Medical Humanities: an E-Module at the University of Manchester

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Feature Films

NOMINATIONS AND AWARDS IN OTHER CATEGORIES FOR FOREIGN LANGUAGE (NON-ENGLISH) FEATURE FILMS [Updated thru 88th Awards (2/16)] [* indicates win] [FLF = Foreign Language Film category] NOTE: This document compiles statistics for foreign language (non-English) feature films (including documentaries) with nominations and awards in categories other than Foreign Language Film. A film's eligibility for and/or nomination in the Foreign Language Film category is not required for inclusion here. Award Category Noms Awards Actor – Leading Role ......................... 9 ........................... 1 Actress – Leading Role .................... 17 ........................... 2 Actress – Supporting Role .................. 1 ........................... 0 Animated Feature Film ....................... 8 ........................... 0 Art Direction .................................... 19 ........................... 3 Cinematography ............................... 19 ........................... 4 Costume Design ............................... 28 ........................... 6 Directing ........................................... 28 ........................... 0 Documentary (Feature) ..................... 30 ........................... 2 Film Editing ........................................ 7 ........................... 1 Makeup ............................................... 9 ........................... 3 Music – Scoring ............................... 16 ........................... 4 Music – Song ...................................... 6 .......................... -

A Film by DENYS ARCAND Produced by DENISE ROBERT DANIEL LOUIS

ÉRIC MÉLANIE MELANIE MARIE-JOSÉE BRUNEAU THIERRY MERKOSKY CROZE AN EYE FOR BEAUTY A film by DENYS ARCAND Produced by DENISE ROBERT DANIEL LOUIS before An Eye for Beauty written and directed by Denys Arcand producers DENISE ROBERT DANIEL LOUIS THEATRICAL RELEASE May 2014 synopsis We spoke of those times, painful and lamented, when passion is the joy and martyrdom of youth. - Chateaubriand, Memoirs from Beyond the Tomb Luc, a talented young architect, lives a peaceful life with his wife Stephanie in the stunning area of Charlevoix. Beautiful house, pretty wife, dinner with friends, golf, tennis, hunting... a perfect life, one might say! One day, he accepts to be a member of an architectural Jury in Toronto. There, he meets Lindsay, a mysterious woman who will turn his life upside down. AN EYE FOR BEAUTY | PRESS KIT cast Luc Éric Bruneau Stéphanie Mélanie Thierry Lindsay Melanie Merkosky Isabelle Marie-Josée Croze Nicolas Mathieu Quesnel Roger Michel Forget Mélissa Geneviève Boivin-Roussy Karine Magalie Lépine-Blondeau Museum Director Yves Jacques Juana Juana Acosta Élise Johanne-Marie Tremblay 3 AN EYE FOR BEAUTY | PRESS KIT crew Director Denys Arcand Producers Denise Robert Daniel Louis Screenwriter Denys Arcand Director of Photography Nathalie Moliavko-Visotzky Production Designer Patrice Bengle Costumes Marie-Chantale Vaillancourt Editor Isabelle Dedieu Music Pierre-Philippe Côté Sound Creation Marie-Claude Gagné Sound Mario Auclair Simon Brien Louis Gignac 1st Assistant Director Anne Sirois Production manager Michelle Quinn Post-Production Manager Pierre Thériault Canadian Distribution Les Films Séville AN EYE FOR BEAUTY | PRESS KIT 4 SCREENWRITER / DIRECTOR DENYS ARCAND An Academy Award winning director, Denys Arcand's films have won over 100 prestigious awards around the world. -

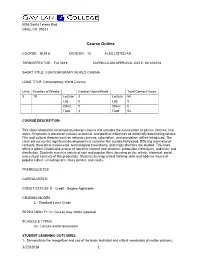

Course Outline 3/23/2018 1

5055 Santa Teresa Blvd Gilroy, CA 95023 Course Outline COURSE: HUM 6 DIVISION: 10 ALSO LISTED AS: TERM EFFECTIVE: Fall 2018 CURRICULUM APPROVAL DATE: 03/12/2018 SHORT TITLE: CONTEMPORARY WORLD CINEMA LONG TITLE: Contemporary World Cinema Units Number of Weeks Contact Hours/Week Total Contact Hours 3 18 Lecture: 3 Lecture: 54 Lab: 0 Lab: 0 Other: 0 Other: 0 Total: 3 Total: 54 COURSE DESCRIPTION: This class introduces contemporary foreign cinema and includes the examination of genres, themes, and styles. Emphasis is placed on cultural, economic, and political influences as artistically determining factors. Film and cultural theories such as national cinemas, colonialism, and orientalism will be introduced. The class will survey the significant developments in narrative film outside Hollywood. Differing international contexts, theoretical movements, technological innovations, and major directors are studied. The class offers a global, historical overview of narrative content and structure, production techniques, audience, and distribution. Students screen a variety of rare and popular films, focusing on the artistic, historical, social, and cultural contexts of film production. Students develop critical thinking skills and address issues of popular culture, including race, class gender, and equity. PREREQUISITES: COREQUISITES: CREDIT STATUS: D - Credit - Degree Applicable GRADING MODES L - Standard Letter Grade REPEATABILITY: N - Course may not be repeated SCHEDULE TYPES: 02 - Lecture and/or discussion STUDENT LEARNING OUTCOMES: 1. Demonstrate the recognition and use of the basic technical and critical vocabulary of motion pictures. 3/23/2018 1 Measure of assessment: Written paper, written exams. Year assessed, or planned year of assessment: 2013 2. Identify the major theories of film interpretation. -

Reference Guide This List Is for Your Reference Only

REFERENCE GUIDE THIS LIST IS FOR YOUR REFERENCE ONLY. WE CANNOT PROVIDE DVDs OF THESE FILMS, AS THEY ARE NOT PART OF OUR OFFICIAL PROGRAMME. HOWEVER, WE HOPE YOU’LL EXPLORE THESE PAGES AND CHECK THEM OUT ON YOUR OWN. DRAMA ACT OF THE HEART BLACKBIRD 1970 / Director-Writer: Paul Almond / 103 min / 2012 / Director-Writer: Jason Buxton / 103 min / English / PG English / 14A A deeply religious woman’s piety is tested when a Sean (Connor Jessup), a socially isolated and bullied teenage charismatic Augustinian monk becomes the guest conductor goth, is falsely accused of plotting a school shooting and in her church choir. Starring Geneviève Bujold and Donald struggles against a justice system that is stacked against him. Sutherland. BLACK COP ADORATION ADORATION 2017 / Director-Writer: Cory Bowles / 91 min / English / 14A 2008 / Director-Writer: Atom Egoyan / 100 min / English / 14A A black police officer is pushed to the edge, taking his For his French assignment, a high school student weaves frustrations out on the privileged community he’s sworn to his family history into a news story involving terrorism and protect. The film won 10 awards at film festivals around the invites an Internet audience in on the resulting controversy. world, and the John Dunning Discovery Award at the CSAs. With Scott Speedman, Arsinée Khanjian and Rachel Blanchard. CAST NO SHADOW 2014 / Director: Christian Sparkes / Writer: Joel Thomas ANGELIQUE’S ISLE Hynes / 85 min / English / PG 2018 / Directors: Michelle Derosier (Anishinaabe), Marie- In rural Newfoundland, 13-year-old Jude Traynor (Percy BEEBA BOYS Hélène Cousineau / Writer: James R. -

Past Film Screenings

Inaugural film: Margaret’s Museum, May 1996 Season 1 1996/1997 Season 5 2000/2001 Antonia’s Line, Sept 1996 East is East, Sept 2000 Lone Star, Oct 1996 New Waterford Girl, Oct 2000 Long Day’s Journey into Night, Nov 1996 Saving Grace, Nov 2000 Big Night, Dec 1996 Stardom, Nov 2000 Celestial Clockwork, Jan 1997 Waydowntown, Jan 2001 Secrets and Lies, Feb 1997 Chocolat, Feb 2001 Breaking the Waves, Mar 1997 Goya in Bordeaux, Mar 2001 Hotel de Love, Apr 1997 Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, Apr 2001 Waiting for Guffman, May 1997 The Widow of St. Pierre, Apr 2001 Season 2 1997/1998 Season 6 2001/2002 Ulee’s Gold, Sept 1997 The Dish, Sept 2001 When The Cat’s Away, Oct 1997 The Closet, October 2001 Fire, Nov 1997 The Golden Bowl, Nov 2001 Shall We Dance, Dec 1997 The Uncles, Nov 2001 The Hanging Garden, Jan 1998 Innocence, Jan 2002 The Sweet Hereafter, Feb 1998 The War Bride, Feb 2002 The Full Monty, Mar 1998 Kandahar, Mar 2002 Ice Storm, Apr 1998 Amelie, Apr 2002 Mrs. Dalloway, May 1998 Bread and Tulips, Apr 2002 Season 3 1998/1999 Gala Opening of the new Galaxy, July 2002 The Governess, Sept 1998 Amelie Smoke Signals, Oct 1998 The Importance of being Earnest Last Night, Nov 1998 Iris The Red Violin, Dec 1998 Atanarjuat Jerry and Tom, Jan 1999 Men in Black II Life is Beautiful, Feb 1999 Elizabeth, Mar 1999 Season 7 2002/2003 Nõ, Apr 1999 Atanarjuat, Sept 2002 Little Voice, May 1999 Baran, Oct 2002 Bollywood/Hollywood, Nov 2002 Season 4 1999/2000 Nuit de Noces, Dec 2002 This Is My Father, Sept 1999 Mostly Martha, Jan 2003 Besieged, Oct 1999 8 Femmes, Jan 2003 Earth, Nov 1999 Rabbit Proof Fence, Mar 2003 Felicia's Journey, Jan 2000 The Pianist, Apr 2003 Happy, Texas, Feb 2000 The Russian Ark, May 2003 XIU-XIU: The Sent Down Girl, Mar 2000 All About My Mother, Apr 2000 Straight Story, Apr 2000 Owen Sound’s Reel Festival 1, Feb 2003 Season 10 2005/2006 Marion Bridge Ladies in Lavender, Sept 2005 Bowling for Columbine Sabah, Oct 2005 Frida Brothers, Oct 2005 Standing in the Shadows of Motown Mad Hot Ballroom, Nov 2005 Far from Heaven Water, Jan 2006 Mrs. -

Following Is a Listing of Public Relations Firms Who Have Represented Films at Previous Sundance Film Festivals

Following is a listing of public relations firms who have represented films at previous Sundance Film Festivals. This is just a sample of the firms that can help promote your film and is a good guide to start your search for representation. 11th Street Lot 11th Street Lot Marketing & PR offers strategic marketing and publicity services to independent films at every stage of release, from festival premiere to digital distribution, including traditional publicity (film reviews, regional and trade coverage, interviews and features); digital marketing (social media, email marketing, etc); and creative, custom audience-building initiatives. Contact: Lisa Trifone P: 646.926-4012 E: [email protected] www.11thstreetlot.com 42West 42West is a US entertainment public relations and consulting firm. A full service bi-coastal agency, 42West handles film release campaigns, awards campaigns, online marketing and publicity, strategic communications, personal publicity, and integrated promotions and marketing. With a presence at Sundance, Cannes, Toronto, Venice, Tribeca, SXSW, New York and Los Angeles film festivals, 42West plays a key role in supporting the sales of acquisition titles as well as launching a film through a festival publicity campaign. Past Sundance Films the company has represented include Joanna Hogg’s THE SOUVENIR (winner of World Cinema Grand Jury Prize: Dramatic), Lee Cronin’s THE HOLE IN THE GROUND, Paul Dano’s WILDLIFE, Sara Colangelo’s THE KINDERGARTEN TEACHER (winner of Director in U.S. competition), Maggie Bett’s NOVITIATE -

Revista Médicas UIS Vol.26 No.3 2013.Indd

médicas uis revista de los estudiantes de medicina de la universidad industrial de santander Editorial The Role of Cinema and Television in People’s Perception of Medicine and Healthcare-related Topics Adriana Marcela Arenas-Rojas* *Estudiante VIII Nivel de Medicina. Editora Asociada y Miembro del Consejo Editorial de la Revista MÉDICAS UIS. Facultad de Salud. Universidad Industrial de Santander. Bucaramanga. Santander. Colombia. Correspondencia: Srita. Adriana Marcela Arenas-Rojas. Apto 130, Bloque 14-20B, Bucarica IV Etapa. Floridablanca. Santander. Colombia. Correo electrónico: [email protected] “Although for some people cinema means something When it comes to television, though it may seem that superficial and glamorous, it is something else. I think the medical dramas have only been recently popular, it is the mirror of the world.” in fact they have been around for years. The success of Ben Casey in the 1960s and M.A.S.H. and Marcus Jeanne Moreau Welby, M.D. in the 1970s represented a defining period on the history of television’s prime-time medical series. Since their inception, cinema and television have This set a path for a whole new genre in television that unquestionably transformed the way contemporary was quickly followed by L.A. Law, St. Elsewhere, and society views itself. The screen is a broad canvas Doogie Howser, M.D. in the 1980s; E.R. and Chicago on which settings and characters come to life Hope in the 1990s; and most recently Grey’s Anatomy reflecting the changes culture has gone through and House M.D. in the 2000s5-7. over the years. -

1 the Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project TERESA CHIN JONES Interviewed By

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project TERESA CHIN JONES Interviewed by: Charles Stuart Kennedy Initial interview date: July 2, 2007 Copyright 2007 ADS TABLE OF CONTENTS Background Born in the SSR of Chinese diplomatic parents. Raised in SSR and S. Parents Life in Tashkent Communist take-over of China Settling in New )ersey niversity of Pennsylvania Religion Chinese history and folklore Nixon opening to China Marriage niversity of Pennsylvania, Chemistry Program Student 19.9-1960 Reasons for choosing Penn Fellow classmates Ph.D1 1966 2ietnam 3ar Agriculture Department Laboratories 1966-1968 3yndmoor Agricultural Research Labs. 3ashington1 D.C. Dairy Lab. Chromatography Paris1 France, Institute Pasteur7 Post Doctorate 1969-1981 3ife of Foreign Service Officer David )ones Birth of twins 2ineland1 New )ersey, Substitute Mathematics Teacher 1981-1982 Dealing with problem pupils Entered the Foreign Service in 1984 1984 1 3ashington1 DC, Arms Control and Disarmament Agency 1984-1986 2erification technology issues Binary chemical weapons Chemical1 Biological1 Radiological (CBR) 3arfare Three Mile Island Misconception of nuclear reactor vulnerability Destroying a nuclear reactor Iraq?s Osirak reactor India?s Peaceful Nuclear Explosion Intra-Agency bickering Soviet technology Leave without pay 1986-1988 Accompanied husband to NATO Ambassador Strausz-HupA Brussels1 Belgium, Consular Officer 1988-1980 FlemingC3aloon relationship 2isa cases Environment Holzman Amendment Congressional interest Iran -

Course Catalog 10-11

Course Catalog 2010-11 L U APPLETON, WISCONSIN CONTENTS About Lawrence ............................................................................................................. 7 Mission.................................................................................................................. 7 Educational philosophy ......................................................................................... 7 Lawrence in the community .................................................................................. 7 History................................................................................................................... 8 Presidents of the college..................................................................................... 10 A Liberal Arts Education.............................................................................................. 11 Liberal learning ................................................................................................... 11 A Lawrence education ........................................................................................ 12 A residential education........................................................................................ 12 The Campus Community ............................................................................................. 13 Academic and campus life services.................................................................... 13 The campus and campus life ............................................................................. -

PDF of the Cinelation “Incendies” Review

Film Reviews by Christopher Beaubien “Incendies” Review By Christopher Beaubien • January 28, 2011 The Elegance and Dread of an Equation Nawal Marwan is dead. She is sur- INCENDIES vived by her twin children Jeanne Directed by Denis Villeneuve Screenplay by Denis Villeneuve and Simon, both in their late twen- Adapted from the play “Scorched” ties and living in Montreal. They sit by Wadji Mouawad before the notary Jean Lebel (Rémy Script Consultant: Girard) who had employed Nawal Valérie Beaugrand-Champagne Original Music by Grégoire Hetzel (Lubna Azabal) as his secretary for Director of Photography: André Turpin years. He has always considered Edited by Monique Dartonne them all to be a part of his family. Production Designer: The room is still and unbearably André-Line Beauparlant Produced by Luc Déry and Kim McCraw quiet. As he reads Nawal’s final Released by Sony Pictures Classics will and testament aloud, Jeanne Running time: 130 minutes (Mélissa Désormeaux-Poulin) and Si- Aspect Ratio: 1.85:1 mon (Maxim Gaudette) are disturbed Country: Canada | France Canada: 14A by their mother’s final request. She USA (MPAA): Rated R for some strong wants to be buried naked facing the violence and language. ground without a headstone to iden- tify her. Where did this self-loath- CAST Lubna Azabal: Nawal Marwan ing come from? Jeanne keeps her Mélissa Désormeaux-Poulin: composure and listens. Simon goes Jeanne Marwan berserk over how cold and insane Maxim Gaudette: Simon Marwan their mother was. He will not respect Rémy Girard: Notary Jean Lebel Abdelghafour Elaaziz: Abou Tarek her wishes. Allen Altman: Notary Maddad Mohamed Majd: Chamseddine Professionally bound to secrecy Nabil Sawalha: Fahim about Nawal’s mysterious past, Jean Baya Belal: Maika emphasizes how grave this situation is: “Childhood is a knife stuck in the back of your throat. -

2018-2019 Undergraduate Catalog

2018/2019 EASTERN UNIVERSITY UNDERGRADUATE PROGRAMS Undergraduate 2018/2019 Catalog An Innovative Christian University with Undergraduate, Graduate, Professional, Urban, International, and Seminary Programs www.eastern.edu Eastern University Is An Equal Opportunity University Eastern University is committed to providing Equal Educational and Employment Opportunity to all qualified persons regardless of their economic or social status and does not discriminate in any of its policies, programs, or activities on the basis of sex, age, race, handicap, marital or parental status, color, or national or ethnic origin. Regulation Change The University reserves the right to change its regulations, courses of study, and schedule of fees without previous notice. Copyright ©2018 Eastern University 2018/2019 Undergraduate Programs TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION n Introduction to Eastern ....................................................................................................... 1 n Welcome and Mission Statement ....................................................................................... 2 n Accreditation and Memberships ........................................................................................ 5 n History .................................................................................................................................... 6 n Doctrinal Statement ............................................................................................................. 7 ADMISSION n Admission of Traditional Baccalaureate -

5. David Hanley – Conceptualizing Quebec Cinema

Conceptualizing Quebec National Cinema: Denys Arcand’s Cycle of Post-Referendum Films as Case Study By David Hanley ver the past half century, Quebec cinema has grown from small beginnings into an industry that regularly produces feature films that win critical Orecognition and festival prizes around the globe. At the same time, it is one of the few places in the world where local products can occasionally outdraw Hollywood blockbusters at the box office. This essay analyzes the Quebec film industry, examines what types of films it produces and for what audiences, and explores the different ways domestic and international audiences understand its films. The pioneer figure in introducing Quebec cinema to mainstream audiences beyond the province is writer- director Denys Arcand. His cycle of films dealing with the failure of his generation to achieve independence for Quebec offers both a paradigm of a type of film newly important to the Quebec industry, and a case study in explaining how and why certain films cross borders into foreign markets. Of particular interest in this essay are Arcand’s Le déclin de l’empire américain (1986), Jésus de Montréal (1989) and Les invasions barbares (2003), all of which had successful commercial releases in international markets, including the United States, a rare occurrence for a Quebec film. One reason this international popularity is of interest is that the films’ politics, central to their narratives, were and are controversial in Quebec. However, this political aspect is largely invisible to non-Quebec audiences, who appreciate the films for their other qualities, a tendency that can be seen in a handful of recent Quebec films that have also received international commercial distribution.