Knowing the Country

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NUCLEAR POWER: MIRACLE OR MELTDOWN Jim Green

URANIUM MINING This PowerPoint is posted at www. tiny.cc /c1xwb URANIUM weighing benefits and problems BENEFITS Jobs Export revenue Climate change? PROBLEMS Environmental impacts ‘Radioactive racism’CLIMATE CHANGE? Nuclear weapons proliferation Nuclear power risks e.g. reactor accidents, attacks on nuclear plants JOBS 1750 = <0.02% of all jobs in Australia EXPORT REVENUE $751 million in 2009 -10 Uranium accounts for about one-third of one percent of Australian export revenue … 0.38% in 2007 0.36% in 2008/09 Approx. 0.25% in 2009/10 CLIMATE CHANGE BENEFITS OF URANIUM AND NUCLEAR POWER? Greenhouse emissions intensity (Grams CO2-e / kWh) Coal 1200 Nuclear 66 Wind 22 Does Australian uranium reduce global greenhouse emissions? The answer depends on whether Australian uranium displaces i) alternative uranium sources ii) more greenhouse-intensive energy sources (e.g. coal) iii) less greenhouse-intensive energy sources (e.g. wind power) CLIMATE CHANGE BENEFITS OF URANIUM AND NUCLEAR POWER? OLYMPIC DAM MINE Greenhouse emissions projected to increase to 5.9 million tonnes annually. This will make it impossible for South Australia to reach its legislated emissions target of 13 million tonnes annually by 2050. URANIUM weighing benefits and problems BENEFITS Jobs <0.02% Export revenue $ ~0.33% Climate change? benefits compared to fossil fuels but not renewables PROBLEMS Environmental impacts Nuclear weapons proliferation risks ‘Radioactive racism’ Nuclear power risks e.g. reactor accidents, attacks on nuclear plants Olympic Dam mine fire, 2001 Radioactive tailings, Olympic Dam Radioactive tailings, Olympic Dam Leaking tailings dam, Olympic Dam, 2008 BHP Billiton threatened “disciplinary action” against any workers caught taking photos of the mine site. -

Canning Stock Route & Gunbarrel Highway

CANNING STOCK ROUTE & GUNBARREL HIGHWAY Tour & Tag Along Option Pat Mangan Join us on this fully guided 4WD small group adventure tour. Travel as a passenger in one of our 4WD vehicles or use your own 4WD Tag Along vehicle as you join our experienced guides exploring the contrasting and arid outback of Australia. Visit iconic & remote areas such as the Canning Stock Route & Gunbarrel Highway, see Uluru, Durba Springs, 2 night stay at Carnegie Station, Giles Meteorological Station, the “Haunted Well” – Well 37, Len Beadell’s Talawana Track & the Tanami Track - ending your adventure in Alice Springs. 21 Days Dep 15 Jun 2021 DAY 1: Tue 15 Jun ARRIVE AT AYERS ROCK RESORT T (-) Clients to have own travel arrangements to Ayers Rock, Northern Territory. Please check-in by 5:00pm where you will meet your crew and fellow passengers for a tour briefing. Overnight: Ayers Rock Campground • □ DAY 2: Wed 16 Jun AYERS ROCK - GILES 480km T (BLD) Depart this morning at 9:00am and pass by Ayers Rock and take a short walk into Olga Gorge before our journey west along the new Gunbarrel Highway to the WA border and beyond. Visit Lasseter's cave, where this exocentric miner camped after his alleged discovery of a reef of gold. Then on through the Petermann Ranges to WA and Giles. Overnight: Giles • □ DAY 3: Thu 17 Jun GILES – WARBURTON 180km T (BLD) A morning outside viewing of the Meteorological Station. See Beadell’s grader that opened up the network of outback roads in the 1950's and 60's including the infamous Gunbarrel Highway. -

Re-Awakening Languages: Theory and Practice in the Revitalisation Of

RE-AWAKENING LANGUAGES Theory and practice in the revitalisation of Australia’s Indigenous languages Edited by John Hobson, Kevin Lowe, Susan Poetsch and Michael Walsh Copyright Published 2010 by Sydney University Press SYDNEY UNIVERSITY PRESS University of Sydney Library sydney.edu.au/sup © John Hobson, Kevin Lowe, Susan Poetsch & Michael Walsh 2010 © Individual contributors 2010 © Sydney University Press 2010 Reproduction and Communication for other purposes Except as permitted under the Act, no part of this edition may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or communicated in any form or by any means without prior written permission. All requests for reproduction or communication should be made to Sydney University Press at the address below: Sydney University Press Fisher Library F03 University of Sydney NSW 2006 AUSTRALIA Email: [email protected] Readers are advised that protocols can exist in Indigenous Australian communities against speaking names and displaying images of the deceased. Please check with local Indigenous Elders before using this publication in their communities. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Re-awakening languages: theory and practice in the revitalisation of Australia’s Indigenous languages / edited by John Hobson … [et al.] ISBN: 9781920899554 (pbk.) Notes: Includes bibliographical references and index. Subjects: Aboriginal Australians--Languages--Revival. Australian languages--Social aspects. Language obsolescence--Australia. Language revival--Australia. iv Copyright Language planning--Australia. Other Authors/Contributors: Hobson, John Robert, 1958- Lowe, Kevin Connolly, 1952- Poetsch, Susan Patricia, 1966- Walsh, Michael James, 1948- Dewey Number: 499.15 Cover image: ‘Wiradjuri Water Symbols 1’, drawing by Lynette Riley. Water symbols represent a foundation requirement for all to be sustainable in their environment. -

PRG 1686 Series List Page 1 of 4 Sister Michele Madiga

_________________________________________________________________________ Sister Michele Madigan PRG 1686 Series List _________________________________________________________________________ Subject files relating to the campaign against the proposed radioactive 1 dump in South Australia. 1998-2004. 21.5 cm. Comprises subject files compiled by Michele Madigan: File 1: Environmentalists’ information and handouts File 2: Environmentalists’ information and handouts File 3: Greenpeace submission re radioactive wastes disposal File 4: Kupa Piti Kungka Tjuta (Coober Pedy Senior Aboriginal Women’s Council) campaign against radioactive dump papers File 5: Kupa Piti Kungka Tjuta – press clippings File 6: Coober Pedy town group campaign against a radioactive dump File 7: Postcards and printed material File 8: Michele Madigan’s personal correspondence against a radioactive dump File 9: SA Parliamentary proceedings against a radioactive dump File 10: Federal Government for a radioactive dump. File 11: Press cuttings. File 12: Brochures, blank petition forms and information, produced by various groups (Australian Conservation Foundation, Friends of the Earth, etc. Subject files relating to uranium mining (mainly in S.A.) 2 1996-2011. 10 cm. Comprises seven files which includes brochures, press clippings, emails, reports and newsletters. File 1 : Roxby Downs – Western Mining (WMC) / Olympic Dam File 2: Ardbunna elder, Kevin Buzzacott. File 3: Beverley and Honeymoon mines in South Australia. File 4: Background to uranium mining in Australia. File 5: Proposed expansion of Olympic Dam. File 6: Transportation of radioactive waste including across South Australia. File 7: Northern Territory traditional owners against Mukaty Dump proposal. PRG 1686 Series list Page 1 of 4 _________________________________________________________________________ Subject files relating to the British nuclear explosions at Maralinga 3 in the 1950s and 1960s. -

Coober Pedy Regional Times

Outback Community Newspaper Est 1982 ISSN 1833-1831 •Mechanic on duty •Tyres •Tyre repairs •Fuel •Parts •Opening hours 7.30am- 5pm Tel: 08 86725 920 http://cooberpedyregionaltimes.wordpress.com Thursday 10 October 2013 ANANGU ELDERS WANT STATE GOVERNMENT INVESTIGATED “$3 million dollars in member’s funds has gone missing and the AARD [Aboriginal Affairs and Reconciliation Division] have been asleep at the wheel”, said APY Lands Traditional Elder Mr. George Kenmore. “We have sought the assistance of the South Australian Ombudsman to investigate serious issues that have been reported to us. We are looking forward to his findings at the end of this month.” “We would not be in this predicament if our land was worthless. Put simply the government wants us off our land so that they can source the minerals. That's the plain truth and they have been doing everything in their power to force their way in. Tribal Elders travelled to Adelaide recently to report to a Standing Committee on the state of affairs on the APY Lands, particularly with regard to lack of consultation by the Minister for Aboriginal Affairs Mr. Ian Hunter. The Anangu wanted changes made to the way the APY Lands board was structured and they wanted their consitution changed however before the Ombudsman has delivered his findings, the Minister for Aboriginal Affairs is trying to engage us with a review of the APY Lands Act, that they had not wanted altered. The APY Lands Council of Elders including Mr. George Kenmore who A news release from Premier and Cabinet on Tuesday, reads: travelled to Adelaide to give evidence at a Parliamentary Standing Committee on the ‘state of the nation’ on the APY Lands Community consultation has begun for a review of South Australia’s landmark Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara (APY) Land Rights Act. -

For the Ultimate Remote Touring Destination, You Can't Go Past The

TRAVEL Gibson Desert, WA For the ultimate remote touring destination, you can’t go past the Gibson Desert QUENCHING A WORDS AND PHOTOGRAPHY BY LINDA BLOFFWITCH DESERT38 THIRST 39 TRAVEL Gibson Desert, WA hen you mention to someone servicing and spares, but out here you need a lot ■ WHERE: that you’re planning a trip to more than what can just be purchased over the The Gibson Desert is located in remote THE ICONIC LEN BEADELL MADE the desert, you can pretty well counter. You’ll be amazed that little things like central Western Australia. Travelling Wguarantee the Simpson Desert spinifex seeds and not protecting your shockers the Great Central Road, access is via will generally come to mind. But in fact, the can cause such huge issues on a trip like this. Warburton (560km from Yulara and REMOTE TRAVEL POSSIBLE IN THIS Simpson couldn’t be any further from where Before heading off, we spent considerable 560km from Laverton). From Alice we were heading. This trip was going to be time calculating our food and water for our Springs, travel the Gary Junction Road absolutely epic, as it would take us smack bang remote six weeks adventure, building in several before turning onto the Gary Highway. PART OF THE COUNTRY to the middle of central Western Australia, to the days extra for any emergencies. Finalising the remote Gibson Desert. trip itinerary took ages, and fuel was always ■ INFORMATION: Travelling the Gibson would unquestionably going to be a concern when it’s a killer for Travelling to the Gibson Desert How’s this for a magnificent relic… you don’t get to see a Mk 5 Jaguar be one of the most remote regions in weight. -

DESERT ADVENTURE Words and Images: Emma George

desert AN EXTRAORDINARY DESERT ADVENTURE Words and images: Emma George here are road trips and then there are giving travellers distances to nearest towns and extraordinary experiences! Tackling roads. Some of these markers we found, many the West Australian desert with three others had been souvenired unfortunately. young kids may sound crazy, but The markers became our challenge so Texploring the Gary Junction Road and Karlamilyi we’d know exactly what to look for. One was (Rudall River) National Park is something we the milestone of the North Territory and Western were really excited about. Australian border – finally back in our home state We’d been on the road for months, of WA, but more remote than ever and not a car conquering Cape York, the Gulf and Arnhem to be seen all day. Land, but my husband, Ashley, and I, with We rolled out our map of Australia on the our three young boys in tow wanted one last red dirt in the middle of the road showing the adventure before heading home to Perth. kids exactly where we were, where we’d been Deserts are dangerous places, so months and where we were going. Our next stop was were spent planning this trip, making sure to refuel at Kiwirrkurra, a small Aboriginal town we had enough food and water for five days, and one of the most remote communities in permits, spares, and repair kits for the car and the world. camper as well as safety procedures, a satellite phone, EPIRB, accessible fire extinguisher, first aid and a nightly call-home regime. -

Dislocating the Frontier Essaying the Mystique of the Outback

Dislocating the frontier Essaying the mystique of the outback Dislocating the frontier Essaying the mystique of the outback Edited by Deborah Bird Rose and Richard Davis Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] Web: http://epress.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Dislocating the frontier : essaying the mystique of the outback. Includes index ISBN 1 920942 36 X ISBN 1 920942 37 8 (online) 1. Frontier and pioneer life - Australia. 2. Australia - Historiography. 3. Australia - History - Philosophy. I. Rose, Deborah Bird. II. Davis, Richard, 1965- . 994.0072 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Indexed by Barry Howarth. Cover design by Brendon McKinley with a photograph by Jeff Carter, ‘Dismounted, Saxby Roundup’, http://nla.gov.au/nla.pic-vn3108448, National Library of Australia. Reproduced by kind permission of the photographer. This edition © 2005 ANU E Press Table of Contents I. Preface, Introduction and Historical Overview ......................................... 1 Preface: Deborah Bird Rose and Richard Davis .................................... iii 1. Introduction: transforming the frontier in contemporary Australia: Richard Davis .................................................................................... 7 2. -

Larry Wells and the Lost Tribe

LARRY WELLS AND THE LOST TRIBE Geoffrey SANDFORD, Australia Key words : Larry Wells, lost tribe SUMMARY In 1981 the author and friend sought to locate an explorers mark in the Great Victoria Desert of outback South Australia. This mark was a blaze in a kurrajong tree made by surveyor Larry Wells as part of the Elder Scientific Expedition of 1891. The blazed tree has been described as surely one the most remote explorers marks in the world. However during the attempt to find the explorers mark the adventure took an unusual turn after the discovery of an aboriginal artefact on a sand-hill. On planning a second expedition to the same area in May1986 the author joked so often that he was going to find “the lost tribe” that he actually believed he would. In October of that year a last nomadic tribe of seven aboriginals walked out of the Great Victoria Desert. Successive harsh years made their old way of living now impossible and they surrendered to white “civilisation”. The tribal leader had deliberately steered his people away from white society for their entire lives. In contrast the Elder Scientific Expedition of 1891 encountered totally different conditions in the Great Victoria Desert even experiencing rain, mists and fog for much of their journey. Even with those freak events they just managed to reach Victoria Springs with their camels nearly dead. History has not been kind to either to either the nomadic aboriginals or Larry Wells. The nomads failed to adapt to their new confinement and they struggled to survive. -

Template Over Metropolitan Adelaide

LARRY WELLS AND THE LOST TRIBE Geoffrey SANDFORD, Australia Key words: Larry Wells, lost tribe SUMMARY In 1981 the author and friend sought to locate an explorers mark in the Great Victoria Desert of outback South Australia. This mark was a blaze in a kurrajong tree made by surveyor Larry Wells as part of the Elder Scientific Expedition of 1891. The blazed tree has been described as surely one the most remote explorers marks in the world. However during the attempt to find the explorers mark the adventure took an unusual turn after the discovery of an aboriginal artefact on a sand-hill. On planning a second expedition to the same area in May1986 the author joked so often that he was going to find “the lost tribe” that he actually believed he would. In October of that year a last nomadic tribe of seven aboriginals walked out of the Great Victoria Desert. Successive harsh years made their old way of living now impossible and they surrendered to white “civilisation”. The tribal leader had deliberately steered his people away from white society for their entire lives. In contrast the Elder Scientific Expedition of 1891 encountered totally different conditions in the Great Victoria Desert even experiencing rain, mists and fog for much of their journey. Even with those freak events they just managed to reach Victoria Springs with their camels nearly dead. History has not been kind to either to either the nomadic aboriginals or Larry Wells. The nomads failed to adapt to their new confinement and they struggled to survive. -

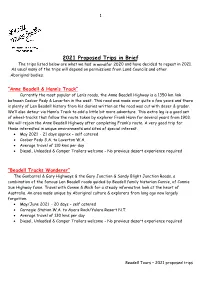

202 Proposed Trips in Brief

1 2021 Proposed Trips in Brief The trips listed below are what we had in mind for 2020 As usual many of the trips will depend on permissions from Land Counc ils and other Aboriginal bodies. “Anne Beadell & Hann’s Track” Currently the most popular of Len’s roads, the Anne Beadell Highway is a 1350 km link between Coober Pedy & Laverton in the west. This road was made over quite a few years and there is plenty of Len Beadell history from his diaries written as the road was cut with dozer & grader. We’ll also detour via Hann’s Track to add a little bit more adventure. This extra leg is a good set of wheel-tracks that follow the route taken by explorer Frank Hann for several years from 1903. We will rejoin the Anne Beadell Highway after completing Frank’s route. A very good trip for those interested in unique environments and sites of special interest. • May 2021 - 21 days approx – self catered • Coober Pedy S.A. to Laverton W.A. • Average travel of 110 kms per day • Diesel, Unleaded & Camper Trailers welcome - No previous desert experience required “Beadell Tracks Wanderer” The Gunbarrel & Gary Highways & the Gary Junction & Sandy Blight Junction Roads, a combination of the famous Len Beadell roads guided by Beadell family historian Connie, of Connie Sue Highway fame. Travel with Connie & Mick for a steady informative look at the heart of Australia. An area made unique by Aboriginal culture & explorers from long ago now largely forgotten. • May/June 2021 - 20 days – self catered • Carnegie Station W.A. -

Retracing the Tracks of Len Beadell

MEDIA RELEASE May 6, 2011 RETRACING THE TRACKS OF LEN BEADELL Leading tag-along-tour operators, Global Gypsies, will soon embark on another new and exciting 4WD expedition, this time a discovery tour to retrace the tracks of legendary outback figure, Len Beadell. A talented surveyor, road builder, bushman, artist and author, Beadell is often called “the last true Australian explorer". He was responsible for opening up over 2.5 million square kilometers of the last remaining isolated desert areas of central Australia in the 1940’s and 1950’s and his books are mandatory reading for modern day adventurers. There is also a fascinating museum dedicated to him at Giles Weather Station on the Great Central Road. To read more about Len Beadell, visit the website run by his daughter at www.beadell.com.au . On this exciting escorted and catered 14-day, self-drive 'discovery' tour, the Gypsies will retrace for the first time the historic dirt tracks which Len created to make the outback more accessible. A small convoy of 4WD’s will be led by an expert guide communicating by two-way radio – independent but not alone. They will begin the challenging journey in the goldfields hub of Kalgoorlie, head east towards the Great Victoria Desert and Laverton, take the Anne Beadell Highway to Neal Junction, travel north on the Connie Sue Highway to Warburton, tackle the Gun Barrel Highway through to Carnegie Station and conclude the expedition in the remote town of Wiluna. Eco-accredited former Tour Guide of the Year and qualified mechanic, Jeremy Perks, will lead the expedition.