Facts and Figures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jorvik Medieval Festival Programme 2015

JORVIK MEDIEVAL FESTIVAL PROGRAMME 2015 Events Wednesday 19th August History at the Hall 11:00 - 16:00 I Barley Hall I Normal admission prices apply Barley Hall’s volunteer Living History team are offering visitors a special treat as they take the Hall back in time, showcasing the life of servants in the late-medieval period. Join them as they recreate the sights, sounds and smells of the household of William Snawsell, a former Lord Mayor of York and occupant of Barley Hall towards the end of the medieval period. With opportunities to meet characters, see demonstrations and take part in activities, this is a rare glimpse of social history brought to life in a fabulously atmospheric setting. Weds 19th, Thurs 20th & Fri 21st August The Canterbury Tales 19:30 I St Helen’s Church, York I £7 adult, £5 conc, £4 child Peter Carrington-Porter returns to York with his adaption of a selection of Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, including the Miller’s Tale, the Franklin’s Tale and the Pardoner’s Tale. An evening of storytelling in costume with tales of humour, romance and adventure that will take you right back to the Middle Ages! Pre-booking essential to avoid disappointment Saturday 22nd August Medieval Day at Knaresborough Castle 11:00 - 16:00 I Knaresborough Castle I Admission FREE, small cost for some activities using Medieval Coin Exchange: £1 each or 6 for £5 Who can resist a day of fun and games at a real medieval castle?! Enjoy a host of family events; for the brave young knights there are medieval sword fighting workshops, where chivalry is just as important as sword skills. -

Great Days out a Collection of Yorkshire’S Finest Attractions

FREE2017 GUIDE! Great Days Out A collection of Yorkshire’s finest attractions www.castlesandgardens.co.uk “Bringing you a whole host of ideas for great days out for all the family with our fantastic selection of formidable castles, splendid stately homes, ancient abbeys and glorious gardens.” Front cover: The Bowes Museum Beningbrough Hall, Gallery & Gardens Welcome to Yorkshire’s Great Houses, Castles & Gardens Inspiration and fun for all the family, our ‘Great Days Out’ guide presents Yorkshire’s finest collection of attractions. Read on to find out further information about each attraction, including what’s new for 2017, directions and opening times. And with a whole series of events taking place throughout the year, there is even more reason to get out and about. From plant fairs, car and steam rallies and period re-enactments to outdoor theatre, concerts and festivals there is something for everyone. To discover even more about all of the attractions in our collection, download a range of special offers, such as 2-4-1 entry, and find ideas for days out and things to do during 2017, visit www.castlesandgardens.co.uk. Bolton Abbey 03 Getting around Yorkshire Symbols Once you’re in Yorkshire there are plenty of options for getting around, whether you prefer your own pedal National Trust property power, sitting back on a train or bus or exploring scenic back roads by car. By Bicycle English Heritage property Following on from the huge success of the magnificent Tour De France and annual Tour De Yorkshire, cycling has never been so popular. Quiet country roads, byways and a network of cycle paths, there’s a lot to see and do, so get on your bike and Yorkshire In Bloom Attractions discover Yorkshire from your saddle. -

FREE ATTRACTIONS – All Attractions Below Are Free with Your Yorkcard

York Residents’ Festival 2014 www.visityork.org/residentsfestival FREE ATTRACTIONS – all attractions below are free with your YorkCard. All Saints North Street NEW The Shrine and Parish Church of All Saints North Street 01904 728122 [email protected] www.allsaints-northstreet.org.uk Saturday 25 January York’s Finest Medieval Church 10.00am Guided tour of the world famous stained glass 11.00am Tour of the Lady Chapel, hear about the archaeology, restoration and production of medieval floor tiles. 12.00pm Sing the Angelus 4.30pm Talk about York’s finest medieval church 5pm Illuminated Latin Vespers (Gregorian Chant) with multimedia light display. Pre-booking is not required. The Bar Convent Blossom Street 01904 6433238 Saturday 25 January 10.00am – 4.00pm York’s hidden gem, established in 1686. Visit the free museum and fabulous cafe. Pre-booking is not required. Barley Hall 2 Coffee Yard, off Stonegate 01904 615505 [email protected] www.barleyhall.co.uk Saturday 25 & Sunday 26 January 10.00am – 4.00pm (last admission) Barley Hall is a stunning medieval townhouse once home to the Priors of Nostell and the Mayor of York. Discover a very horrid history of ‘Plague, Poverty and Prayer’ at our latest exhibition created in partnership with Horrible Histories author Terry Deary. Pre-booking is not required. Bedern Hall Bedern 01904 653698 [email protected] www.bedernhall.co.uk Sunday 26 January, 10.30am – 4.30pm Learn about plans for the Bedern Hall Foundation – a new vision for this popular meetings, dining and wedding venue based on Education, Preservation & Accessibility. -

Ricardian Bulletin

Ricardian Bulletin Contents Summer 2006 2 From the Chairman 3 Society News and Notices 6 Media Retrospective 8 News and Reviews 11 Celebrating 50 Years: The Events - update 12 The Schools Competition 15 Celebrating with Isolde: a vice-president is honoured by Phil Stone 17 Troops and Tactics by Bill Featherstone 25 Ricardian Heroes: George Awdry by John Saunders 29 The Leicester Statue by Elizabeth Nokes 32 Memories from the North by Mary O’Regan 35 The Society’s Earliest Members 36 News from Barley Hall 38 The Biographical Index by Ian Rogers 39 The Man Himself 41 The Debate: Who murdered the Princes? 48 Hastings and the News from Stony Stratford by Gordon Smith 50 Logge Notes and Queries: by Lesley Boatwright 53 I Take You, Anne, With All Your Lands … by Moira Habberjam 55 Beyond The Papal Pale or Simply the Wrong Sort of Affinity? Part 1 by Marie Barnfield 58 Postscript to Louis XI’s Lost Effigy by Geoffrey Wheeler 59 ‘Things they never said’ by Brian Wainwright 60 Correspondence 68 The Barton Library 69 Book Review 70 Letter from New South Wales 72 Report on Society Events 77 Future Society Events 79 Branches and Groups 85 New Members 87 Obituaries and Recently Deceased Members 88 Calendar Contributions Contributions are welcomed from all members. Articles and correspondence regarding the Bulletin Debate should be sent to Peter Hammond and all other contributions to Elizabeth Nokes. Bulletin Press Dates 15 January for Spring issue; 15 April for Summer issue; 15 July for Autumn issue; 15 October for Winter issue. -

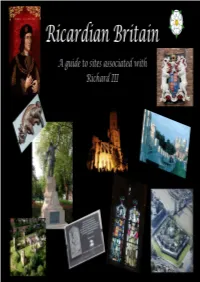

Introduction

Introduction Much is owed to the previous authors, Val Alliez and Carolyn Hammond. We thank them for laying the foundations upon which this new edition has been built. Thanks go, too, to those members of the Richard III Society who responded to the call for suggestions of sites not previously included. Unlike previous editions, the country has been divided into regions, the divisions being taken from the pattern set out by the National Trust. This explains why Hertfordshire is included in the East of England. The web edition has been designed to be a flexible tool which can be updated as necessary. We hope that this guide will enable members and visitors alike to visit and enjoy places that are associated with Richard III and the people he knew. Guidelines This edition of Ricardian Britain was designed for web and Wi-Fi devices such as smart phones or mp3 players with Wi-Fi capabilities. Some of the features include: • Addresses with postcodes, and telephone numbers • Website addresses • e-mail addresses When available, specific postcodes are included to access maps and directions via GPS/SatNav devices. Several organisations have provided APPs. Users are directed to each website for opening hours, entrance fees, and additional information such as photographs, directions, restaurants, accessibility, parking, etc. about the site. Please note that some sites are closed during certain months of the year. Many are open only between Easter and September/October. The visiting of churches and other religious institutions is subject to the timing of services. Some sites may be closed for special events such as weddings, etc. -

41St Annual Report 2012–13 the Trust’S Mission

York Archaeological Trust 41st Annual Report 2012–13 The Trust’s Mission York Archaeological Trust, recognising the exceptional importance of York’s historic environment, will provide and promote archaeology of the highest possible standards in York, its region and beyond. By excellence in archaeological discovery, research, conservation, curation, academic dissemination and through training, education and widely accessible public presentation, the Trust, an educational charity, will maximise the public benefits of archaeology. Published by York Archaeological Trust © York Archaeological Trust 2013 A Company Limited by Guarantee without share capital registered in England Number 1430801 Registered Charity in England & Wales (No.509060) and Scotland (SCO42846) ISBN No: 978-1 874454 66 3 Printed by B&B Press, Parkgate, Rotherham York Archaeological Trust 2012–2013 41st Annual Report Contents Chairman's Report 2 Chief Executive 3 Archaeology 4 Excavation and Fieldwork 5 Hungate 5 ArcHeritage 7 1 Northlight Heritage 10 Trent & Peak Archaeology 13 Archaeological Research and Development 17 Artefact Research 18 Curatorial Department 19 Conservation Laboratory & Archaeological Wood Centre 21 Archaeology and the Public Publications, Archive and Library 23 Education and Training 25 Community Archaeology 26 Attractions and Events JORVIK 27 DIG 29 Barley Hall 30 Micklegate Bar 31 Events and Festivals 32 The Year Ahead 34 Finance, Management and Administration Trustees' Statement on the Summarised Financial Statements 35 Financial Review 2011–12 36 -

Uk-Staff-Relocation-Handbook.Pdf

Relocation 2016 / 2017 handbook Welcome to the University This handbook is aimed at staff joining the University from within the United Kingdom. We hope the information included in this guide will help make your move to York easier. We have links throughout to provide in depth information on a range of topics and to support you in your transition. The Welcome Service The Welcome Service is a tailored support service and is available to all new staff who need to relocate in order to take up their post at the university. Our welcome team offer practical support and advice on all aspects of relocation including: accommodation, schools, banking, transport and the University. If you would like to use the Welcome Service, email the scheme coordinator at welcome- [email protected] We look forward to welcoming you to the University. Paula Tunbridge Acting Director of Human Resources 2 3 Contents Preparing for your arrival Getting to know York Initial funds Shopping Getting to York Eating out Short term accommodation Things to do in York Your first few weeks Entertainment Sports, leisure and fitness Finding long term accommodation Outside of York Shipping your belongings Settling in York Working at the University Getting to know the campus Utilities Travelling to work Telephone & broadband Eateries on campus TV license Shops and banks Council tax Prayer facilities Insurance Disability Registering with a doctor and dentist Unions Private health care Getting paid Emergency healthcare Pensions schemes Bringing your family Employee benefits Planning for your families arrival Schools Pre-schools and nurseries Bringing a pet Family network 4 5 Preparing for your arrival Once you have received your offer of appointment Initial funds you can begin to prepare for your arrival. -

The Ricardian and the Bulletin Are Available from Judith Ridley

Ricardian Bulletin Contents Winter 2006 2 From the Chairman 4 The Robert Hamblin Award 2006 5 Society News and Notices 11 Media Retrospective 14 News and Reviews 20 Celebrating 50 Years: Members’ Weekend and AGM 29 Celebrating 50 Years: Chivalry, the Order of the Garter and St George’s Chapel 39 Ricardian Heroes: by John Saunders 42 The Guildhall Dinner: by John Saunders 43 Memories from the Early Days: by Val Alliez 44 Our Longest Serving Members 45 The Man Himself by Keith Dockray 47 An Adventure in Historical Research: by Toni Mount 49 Constabulary Duty: by BM Cron 52 Cirencester Parish Church: by Gwen and Brian Walter 54 Completing the Set: Henry VIII’s Other Wives: by Stephen Lark 55 Logge Notes and Queries: by Lesley Boatwright 57 Translation service 58 On the Horns of a Bosworth Legend Dilemma: by Randolph Jones 60 Review Article by Helen Cox 62 Annual Report of the Richard III and Yorkist History Trust 63 Correspondence 69 The Barton Library 71 Letter from America: An American Member’s View of the AGM 74 Report on Society Events 79 Future Society Events 82 Branches and Groups 86 Palaeography by Post 87 New Members 88 Calendar Contributions Contributions are welcomed from all members. All contributions should be sent to the Technical Editor, Lynda Pidgeon. Bulletin Press Dates 15 January for Spring issue; 15 April for Summer issue; 15 July for Autumn issue; 15 October for Winter issue. Articles should be sent well in advance. Bulletin & Ricardian Back Numbers Back issues of the The Ricardian and The Bulletin are available from Judith Ridley. -

Ricardian Bulletin Is Produced by the Bulletin Editorial Committee, General Editor Elizabeth Nokes, and Printed by St Edmundsbury Press

Ricardian Bulletin Winter 2005 Contents 2 From the Chairman 4 The Robert Hamblin Award 2005 5 Celebrating 50 Years: The Programme 9 Society News and Notices 15 The Executive Committee: Who we are and what we are doing 16 A Gateway to the Fifteenth Century: Improvements to the Society’s website 18 Media Retrospective 19 News and Reviews 22 News from Barley Hall 24 Richard III & Yorkist History Trust Annual Report 26 The Man Himself 27 The Debate: Historical Novels: A good thing or not? 30 Logge Notes and Queries: Education, Education, Education by L Wynne-Davies 32 Battling for Bosworth by A D White 35 Irving, Cibber and Richard III by Angela Moreton 38 Richard III’s Christmas by John Ashdown-Hill 40 Correspondence 42 The Barton Library 45 Letter from America 47 Report on Society Events 51 Future Society Events 53 Branches and Groups Contacts 55 Branches and Groups Reports 61 New Members 62 Obituaries 64 Calendar Contributions Contributions are welcomed from all members. Articles and correspondence regarding the Bulletin Debate should be sent to Peter Hammond and all other contributions to Elizabeth Nokes. Bulletin Press Dates 15 January for Spring issue; 15 April for Summer issue; 15 July for Autumn issue; 15 October for Winter issue. Articles should be sent well in advance. Bulletin & Ricardian Back Numbers Back issues of The Ricardian and Bulletin are available from Judith Ridley. If you are interested in obtaining any back numbers, please contact Mrs Ridley to establish whether she holds the issue(s) in which you are interested. For contact details see back inside cover of the Bulletin The Ricardian Bulletin is produced by the Bulletin Editorial Committee, General Editor Elizabeth Nokes, and printed by St Edmundsbury Press. -

Tape Library – Conditions of Hire

TAPE LIBRARY – CONDITIONS OF HIRE The audio cassettes have been copied from the original recordings in approximate chronological order, as listed in the catalogue, or grouped together under similar subject matter, with shorter items combined on one tape. Transfers can be made onto CDs (UK) on request – please allow adequate time / advance notice. Please order by title of talk or broadcast. As duplicates exist only for the more popular items, it would be appreciated if an alternative choice could be given, where possible. If specific tapes are required for definite dates of branch/group meetings, etc., please reserve well in advance. When ordering please print: Your full name, address, including postal code, in BLOCK CAPITALS. Periods of hire: U.K. and Europe: up to 14 days. Overseas: up to 4 weeks. (Loans can be extended provided items are not required by other members.) Postage: Borrower is responsible for outward and return postage (which should be by airmail outside U.K.). When you return tapes, please enclose stamps in the parcel to refund the cost of the outward postage. Please take care of cassettes/CDs supplied. Protect from dust, heat and humidity, strong magnetic fields, etc. Members will be asked to bear the cost of replacement for lost or damaged tapes. Please note: tapes are supplied for private usage only, i.e. by individual Society members, or for private meetings of branches or groups. They may not be used for any kind of public performance. GEOFFREY WHEELER, 195, GLOUCESTER PLACE, LONDON, NW1 6BU. Tel: [020 7724 5842] 1 1950’s WOMAN’S HOUR BBC Radio: Interview with Stephen Usherwood historian, and Isolde Wigram (Former Secretary &Vice President, Richard III Society).