Eliot, As Is Well Known, Chose Conrad's Words for His Epigraph to the Hoilow Men'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

October 13, 2019 St

October 13, 2019 St. Peter the Apostle University & Community Parish The Catholic Center at Rutgers University Celebrating a Marian Year 2018-2019 SACRED HISTORY · St. Peter the Apostle University and Community Parish is one of the oldest Catholic churches in New Jersey. The Cornerstone of the Church was laid in 1856, upon the completion of the lower church, which now serves as the Parish hall and offices. WEEKEND MASS SCHEDULE: NOVENA PRAYERS: Mondays at 7:30pm in the Catholic Saturday: 9:00 a.m. Center Chapel 5:00 p.m. Vigil Sunday: 8:00 a.m., 11:00 a.m., 6:00 p.m. BAPTISMS: Normally scheduled on the second & fourth Sundays of the Holy Days of Obligation: For an updated schedule of Masses, month at 12:30pm (not during Lent). Please observe the please visit StPeterNewBrunswick.org. requirements for sponsors. Must contact the office in advance to register. First-time parents are required to attend a baptism WEEKDAY MASS SCHEDULE: formation session. Monday – Friday: 7:30 a.m. in St. Peter’s Church WEDDINGS: Monday – Thursday: 12:15 p.m. in the Catholic Center Chapel Marriage arrangements should be made one year in advance of the wedding. Please call the parish office before making CONFESSION (Sacrament of Reconciliation): other definitive plans. Once a wedding is approved and the Mondays: 12:45 - 1:30 p.m.; 7:00 p.m. - 8:00 p.m. (CC Chapel) date is confirmed, the required marriage preparation process Saturdays: 11:00 a.m. – 12:00 noon; and by appointment may commence. PASTORAL CARE OF THE SICK: EMERGENCY CONTACT INFORMATION: In the case of an emergency requiring a priest after business Please call the parish office to make arrangements for hours, please call 732-545-6185. -

Notre Dame Welcomes Dr. Judith A. Dwyer As Its 4Th President Notre

Annual Report2013-14 inside VISIONSVISIONSACADEMY of NOTREAcademy DAME of de NotreNAMUR Dame de Namur FALL 2014 NotreNotre DameDame WelcomesWelcomes Dr.Dr. JudithJudith A.A. DwyerDwyer asas itsits 4th4th PresidentPresident VISIONS MAGAZINE . FALL 2014 . 1 MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDENT How does the Notre Dame community describe excellence? I am pleased to share this combined issue of Visions and the 2013-2014 Annual Report of Gifts with you. The magazine portion highlights the academic rigor, community engagement, and spiritual depth that continue to define our tradition of educational excellence. The report testifies to the generosity of so many members of our community, who support our mission and core values. Together, they tell the story of how the Academy honors the past, celebrates the present, and secures the future in the pioneering spirit of the Sisters of Notre Dame de Namur. Judith A. Dwyer, Ph.D. How does Notre Dame describe excellence? Our students excel in academic, President artistic, and athletic achievements. Our alumnae continue to lead and achieve Eileen Wilkinson (see article on Margaret [Meg] Kane ’99, this year’s Notre Dame Award recipient, Principal on page 12). It is this legacy and dynamic learning environment that the gifts described in the Annual Report support. Jacqueline Coccia Academic Dean The “Our Time to Inspire” campaign seeks to ensure Notre Dame’s reputation Madeleine Harkins The Mansion. The Mansion continues to be a defining part of our school and our lives. as a premier Catholic academy for young women by providing an enhanced, Dean of Student Services 8 innovative, and dynamic learning environment. -

Tcjayfund.Org • Spring 2017

jay fund blitz tcjayfund.org • spring 2017 Our mission is to help families tackle childhood cancer by providing comprehensive financial, emotional and practical support. From diagnosis to recovery and beyond, we are part of the team, allowing parents to solely focus on their child’s well being. Our goal is to BE THERE for parents facing the unthinkable so they can BE THERE for their families. Coach’s Corner Dear Friends, It is great to be back in Jacksonville, and Judy and I can’t thank you enough for the warm welcome. Even though we’ve called New York home for over a decade, with our continuous work through the Jay Fund, we feel like we never left Florida. Of course, we feel the same way about the families in the NY/NJ metro region. Our goal has always been to BE THERE for the communities where I was an NFL Head Coach, and Jay Fund voices I am thrilled to continue our work in both areas. “Elijah was so touched you guys still think of him A perfect day means doing something for someone and include him even though he is not in treatment who can never repay you. A football team comes right now. As his mom, thank you for that! It has been a long struggle, one that still continues together to win a game, but through the Jay Fund, in many ways, this was a nice break and a good communities come together to help their own. time for us to enjoy as a family. “ Elijah’s mom Coming together in unity of purpose makes us stronger. -

A History of the University of Manchester Since 1951

Pullan2004jkt 10/2/03 2:43 PM Page 1 University ofManchester A history ofthe HIS IS THE SECOND VOLUME of a history of the University of Manchester since 1951. It spans seventeen critical years in T which public funding was contracting, student grants were diminishing, instructions from the government and the University Grants Commission were multiplying, and universities feared for their reputation in the public eye. It provides a frank account of the University’s struggle against these difficulties and its efforts to prove the value of university education to society and the economy. This volume describes and analyses not only academic developments and changes in the structure and finances of the University, but the opinions and social and political lives of the staff and their students as well. It also examines the controversies of the 1970s and 1980s over such issues as feminism, free speech, ethical investment, academic freedom and the quest for efficient management. The author draws on official records, staff and student newspapers, and personal interviews with people who experienced the University in very 1973–90 different ways. With its wide range of academic interests and large student population, the University of Manchester was the biggest unitary university in the country, and its history illustrates the problems faced by almost all British universities. The book will appeal to past and present staff of the University and its alumni, and to anyone interested in the debates surrounding higher with MicheleAbendstern Brian Pullan education in the late twentieth century. A history of the University of Manchester 1951–73 by Brian Pullan with Michele Abendstern is also available from Manchester University Press. -

USM Connectsvolume Two | 2018

USM ConnectsVolume Two | 2018 Inside: Career Building ■ On the job with alumni ■ Students’ hands-on learning ■ Forging a great partnership Texas Instruments’ Kayla Christy ’12, process development engineer; Chris Joyce, factory manager; and Matt Araujo ’15, process integration engineer. The Power of Partnerships How Texas Instruments’ Chris Joyce & other community leaders are teaming up with USM to build a stronger workforce. The University of Southern Maine Board of Visitors is an active group of volunteers that assists the President of the University in a range of activities that help advance the University, including public relations, government relations and fundraising. UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN MAINE BOARD OF VISITORS Chair Glenn Hutchinson ’80, ’89 Luc Nya ’96, ’99, ’08 USM Ex Officio Members Clif Greim President & CEO, Behavioral Health Program Ainsley L.N. Wallace President & CEO, Bath Savings Institution Coordinator/DOC Liaison, President & CEO, Harriman Associates Michael Hyde OCFS/Corrections Liaison USM Foundation Mark Bessire Vice President of External Affairs Tony Payne Glenn Cummings Director, & Strategic Partnerships, Senior Vice President of External President, Portland Museum of Art The Jackson Laboratory Affairs, MEMIC University of Southern Maine Roxane Cole Jon Jennings Kent Peterson Joan Cohen Founder, Portland City Manager, President & CEO, Special Assistant to the President Roxane Cole Commercial City of Portland Fluid Imaging Technologies, Inc. Real Estate, LLC Nancy Griffin Chris Joyce Aimee Petrin Vice President -

Master Plan Firm Named USGA Fails to Meet Quorum, Again

Meet Ed-Op 12 Datebook 45 Drexel’s Comes'^ 20 Golf Team Classifieds * 22 mEniuNGi£ Entertainment 24 Page 17 Volume 72, Numbet 24 Philid«lphu. P»nntylv«nu April 18,1997 The Student Newspaper at Drexel University Copyrighl 01997 The Tilingte Master USGA fails to meet quorum, again The organization has not had an official activity fee process. The draft legislative board. Plan was a compromised version, Director of Student Activities meeting this term. The activity fee process which came from two months of and USGA advisor Adam work am ong Student Life staff Goldstein said, “We would love and internal restructuring may be affected. and students. to see the student government firm Among the proposed changes, have the opportunity to vote on Anh Dang legislative officers present to do the new student fee process calls this. That is our first option.” NEWS EDITOR business. It was one officer short for a new membership and The USGA officers were named Three weeks into the spring for quorum on April 14. appointment system for the allo expected to be be informed of term, the Undergraduate Student Associate Vice President and cation committee. This process the proposal April 14, then come Government Association has not Dean of Students Dianna Dale would override parts of the cur back to debate and vote on the If approved by the yet obtained quorum to hold an and others came to USGA meet rent USGA constitution. changes the following week. If Board of Trustees, the official meeting. Currently, the ing April 14 to present their latest Modifying its constitution would USGA does not have quorum local firm will study student government needs seven proposal to revise the student require approval from the USGA See USGA on page 2 Drexel's campus with a landscape architect. -

Baby Album 2021

Baby Album 2021 A supplement to All content © 2021 Sidney Daily News. All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher, except as permitted by U.S. copyright law. 2 Friday, April 30, 2021 BABY ALBUM 2021 Sidney Daily News OH-70231090 Sidney Daily News BABY ALBUM 2021 Friday, April 30, 2021 3 Alias Jay Allison Garrett Richard Ashbrook August 27, 2020 October 2, 2020 Sidney, Ohio Piqua, Ohio Parents Parents Noah & Kaitlyn Allison Phillip & Shanda Ashbrook Grandparents Grandparents Carl & Melissa Graber Alan & Ellen Ashbrook Red & Cheri Allison Mary Grise & the late Richard Slone OH-70233033 OH-70232965 Aria Rose Barlage Weston Michael Bodenmiller November 12, 2020 March 13, 2020 Russia, Ohio Sidney, Ohio Parents Parents Kyle & Alyssa Barlage Conner & Kelsey Bodenmiller Grandparents Grandparents Mike & Carla Drees Jim & Diane Oates Jim & Elaine Barlage Mike & Sara Bodenmiller OH-70233005 OH-70232366 Owen Michael Bowers Harper Diane Brandewie October 17, 2020 March 5, 2020 Sidney, Ohio Piqua, Ohio Parents Parents Ben & Katrina Bowers Kyle & Melissa Brandewie Grandparents Grandparents Richard & Joan Steinke Greg & Melissa Bowers Tom & Bec Martin Terry & Kathy Dudley OH-70233001 OH-70233437 4 Friday, April 30, 2021 BABY ALBUM 2021 Sidney Daily News Imaan Singh Brar Aurora Robin Cathcart December 10, 2020 March 15, 2020 Sidney, Ohio Sidney, Ohio Parents Parents Jagsir Singh & Gagandeep Brar Ryan Cathcart & Amanda Burton Grandparents Grandparents Gurmeet Singh Monte & Loretta -

Noise & Capitalism

Cover by Emma (E), Mattin (M) and Sara (S) Noise & Capitalism Noise & Capitalism the interesting part, it’s an you copy another persons E: I was just thinking - you were saying that you Is it possible to try to make than male identified bodies was given at school, she is done this, quite often I have interesting challenge for drawing, where S starts what we’ve been talking weren’t sure if this would something, to capture some- writing in the book. I had studying Graphic Design. S compartmentalised my work our exchange. Now we are and I do a version, and I about, I mean I’ve talked work in relation to the as- thing in design that trans- been involved in an exhibi- sent me the work that she and friendships because I saying that you would do pass it to M, and then that about it with you and with signment you’ve been given, mits the relations produced tion called ‘Her Noise’ at and Brit Pavelson made, it is feel self-conscious or un- the design when maybe you becomes the cover. M, about the projection of because of the time, and the in making this cover? I am the South London Gallery a book that tells in both the generous perhaps. think that we should do the M: Yes it sounds interesting you as the expert and, just amount of time that you & Capitalism Noise struggling with this process in 2005, which in some way text and layout, what are the I started to project that design. -

Download a Form, Sign It, and Submit It As a Scan Electronically, Or Mail It Back

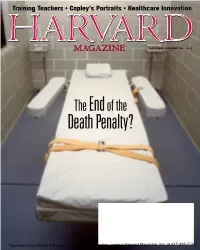

Training Teachers • Copley’s Portraits • Healthcare Innovation NOVEMBER-DECEMBER 2016 • $4.95 The End of the Death Penalty? Reprinted from Harvard Magazine. For more information, contact Harvard Magazine, Inc. at 617-495-5746 Hammond Cambridge is now RE/MAX Leading Edge Two Brattle Square | Cambridge, MA 617•497•4400 | CambridgeRealEstate.us CAMBRIDGE—Harvard Square. Two-bedroom SOMERVILLE—Ball Square. Gorgeous, renovated, BELMONT—Belmont Hill. 1936 updated Colonial. corner unit with a wall of south facing windows. 3-bed, 2.5-bath, 3-level, 1,920-square-foot town Period architectural detail. 4 bedroom. 2.5 Private balcony with views of the Charles. 24-hour house. Granite, stainless steel kitchen, 2-zone central bathrooms. C/A, 2-car garage. Private yard with concierge.. .............................................................. $1,200,000 AC, gas heat, W&D in unit, 2-car parking. ...$699,000 mature plantings. ...........................................$1,100,000 BELMONT—Lovely 1920s 9-room Colonial. 4 beds, BELMONT—Oversized, 2000+ sq. ft. house, 5 CAMBRIDGE—Delightful Boston views from private 2 baths. 2011 kitchen and bath. Period details. bedrooms, 2 baths, expansive deeded yard, newer balcony! Sunny and sparkling, 1-bedroom, upgraded Lovely yard, 2-car garage. Near schools and public gas heat and roof, off street parking. Convenient condo. Luxury amenities including 24-hour concierge, transportation. ................................................ $925,000 to train, bus to Harvard, and shops. .....$675,000 gym, pool, garage. -

Registration Is Better• J

the William Paterton eacoServing the College CommunUy^Sineen 1936 \ Vol. 49 no. 17 Wayne, New Jersey, 07470 January- 25, 1983 Registration is better• J By CHRISTINA MUELLER STAFFWRITER 'More students should take advantage of mail-in registration, according to Registrar Mark Evangelista. He said for the spring semester 9,274 out of 12,000 students used mail-in. Out of the, 9,274, 59 percent received complete schedules and 41 percent received partial schedules, Evangelista said. The 258 courses, which were cancelled* for this semester accounted for about one-third of ail partial schedules. -; -Evangelist* stated that 'approximately 3,300 students used in-person registration on Jan. 11,12, and 13. Hecontinuedtoexplara > that about 2.100 were ne»-registers and L200 were drop/ add. During in-person registration, held in the Student Center, most students had to wait on line for approximately 35 minutes." EvaBgsUsta saidth&secondandt'iird41bors_i were used to get. the students in ;rom the cold. He stated that in the Student Center students could speak with advisors, deans, and chairpersons about classes, and then register. Wayne Hail "was used for payment of tuition and fees. According to Evangelista, during late . program adjustment, held on the first two days of classes, 246 students attempted to register for classes for the first time. He said 100 percent refund of tuition and fees was still given on Jan. 17 and 18. Evangelista \ Beacon Photo by Mike Cheski added that the last day for withdrawl from The in-person registration ordeal could be a great deal less painful if more students mailed their schedules. -

Get Back on Track Continue to the Next Page ==> Ad Populos, Non Aditus, Pervenimus

We’ll Help Your Business The Westfield Leader www.goleader.com [email protected] (908) 232-4407 Get Back On Track Continue to the next page ==> Ad Populos, Non Aditus, Pervenimus Published Every Thursday Since September 3, 1890 (908) 232-4407 USPS 680020 Thursday, March 5, 2009 OUR 119th YEAR – ISSUE NO. 10-2009 Periodical – Postage Paid at Westfield, N.J. www.goleader.com [email protected] SIXTY CENTS Five Candidates Seek Three BOE Seats in WF; No SP-F, MS, GW Races By PAUL J. PEYTON this year. In addition, there are no sons he is seeking a BOE seat. Specially Written for The Westfield Leader candidates for unexpired seats in “It was more about the process AREA – Monday afternoon was Scotch Plains and Garwood. than who was redistricted and why,” the closing date for submitting appli- In Westfield, the seats of Anne Mr. Finn said. “I think I would be cations to become a candidate for Riegel, Beth Cassie and Jane Clancy remiss if I did not offer my services local school boards. The elections are up for re-election. Ms. Riegel, after what has transpired over the last will be held on Tuesday, April 21, at who is serving her ninth year on the few months (over redistricting).” which time residents will also be asked board, and board member Ms. Cassie, He also said he would like to ini- to approve local school budgets. On who has served seven years on the tiate discussion on getting Westfield Tuesday, Governor Jon Corzine ex- board, are not seeking re-election. -

The Best of the Bunch

68 / 43 THE BEST OF THE BUNCH Postseason accolades released for high school basketball players in the Magic Valley. Find a complete list on Sports 2. Partly cloudy. Business 6 REGION’S POPULATION GROWTH SLOWS >>> Twin Falls ranked 12th in state in 2008, BUSINESS 1 FRIDAY 75 CENTS March 20, 2009 MagicValley.com House SEVEN OFFICERS PUT ON LEAVE dumps Police: Three of the officers didn’t fire guns in Dunes Motel shooting Otter’s By Andrea Jackson Times-News writer gas-tax Seven Twin Falls city police officers are on paid administrative leave after the county’s third fatal police increase shooting in three years hap- pened Tuesday at the Dunes By John Miller Motel. Associated Press writer Thursday’s announce- ment was three officers BOISE — House lawmak- more than police told the ers on Thursday voted 43-27 Times-News on Tuesday to reject Gov. C.L. “Butch’’ and Wednesday. Otter’s proposed fuel tax The decision to put three hike, with foes saying the officers on leave who didn’t recession is a bad time to fire their guns but were pres- boost taxes and that Idaho ent at the incident was made should use millions of dol- Wednesday, because “we’re lars for roads from the feder- really concerned about how al stimulus first before giv- this affects our officers,”said ing the state Transportation Twin Falls Police Capt. Matt Department even more Hicks, stressing the leave is money. not disciplinary and could Under the rejected meas- end in a couple of weeks. ure, the gas tax, now 25 cents Officers “present during per gallon, would have risen the incident but not believed in three yearly steps to 32 to be involved” are: Sgt.