Darfur Peace Process Chronology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sudan a Country Study.Pdf

A Country Study: Sudan An Nilain Mosque, at the site of the confluence of the Blue Nile and White Nile in Khartoum Federal Research Division Library of Congress Edited by Helen Chapin Metz Research Completed June 1991 Table of Contents Foreword Acknowledgements Preface Country Profile Country Geography Society Economy Transportation Government and Politics National Security Introduction Chapter 1 - Historical Setting (Thomas Ofcansky) Early History Cush Meroe Christian Nubia The Coming of Islam The Arabs The Decline of Christian Nubia The Rule of the Kashif The Funj The Fur The Turkiyah, 1821-85 The Mahdiyah, 1884-98 The Khalifa Reconquest of Sudan The Anglo-Egyptian Condominium, 1899-1955 Britain's Southern Policy Rise of Sudanese Nationalism The Road to Independence The South and the Unity of Sudan Independent Sudan The Politics of Independence The Abbud Military Government, 1958-64 Return to Civilian Rule, 1964-69 The Nimeiri Era, 1969-85 Revolutionary Command Council The Southern Problem Political Developments National Reconciliation The Transitional Military Council Sadiq Al Mahdi and Coalition Governments Chapter 2 - The Society and its Environment (Robert O. Collins) Physical Setting Geographical Regions Soils Hydrology Climate Population Ethnicity Language Ethnic Groups The Muslim Peoples Non-Muslim Peoples Migration Regionalism and Ethnicity The Social Order Northern Arabized Communities Southern Communities Urban and National Elites Women and the Family Religious -

The Fall of Al-Bashir: Mapping Contestation Forces in Sudan

Bawader, 12th April 2019 The Fall of al-Bashir: Mapping Contestation Forces in Sudan → Magdi El-Gizouli Protests in Khartoum calling for regime change © EPA-EFE/STR What is the Sudanese Professionals Association (SPA) anyway, perplexed commentators and news anchors on Sudan’s government-aligned television channels asked repetitively as if bound by a spell? An anchor on the BBC Arabic Channel described the SPA as “mysterious” and “bewildering”. Most were asking about the apparently unfathomable body that has taken the Sudanese political scene by surprise since December 2018 when the ongoing wave of popular protests against President Omar al-Bashir’s 30-year authoritarian rule began. The initial spark of protests came from Atbara, a dusty town pressed between the Nile and the desert some 350km north of the capital, Khartoum. A crowd of school pupils, market labourers and university students raged against the government in response to an abrupt tripling of the price of bread as a result of the government’s removal of wheat subsidies. Protestors in several towns across the country set fire to the headquarters of the ruling National Congress Party (NCP) and stormed local government offices and Zakat Chamber1 storehouses taking food items in a show of popular sovereignty. Territorial separation and economic freefall Since the independence of South Sudan in 2011, Sudan’s economy has been experiencing a freefall as the bulk of its oil and government revenues withered away almost overnight. Currency depreciation, hyperinflation and dwindling foreign currency reserves coupled with the rise in the prices of good and a banking crisis with severe cash supply shortages, have all contributed to the economic crisis. -

The Foreign Military Presence in the Horn of Africa Region

SIPRI Background Paper April 2019 THE FOREIGN MILITARY SUMMARY w The Horn of Africa is PRESENCE IN THE HORN OF undergoing far-reaching changes in its external security AFRICA REGION environment. A wide variety of international security actors— from Europe, the United States, neil melvin the Middle East, the Gulf, and Asia—are currently operating I. Introduction in the region. As a result, the Horn of Africa has experienced The Horn of Africa region has experienced a substantial increase in the a proliferation of foreign number and size of foreign military deployments since 2001, especially in the military bases and a build-up of 1 past decade (see annexes 1 and 2 for an overview). A wide range of regional naval forces. The external and international security actors are currently operating in the Horn and the militarization of the Horn poses foreign military installations include land-based facilities (e.g. bases, ports, major questions for the future airstrips, training camps, semi-permanent facilities and logistics hubs) and security and stability of the naval forces on permanent or regular deployment.2 The most visible aspect region. of this presence is the proliferation of military facilities in littoral areas along This SIPRI Background the Red Sea and the Horn of Africa.3 However, there has also been a build-up Paper is the first of three papers of naval forces, notably around the Bab el-Mandeb Strait, at the entrance to devoted to the new external the Red Sea and in the Gulf of Aden. security politics of the Horn of This SIPRI Background Paper maps the foreign military presence in the Africa. -

Reference Projects

REFERENCE PROJECTS Project Locations around the World © HPC Hamburg Port Consulting GmbH On the following pages, you will find a comprehensive list of the projects HPC has conducted ever since our foundation in 1976. 22/07/2021 HPC Hamburg Port Consulting GmbH 1/94 REFERENCE PROJECTS Project Title Client, Location Start Date Construction Supervision for Six Automated Victoria International Container Terminal 2021 Container Carriers in Melbourne, Australia Ltd. PR-3241/336003 Melbourne; Australia Application for Funding of 5G Campus HHLA Hamburger Hafen und Logistik AG 2021 Network Hamburg; Germany PR-3240/331014 Simulation Analysis Study for CTA with Fully HHLA Hamburger Hafen und Logistik AG 2021 Automated Truck Handover Hamburg; Germany PR-3238/331013 Initial Market Study for a New "Condition EMG Automation GmbH 2021 Monitoring & Predictive Maintenance" Wenden; Germany PR-3239/332005 Business Model Support with Funding Applications for the B- HHLA Hamburger Hafen und Logistik AG 2021 AGV System at Container Terminal Hamburg; Germany PR-3233/331011 Burchardkai HPC Secondment BHP Safe Mooring IPS Aurecon Australasia Pty Ltd 2021 Melbourne; Australia PR-3236/336002 Brazil, Sagres Implementation of OHS Sagres Operacoes Portuarias Ltda 2021 Recommendations Cidade Nova Rio Grande RS; Brazil PR-3234/334002 IT Management Support for a German CHI Deutschland Cargo Handling GmbH 2021 Cargo Handling Company Frankfurt/Main; Germany PR-3235/332004 PANG Study on the Ability of Ports on the Puerto Angamos 2021 Western Coast of Latin America to Handle -

No. ICC-02/05-02/09 24 September 2009 1 Original

ICC-02/05-02/09-91-Red 25-09-2009 1/33 EO PT Original: English No .: ICC-02/05-02/09 Date: 24 September 2009 PRE-TRIAL CHAMBER I Before: Judge Sylvia Steiner, Presiding Judge Judge Sanji Mmasenono Monageng Judge Cuno Tarfusser SITUATION IN DARFUR, THE SUDAN IN THE CASE OF THE PROSECUTOR V. BAHAR IDRISS ABU GARDA Public Redacted Version of Prosecution’s “DOCUMENT CONTAINING THE CHARGES SUBMITTED PURSUANT TO ARTICLE 61(3) OF THE STATUTE” filed on 10 September 2009 Source: Office of the Prosecutor No. ICC-02/05-02/09 1 24 September 2009 ICC-02/05-02/09-91-Red 25-09-2009 2/33 EO PT Document to be notified in accordance with regulation 31 of the Regulations of the Court to: The Office of the Prosecutor Counsel for the Defence Karim A. A. Khan Legal Representatives of Victims Legal Representatives of Applicants Unrepresented Victims Unrepresented Applicants for Participation/Reparation The Office of Public Counsel for Victims The Office of Public Counsel for the Defence States Representatives Amicus Curiae REGISTRY Registrar Defence Support Section Ms Silvana Arbia Victims and Witnesses Unit Detention Section Victims Participation and Reparations Other Section No. ICC-02/05-02/09 2 24 September 2009 ICC-02/05-02/09-91-Red 25-09-2009 3/33 EO PT I. THE PERSON CHARGED................................................................................................................ 5 II. STATEMENT OF FACTS .................................................................................................................... 6 A. BACKGROUND ................................................................................................................................ -

Sudan Liberation Army-Abdul Wahid (SLA-AW)

Sudan Liberation Army-Abdul Wahid (SLA-AW) Origins/composition The SLA was formed in 2001 by an alliance of Fur and Zaghawa. From the start, the two had markedly different agendas. The Fur leaders of the SLA supported the democratic, decentralized ‘New Sudan’ advocated by the Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA) and envisaged their rebellion as being essentially anti-government. Most Zaghawa wanted to organize not against the government but against the Arab militias with whom they were in competition in North Darfur, including over the lucrative camel trade. By the end of 2002, tensions were running deep. In mid-2004, the Zaghawa attacked the Fur heartland, Jebel Marra. Since then the movement has split into a dozen factions, largely along tribal lines. All attempts to reunify it have failed. Leadership Abdul Wahid Mohamed al Nur, the original chairman of the SLA, is a Khartoum- educated lawyer who since the beginning of the insurgency has spent more time outside Darfur than inside. Increasingly contested by his own commanders because of his erratic, micromanaging style of leadership and failure to establish institutions, Abdul Wahid settled in Paris when the Abuja peace talks ended in 2006. Despite France’s support, he refused to engage in internationally-sponsored peace talks and often refused even to meet high-level visitors—including prominent members of his own tribe who had travelled from Sudan for the sole purpose of engaging with him. Abdul Wahid remained in Paris until the end of 2010, when he moved to Nairobi and began shuttling between Kenya and Uganda. Although his departure from Paris was depicted as a move to engage SLA commanders in consultations to reorganize the movement, it was in reality prompted by a French government decision not to renew his residency. -

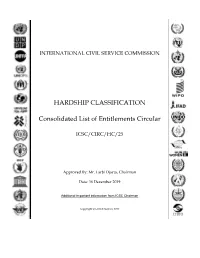

HARDSHIP CLASSIFICATION Consolidated List of Entitlements Circular

INTERNATIONAL CIVIL SERVICE COMMISSION HARDSHIP CLASSIFICATION Consolidated List of Entitlements Circular ICSC/CIRC/HC/25 Approved By: Mr. Larbi Djacta, Chairman Date: 16 December 2019 Additional important information from ICSC Chairman Copyright © United Nations 2017 United Nations International Civil Service Commission (HRPD) Consolidated list of entitlements - Effective 1 January 2020 Country/Area Name Duty Station Review Date Eff. Date Class Duty Station ID AFGHANISTAN Bamyan 01/Jan/2020 01/Jan/2020 E AFG002 AFGHANISTAN Faizabad 01/Jan/2020 01/Jan/2020 E AFG003 AFGHANISTAN Gardez 01/Jan/2020 01/Jan/2020 E AFG018 AFGHANISTAN Herat 01/Jan/2020 01/Jan/2020 E AFG007 AFGHANISTAN Jalalabad 01/Jan/2020 01/Jan/2020 E AFG008 AFGHANISTAN Kabul 01/Jan/2020 01/Jan/2020 E AFG001 AFGHANISTAN Kandahar 01/Jan/2020 01/Jan/2020 E AFG009 AFGHANISTAN Khowst 01/Jan/2019 01/Jan/2019 E AFG010 AFGHANISTAN Kunduz 01/Jan/2020 01/Jan/2020 E AFG020 AFGHANISTAN Maymana (Faryab) 01/Jan/2020 01/Jan/2020 E AFG017 AFGHANISTAN Mazar-I-Sharif 01/Jan/2020 01/Jan/2020 E AFG011 AFGHANISTAN Pul-i-Kumri 01/Jan/2020 01/Jan/2020 E AFG032 ALBANIA Tirana 01/Jan/2019 01/Jan/2019 A ALB001 ALGERIA Algiers 01/Jan/2018 01/Jan/2018 B ALG001 ALGERIA Tindouf 01/Jan/2018 01/Jan/2018 E ALG015 ALGERIA Tlemcen 01/Jul/2018 01/Jul/2018 C ALG037 ANGOLA Dundo 01/Jul/2018 01/Jul/2018 D ANG047 ANGOLA Luanda 01/Jul/2018 01/Jan/2018 B ANG001 ANTIGUA AND BARBUDA St. Johns 01/Jan/2019 01/Jan/2019 A ANT010 ARGENTINA Buenos Aires 01/Jan/2019 01/Jan/2019 A ARG001 ARMENIA Yerevan 01/Jan/2019 01/Jan/2019 -

Sanganeb Atoll, Sudan a Marine National Park with Scientific Criteria for Ecologically Significant Marine Areas Abstract

Sanganeb Atoll, Sudan A Marine National Park with Scientific Criteria for Ecologically Significant Marine Areas Abstract Sanganeb Marine National Park (SMNP) is one of the most unique reef structures in the Sudanese Red Sea whose steep slopes rise from a sea floor more than 800 m deep. It is located at approximately 30km north-east of Port Sudan city at 19° 42 N, 37° 26 E. The Atoll is characterized by steep slopes on all sides. The dominated coral reef ecosystem harbors significant populations of fauna and flora in a stable equilibrium with numerous endemic and endangered species. The reefs are distinctive of their high number of species, diverse number of habitats, and high endemism. The atoll has a diverse coral fauna with a total of 86 coral species being recorded. The total number of species of algae, polychaetes, fish, and Cnidaria has been confirmed as occurring at Sanganeb Atoll. Research activities are currently being conducted; yet several legislative decisions are needed at the national level in addition to monitoring. Introduction (To include: feature type(s) presented, geographic description, depth range, oceanography, general information data reported, availability of models) Sanganeb Atoll was declared a marine nation park in 1990. Sanganeb Marine National Park (SMNP) is one of the most unique reef structures in the Sudanese Red Sea whose steep slopes rise from a sea floor more than 800 m deep (Krupp, 1990). With the exception of the man-made structures built on the reef flat in the south, there is no dry land at SMNP (Figure 1). The Atoll is characterized by steep slopes on all sides with terraces in their upper parts and occasional spurs and pillars (Sheppard and Wells, 1988). -

Sudan's Infrastructure: a Continental Perspective

COUNTRY REPORT Sudan’s Infrastructure: A Continental Perspective Rupa Ranganathan and Cecilia Briceño-Garmendia JUNE 2011 © 2011 The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank 1818 H Street, NW Washington, DC 20433 USA Telephone: 202-473-1000 Internet: www.worldbank.org E-mail: [email protected] All rights reserved A publication of the World Bank. The World Bank 1818 H Street, NW Washington, DC 20433 USA The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Executive Directors of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Rights and permissions The material in this publication is copyrighted. Copying and/or transmitting portions or all of this work without permission may be a violation of applicable law. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank encourages dissemination of its work and will normally grant permission to reproduce portions of the work promptly. For permission to photocopy or reprint any part of this work, please send a request with complete information to the Copyright Clearance Center Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923 USA; telephone: 978-750-8400; fax: 978-750-4470; Internet: www.copyright.com. -

Explaining the Darfur Peace Agreement – May 2006

Explaining the Darfur Peace Agreement – May 2006 An open letter to those members of the movements who are still reluctant to sign from the African Union moderators We are writing this open letter to our dear friends and colleagues in the Sudan Liberation Movement/Army and Justice and Equality Movement, who are hesitating to support the Darfur Peace Agreement that was presented by the African Union Mediation to the Parties on 25 April, and which was enhanced with the support of the United States, United Kingdom, Canada and the European Union, and signed by Dr. Magzoub el Khalifa on behalf of the Government of Sudan and Mr. Minni Arkoy Minawi on behalf of the Sudan Liberation Movement/Army, on 5 May. Although we are members of the Mediation Team in Abuja, we are writing this as individuals who are deeply concerned with the situation in Darfur and committed to bringing about peace. We are concentrating on the actual paragraphs of the Darfur Peace Agreement, explaining its provisions, rather than exploring the wider political context and choices facing the leaders of the Movements. We believe that the Darfur Peace Agreement represents a good deal for the Movements and for the people of Darfur. It is not perfect and it does not meet all the aspirations of the Movements. But it is a very strong deal in each of three main areas: power-sharing, wealth-sharing and security arrangements. And the Darfur Peace Agreement has stronger guarantees for implementation than any other peace agreement in this African continent. In this open letter, let us explain some of the most important provisions of the Darfur Peace Agreement. -

Abdul Rasoul's Personal Vendetta Against President Of

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by MURAL - Maynooth University Research Archive Library Abdul Rasoul’s Personal Vendetta against President of JEM 10th, June 2009, 12:40 am Abdul Rasoul’s Personal Vendetta against President of JEM By: Abdullahi Osman El-Tom Izzadine Abdul Rasoul’s “Dr. Khalil Ibrahim an empty bravado” was referred to me by several friends for comments. The article was published in the reputable venue “Sudan Tribune”, May 2009. I was reluctant to respond to the article for several reasons. Although Abdu Rasoul signed himself as Managing Editor of the Citizen Newspaper- Sudan, the article is steeped in amateur journalism that bedevils many of Sudanese newspapers. To begin with, the author fails to distinguish between facts and government propaganda, a rather embarrassing flaw for a managing editor of a newspaper. Instead of focusing on substance, the author dwells on a personal vendetta against Dr. Khalil Ibrahim and his brother Gibril Ibrahim (hence Khalil and Gibril). The connecting the two together skews the article away from focussing on a major regional and national issue and turns it into a personal assault on a family. Much worse, the author displays an incredible level of laziness and lack of aptitude for research as evidenced by the fact that the work is based on readily available rumours rather than time spent gathering hard facts. The author describes Khalil as an “Islamist fundamentalist”, whose “problem with the current regime in Khartoum is not ideological rather that of power positions [ie. A fight over power and jobs]”. -

Nasty Neighbors Resolving the Chad–Sudan Proxy War

www.enoughproject.org NASTY NEIGHBORS Resolving the Chad–Sudan Proxy War By Colin Thomas-Jensen ENOUGH Strategy Paper 17 April 2008 t’s bad enough that the international commu- Peacemaking: The United States and key part- nity has failed, five years in, to end the geno- ners—such as France, the United Kingdom, China, Icide in Darfur, and worse still that it reacted the European Union, the United Nations, and the with no urgency when the Darfur crisis bled into African Union—must commit adequate diplomatic neighboring Chad. With the root causes of conflict and financial resources to a major peace initiative in each country still untended, this regional crisis for Sudan and Chad. A full-court diplomatic press is poised to deepen. to resolve the conflict in Darfur must be matched with efforts to bring about profound political The agreement signed on March 13 in Dakar, Sen- changes inside Chad and, ultimately, end the proxy egal, between Chadian President Idriss Déby and war between Sudan and Chad.1 Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir might have ap- peared a spot of good news for a part of the world Protection: The international community must that has been on a steady slide toward chaos. It take steps to protect civilians by expediting the wasn’t. Relations between Chad and Sudan are so full deployment of the joint U.N./EU hybrid mission volatile and international diplomacy so feeble that to Chad and the hybrid U.N./AU mission to Darfur. a non-aggression pact between the two countries The U.N.