Episode 131 PEA Arrest & Pseudopea

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ventricular Rhythms Originate Below the Branching Portion of The

Northwest Community Healthcare Paramedic Program VENTRICULAR DYSRHYTHMIAS Pacemakers Connie J. Mattera, M.S., R.N., EMT-P Reading assignments: Bledsoe Vol 3; pp. 96-109 SOPs: VT with pulse; Ventricular fibrillation/PVT; Asystole/PEA Drugs: Amiodarone, magnesium, epinephrine 1mg/10mL Procedure manual: Defibrillation; Mechanical Circulatory Support (MCS) using a Ventricular Assist Device KNOWLEDGE OBJECTIVES: Upon completion of the reading assignments, class and homework questions, reviewing the SOPs, and working with their small group, each participant will independently do the following with at least an 80% degree of accuracy and no critical errors: 1. Identify the intrinsic rates, morphology, conduction pathways, and common ECG features of ventricular beats/rhythms. 2. Identify on a 6-second strip the following: a) Idioventricular rhythm b) Accelerated idioventricular rhythm c) Ventricular tachycardia: monomorphic & polymorphic d) Ventricular escape beats e) Premature Ventricular Contractions (PVCs) f) Ventricular fibrillation g) Asystole h) Paced rhythms i) Intraventricular conduction defects (Bundle branch blocks) 3. Systematically evaluate each complex/rhythm for the following: a) Rate (atrial and ventricular) b) Rhythm: Regular/irregular - R-R Interval, P-P Interval c) Presence/absence/morphology of P waves d) Presence/absence/morphology of QRS complexes d) P-QRS relationships f) QRS duration 4. Correlate the cardiac rhythm with patient assessment findings to determine the emergency treatment for each rhythm according to NWC EMSS SOPs. 5. Discuss the action, prehospital indications, side effects, dose and contraindications of the following during VT a) Amiodarone b) Magnesium 6. Describe the indications, equipment needed, critical steps, and patient monitoring parameters for cardioversion and defibrillation. 7. Identify the management of a patient with an implanted defibrillator and/or pacemaker. -

A Simplified and Structured Teaching Tool for the Evaluation and Management of Pulseless Electrical Activity

R e v i e w Med Princ Pract 2014;23:1–6 Received: February 27, 2013 DOI: 10.1159/000354195 Accepted: July 2, 2013 Published online: August 13, 2013 A Simplified and Structured Teaching Tool for the Evaluation and Management of Pulseless Electrical Activity a b a, c L a s z l o L i t t m a n n Devin J. Bustin Michael W. Haley a b c D e p a r t m e n t s o f Internal Medicine and Emergency Medicine, and Pulmonary and Critical Care Consultants, Carolinas Medical Center, Charlotte, N.C., USA K e y W o r d s Introduction Pulseless electrical activity · Cardiopulmonary resuscitation · Electrocardiogram · Echocardiogram Patients with pulseless electrical activity (PEA) ac- count for up to 30% of cardiac arrest victims [1, 2] . The survival rate of patients with PEA is much worse than that A b s t r a c t of cardiac arrest patients with shockable rhythms [1, 3] . Cardiac arrest victims who present with pulseless electrical Studies suggest that cause-specific treatment of PEA is activity (PEA) usually have a grave prognosis. Several condi- more effective than general treatments offered by ad- tions, however, have cause-specific treatments which, if ap- vanced cardiac life support (ACLS) guidelines such as plied immediately, can lead to quick and sustained recovery. cardiac massage, epinephrine and vasopressin [4] . High- Current teaching focuses on recollection of numerous con- er-dose epinephrine has actually been shown to be associ- ditions that start with the letters H or T as potential causes of ated with worse outcomes [5] . -

SAEMS Cardiac Arrest Standing Order Self-Learning Module

SAEMS Cardiac Arrest Standing Order Self-Learning Module Robert Callan University Physicians Hospital September 8, 2009 SAEMS Standing Order Training Module Cardiac Arrest PURPOSE This SAEMS Standing Order Training Module has been developed to serve as a template for EMS provider training. The intent is to provide consistent and concise information to all providers practicing within the SAEMS Region. The content of the Training Module has been developed by the Protocol Development and Review Committee and includes the specific Standing Order, resource and reference material and instructions for completing the Training Module to obtain continuing education credit. One hour of SAEMS continuing education credit may be issued following successful completion of the module. OBJECTIVES 1. Review basic cardiac arrest evaluation techniques 2. Recognize cardiac arrest pathology 3. Apply the Cardiac Arrest Standing Order appropriately Instructions 1. Review the accompanying information, Standing Order and any additional reference material as necessary. 2. Complete the attached posttest and return it to your supervisor or base hospital coordinator. 3. A SAEMS CE Form will be issued to providers scoring greater than _____% on the posttest. 4. Please contact your Base Hospital Manager/Coordinator for questions, suggestions or concerns. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Purpose 2. Objectives 3. Instructions 4. Table of Contents 5. Cardiac Arrest 6. Glossary 7. Cardiac Arrest Center (CAC) Triage Protocol 8. Standing Order 9. Posttest 2 INTRODUCTION Cardiac Arrest Cardiac arrest, also known as cardiopulmonary arrest or circulatory arrest, is the sudden abrupt cessation of normal circulation of the blood due to failure of the heart to contract effectively during systole. -

2015 AHA BLS And

Update 2015 AHA BLS and 40 l Nursing2016 l Volume 46, Number 2 www.Nursing2016.com Copyright © 2016 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved. ACLS guidelines By Karen Jean Craig-Brangan, BS, RN, EMT-P, and Mary Patricia Day, MSN, RN, CRNA ADVANCED CARDIOVASCULAR life support (ACLS) encompasses the entire spectrum of care from basic life support (BLS) to postcardiac arrest care. The 2015 American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines include recommendations on the use of I.V./intraosseous (I.O.) epinephrine, I.V./I.O. vasopressin during cardiac arrest, and end-tidal carbon dioxide (ETCO2) measurements to predict patient outcome.1 Let’s take a closer look at these changes and more. Managing cardiac arrest in an adult The Adult Cardiac Arrest Algorithm outlines a plan of care for the patient in cardiac arrest sec- ondary to pulseless ventricular tachycardia (pVT)/ ventricular fibrillation (VF). After determining unresponsiveness, apnea, and pulselessness, the clinician administers chest compressions and ventilations at a ratio of 30:2 respectively until an advanced airway is in place. Advanced air- ways include an endotracheal tube (ETT) or supraglottic airway (SGA) device such as a laryn- geal mask airway, laryngeal tube, or esophageal obturator airway. The new BLS guidelines recommend a com- pression rate of at least 100/minute and no great- er than 120/minute, and a compression depth of at least 2 in (5 cm) and no greater than 2.4 in (6 cm) for an average adult.2 Upper limits for both compression rate and depth have been provided TOCK in the updated guidelines based on preliminary /iS data suggesting that excessive compression MAGES I rates and depths can adversely affect patient out- comes. -

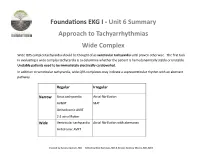

Foundations EKG I - Unit 6 Summary Approach to Tachyarrhythmias Wide Complex

Foundations EKG I - Unit 6 Summary Approach to Tachyarrhythmias Wide Complex Wide QRS complex tachycardia should be thought of as ventricular tachycardia until proven otherwise. The first task in evaluating a wide complex tachycardia is to determine whether the patient is hemodynamically stable or unstable. Unstable patients need to be immediately electrically cardioverted. In addition to ventricular tachycardia, wide QRS complexes may indicate a supraventricular rhythm with an aberrant pathway. Regular Irregular Narrow Sinus tachycardia Atrial fibrillation AVNRT MAT Orthodromic AVRT 2:1 atrial flutter Wide Ventricular tachycardia Atrial fibrillation with aberrancy Antidromic AVRT Created by Ashley Deutsch, MD Edited by Nick Hartman, MD & Kristen Grabow Moore, MD, MEd Ventricular tachycardia is likely if there is: • AV dissociation • QRS over 140s • Positive precordial QRS complexes Sustained ventricular tachycardia lasts over 30 seconds. Treatment of hemodynamically stable ventricular tachycardia may include administration of lidocaine, procainamide, or amiodarone. It is important to consider reversible causes (commonly referred to as the “Hs and Ts”). Unstable ventricular tachycardia mandates immediate synchronized cardioversion. SVT with aberrant conduction pathways may also cause wide complex tachycardia. Conduction of AVRT may be ortho- dromic (traveling down the normal direction of the nerve fibers) or antidromic (opposite to the normal conduction path- way). Antidromic conduction tends to cause a wide QRS complex whereas orthodromic often causes a narrow complex . Courtesy of Edward Burns of Life in the Fast Lane Creative Commons License Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW) is a pre-excitation syndrome. Evidence of the accessory pathway causing tachycardia can be seen in the delta wave causing upslurring to the QRS with a short PR interval. -

Denver Metropolitan Prehospital Protocols

Denver Metropolitan Prehospital Protocols These protocols are considered property of the Denver Metro EMS Medical Directors and contributors listed below. They may be utilized and edited by others as long as the Denver Metro EMS Medical Directors are credited. We also ask to be notified - DMEMSMD c/o St. Anthony EMS – 11600 W. 2nd Place Lakewood, CO 80204 Table of Contents 0001 General Guidelines: Introduction 0002 General Guidelines: Confidentiality 0003 General Guidelines: Consent 0004 General Guidelines: Physician on Scene 0005 General Guidelines: Termination of Resuscitation & field pronouncement 0006 General Guidelines: Advanced medical directives 0007 General Guidelines: Patient determination 0008 General Guidelines: Non-transport/refusal 0009 General Guidelines: Emergency Department divert and advisory Procedural Protocols 0100 Orotracheal Intubation 0110 Nasotracheal Intubation 0120 Percutaneous Cricothyrotomy 0130 King Airway 0140 Continuous Positive Airway Pressure (CPAP) 0150 Capnography 0160 Synchronized Cardioversion 0170 Transcutaneous Cardiac Pacing 0180 Therapeutic Induced Hypothermia after Cardiac Arrest 0190 Restraints 0200 Tourniquets 0210 Needle Thoracostomy for Tension Pneumonthorax Decompression 0220 Intraosseus Cathether Placement 0230 Epistaxis Management Protocols 1010 Obstructed Airway 2000 Cardiac Arrest: General Principles 2020 ALS Pulseless Arrest 2030 Tachyarrhythmia with Poor Perfusion 2040 Bradyarrhythmia with Poor Perfusion 2050 Adult Chest Pain 2051 Cardiac Alert 2100 Hypertension 3010 Universal Respiratory -

Adult Cardiac Arrest History Signs and Symptoms Differential • Events Leading to Arrest • Unresponsive • Medical Vs

Adult Cardiac Arrest History Signs and Symptoms Differential • Events leading to arrest • Unresponsive • Medical vs. Trauma • Estimated downtime • Apneic • VF vs. Pulseless VT • Past medical history • Pulseless • Asystole • Medications • PEA • Existence of terminal illness • Primary Cardiac event vs. Respiratory arrest or Drug Overdose 68 Adult Cardiac Arrest Cardiac Arrest Code Commander Checklist Post ROSC Cardiac Arrest Checklist • Code Commander is identified • Airway • Time Keeper is identified ◦ ITD has been removed, ASSESS EtCO2 (should be >20 with good waveform) • Monitor is visible and a dedicated provider is viewing the rhythm with all leads attached ◦ Evaluate for post-resuscitation airway placement (e.g. ETT) • Confirm that continuous compressions are ongoing at 100-120 ◦ Mask is available for BVM in case advanced airway fails beats per minute • Breathing • Defibrillations are occurring at 2 minute intervals for shockable ◦ Check O2 supply and SpO2 to TITRATE to 94-99% rhythms ◦ Do not try to obtain a “normal” EtCO2 by increasing • O2 cylinder with adequate oxygen is attached to BVM respiratory rate • EtCO2 waveform is present and value is being monitored ◦ Avoid hyperventilation • ITD (Res-Q-Pod) is in place • Circulation • Vascular access has been obtained (IV or IO) with IV fluids being ◦ Assign a provider to maintain FINGER on pulse during all administered patient movements • Underlying causes (including tension PTX) are considered and ◦ Continuous visualization of cardiac monitor rhythm treated early in arrest ◦ Obtain -

RESUSCITATION PROCEDURES Divided Into Appropriate Areas of Clinical Expertise, Which Illustrate Hands-On Techniques

COMPREHENSIVE ADVANCED LIFE SUPPORT CALS PROVIDER MANUAL THE FIRST 30 MINUTES EDITION 15 2019 DIRECTOR: DARRELL CARTER, MD EDUCATION MANAGER: Ann Gihl, RN Comprehensive Advanced Life Support © January 2019 All Rights Reserved www.calsprogram.org NOTE TO USERS The CALS course was developed for rural and other healthcare providers who work in an environment with limited resources, but who are also responsible for the emergency care in their often geographically isolated communities. Based on needs assessment and ongoing provider participant feedback, the CALS course endorses practical evaluation and treatment recommendations that reflect broad consensus and time-tested approaches. The organization of the CALS Provider Manual reflects the CALS Universal Approach. The FIRST THIRTY MINUTES (previously known as Volume 1) of patient care. ACUTE CARE ALGORITHMS/ TREATMENT PLANS/AND ACRONYMS provide critical care tools and are designed for quick access. The STEPS describe a system to diagnose and treat emergent patients. The FOCUSED CLINICAL PATHWAYS provide a brief review of most conditions encountered in the emergency setting. Supplement to the First Thirty Minutes (previously known as Volume 2) is composed of RESUSCITATION PROCEDURES divided into appropriate areas of clinical expertise, which illustrate hands-on techniques. Reference material for the First thirty Minutes (previously known as Volume 3) is composed of DIAGNOSIS, TREATMENT, AND TRANSITION TO DEFINITIVE CARE PORTALS, is also divided into appropriate areas of clinical expertise. In conjunction with the FOCUSED CLINICAL PATHWAYS, these detail further specialized guidelines on many conditions. Recommendations in the CALS course manual are aligned with those from organizations such as the American Heart Association, American College of Surgeons, American Academy of Family Physicians, American College of Emergency Physicians, American Academy of Neurology, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, American Academy of Pediatrics, National Institutes of Health, and Centers for Disease Control. -

Call for Help!

Air Embolism 2 Anaphylaxis 3 Anterior Mediastinal Mass 4 Bradycardia 5 Bronchospasm 6 PediCrisis Cardiac Arrest 7-9 Difficult Airway 10 Fire: Airway / OR 11-12 Hyperkalemia 13 Hypertension 14 Hypotension 15 CRITICAL EVENTS Hypoxia 16 CARDS Intracranial Pressure 17 Local Anesthetic Toxicity 18 Call for help! Loss of Evoked Potentials 19 20 Code Team ___________ Malignant Hyperthermia PICU ___________ Myocardial Ischemia 21 Fire ___________ Pulmonary Hypertension 22 Overhead STAT ___________ Tachycardia 23 ECMO ___________ Tension pneumothorax 24 Nofy surgeon. Transfusion & Reactions 25-26 Trauma 27 Revision May 31, 2017 Air Embolism ↓ EtCO2 ↓ SaO2 ↓ BP 2 § Notify Surgeon, stop nitrous oxide and volatile agents. Increase O2 to 100%. § Stop air entrainment: Find air entry point, stop source, and limit further entry. • Ask surgeon to: • Flood wound with irrigation/soaked saline dressing • Turn off all pressurized gas sources, e.g. laparoscope, endoscope • Place bone wax or cement on exposed bone edges • Check for open venous lines or air in IV tubing Embolism Air • Lower surgical site below level of heart (if possible) • Perform Valsalva on patient using hand ventilation § Consider: • Compress jugular veins intermittently if head or cranial case • Aspirate from central venous catheter § Hemodynamic support if hypotensive: • Give epinephrine 1-10 MICROgrams/kg, followed by infusion of epinephrine 0.02-1 MICROgrams/kg/min or norepinephrine 0.05-2 MICROgrams/kg/min • Chest compressions: 100/min to force air through lock, even if not in cardiac -

Optimizing Survival Outcomes for Adult Patients with Nontraumatic

October 2016 Optimizing Survival Outcomes Volume 18, Number 10 Author For Adult Patients With Julianna Jung, MD, FACEP Associate Professor and Director of Undergraduate Medical Education, Department of Emergency Medicine, Johns Hopkins University School of Nontraumatic Cardiac Arrest Medicine, Baltimore, MD Peer Reviewers Abstract William J. Brady, MD Professor of Emergency Medicine and Medicine; Chair, Medical Patient survival after cardiac arrest can be improved significantly Emergency Response Committee; Medical Director, Emergency Management, University of Virginia Medical Center, Charlottesville, VA with prompt and effective resuscitative care. This systematic Faheem Guirgis, MD, FACEP review analyzes the basic life support factors that improve survival Assistant Professor of Emergency Medicine, University of Florida Health outcome, including chest compression technique and rapid defi- Jacksonville, Department of Emergency Medicine, Division of Research, brillation of shockable rhythms. For patients who are successfully Jacksonville, FL resuscitated, comprehensive postresuscitation care is essential. Tar- CME Objectives geted temperature management is recommended for all patients Upon completion of this article, you should be able to: who remain comatose, in addition to careful monitoring of oxygen- 1. Describe the elements of high-quality basic life support. 2. Discuss the evidentiary basis and current guidelines for advanced ation, hemodynamics, and cardiac rhythm. Management of cardiac life support interventions. arrest in circumstances such as pregnancy, pulmonary embolism, 3. Describe essential considerations in postresuscitation care following opioid overdose and other toxicologic causes, hypothermia, and restoration of spontaneous circulation. coronary ischemia are also reviewed. 4. List modifications to standard resuscitation protocols that may be considered in special resuscitation situations. Prior to beginning this activity, see “Physician CME Information” on the back page. -

2.4. Cardiac Arrest

2.4 -Cardiac Arrest Prehospital Management of Cardiac Arrest HISTORY SIGNS and SYMPTOMS ASSESSMENT • Events leading to arrest • Unresponsive • Medical vs. Trauma • Estimated downtime • Apneic • V-fib vs. Pulseless V-tach • Past medical history, DNR • Pulseless • Asystole • Medications/Allergies • Pulseless Electrical Activity • Existence of terminal illness • (PEA) • Obvious signs of death • Causes (H’s and T’s) TREATMENT GUIDELINES **MEDICAL CONTROL* R-EMR E-EMT I-85 A-EMT I-99 P-PARAMEDIC Level II Intervention ***Higher levels of providers are responsible for lower level treatments*** • Initial Patient Contact • Evaluate for criteria of DOA or DNR Directive: If none, start CPR. Attach LUCAS. R • If ALS not available, proceed with Automated Defibrillator (AED) Procedure. • Implement Airway Management Procedures. Ventilate no more than 12 breaths/min • Obtain Blood Glucose Level. • Obtain and reassess vital signs every 5 minutes. • Secure airway using Blind Insertion Airway Device (BIAD) such as a King airway. • Determine patient destination and transportation mode. E • Transport to receiving facility. Do not delay for procedures when possible. • Notify receiving facility. Contact Medical Control as appropriate. • Assist ILS/ALS with Procedures. • Establish IV access with normal saline. Consider secondary IV access if time permits. • DO NOT DELAY TRANSPORT TO ESTABLISH VASCULAR ACCESS ONLY. I85 • Obtain IV access if not already established in another manner. • Consider correctable causes for arrest (H's and T's). See below. A • Consider D50 12.5-25g IV/IO for hypoglycemia • Assess rhythm and proceed to appropriate guideline: VF or Pulseless VT, PEA • Asystole. I99 • ALS preferred for all Cardiac Arrest incidents. • Assess rhythm. Continue with appropriate ACLS guidelines. -

Cardiac Protocols

6080 PEDIATRIC (AGE < 12 YEARS) CARDIAC ARREST-GENERAL PRINCIPLES General Guideline: A. Pediatric cardiac arrest more frequently represents progressive respiratory deterioration or shock rather than primary cardiac etiologies. Unrecognized deterioration may lead to bradycardia, agonal breathing, and ultimately asystole. Resulting hypoxic and ischemic insult to the brain and other vital organs make neurologic recovery extremely unlikely, even in the doubtful event that the child survives the arrest. Children who respond to rapid intervention with ventilation and oxygenation alone or to less than 5 minutes of advanced life support are much more likely to survive neurologically intact. Therefore, it is essential to recognize the child who is at risk for progressing to cardiopulmonary arrest and to provide aggressive intervention before asystole occurs Specific Information Needed For Patient Care Report A. Onset (witnessed or unwitnessed), preceding symptoms, bystander CPR, downtime before CPR and duration of CPR B. Past History: medications, medical history, suspicion of ingestion, trauma, environmental factors (hypothermia, inhalation, asphyxiation) Document Specific Objective Findings A. Unconscious, unresponsive B. Agonal, or absent respirations C. Absent pulses D. Any signs of trauma, blood loss E. Skin temperature General Treatment Guidelines A. Treat according to Pediatric BLS and ALS pulseless arrest algorithms B. Primary cardiac arrest from ventricular arrhythmia, while less common than in adults, does occur in children. If history