Irish Music Abroad

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Car Designer Porsche, 76, Dies

Time: 04-05-2012 23:05 User: ccathcart PubDate: 04-06-2012 Zone: IN Edition: 1 Page Name: B4 Color: CyanMagentaYellowBlack B4 | FRIDAY,APRIL 6, 2012 | THE COURIER-JOURNAL INDIANA &DEATHS | courier-journal.com IN Car designer Porsche, 76, dies Came up with four-cylinder.It’sacombi- day.” nation that the company Porsche was the son of 911sportscar has evolved instead of re- former Porsche Chairman placing and which turns on Ferry Porsche, who died in By David McHugh car enthusiasts even today. 1998, and the grandson of Associated Press The 911, now in its sev- Ferdinand Porsche, who enth version, remains rec- started the company as a FRANKFURT, Germany — ognizably the same vehi- design and engineering The Porsche 911, with its cle, though with much up- firm in the 1930s. sloping roof line, long hood dated mechanical parts Born in Stuttgart on and powerful rear engine, and technology. Dec. 11,1935, F.A. Porsche has been asports car-lov- The new car was origi- was initiated into the fam- er’sfantasy for the half- nally designated the 901, ily business while still a century since its1963 intro- but the number was boy,spending time in his duction. Its creator,Ferdi- changed because French grandfather’sworkshops nand Alexander Porsche, competitor Peugeot and design facilities. He 76, grandson of the auto- claimed apatent on car studied at the Ulm School maker’sfounder,has died. names formed with azero of Design and joined the Porsche died Thursday in the middle. company in 1958, taking in Salzburg, Austria, Manny Alban, president over the design studio in Porsche AG said. -

Biocultural Diversity and Indigenous Ways of Knowing: Human Ecology in the Arctic

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Science Science Research & Publications 2009 Biocultural Diversity and Indigenous Ways of Knowing: Human Ecology in the Arctic Kassam, Karim-Aly University of Calgary Press Kassam, Karim-Aly. 2009. Biocultural Diversity and Indigenous Ways of Knowing: Human Ecology in the Arctic. Calgary: University of Calgary Press. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/47782 book Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca University of Calgary Press www.uofcpress.com BIOCULTURAL DIVERSITY AND INDIGENOUS WAYS OF KNOWING: KARIM-ALY S. KASSAM HUMAN ECOLOGY IN THE ARCTIC by Karim-Aly S. Kassam ISBN 978-1-55238-566-1 THIS BOOK IS AN OPEN ACCESS E-BOOK. It is an electronic version of a book that can be purchased in physical form through any bookseller or on-line retailer, or from our distributors. Please support this open access publication by requesting that your university purchase a print copy of this book, or by purchasing a copy yourself. If you have any questions, please contact us at BIOCULTURAL DIVERSITY AND INDIGENOUS [email protected] WAYS OF KNOWING HUMAN ECOLOGY IN THE ARCTIC Cover Art: The artwork on the cover of this book is not open access and falls under traditional copyright provisions; it cannot be reproduced in any way without written permission of the artists and their agents. The cover can be displayed as a complete cover image for the purposes of publicizing this work, but the artwork cannot be extracted from the context of the cover of this specific work without breaching the artist’s copyright. -

“Whiskey in the Jar”: History and Transformation of a Classic Irish Song Masters Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment Of

“Whiskey in the Jar”: History and Transformation of a Classic Irish Song Masters Thesis Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Dana DeVlieger, B.A., M.A. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2016 Thesis Committee: Graeme M. Boone, Advisor Johanna Devaney Anna Gawboy Copyright by Dana Lauren DeVlieger 2016 Abstract “Whiskey in the Jar” is a traditional Irish song that is performed by musicians from many different musical genres. However, because there are influential recordings of the song performed in different styles, from folk to punk to metal, one begins to wonder what the role of the song’s Irish heritage is and whether or not it retains a sense of Irish identity in different iterations. The current project examines a corpus of 398 recordings of “Whiskey in the Jar” by artists from all over the world. By analyzing acoustic markers of Irishness, for example an Irish accent, as well as markers of other musical traditions, this study aims explores the different ways that the song has been performed and discusses the possible presence of an “Irish feel” on recordings that do not sound overtly Irish. ii Dedication Dedicated to my grandfather, Edward Blake, for instilling in our family a love of Irish music and a pride in our heritage iii Acknowledgments I would like to thank my advisor, Graeme Boone, for showing great and enthusiasm for this project and for offering advice and support throughout the process. I would also like to thank Johanna Devaney and Anna Gawboy for their valuable insight and ideas for future directions and ways to improve. -

When Art Becomes Political: an Analysis of Irish Republican Murals 1981 to 2011

Providence College DigitalCommons@Providence History & Classics Undergraduate Theses History & Classics 12-15-2018 When Art Becomes Political: An Analysis of Irish Republican Murals 1981 to 2011 Maura Wester Providence College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.providence.edu/history_undergrad_theses Part of the Cultural History Commons, and the European History Commons Wester, Maura, "When Art Becomes Political: An Analysis of Irish Republican Murals 1981 to 2011" (2018). History & Classics Undergraduate Theses. 6. https://digitalcommons.providence.edu/history_undergrad_theses/6 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the History & Classics at DigitalCommons@Providence. It has been accepted for inclusion in History & Classics Undergraduate Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Providence. For more information, please contact [email protected]. When Art Becomes Political: An Analysis of Irish Republican Murals 1981 to 2011 by Maura Wester HIS 490 History Honors Thesis Department of History and Classics Providence College Fall 2018 For my Mom and Dad, who encouraged a love of history and showed me what it means to be Irish-American. CONTENTS INTRODUCTION …………………………………………………………………… 1 Outbreak of The Troubles, First Murals CHAPTER ONE …………………………………………………………………….. 11 1981-1989: The Hunger Strike, Republican Growth and Resilience CHAPTER TWO ……………………………………………………………………. 24 1990-1998: Peace Process and Good Friday Agreement CHAPTER THREE ………………………………………………………………… 38 The 2000s/2010s: Murals Post-Peace Agreement CONCLUSION……………………………………………………………………… 59 BIBLIOGRAPHY …………………………………………………………………… 63 iv 1 INTRODUCTION For nearly thirty years in the late twentieth century, sectarian violence between Irish Catholics and Ulster Protestants plagued Northern Ireland. Referred to as “the Troubles,” the violence officially lasted from 1969, when British troops were deployed to the region, until 1998, when the peace agreement, the Good Friday Agreement, was signed. -

ANTH 233 Ethnographic Studies Tuesdays 12:45-2:00Pm & Thursdays, 11:15Am-12:30Pm, NH 156 Winter 2017

ANTH 233 Ethnographic Studies Tuesdays 12:45-2:00pm & Thursdays, 11:15am-12:30pm, NH 156 Winter 2017 Instructor: Dr. Christina Holmes Office: Bruce Brown 335G, Tel: 867-5853, E-mail: [email protected] Office Hours: Monday 10:30-11:30am, 1-2pm, Tuesday 10am-12noon; Wednesday 1-2 pm; Thursday 1-2pm; Other times by appointment Course Content: This course explores the rich cultural diversity of human societies around the globe through an ethnographic lens. Using a variety of ethnographic works, students will analyse how anthropologists have represented this diversity. Course material will include classic and current texts about ‘other’ and ‘own’ societies, the representation of Indigenous peoples, ethnographic film, as well as portrayals of culture in popular media. Evaluation: Midterm Examination: 20% Final Examination: 30% Book Club Assignments & Ethnography Review Blog 40% Participation Assignments 10% _________________________________________________________________________________ Total: 100% Moodle site: Go to the StFX Moodle Login Page at https://moodle.stfx.ca/login/index.php . Log in using your StFX username and password. Click on the Anth 112.22 link to access our Moodle site. We will use Moodle throughout this course, so make sure you can connect. If you have problems, talk to me or to TSG. All detailed assignment instructions, weekly reading quizzes, course powerpoints and other features will be on Moodle! Exams: will include a mixture of multiple choice questions, short answer questions, and short essay questions. Assignments: Participation assignments (10%): This will be made up from exercises done in class (13 in total, 1/week), which may include one minute essays, concept maps, mini-assignments, etc. -

Interview Mit John Sheahan 2002 (Hans-Jürgen Fink, Hamburger Abendblatt)

Interview mit John Sheahan 2002 (Hans-Jürgen Fink, Hamburger Abendblatt) ? Was für eine Situation war das damals in Irland, als die Dubliners in den 60er- Jahren ihre Karriere starteten? Welche Bedeutung hatte das Singen und Musizieren, und welche Marktlücke haben Sie damals erobert? ! 1962 – das war eine völlig andere Welt, sie hat sich viel langsamer bewegt – heute ist alles so hektisch und verrückt. Die Leute hatten mehr Zeit, Zeit zum Nachdenken. Und die irische Musik, das war die Welt der älteren Generation. Sie war nicht schrecklich populär unter jüngeren Leuten und hat diese Generation erst langsam wieder erobert. Bei mir war das etwas anders, ich habe Tin Whistle gelernt und dann Flöte; ich bin ja wie Barney MacKenna in einer musikalischen Familie aufgewachsen. Die Art der „Dubliners“, mit der traditionellen irischen Musik umzugehen, war neu und erfrischend, sie brachte eine ganz andere Vitalität hinein. Nur ein Beispiel: Die älteren Musiker, das waren meist Dance Bands, sie haben alle gesessen. Wir standen auf der Bühne, wir haben gespielt und gesungen, und wir haben uns bewegt. Die Leute schienen das zu mögen, und so haben wir uns unsere ganz eigene Nische im Markt geschaffen. Wir haben die Leute magisch zur irischen Musik hingezogen, der wir neues Leben eingehaucht hatten. ? Sie sind jetzt vierzig Jahre im Musikgeschäft – das ist einzigartig. Wie würden Sie denn Ihr Erfolgsrezept beschreiben? ! Vermutlich ist es unser Erfolgsrezept, dass wir nie irgendeins gehabt haben. Wir haben ja noch nicht mal Verträge untereinander. Wir spielen einfach, wir haben musikalisch viel anzubieten, jeder bringt seine Soli ein. Und noch etwas ist ganz wichtig: Wir hängen nicht zwischen unseren Tourneen zusammen. -

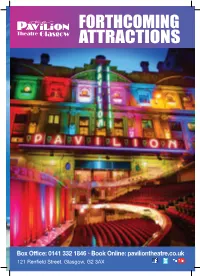

Forthcoming Attractions

This Year's Fabulous Family Panto FORTHCOMING ATTRACTIONS Additional Star studded cast to be announced soon! Box Office: 0141 332 1846 • Book Online: paviliontheatre.co.uk 121 Renfield Street, Glasgow, G2 3AX Thank you for requesting this brochure. You will see that the early part of this year has a lower than usual number of shows. This, unfortunately, is the ongoing consequences of last year’s fire in Sauchiehall Street where a number of promoters unfortunately placed their shows at other venues due to the uncertainty of when we would reopen. We are confident that the autumn period and beyond will see us back to the usual number of shows and hope you can bear with us at this time until things get back to normal. Thank you for your ongoing support and we hope to see you at some of our future shows. Jimeoin Friday 8th February - 7:30pm All Seats: £18.50 An evening of world class stand-up as the Irishman from Australia brings his brilliantly observed, ever-evolving and hilarious comedy. Don’t miss your chance to see this award-winning star of TV shows including ‘Live at the Apollo’, ‘Royal Variety Performance’, ‘John Bishop Show’, CH4’s O2 Gala’ and ‘Sunday Night at the Palladium’ – Live! Age Restriction: 14+ Nish Kumar – It’s In Your Nature To Destroy Yourselves Saturday 9th February - 7:30pm All seats £22.50 Double Edinburgh Comedy Award Nominee! The title is a quote from Terminator 2. There will be jokes about politics, mankind’s capacity for self- destruction and whether it will lead to the end of days. -

146.101 Introductory Social Anthropology Paper Number

146.101 Introductory Social Anthropology Paper Number: 146.101. Paper Title: Introductory Social Anthropology. Credits Value: 15 credits. Calendar Prescription: Social Anthropology, a foundation discipline in the social sciences, seeks to explain and understand cultural and social diversity. This course introduces students to key contemporary topics in the discipline, including the practice of field research, politics and power, systems of healing, mythology and ritual, urbanisation and globalisation, kinship and family. Pre and co requisites: Prerequisites: None. Corequisites: None. Semester: Semester 1. Campus: Manawatu Mode: Distance Learning E-Learning Category: Required Paper Coordinator: TBA Paper Controller: Dr. Robyn Andrews School of People, Environment and Planning Phone: (06) 356 9099 ext 2490 Email: [email protected] Timetable: The timetable for lectures, laboratories, and tutorials can be found at http://publictimetable.massey.ac.nz/ Learning outcomes: As a result of completing this course satisfactorily students will gain: • An understanding of the conceptual vocabulary, methodology, history, and the range of study in social anthropology Prepared by: 146101 1101_PNTH_E.docx Page 1 of 3 Last Updated: 28/7/10 School of People, Environment and Planning • The ability to critique ethnographic texts • An understanding of the viability and persistence of a great diversity of socio/cultural adaptations • The ability to apply a cross-cultural perspective to a wide range of contemporary issues Major topics: The concept of culture The concept of society Anthropological methods Myth and ritual Kinship, marriage and the family Dimensions of inequality Anthropology and colonialism Ethnicity and Race Assessment proportions: Internal Assessment 70% Final Examination 30% Description of assessment activities: Essay and Short Answer - 30% Research Project - 40% Examination - 30% Due Dates / Deadlines: The due dates for assignments (and any other internal assessment components) will be advised at the start of the semester. -

Les Actes De Colloques Du Musée Du Quai Branly Jacques Chirac

Les actes de colloques du musée du quai Branly Jacques Chirac 2 | 2009 Performance, art et anthropologie Observation and Context Chris Wright Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/actesbranly/434 DOI: 10.4000/actesbranly.434 ISSN: 2105-2735 Publisher Musée du quai Branly Jacques Chirac Electronic reference Chris Wright, « Observation and Context », Les actes de colloques du musée du quai Branly Jacques Chirac [Online], 2 | 2009, Online since 27 November 2009, connection on 08 September 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/actesbranly/434 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/actesbranly.434 This text was automatically generated on 8 September 2020. © Tous droits réservés Observation and Context 1 Observation and Context Chris Wright 1 That was the opening, or very close to the opening, 10 minutes of Cameron Jamie’s film 2002 Kranky Klaus. Usually the film is screened with a lively accompaniment. So the music you hear in the background is from a band called The Melvins. Usually The Melvins are playing life and the image is even bigger. The sound is obviously much more important. Cameron Jamie comes from a fine art background; a painting background and he his now working as an anthropologist. Cameron Jamie’s work is particularly interesting for me, partly because it deals with performance, such as here. In the year 2000 Cameron Jamie started the “goat project” for which he dressed up in various costumes, goes back to his home town of Northridge in the Santa Anna valley in California. He might dress up like a kind of Dracula and then going to supermarket buying something, and this one witness gives a kind of testimonial to a professional illustrator who then makes a drawing, based on this testimonial account. -

Dublin City Honours Music Legend Luke Kelly

22 January 2019 Dublin City Honours Music Legend Luke Kelly One of the most famous sons of Dublin, music legend and activist Luke Kelly will be honoured by his beloved Dublin City, friends and family in celebration of his life, with the unveiling of two individual Luke Kelly statues, one on either side of the city, on 30th January 2019 to mark the 35th anniversary of his death. Organised by Dublin City Council, the official unveiling of both sculptures will be undertaken by President of Ireland Michael D Higgins, in the presence of the Lord Mayor of Dublin, Nial Ring. From the streets of north Dublin to stages all over the world, Luke Kelly built his career on his ability to connect with the Irish people through story and song. Luke’s impact on the Dublin and Irish music scene revival of the 60s/70s is immense and inspiring a new generation since his death, his voice is as relevant today as it was 50 years ago. Speaking on behalf of organisers Dublin City Council, the Lord Mayor of Dublin, Nial Ring said “Luke’s presence is still felt on the streets of his birthplace Sheriff St and the pubs and haunts of the literati circles around Grafton St/Baggot St where he frequented. This is a unique celebration for a very unique man. To this day he inspires Irish and international artists through his words, songs and activism. It is only fitting that we celebrate the man, the music and his immeasurable impact on the Irish music scene and wider Irish culture. -

Loving the Art in Yourself

Technological University Dublin ARROW@TU Dublin Books/Book Chapters Conservatory of Music and Drama 2014 Loving the Art in Yourself Mary Moynihan Technological University Dublin, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/aaconmusbk Part of the Acting Commons, Music Commons, and the Other Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Moynihan, M. (2014) Loving the Art in Yourself. In S. Burch & B. McAvera (eds.) Stanislavski in Ireland- Focus at 50,(pp.4-25) Dublin, Carysfort Press. This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the Conservatory of Music and Drama at ARROW@TU Dublin. It has been accepted for inclusion in Books/Book Chapters by an authorized administrator of ARROW@TU Dublin. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 License 2 I Loving the art in yourself Mary Moynihan After spending five years in New York, training and performing with theatre practitioners such as 'Erwin Piscator, Saul Colin, Lee Strasberg and Allan Miller", American-born Deirdre O'Connell (1939-2001) came to Ireland and founded the Stanislavski Acting Studio of Dublin in May 1963. The Stanislavski studio was so named as the type of training that Deirdre wanted to bring to Ireland. It was based on the theatrical theoh and techniques of the Russian Theatre practitioner, actor and director Konstantin Stanislavski (1863-1938), founder and theatre administrator ofthe Moscow Art Theatre and creator ofthe Stanislavski system of actor training, 'the most influential system of acting in the Western World'.2 The Stanislavski approach is a system of training, not a specific style of acting, that aims to provide the skills necessary for the actor to develop the inner life; the emotional and sensory life of the character. -

Endangered African Languages Featured in a Digital Collection: the Case of the ǂkhomani San | Hugh Brody Collection

Proceedings of the First workshop on Resources for African Indigenous Languages (RAIL), pages 1–8 Language Resources and Evaluation Conference (LREC 2020), Marseille, 11–16 May 2020 c European Language Resources Association (ELRA), licensed under CC-BY-NC Endangered African Languages Featured in a Digital Collection: The Case of the ǂKhomani San | Hugh Brody Collection Kerry Jones, Sanjin Muftic Director, African Tongue, Linguistics Consultancy, Cape Town, South Africa Postdoctoral Research Fellow, English Language and Linguistics, Rhodes University, Makhanda, South Africa Research Associate, Department of General Linguistics, Stellenbosch University, Stellenbosch, South Africa; Digital Scholarship Specialist, Digital Library Services, University of Cape Town, South Africa [email protected], [email protected] Abstract The ǂKhomani San | Hugh Brody Collection features the voices and history of indigenous hunter gatherer descendants in three endangered languages namely, N|uu, Kora and Khoekhoe as well as a regional dialect of Afrikaans. A large component of this collection is audio-visual (legacy media) recordings of interviews conducted with members of the community by Hugh Brody and his colleagues between 1997 and 2012, referring as far back as the 1800s. The Digital Library Services team at the University of Cape Town aim to showcase the collection digitally on the UCT-wide Digital Collections platform, Ibali which runs on Omeka-S. In this paper we highlight the importance of such a collection in the context of South Africa, and the ethical steps that were taken to ensure the respect of the ǂKhomani San as their stories get uploaded onto a repository and become accessible to all. We will also feature some of the completed collection on Ibali and guide the reader through the organisation of the collection on the Omeka-S backend.