And the Invention of the Computer Byron Paul Mobley Iowa State University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

May 21St at the Time, the EDSAC Used IBM 726 Three Small Cathode Ray Tube Börje Langefors Screens to Display the State of Its Announced Memory

it played tic-tac-toe (known as Noughts and Crosses in the UK). May 21st At the time, the EDSAC used IBM 726 three small cathode ray tube Börje Langefors screens to display the state of its Announced memory. Each one could draw a May 21, 1952 Born: May 21, 1915; grid of 35 x 16 dots. Douglas re- purposed one of them for his Ystad, Sweden The IBM 726 was the company’s game, and obtained input (i.e. Died: Dec. 13, 2009 first magnetic tape unit, where to place a nought or intended for use with the Langefors developed the cross) via EDSAC’s rotary recently announced IBM 701 ‘infological equation’ in 1980, controller. [April 7], the company’s first which describes the difference electronic computer. between information and data in terms of additional semantic The 726 utilized half-inch tapes background and a with seven tracks. Six were for communication time interval. the data and the seventh was employed as a parity track. Langefors joined SAAB, the Some tapes were 1,200 feet long, Swedish aerospace and defense could store 2.3 MB of data, and company, in 1949 where he IBM claimed that just one could utilized analog devices for replace 12,500 punch cards. calculating wing stresses. The need for more powerful tools The drive could write 100 became evident, and the only characters per inch on a tape Swedish computer of the time, EDSAC CRT Tubes. Computer and read 75 inches per second. the BESK [April 1], was Lab, Univ. of Cambridge. CC BY To withstand the system’s fast insufficient for the task. -

The Operating System Handbook Or, Fake Your Way Through Minis and Mainframes

The Operating System Handbook or, Fake Your Way Through Minis and Mainframes by Bob DuCharme MVS Table of Contents Chapter 22 MVS: An Introduction.................................................................................... 22.1 Batch Jobs..................................................................................................................1 22.2 Interacting with MVS................................................................................................3 22.2.1 TSO.........................................................................................................................3 22.2.2 ISPF........................................................................................................................3 22.2.3 CICS........................................................................................................................4 22.2.4 Other MVS Components.........................................................................................4 22.3 History........................................................................................................................5 Chapter 23 Getting Started with MVS............................................................................... 23.1 Starting Up.................................................................................................................6 23.1.1 VTAM.....................................................................................................................6 23.1.2 Logging On.............................................................................................................6 -

Computer History – the Pitfalls of Past Futures

Research Collection Working Paper Computer history – The pitfalls of past futures Author(s): Gugerli, David; Zetti, Daniela Publication Date: 2019 Permanent Link: https://doi.org/10.3929/ethz-b-000385896 Rights / License: In Copyright - Non-Commercial Use Permitted This page was generated automatically upon download from the ETH Zurich Research Collection. For more information please consult the Terms of use. ETH Library TECHNIKGESCHICHTE DAVID GUGERLI DANIELA ZETTI COMPUTER HISTORY – THE PITFALLS OF PAST FUTURES PREPRINTS ZUR KULTURGESCHICHTE DER TECHNIK // 2019 #33 WWW.TG.ETHZ.CH © BEI DEN AUTOREN Gugerli, Zetti/Computer History Preprints zur Kulturgeschichte der Technik #33 Abstract The historicization of the computer in the second half of the 20th century can be understood as the effect of the inevitable changes in both its technological and narrative development. What interests us is how past futures and therefore history were stabilized. The development, operation, and implementation of machines and programs gave rise to a historicity of the field of computing. Whenever actors have been grouped into communities – for example, into industrial and academic developer communities – new orderings have been constructed historically. Such orderings depend on the ability to refer to archival and published documents and to develop new narratives based on them. Professional historians are particularly at home in these waters – and nevertheless can disappear into the whirlpool of digital prehistory. Toward the end of the 1980s, the first critical review of the literature on the history of computers thus offered several programmatic suggestions. It is one of the peculiar coincidences of history that the future should rear its head again just when the history of computers was flourishing as a result of massive methodological and conceptual input. -

HP 9100 a - First PC? 2 up in the Finished Spot

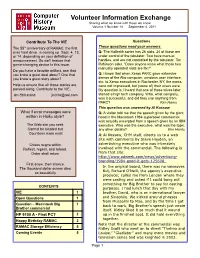

Volunteer Information Exchange Sharing what we know with those we know Volume 1 Number 14 September 4, 2011 Contribute To The VIE Questions These questions need your answers The 55 th anniversary of RAMAC, the first ever hard drive, is coming up Sept. 4, 13, Q: The Hollerith sorter has 26 slots. 24 of those are or 14, depending on your definition of under control of the tabulator. Two have manual announcement. So we'll feature that handles, and are not controlled by the tabulator. Tim game-changing device in this issue. Robinson asks, “Does anyone know what those two manually operated slots are for?” Do you have a favorite artifact, one that you know a great deal about? One that Q: I know that when Xerox PARC gave extensive you know a great story about? demos of the Alto computer, windows user interface, etc. to Xerox executives in Rochester, NY, the execs Help us ensure that all those stories are were not impressed, but (some of) their wives were. passed along. Contribute to the VIE. My question is: I heard that one of those wives later Jim Strickland [email protected] started a high tech company. Who, what company, was it successful, and did they use anything from PARC? Kim Harris This question was anwered by Al Kossow What if error messages were Q: A visitor told me that the speech given by the giant written in Haiku style? head in the Macintosh 1984 superbowl commercial was actually excerpted from a speech given by an IBM The Web site you seek executive. -

United States Securities and Exchange Commission Washington, D.C

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20549 FORM 8-K CURRENT REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15 (d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 Date of Report: April 20, 2015 (Date of earliest event reported) INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS MACHINES CORPORATION (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) New York 1-2360 13 -0871985 (State of Incorporation) (Commission File Number) (IRS employer Identification No.) ARMONK, NEW YORK 10504 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip Code) 914-499-1900 (Registrant’s telephone number) Check the appropriate box below if the Form 8-K filing is intended to simultaneously satisfy the filing obligation of the registrant under any of the following provisions: § Written communications pursuant to Rule 425 under the Securities Act (17 CFR 230.425) § Soliciting material pursuant to Rule 14a-12 under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.14a-12) § Pre-commencement communications pursuant to Rule 14d-2(b) under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.14d-2(b)) § Pre-commencement communications pursuant to Rule 13e-4(c) under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.13e-4(c)) Item 2.02. Results of Operations and Financial Condition. Attachment I of this Form 8-K contains the prepared remarks for IBM’s Chief Financial Officer Martin Schroeter’s first quarter earnings presentation to investors on April 20, 2015, as well as certain comments made by Mr. Schroeter during the question and answer period, edited for clarity. Attachment II contains Slide 23 from Mr. Schroeter’s first quarter earnings presentation corrected for mislabeled rows. Certain reconciliation and other information (“Non-GAAP Supplemental Materials”) for this presentation was included in Attachment II to the Form 8-K that IBM submitted on April 20, 2015, which included IBM’s press release dated April 20, 2015. -

An Early Program Proof by Alan Turing F

An Early Program Proof by Alan Turing F. L. MORRIS AND C. B. JONES The paper reproduces, with typographical corrections and comments, a 7 949 paper by Alan Turing that foreshadows much subsequent work in program proving. Categories and Subject Descriptors: 0.2.4 [Software Engineeringj- correctness proofs; F.3.1 [Logics and Meanings of Programs]-assertions; K.2 [History of Computing]-software General Terms: Verification Additional Key Words and Phrases: A. M. Turing Introduction The standard references for work on program proofs b) have been omitted in the commentary, and ten attribute the early statement of direction to John other identifiers are written incorrectly. It would ap- McCarthy (e.g., McCarthy 1963); the first workable pear to be worth correcting these errors and com- methods to Peter Naur (1966) and Robert Floyd menting on the proof from the viewpoint of subse- (1967); and the provision of more formal systems to quent work on program proofs. C. A. R. Hoare (1969) and Edsger Dijkstra (1976). The Turing delivered this paper in June 1949, at the early papers of some of the computing pioneers, how- inaugural conference of the EDSAC, the computer at ever, show an awareness of the need for proofs of Cambridge University built under the direction of program correctness and even present workable meth- Maurice V. Wilkes. Turing had been writing programs ods (e.g., Goldstine and von Neumann 1947; Turing for an electronic computer since the end of 1945-at 1949). first for the proposed ACE, the computer project at the The 1949 paper by Alan M. -

Turing's Influence on Programming — Book Extract from “The Dawn of Software Engineering: from Turing to Dijkstra”

Turing's Influence on Programming | Book extract from \The Dawn of Software Engineering: from Turing to Dijkstra" Edgar G. Daylight∗ Eindhoven University of Technology, The Netherlands [email protected] Abstract Turing's involvement with computer building was popularized in the 1970s and later. Most notable are the books by Brian Randell (1973), Andrew Hodges (1983), and Martin Davis (2000). A central question is whether John von Neumann was influenced by Turing's 1936 paper when he helped build the EDVAC machine, even though he never cited Turing's work. This question remains unsettled up till this day. As remarked by Charles Petzold, one standard history barely mentions Turing, while the other, written by a logician, makes Turing a key player. Contrast these observations then with the fact that Turing's 1936 paper was cited and heavily discussed in 1959 among computer programmers. In 1966, the first Turing award was given to a programmer, not a computer builder, as were several subsequent Turing awards. An historical investigation of Turing's influence on computing, presented here, shows that Turing's 1936 notion of universality became increasingly relevant among programmers during the 1950s. The central thesis of this paper states that Turing's in- fluence was felt more in programming after his death than in computer building during the 1940s. 1 Introduction Many people today are led to believe that Turing is the father of the computer, the father of our digital society, as also the following praise for Martin Davis's bestseller The Universal Computer: The Road from Leibniz to Turing1 suggests: At last, a book about the origin of the computer that goes to the heart of the story: the human struggle for logic and truth. -

Big Blue in the Bottomless Pit: the Early Years of IBM Chile

Big Blue in the Bottomless Pit: The Early Years of IBM Chile Eden Medina Indiana University In examining the history of IBM in Chile, this article asks how IBM came to dominate Chile’s computer market and, to address this question, emphasizes the importance of studying both IBM corporate strategy and Chilean national history. The article also examines how IBM reproduced its corporate culture in Latin America and used it to accommodate the region’s political and economic changes. Thomas J. Watson Jr. was skeptical when he The history of IBM has been documented first heard his father’s plan to create an from a number of perspectives. Former em- international subsidiary. ‘‘We had endless ployees, management experts, journalists, and opportunityandlittleriskintheUS,’’he historians of business, technology, and com- wrote, ‘‘while it was hard to imagine us getting puting have all made important contributions anywhere abroad. Latin America, for example to our understanding of IBM’s past.3 Some seemed like a bottomless pit.’’1 However, the works have explored company operations senior Watson had a different sense of the outside the US in detail.4 However, most of potential for profit within the world market these studies do not address company activi- and believed that one day IBM’s sales abroad ties in regions of the developing world, such as would surpass its growing domestic business. Latin America.5 Chile, a slender South Amer- In 1949, he created the IBM World Trade ican country bordered by the Pacific Ocean on Corporation to coordinate the company’s one side and the Andean cordillera on the activities outside the US and appointed his other, offers a rich site for studying IBM younger son, Arthur K. -

Object Summary Collections 11/19/2019 Collection·Contains Text·"Manuscripts"·Or Collection·Contains Text·"University"·And Status·Does Not Contain Text·"Deaccessioned"

Object_Summary_Collections 11/19/2019 Collection·Contains text·"Manuscripts"·or Collection·Contains text·"University"·and Status·Does not contain text·"Deaccessioned" Collection University Archives Artifact Collection Image (picture) Object ID 1993-002 Object Name Fan, Hand Description Fan with bamboo frame with paper fan picture of flowers and butterflies. With Chinese writing, bamboo stand is black with two legs. Collection University Archives Artifact Collection Image (picture) Object ID 1993-109.001 Object Name Plaque Description Metal plaque screwed on to wood. Plaque with screws in corner and engraved lettering. Inscription: Dr. F. K. Ramsey, Favorite professor, V. M. Class of 1952. Collection University Archives Artifact Collection Image (picture) Object ID 1993-109.002 Object Name Award Description Gold-colored, metal plaque, screwed on "walnut" wood; lettering on brown background. Inscription: Present with Christian love to Frank K. Ramsey in recognition of his leadership in the CUMC/WF resotration fund drive, June 17, 1984. Collection University Archives Artifact Collection Image (picture) Object ID 1993-109.003 Object Name Plaque Description Wood with metal plaque adhered to it; plque is silver and black, scroll with graphic design and lettering. Inscription: To Frank K. Ramsey, D. V. M. in appreciation for unerring dedication to teaching excellence and continuing support of the profession. Class of 1952. Page 1 Collection University Archives Artifact Collection Image (picture) Object ID 1993-109.004 Object Name Award Description Metal plaque screwed into wood; plaque is in scroll shape on top and bottom. Inscription: 1974; Veterinary Service Award, F. K. Ramsey, Iowa Veterinary Medical Association. Collection University Archives Artifact Collection Image (picture) Object ID 1993-109.005 Object Name Award Description Metal plaque screwed onto wood; raised metal spray of leaves on lower corner; black lettering. -

Herman Heine Goldstine

Herman Heine Goldstine Born September 13, 1913, Chicago, Ill.; Army representative to the ENIAC Project, who later worked with John von Neumann on the logical design of the JAS computer which became the prototype for many early computers-ILLIAC, JOHNNIAC, MANIAC author of The Computer from Pascal to von Neumann, one of the earliest textbooks on the history of computing. Education: BS, mathematics, University of Chicago, 1933; MS, mathematics, University of Chicago, 1934; PhD, mathematics, University of Chicago, 1936. Professional Experience: University of Chicago: research assistant, 1936-1937, instructor, 1937-1939; assistant professor, University of Michigan, 1939-1941; US Army, Ballistic Research Laboratory, Aberdeen, Md., 1941-1946; Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton University, 1946-1957; IBM: director, Mathematics Sciences Department, 1958-1965, IBM fellow, 1969. Honors and Awards: IEEE Computer Society Pioneer Award, 1980; National Medal of Science, 1985; member, Information Processing Hall of Fame, Infornart, Dallas, Texas, 1985. Herman H. Goldstine began his scientific career as a mathematician and had a life-long interest in the interaction of mathematical ideas and technology. He received his PhD in mathematics from the University of Chicago in 1936 and was an assistant professor at the University of Michigan when he entered the Army in 1941. After participating in the development of the first electronic computer (ENIAC), he left the Army in 1945, and from 1946 to 1957 he was a member of the Institute for Advanced Study (IAS), where he collaborated with John von Neumann in a series of scientific papers on subjects related to their work on the Institute computer. In 1958 he joined IBM Corporation as a member of the research planning staff. -

Economic Research Working Paper No. 27

Economic Research Working Paper No. 27 Breakthrough technologies – Semiconductor, innovation and intellectual property Thomas Hoeren Francesca Guadagno Sacha Wunsch-Vincent Economics & Statistics Series November 2015 Breakthrough Technologies – Semiconductors, Innovation and Intellectual Property Thomas Hoeren*, Francesca Guadagno**, Sacha Wunsch-Vincent** Abstract Semiconductor technology is at the origin of today’s digital economy. Its contribution to innova- tion, productivity and economic growth in the past four decades has been extensive. This paper analyzes how this breakthrough technology came about, how it diffused, and what role intellec- tual property (IP) played historically. The paper finds that the semiconductor innovation ecosys- tem evolved considerably over time, reflecting in particular the move from early-stage invention and first commercialization to mass production and diffusion. All phases relied heavily on con- tributions in fundamental science, linkages to public research and individual entrepreneurship. Government policy, in the form of demand-side and industrial policies were key. In terms of IP, patents were used intensively. However, they were often used as an effective means of sharing technology, rather than merely as a tool to block competitors. Antitrust policy helped spur key patent holders to set up liberal licensing policies. In contrast, and potentially as a cautionary tale for the future, the creation of new IP forms – the sui generis system to protect mask design - did not produce the desired outcome. Finally, copyright has gained in importance more re- cently. Keywords: semiconductors, innovation, patent, sui generis, copyright, intellectual property JEL Classification: O330, O340, O470, O380 Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the World Intellectual Property Organization or its member states. -

Golden Yearbook

Golden Yearbook Golden Yearbook Stories from graduates of the 1930s to the 1960s Foreword from the Vice-Chancellor and Principal ���������������������������������������������������������5 Message from the Chancellor ��������������������������������7 — Timeline of significant events at the University of Sydney �������������������������������������8 — The 1930s The Great Depression ������������������������������������������ 13 Graduates of the 1930s ���������������������������������������� 14 — The 1940s Australia at war ��������������������������������������������������� 21 Graduates of the 1940s ����������������������������������������22 — The 1950s Populate or perish ���������������������������������������������� 47 Graduates of the 1950s ����������������������������������������48 — The 1960s Activism and protest ������������������������������������������155 Graduates of the 1960s ���������������������������������������156 — What will tomorrow bring? ��������������������������������� 247 The University of Sydney today ���������������������������248 — Index ����������������������������������������������������������������250 Glossary ����������������������������������������������������������� 252 Produced by Marketing and Communications, the University of Sydney, December 2016. Disclaimer: The content of this publication includes edited versions of original contributions by University of Sydney alumni and relevant associated content produced by the University. The views and opinions expressed are those of the alumni contributors and do