Stories from the River

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WALKING TOUR of SAN ANTONIO To

Girl Scouts of Southwest Texas GSSWT Council's Own Patch Program 300 Tri-Centennial - WALKING TOUR OF SAN ANTONIO To earn this patch, you must visit 10 places of interest (5 of those underlined plus 5 others). Begin your walking tour by visiting the VISITORS INFORMATION CENTER, 317 ALAMO PLAZA 78205, (210) 207-6700. The order in which the sites are listed is a suggested route. THE ALAMO (visit the Long Barrack while there and see a 15 minute movie) Cross Alamo Plaza and walk down THE RIVER by Hyatt Regency Hotel (123 Losoya St. 78205) RIVER CENTER MALL Take the SIGHTSEEING RIVERBOAT (tour lasts about 40 minutes) 9:00 a.m. to 10:20 p.m. Call (210) 244-5700 for current prices and information. * OR * Walk along THE RIVER to the ARNESON RIVER THEATER LA VILLITA (see plaques on the outside wall of La Villita Assembly Hall) Down to MAIN PLAZA... COURTHOUSE CITY HALL on MILITARY PLAZA SAN FERNANDO CATHEDRAL SPANISH GOVERNOR'S PALACE NAVARRO HOUSE EL MERCADO (Market Square, 512 W. Commerce St. 78206) (210) 299-1330 Catch the VIA STREET CAR (Trolley Bus) and return to ALAMO PLAZA and EAST COMMERCE STREET Walk to HEMISFAIR PLAZA Tour THE INSTITUTE OF TEXAS CULTURES TOWER OF THE AMERICAS (see page 3 for more information) *PRICES AND INFORAMTION SUBJECT TO CHANGE* We strongly recommend contacting the sites for updates on prices and conditions. *See page 3 for more information about tour sites. PLAZA DE MEXICO - MEXICAN CULTURAL INSTITUTE THE FAIRMOUNT HOTEL DOWNTOWN PLAYGROUND (Hemisfair Park) Additional Downtown Attractions: PLAZA THEATER OF WAX and RIPLEY'S BELIEVE IT OR NOT (301 Alamo Plaza, across from the Alamo) 9:00 a.m. -

Neil Fauerso, Altered States Catalogue Ruiz-Healy, 2018

HILLS SNYDER Altered States Altered November 2018 - January 2019 Contemporary Art from Latin America & Texas Hills Snyder Altered States November 2018- January 2019 Ruiz-Healy Art 201 East Olmos Drive San Antonio, Texas 78212 (210) 804 2219 ruizhealyart.com Ruiz-Healy Art 201 A East Olmos Drive San Antonio, Texas 78212 210.804.2219 Editor and Introduction Author Patricia Ruiz-Healy, Ph.D Essay Author Neil Fauerso Director of Sales, NY Patti Ruiz-Healy Gallery Manager Deliasofia Zacarias Design Cynthia Prado Photography Ansen Seale This publication was issued to accompany the exhibition Hills Snyder Altered States organized by Ruiz-Healy Art. On view from November 2018 to January 2019 Front cover: Opportunity, MT 01, 2016 Back cover: Opportunity, MT 02, 2016 Last Page: Happy, TX 7, 2016 Copyright © 2018 Ruiz-Healy Art Elk Creek Road, WY, 2016 Hills Snyder: Altered States Ruiz-Healy Art is pleased to present its first solo-exhibition for the work of Hills Snyder, Altered States (Part Four), an ongoing visual project and written series by the Texas-based artist. The exhibit features one hundred and twenty drawings, based on photographs gathered in Oklahoma, Texas, Colorado, Wyoming, Montana, Utah, Nevada, California, New Mexico, Kansas and South Dakota. As stated by Snyder, his travels follow a line that “goes through towns selected by virtue of their names—not because they are odd or funny, but because they are evocative—emotional states, hoped for ideals, downers, and reckonings…” Nowhere, Happy, Bonanza, Lost Springs, Recluse, Keystone, Opportunity, Diamondville, Eden, Eureka, Bummerville, Nothing, Truth or Consequences, Eldorado and Waterloo are among the places visited by the artist. -

Your Kids Are Going to Love

10 Places In San Antonio Your Kids Are Going to Love www.chicagotitlesa.com 1. Brackenridge Park This sprawling park has way more than just green space — it encompasses a stretch of the San Antonio River and includes the Japanese Tea Garden, the Sunken Garden Theater, the San Antonio Zoo as well as ball fields and pavilions. Older kids can run off some energy on nearby trails while parents eat a family picnic. Before you leave, don’t miss a ride on the San Antonio Zoo Eagle, a miniature train that loops around pretty much the entire park. From its starting point right across from the zoo, it makes stops at a few different Brackenridge attractions, including the Witte Museum. 2. The DoSeum Since opening in 2015, The DoSeum has quickly become the go-to children’s museum in San Anto- nio — it’s full of hands-on activities for kids of all ages, from toddlers to fifth graders — though adults will admittedly learn a thing or two as well. The museum’s displays run the gamut, from celebrating creative arts to tinkering with science and technology. Specific exhibits include the Big Outdoors, the Sensations Studio (where kids can experiment with light and sound), an innovation station, and the Spy Academy. 3. Six Flags Fiesta Texas Families looking for an adrenaline fix while still spending time together should hit up Six Flags Fiesta Texas. Not only does the park have some of the best roller coasters in Texas, including the Superman Krypton Virtual Reality Coaster, Iron Rattler, and Batman: The Ride (the world’s first 4D free-fly coaster, which just might be as terrifying as it sounds), but it has rides and attractions for the whole family, regardless of age, energy levels, and attention spans. -

THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 14, 2013 Grand Hyatt Hotel San Antonio, Texas

THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 14, 2013 Grand Hyatt Hotel San Antonio, Texas THE PRIDE OF TEXAS BUSINESS WELCOME Mark M. Johnson Chairman, Texas Business Hall of Fame Edward E. Whitacre, Jr. Master of Ceremonies RECOGNITION OF TEXAS BUSINESS HALL OF FAME MEMBERS RECOGNITION OF 2013 INDUCTEES INVOCATION Reverend Trey H. Little DINNER RECOGNITION OF 2013 SCHOLARSHIP RECIPIENTS HALL OF FAME INDUCTION CEREMONY CLOSING REMARKS Mark M. Johnson Jordan Cowman Chairman, 2014, Texas Business Hall of Fame 2013 Inductees to the Texas Business Hall of Fame Charlie Amato Joseph M. “Jody” Grant Chairman/Co-Founder Chairman Emeritus and Texas Capital Bancshares, Inc. Gary Dudley Dallas President/Co-Founder SWBC H-E-B San Antonio Represented by Craig Boyan President, COO Tom Dobson San Antonio Chairman Whataburger Rex W. Tillerson San Antonio Chairman and CEO Exxon Mobil Corporation Paul Foster Irving Executive Chairman Western Refining, Inc. El Paso Charlie Amato & Gary Dudley Chairman/Co-Founder & President/Co-Founder SWBC | San Antonio Charlie Amato and Gary Dudley, Co-founders of SWBC, have had a long friendship. Through this friendship, they established SWBC, a company with more than three decades of dedication to not just great business and customer service, but also giving back to their community. Amato and Dudley met in grade school and were reunited in their college years. Both men graduated from Sam Houston State University with Bachelors of Business Administration degrees. After graduation they went their separate ways. Dudley became a coach and worked in the Houston school district for nine months before he was drafted into the armed forces. He spent six months on active duty with the US Marines (and six years as a reservist) before returning to coaching for another year. -

Original TMDL

Upper San Antonio River Watershed Protection Plan SSaa nn AAnnttoonniioo RRiivveerr AAuutthhoorriittyy BBeexxaarr RReeggiioonnaall WWaatteerrsshheedd MMaannaaggeemmeenntt PPaarrttnneerrsshhiipp TTeexxaass CCoommmmiissssiioonn oonn EEnnvviirroonnmmeennttaall QQuuaalliittyy James Miertschin & Associates, Inc. Parsons, Inc. JAMES MIERTSCHIN & ASSOCIATES, INC. ENVIRONMENTAL ENGINEERING P.O. BOX 162305 • AUSTIN, TEXAS 78716-2305 • (512) 327-2708 UPPER SAN ANTONIO RIVER WATERSHED PROTECTION PLAN Prepared For: San Antonio River Authority 100 East Guenther Street San Antonio, Texas 78204 and Bexar Regional Watershed Management Partnership Prepared in Cooperation With: Texas Commission on Environmental Quality The preparation of this report was financed through grants from the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality. Prepared By: James Miertschin & Associates, Inc. Parsons, Inc. December 2006 The Seal appearing on this document was authorized by Dr. James D. Miertschin, P.E. 43900 on 14 Dec 2006. TABLE OF CONTENTS Section Page LIST OF TABLES...............................................................................................................v LIST OF FIGURES ........................................................................................................... vi LIST OF ABREVIATIONS ............................................................................................. vii I. WPP SUMMARY...........................................................................................................1 1.0 INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................1 -

Stormwater Management Program 2013-2018 Appendix A

Appendix A 2012 Texas Integrated Report - Texas 303(d) List (Category 5) 2012 Texas Integrated Report - Texas 303(d) List (Category 5) As required under Sections 303(d) and 304(a) of the federal Clean Water Act, this list identifies the water bodies in or bordering Texas for which effluent limitations are not stringent enough to implement water quality standards, and for which the associated pollutants are suitable for measurement by maximum daily load. In addition, the TCEQ also develops a schedule identifying Total Maximum Daily Loads (TMDLs) that will be initiated in the next two years for priority impaired waters. Issuance of permits to discharge into 303(d)-listed water bodies is described in the TCEQ regulatory guidance document Procedures to Implement the Texas Surface Water Quality Standards (January 2003, RG-194). Impairments are limited to the geographic area described by the Assessment Unit and identified with a six or seven-digit AU_ID. A TMDL for each impaired parameter will be developed to allocate pollutant loads from contributing sources that affect the parameter of concern in each Assessment Unit. The TMDL will be identified and counted using a six or seven-digit AU_ID. Water Quality permits that are issued before a TMDL is approved will not increase pollutant loading that would contribute to the impairment identified for the Assessment Unit. Explanation of Column Headings SegID and Name: The unique identifier (SegID), segment name, and location of the water body. The SegID may be one of two types of numbers. The first type is a classified segment number (4 digits, e.g., 0218), as defined in Appendix A of the Texas Surface Water Quality Standards (TSWQS). -

The Historical Narrative of San Pedro Creek by Maria Watson Pfeiffer and David Haynes

The Historical Narrative of San Pedro Creek By Maria Watson Pfeiffer and David Haynes [Note: The images reproduced in this internal report are all in the public domain, but the originals remain the intellectual property of their respective owners. None may be reproduced in any way using any media without the specific written permission of the owner. The authors of this report will be happy to help facilitate acquiring such permission.] Native Americans living along San Pedro Creek and the San Antonio River 10,000 years ago were sustained by the swiftly flowing waterways that nourished a rich array of vegetation and wildlife. This virtual oasis in an arid landscape became a stopping place for Spanish expeditions that explored the area in the 17th and early 18th centuries. It was here that Governor Domingo Terán de los Ríos, accompanied by soldiers and priests, camped under cottonwood, oak, and mulberry trees in June 1691. Because it was the feast of Saint Anthony de Padua, they named the place San Antonio.1 In April 1709 an expedition led by Captain Pedro de Aguirre, including Franciscan missionaries Fray Isidro Félix de Espinosa and Fray Antonio Buenventura Olivares, visited here on the way to East Texas to determine the possibility of establishing new missions there. On April 13 Espinosa, the expedition’s diarist, wrote about a lush valley with a plentiful spring. “We named it Agua de San Pedro.” Nearby was a large Indian settlement and a dense growth of pecan, cottonwood, cedar elm, and mulberry trees. Espinosa recorded, “The river, which is formed by this spring, could supply not only a village, but a city, which could easily be founded here.”2 When Captain Domingo Ramón visited the area in 1716, he also recommended that a settlement be established here, and within two years Viceroy Marqués de Valero directed Governor Don Martín de Alarcón to found a town on the river. -

San Antonio San Antonio, Texas

What’s ® The Cultural Landscape Foundation ™ Out There connecting people to places tclf.org San Antonio San Antonio, Texas Welcome to What’s Out There San Antonio, San Pedro Springs Park, among the oldest public parks in organized by The Cultural Landscape Foundation the country, and the works of Dionicio Rodriguez, prolificfaux (TCLF) in collaboration with the City of San Antonio bois sculptor, further illuminate the city’s unique landscape legacy. Historic districts such as La Villita and King William Parks & Recreation and a committee of local speak to San Antonio’s immigrant past, while the East Side experts, with generous support from national and Cemeteries and Ellis Alley Enclave highlight its significant local partners. African American heritage. This guidebook provides photographs and details of 36 This guidebook is a complement to TCLF’s digital What’s Out examples of the city's incredible landscape legacy. Its There San Antonio Guide (tclf.org/san-antonio), an interactive publication is timed to coincide with the celebration of San online platform that includes the enclosed essays plus many Antonio's Tricentennial and with What’s Out There Weekend others, as well as overarching narratives, maps, historic San Antonio, November 10-11, 2018, a weekend of free, photographs, and biographical profiles. The guide is one of expert-led tours. several online compendia of urban landscapes, dovetailing with TCLF’s web-based What’s Out There, the nation’s most From the establishment of the San Antonio missions in the comprehensive searchable database of historic designed st eighteenth century, to the 21 -century Mission and Museum landscapes. -

MEXICO Las Moras Seco Creek K Er LAVACA MEDINA US HWY 77 Springs Uvalde LEGEND Medina River

Cedar Creek Reservoir NAVARRO HENDERSON HILL BOSQUE BROWN ERATH 281 RUNNELS COLEMAN Y ANDERSON S HW COMANCHE U MIDLAND GLASSCOCK STERLING COKE Colorado River 3 7 7 HAMILTON LIMESTONE 2 Y 16 Y W FREESTONE US HW W THE HIDDEN HEART OF TEXAS H H S S U Y 87 U Waco Lake Waco McLENNAN San Angelo San Angelo Lake Concho River MILLS O.H. Ivie Reservoir UPTON Colorado River Horseshoe Park at San Felipe Springs. Popular swimming hole providing relief from hot Texas summers. REAGAN CONCHO U S HW Photo courtesy of Gregg Eckhardt. Y 183 Twin Buttes McCULLOCH CORYELL L IRION Reservoir 190 am US HWY LAMPASAS US HWY 87 pasas R FALLS US HWY 377 Belton U S HW TOM GREEN Lake B Y 67 Brady iver razos R iver LEON Temple ROBERTSON Lampasas Stillhouse BELL SAN SABA Hollow Lake Salado MILAM MADISON San Saba River Nava BURNET US HWY 183 US HWY 190 Salado sota River Lake TX HWY 71 TX HWY 29 MASON Buchanan N. San G Springs abriel Couple enjoying the historic mill at Barton Springs in 1902. R Mason Burnet iver Photo courtesy of Center for American History, University of Texas. SCHLEICHER MENARD Y 29 TX HW WILLIAMSON BRAZOS US HWY 83 377 Llano S. S an PECOS Gabriel R US HWY iver Georgetown US HWY 163 Llano River Longhorn Cavern Y 79 Sonora LLANO Inner Space Caverns US HW Eckert James River Bat Cave US HWY 95 Lake Lyndon Lake Caverns B. Johnson Junction Travis CROCKETT of Sonora BURLESON 281 GILLESPIE BLANCO Y KIMBLE W TRAVIS SUTTON H GRIMES TERRELL S U US HWY 290 US HWY 16 US HWY P Austin edernales R Fredericksburg Barton Springs 21 LEE Somerville Lake AUSTIN Pecos -

San Antonio, Texas

L<>$VJ£ 3 J? itSStxi* 'A ^OUvEfjii^ "of TH^ |d V ;U>a V_i\ UA &AN ANTON a tt r^-si+. * r For Your Home Entertainment COLUMBIA GRAPHOPHONES EDISON PHONOGRAPHS ¥ * VICTOR TALKING MACHINES t f "We Have em All. Also The Largest Selection of Records for all Machines in the City. Souvenirs of San Antonio Post Cards, Books, Stationery, Cigars, Tobaccos and Pipes. The most complete line of Daily Papers and Magazines (from all parts of the world) in the city. WE TAKE SUBSCRIPTIONS FOR ANYTHING IN PRINT, Louis Book Store, <TWO STORES) fgtl^g; ft 3 1 -4* SOUVENIR up The Picturesque Alamo City SAN ANTONIO, TEXAS PRESENTED TO THE VISITORS TO SAN ANTONIO 1907 Through the Courtesy of the San Antonio Traction Com pans N. B.—The publishers of this book take pleasure in recommending the advertisers whose cards appear herein as thoroughly reliable in all respects, and it is due to their liberal patronage that the publishers are able to distribute these books free to patrons of the Observation Cars. i-rn-no a nirmTv* n «»• i EBERS & WUR1 Z, Publishers, SAN ANTONIO. TEXAS. "We were not here to assist in the defense of the Alamo, but we are here as factors to build up and develop 'The Alamo City' and the\Great Southwest." Investment in Real Estate net from 7 to 15% interest. Residences—Anything from a cottage to a palace. Building Sites on the Heights or down town, close in, from $300 per lot up. Acreage in the suburbs from $30 to $100 per acre. -

NWS Instruction 10-605, Tropical Cyclone Official Geographic Defining Points, Dated March 17, 2020

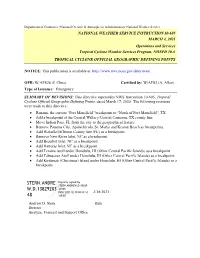

Department of Commerce •National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration •National Weather Service NATIONAL WEATHER SERVICE INSTRUCTION 10-605 MARCH 4, 2021 Operations and Services Tropical Cyclone Weather Services Program, NWSPD 10-6 TROPICAL CYCLONE OFFICIAL GEOGRAPHIC DEFINING POINTS NOTICE: This publication is available at: http://www.nws.noaa.gov/directives/. OPR: W/AFS26 (J. Cline) Certified by: W/AFS2 (A. Allen) Type of Issuance: Emergency SUMMARY OF REVISIONS: This directive supersedes NWS Instruction 10-605, Tropical Cyclone Official Geographic Defining Points, dated March 17, 2020. The following revisions were made to this directive: • Rename the current “Port Mansfield” breakpoint to “North of Port Mansfield”, TX. • Add a breakpoint at the Coastal Willacy/Coastal Cameron, TX county line. • Move Indian Pass, FL from the city to the geographical feature. • Remove Panama City, Apalachicola, St. Marks and Keaton Beach as breakpoints. • Add Wakulla/Jefferson County line (FL) as a breakpoint. • Remove New River Inlet, NC as a breakpoint. • Add Beaufort Inlet, NC as a breakpoint. • Add Hatteras Inlet, NC as a breakpoint. • Add Teraina Atoll under Honolulu, HI (Other Central Pacific Islands) as a breakpoint • Add Tabuaeran Atoll under Honolulu, HI (Other Central Pacific Islands) as a breakpoint • Add Kiritimati (Christmas) Island under Honolulu, HI (Other Central Pacific Islands) as a breakpoint Digitally signed by STERN.ANDRE STERN.ANDREW.D.13829 W.D.13829203 20348 Date: 2021.02.18 08:45:54 2/18/2021 48 -05'00' Andrew D. Stern Date Director Analyze, Forecast and Support Office NWSI 10-605 MARCH 4, 2021 OFFICIAL DEFINING POINTS FOR TROPICAL CYCLONE WATCHES AND WARNINGS *An asterisk following a breakpoint indicates the use of the breakpoint includes land areas adjacent to the body of water. -

Native American Languages, Indigenous Languages of the Native Peoples of North, Middle, and South America

Native American Languages, indigenous languages of the native peoples of North, Middle, and South America. The precise number of languages originally spoken cannot be known, since many disappeared before they were documented. In North America, around 300 distinct, mutually unintelligible languages were spoken when Europeans arrived. Of those, 187 survive today, but few will continue far into the 21st century, since children are no longer learning the vast majority of these. In Middle America (Mexico and Central America) about 300 languages have been identified, of which about 140 are still spoken. South American languages have been the least studied. Around 1500 languages are known to have been spoken, but only about 350 are still in use. These, too are disappearing rapidly. Classification A major task facing scholars of Native American languages is their classification into language families. (A language family consists of all languages that have evolved from a single ancestral language, as English, German, French, Russian, Greek, Armenian, Hindi, and others have all evolved from Proto-Indo-European.) Because of the vast number of languages spoken in the Americas, and the gaps in our information about many of them, the task of classifying these languages is a challenging one. In 1891, Major John Wesley Powell proposed that the languages of North America constituted 58 independent families, mainly on the basis of superficial vocabulary resemblances. At the same time Daniel Brinton posited 80 families for South America. These two schemes form the basis of subsequent classifications. In 1929 Edward Sapir tentatively proposed grouping these families into superstocks, 6 in North America and 15 in Middle America.