastimage étrange de faire la couverture de bonne occasion de parler d’un véritable Phil Elter ce joli mois de novembre avec un Guitar Hero. -

Ritual Howls Their Body

Ritual Howls Their Body Side B (45 RPM) Side A (45 RPM) 01. Their Body 01. This Is Transcendence 02. Perfume 02. A Manifestation Of Time 03. Blood Red Moon RELEASE BIO Ritual Howls are a unique brand of industrial rock with death jangle-like guitars. Collaboratively, Ritual Howls create a surreal, introspective gloom that could fuel a disco in hell, a soundtrack to your favorite nightmares and most grisly fantasies. The trio consists of Detroit's Paul Bancell (vocals/guitars), Ben Saginaw (bass) and Chris Samuels (Synths, Samples, Drum Machines). They collect samples of the physical world and feed them with guitar, vox, bass, synth and drum machines to create an aura of darkness over a pop sensibility. Paul Bancell RELEASE INFO provides lyrics that Poe or Lovecraft would approve of while Label: felte Chris Samuels and Ben Saginaw provide sounds that bring his Catalogue Number: FLT046 macabre tales lurching into the world of the living. Format: 12” Release Date(s): September 22, 2017 The band’s Their Body EP follows up their third album, Into The UPC-LP: 616892502647 Water, released a little over a year ago on felte. Ritual Howls’ Genre: Post-Punk, Deathrock, Industrial, EBM production sees the band dipping their toes into cleaner sonic FIYL: Peter Murphy vocals, Nick Cave, Ennio Morricone, territory than previously heard. Lead single “This Is Bauhaus, a darker Calexico Transcendence,” may be their most “pop” song to date. And Territory Restrictions: None lyrically, it’s lyrics are as straightforward as we’ve heard from Box Lot: LP = 50 / CD = 30 Paul Bancell too.i “Perfume” could have the most terrifying Vinyl is Non-Returnable opening synth line that will sear your ears instantly. -

CHAPLIN, PIEZA DE MUSEO Darkness

[email protected] @Funcion_Exc EXCELSIOR LUNES 18 DE ABRIL DE 2016 NATALIE PORTMAN SE SINCERA La actriz Natalie Portman confesó que, al principio, se sintió Foto: Archivo “incómoda” con su trabajo como directora en A Tale of Love and CHAPLIN, PIEZA DE MUSEO Darkness. “Me di cuenta de que, al Ayer fue la apertura pública de Chaplin’s World (Mundo de Chaplin), ser mujer, no estaba acostumbrada en la villa suiza de Corsier-sur-Vevey, que abrió sus puertas como a expresar mis deseos de manera museo en memoria del cineasta Charles Chaplin. El sábado, cuando se tan clara tantas veces al día. cumplieron 127 años del nacimiento del comediante, sus hijos Michael Como director, tienes que ser muy y Eugene inauguraron el lugar con la presencia de invitados especiales. específico: ‘quiero esto’, ‘quiero lo “Se ha conseguido algo sólido, real, impresionante, casi desmesurado, otro’. Me sentí incómoda al principio, como la herencia aún viva de nuestro padre”, señaló Michael Chaplin >2 pero luego ¡fue muy fácil!” >4 Foto: AP Foto: PETER MURPHY DA UN GIRO A SUS ElCLÁSICOS cantante británico, quien presentará en México Stripped, explica que en este trabajo no descubrió nada nuevo de sus canciones, pero sí fue una forma diferente de acercarse a ellas >6 Es por esto que llamé a este trabajo Stripped porque de eso se trata, de desnudar las canciones hasta su punto más acústico aunque existan otros elementos.” PETER MURPHY CANTANTE Foto: Cortesía Euritmia Live SE LLAMARÁ LUNA SIMONE AGRADECE EN LAS REDES NUEVA YORK.— John Legend y Chrissy Teigen tuvieron una bebé a la que Poco después de haber ofrecido su último concierto en el Estadio bautizaron Luna Simone Stephens. -

[email protected] Website: Nightshift.Oxfordmusic.Net Free Every Month

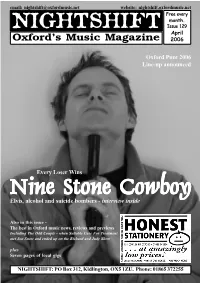

email: [email protected] website: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every month. NIGHTSHIFT Issue 129 April Oxford’s Music Magazine 2006 Oxford Punt 2006 Line-up announced Every Loser Wins NineNineNine StoneStoneStone CoCoCowbowbowboyyy Elvis, alcohol and suicide bombers - interview inside Also in this issue - The best in Oxford music news, reviews and previews Including The Odd Couple - when Suitable Case For Treatment met Jon Snow and ended up on the Richard and Judy Show plus Seven pages of local gigs NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWNEWSS Harlette Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] PUNT LINE-UP ANNOUNCED The line-up for this year’s Oxford featured a sold-out show from Fell Punt has been finalised. The Punt, City Girl. now in its ninth year, is a one-night This years line up is: showcase of the best new unsigned BORDERS: Ally Craig and bands in Oxfordshire and takes Rebecca Mosley place on Wednesday 10th May. JONGLEURS: Witches, Xmas The event features nineteen acts Lights and The Keyboard Choir. across six venues in Oxford city THE PURPLE TURTLE: Mark and post-rock is featured across showcase of new musical talent in centre, starting at 6.15pm at Crozer, Dusty Sound System and what is one of the strongest Punt the county. In the meantime there Borders bookshop in Magdalen Where I’m Calling From. line-ups ever, showing the quality are a limited number of all-venue Street before heading off to THE CITY TAVERN: Shirley, of new music coming out of Oxford Punt Passes available, priced at £7, Jongleurs, The Purple Turtle, The Sow and The Joff Winks Band. -

KUCI 88.9 FM Fall Program Guide 1990

KUCI 88.9 FM IF YOU COULD ONLY SEE WHAT YOU HEAR KUCI Program Guide A Message From The Top is a non-profit radio station licensed to the gents of the University of California, and run by KUCI is 21 ! CI students and its affiliates. KUCI broadcasts at a Since KUCI's first broadcast in 1969, our staff of 88.9 Megahertz. Our transmitter is has grown from about a half a dozen people to over 100, ocated high atop the physical sciences building on our record library to more than 30,000 and an applicatg beautiful UCI campus. All donations to the ion for a license upgrade (to increase our broadcast are tax deductible. Our Mailing address is: signal) is in the works! KUCI 88.9 FM, University of California, P.O. Box The tremendous achievements and growth of Irvine, CA, 92716-4362. Requests: (714) 856 this station has been the result of the individual efforts 824. Business: (714) 856-6868. Fax: (714) 856 and visions of a unique group- a group committed to 673. If you could see what you hear! providing new and diverse programming to UCI and its t------------------- surrounding community. But, with our maturity comes more responsibil General Manager ity. In the future, you can expect KUCI to continue pro Katie Roberts viding words and sounds that inform and entertain as Music Director well as conflict and challenge. For, on a deeper level, Todd Sievers our role as a public service station is to respect and Promotions assert the First Ammendment, which gives you the right Danielle Michaelis to choose what you hear, what you say, and what you Program Director think. -

The Music of the Goth Subculture: Postmodernism and Aesthetics Charles Allen Mueller

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2008 The Music of the Goth Subculture: Postmodernism and Aesthetics Charles Allen Mueller Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC THE MUSIC OF THE GOTH SUBCULTURE: POSTMODERNISM AND AESTHETICS By CHARLES ALLEN MUELLER A Dissertation submitted to the College of Music In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Summer Semester, 2008 Copyright 2008 Charles Mueller All Rights Reserved The members of the Committee approve the dissertation of Charles Allen Mueller defended on June 12, 2008. __________________________ Charles E. Brewer Professor Directing Dissertation __________________________ Barry Faulk Outside Committee Member __________________________ Denise Von Glahn Committee Member __________________________ Douglass Seaton Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii ACKNOLEDGEMENTS I would like to extend my most sincere gratitude to the Presser Foundation who funded my research in Great Britain. I would also like to thank journalist Mick Mercer and the staff at Rough Trade in London who provided me with important insights into the development of goth music. All of the past and present goth participants and musicians who took the time to share with me their passion for music and life experiences also -

JAMES LABRIE: New Album ‘Impermanent Resonance’ Hitting Stores Next Tuesday, August 6, 2013 in North America Via Insideoutmusic

For Immediate Release August 1, 2013 JAMES LABRIE: New Album ‘Impermanent Resonance’ Hitting Stores Next Tuesday, August 6, 2013 in North America via InsideOutMusic The world is less than one week away from witnessing the brand new solo album by Dream Theater's JAMES LABRIE, entitled Impermanent Resonance. The highly-anticipated album is out now in all other territories aside from North America, where the record will be released on August 6, 2013 via InsideOutMusic. You can pre-order the album now at this location. In addition to the standard CD and the Digital Download format, Impermanent Resonance is also available in Europe as limited edition Digipak featuring alternate artwork and two bonus tracks (‘Unraveling’ and ‘Why’) as well as on limited LP version (with the full album as bonus CD). Impermanent Resonance was once again mixed and mastered at Sweden's Fascination Street recording studios (Kreator, Opeth, Paradise Lost, etc.) with Jens Bogren and this time also Tony Lindgren, while artwork duties were handled by Gustavo Sazes / abstrata.net (Arch Enemy, Firewind, Kamelot, etc.). Want a taste? A lyric video for the anthem 'Back On The Ground' is available for listening/viewing now at this link: http://youtu.be/ralb05GOLjA. The new album's dynamic opening track, ‘Agony’, is available to be checked out as stream here: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AqOHNPdh1Pw, and downloaded here: http://www.insideoutmusic.com/specials/agony. JAMES LABRIE - Impermanent Resonance tracklisting: 1. Agony 2. Undertow 3. Slight Of Hand 4. Back On The Ground 5. I Got You 6. Holding On 7.