Ethnography in a Highly Sensitive Setting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 14 Water Supply Sector Programme 14.1 Objectives for Water Supply Sector Development

13-203 13-203 The Study on the Comprehensive Urban Development Plan for Greater Kumasi in the Republic of Ghana Final Report Table of Contents Volume 2 Page PART VI Infrastructure Sector Plans and Programmes for Greater Kumasi Sub-Region Chapter 12 Transport Sector Plan and Programme 12.1 Objectives for Transportation Sector Development ................................................... 12-1 12.1.1 Objectives for Transportation Sector Development ...................................................12-1 12.1.2 Policy for Transportation Sector Development ..........................................................12-1 12.2 Future Transport Demand Analysis............................................................................ 12-4 12.3 Strategies for Transportation Sector Development..................................................... 12-8 12.3.1 Improvement of Road Network Function...................................................................12-8 12.3.2 Improvement for Intersection and Signalization Improvement..................................12-8 12.3.3 Enhancement of Public Transport Development........................................................12-9 12.3.4 Introduction of Traffic Control in CBD......................................................................12-9 12.3.5 Introduction of Transportation Demand Management ...............................................12-9 12.3.6 Development of Freight Transport Management......................................................12-10 12.4 Transportation Sector Plan ...................................................................................... -

Middle Belt Zone

Beneficiary Communities 10-Seater Water Closet Community-based Mechanized 1,000 metric tonnes Institutional Toilets with Solar Powered Water System prefabricated grains No. Constituency Mechanized Boreholes warehouses 1. Biemso No. 1 RC Sch. 1. Pokukrom 2. Adugyama Jubilee sch. 2. Abesewa Ahafo-Ano South East 3. Sabronum RC Prim. 3. Nsutem 1. Mankranso DA Primary 1. Mpasaso No.2 2. Wioso DA Prim. Sch 2. Bonkwaso No.1 Ahafo-Ano South West 3. Domeabra RC Prim. 3. Asokore Newtown 1. Anyinasusu Community 1. Bredi Tepa (Odikro Nkwanta) 2. Tepa Zongo 2. Numasua Ahafo-Ano North 3. Akwasiase 3. Subriso 1. Odumasi Adum Afrancho 1. Chichibon 2. Twedie 2. Twedie Atwima Kwanwoma, 3. Trede 3. Bebu 1. Tano Dumase SHS 1. Tanodumase 2. Mpasatia STHS 2. Mpasatia Atwima Mponua, 3. Achiase JHS 3. Apenimadi 1. Atwima Akropong 1. Boahenkwaa 2. Atwima Adankwame 2. Worapong Atwima Nwabiagya North, 3. Barekese 3. Ataase 1. Agogo Primary 1. Gyankobaa 2. Amadum Adankwame Prim 2. Nkoran Atwima Nyabiahya South 3. Nkwawie Panin Anglican Prim 3. Kobeng 1. Nyaboe 1. Odumase NT 2. Obinimase 2. Konongo Abosomtweaga Asante Akim Central, 3. Dwease 3. Patriensa 1. Juansa 1. Pekyerekye 2. Hwediem 2. Juansa Asante Akim North, 3. Domeabra 3. Kansaso 1. Joaso funeral grounds 1. Ofoase SHS 2. Bompata market 2. Dansereso Asante Akim South, 3. Obogu 3. Bompata SHS 1. Drobonso 1. Anyinofi Drobonso 2. Fumsua 2. Fumsua Sekyere Afram Plains 3. Anyinofi 3. Samso 1. Akwasiso 1. Adubia 2. Manso Kaniago 2. Agroyesum Manso Adubia, 3. Manso Mem 3. Dome Beposo 1 Beneficiary Communities 10-Seater Water Closet Community-based Mechanized 1,000 metric tonnes Institutional Toilets with Solar Powered Water System prefabricated grains No. -

Electoral Commission of Ghana List of Registered Voters - 2006

Electoral Commission of Ghana List of Registered voters - 2006 Region: ASHANTI District: ADANSI NORTH Constituency ADANSI ASOKWA Electoral Area Station Code Polling Station Name Total Voters BODWESANGO WEST 1 F021501 J S S BODWESANGO 314 2 F021502 S D A PRIM SCH BODWESANGO 456 770 BODWESANGO EAST 1 F021601 METH CHURCH BODWESANGO NO. 1 468 2 F021602 METH CHURCH BODWESANGO NO. 2 406 874 PIPIISO 1 F021701 L/A PRIM SCHOOL PIPIISO 937 2 F021702 L/A PRIM SCH AGYENKWASO 269 1,206 ABOABO 1 F021801A L/A PRIM SCH ABOABO NO2 (A) 664 2 F021801B L/A PRIM SCH ABOABO NO2 (B) 667 3 F021802 L/A PRIM SCH ABOABO NO1 350 4 F021803 L/A PRIM SCH NKONSA 664 5 F021804 L/A PRIM SCH NYANKOMASU 292 2,637 SAPONSO 1 F021901 L/A PRIM SCH SAPONSO 248 2 F021902 L/A PRIM SCH MEM 375 623 NSOKOTE 1 F022001 L/A PRIM ARY SCH NSOKOTE 812 2 F022002 L/A PRIM SCH ANOMABO 464 1,276 ASOKWA 1 F022101 L/A J S S '3' ASOKWA 224 2 F022102 L/A J S S '1' ASOKWA 281 3 F022103 L/A J S S '2' ASOKWA 232 4 F022104 L/A PRIM SCH ASOKWA (1) 464 5 F022105 L/A PRIM SCH ASOKWA (2) 373 1,574 BROFOYEDRU EAST 1 F022201 J S S BROFOYEDRU 352 2 F022202 J S S BROFOYEDRU 217 3 F022203 L/A PRIM BROFOYEDRU 150 4 F022204 L/A PRIM SCH OLD ATATAM 241 960 BROFOYEDRU WEST 1 F022301 UNITED J S S 1 BROFOYEDRU 130 2 F022302 UNITED J S S (2) BROFOYEDRU 150 3 F022303 UNITED J S S (3) BROFOYEDRU 289 569 16 January 2008 Page 1 of 144 Electoral Commission of Ghana List of Registered voters - 2006 Region: ASHANTI District: ADANSI NORTH Constituency ADANSI ASOKWA Electoral Area Station Code Polling Station Name Total Voters -

District Analytical Report, Kumasi Metropolitan Assembly

KUMASI METROPOLITAN Copyright (c) 2014 Ghana Statistical Service ii PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT No meaningful developmental activity can be undertaken without taking into account the characteristics of the population for whom the activity is targeted. The size of the population and its spatial distribution, growth and change over time, in addition to its socio-economic characteristics are all important in development planning. A population census is the most important source of data on the size, composition, growth and distribution of a country’s population at the national and sub-national levels. Data from the 2010 Population and Housing Census (PHC) will serve as reference for equitable distribution of national resources and government services, including the allocation of government funds among various regions, districts and other sub-national populations to education, health and other social services. The Ghana Statistical Service (GSS) is delighted to provide data users, especially the Metropolitan, Municipal and District Assemblies, with district-level analytical reports based on the 2010 PHC data to facilitate their planning and decision-making. The District Analytical Report for the Kumasi Metropolitan is one of the 216 district census reports aimed at making data available to planners and decision makers at the district level. In addition to presenting the district profile, the report discusses the social and economic dimensions of demographic variables and their implications for policy formulation, planning and interventions. The conclusions and recommendations drawn from the district report are expected to serve as a basis for improving the quality of life of Ghanaians through evidence- based decision-making, monitoring and evaluation of developmental goals and intervention programmes. -

Public Procurement Authority. Draft Entity Categorization List

PUBLIC PROCUREMENT AUTHORITY. DRAFT ENTITY CATEGORIZATION LIST A Special Constitutional Bodies Bank of Ghana Council of State Judicial Service Parliament B Independent Constitutional Bodies Commission on Human Rights and Administrative Justice Electoral Commission Ghana Audit Service Lands Commission Local Government Service Secretariat National Commission for Civic Education National Development Planning Commission National Media Commission Office of the Head of Civil Service Public Service Commission Veterans Association of Ghana Ministries Ministry for the Interior Ministry of Chieftaincy and Traditional Affairs Ministry of Communications Ministry of Defence Ministry of Education Ministry of Employment and Labour Relations Ministry of Environment, Science, Technology and Innovation Ministry of Finance Ministry Of Fisheries And Aquaculture Development Ministry of Food & Agriculture Ministry Of Foreign Affairs And Regional Integration Ministry of Gender, Children and Social protection Ministry of Health Ministry of Justice & Attorney General Ministry of Lands and Natural Resources Ministry of Local Government and Rural Development Ministry of Petroleum Ministry of Power PUBLIC PROCUREMENT AUTHORITY. DRAFT ENTITY CATEGORIZATION LIST Ministry of Roads and Highways Ministry of Tourism, Culture and Creative Arts Ministry of Trade and Industry Ministry of Transport Ministry of Water Resources, Works & Housing Ministry Of Youth And Sports Office of the President Office of President Regional Co-ordinating Council Ashanti - Regional Co-ordinating -

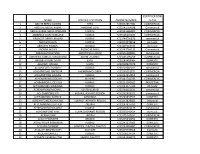

Name Specific Location Phone Number Certification Class

CERTIFICATION NAME SPECIFIC LOCATION PHONE NUMBER CLASS 1 ABAYIE BERKO AKWASI TEPA +233542854981 COMMERCIAL 2 ABDULAI ABDUL-RAZAK MABANG TEPA +233242764598 Commercial 3 ABDUL-KARIM ABDUL RAHMAN KUMASI +233243286809 COMMERCIAL 4 ABEBRESE DJAN ROWLAND KUMASI +233506264844 COMMERCIAL 5 ABOAGYE DANIEL AKWASI KUMASI +233244756870 commercial 6 ABOAGYE ELVIS KUMASI +233242978816 domestic 7 ABOAGYE KWAME BEKWAI +233207163334 domestic 8 ABORAH MOSES BUOHO KUMASI +233247764133 Commercial 9 ABRAHAM BOATENG AKROPONG KUMASI +233246188985 commercial 10 ABROKWA SAMUEL KORANTENG ADUM , KUMASI +233246590209 COMMERCIAL 11 ABUGRI AYAGRI DAVID EJISU +233249458064 DOMESTIC 12 ABUKARI INUSAH EJURA +233200937079 DOMESTIC 13 ACCOMFORD RICHARD KUMASI +233201682011 commercial 14 ACHEAMPONG BAFFOUR AHENEMAKOKOBEN +233248253831 COMMERCIAL 15 ACHEAMPONG AKWASI KUMASI +233242954852 commercial 16 ACHEAMPONG GIDEON MAAKRO +233241744743 COMMERCIAL 17 ACHEAMPONG JOE ELLIS KUMASI +233244560405 INDUSTRIAL 18 ACHEAMPONG KWABENA KUMASI +233243375366 domestic 19 ACHEAMPONG MICHAEL ASAFO-KUMASI +233244102431 commercial 20 ACHEAMPONG NTI KUMASI, ASHANTI REGION +233262428325 commercial 21 ACHEAMPONG PATRICK KONONGO +233249833553 DOMESTIC 22 ACHEAMPONG RICHMOND KUMASI ASHANTI REGION +233243828683 Industrial 23 ACHEAMPONG STEPHEN OBUASI +233247937033 DOMESTIC 24 ACHEAMPONG WILLIAM KUMASI +233203321176 commercial 25 ACHEAMPONG YAW KUMASI,ASHANTI REGION +233265042424 domestic 26 ACKAH JOHN OBUASI +233275247651 COMMERCIAL 27 ACKAH PADMORE BEKWAI +233245340252 DOMESTIC 28 ACKAH PHILIP -

Promoting Local Development in Atwima Nwabiagya Through a Hybrid of Cultures

PROMOTING LOCAL DEVELOPMENT IN ATWIMA NWABIAGYA THROUGH A HYBRID OF CULTURES By Hannah Serwah Bonsu (Bed Art Education) A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS IN AFRICAN ART AND CULTURE Faculty of Art College of Art and Social Sciences MAY 2010 (c) 2010, Department of General Art Studies DECLARATION I hereby declare that this submission is my own work towards the MA African Art Culture Degree and that to the best of my knowledge, it contains no material previously published by another person nor material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree of the university, except where due acknowledgement has been made in the text. HANNAH SERWAH BONSU (20065012) .…………………….. ………………… (Student Name) I.D. No. Signature Date Certified by DR. OPAMSHEN OSEI AGYEMAN …………………..……… …………………. (Supervisor) Signature Date Certified by DR. JOE ADU-AGYEM .........……….………………… ………………………. (Head of Department) Signature Date i ABSTRACT This study investigates hybrid cultures of the people of the Atwima Nwabiagya District of the Ashanti region of Ghana and the various ways by which these hybrid cultures have promoted local development in the district. The study is based on the assumption that the culture of the people of Atwima Nwabiagya, and some other foreign cultures have intermingled to create a hybrid of cultures which are being used to promote development in the district. The research also proceeds on the grounds that current cultural practices of the people of Atwima Nwabiagya are predominantly hybrid in form and any discussion of the socio-economic development issues of the district must be approached from the perspective of cultural hybridity. -

(CSM) Richard Bayel Trumah (BA. Geography and Rura

RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN SELECTED CLIMATIC VARIABLES AND CEREBROSPINAL MENINGITIS (CSM) Richard Bayel Trumah (BA. Geography and Rural Development) A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Environmental Resources Management. June, 2013. DECLARATION I hereby declare that this work is the result of my own field research and it has not been submitted either in part or whole for any other degree elsewhere. Specific references and sources of information used have been duly acknowledged. Where there appear to be statement(s) which have similarity to any other statement(s) elsewhere but has or have not been acknowledged is/are my own statement(s) and not an attempt to plagiarize. Trumah Bayel Richard ..….………….....………… ..….………….....……… (Student) Signature Date Certified by: Mr. John Ayer ..….………….....………… ..….………….....……… (Supervisor) Signature Date Certified by: Professor Samuel Kwofie ..….………….....………… ..….………….....……… (Head of Department) Signature Date ii DEDICATION To my parents, Mr. Joseph Trumah Bayel and Mrs. Baduro Trumah and my siblings. I dedicate this work to them for their love and support during the duration of the programme. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT My deepest appreciation goes to the Almighty God for His divine protection and guidance throughout this post graduate study. I am particularly grateful to my academic supervisors Mr. John Ayer and Dr. Dadson Awunyo-Vitor for their patience, guidance, support, corrections and comments made for a successful completion of this thesis. My sincere gratitude to all my lecturers on the Environmental Resources Management program and staff of the Department of Materials Engineering, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology. -

Northern Volta Ashanti Brong Ahafo Western Eastern Upper West

GWCL/AVRL Systems, Service Areas and Towns and Cities Served *# (!BAWKU BAWKU *# Legend Legend (! Upper East Water use in GWCL/AVRL Service Areas (AVRL 2007) NAVRONGO *#!(*# GWCL/AVRL system (AVRL 2007) NAVRONGO Upp(!er East Design plant capacity BOLGATANGA *# < 2000 m^3/day *# 2000 - 5000 m^3/day water use, tanker 5000 - 10000 m^3/day *# water use, domestic connection Upper West water use, commercial connections Upper West *# 10000 - 50000 m^3/day water use, industrial connections water use, industrial connections > 50000 m^3/day *# water use, sachet producers *# water use, unmetered standpipes Served town / city (!WA WA water use, metered standpipes Population (GSS 2000) Main road !( 1000 - 5000 Water body (! 5001 - 15,000 Region *# (! 15,001 - 30,000 !*# (! 30,001 - 50,000 (YENDI Northern YENDI TAMALE Norther(!nTAMALE (!50,001 - 100,000 (!*# DAMONGO (!> 100,000 Link between system and served town Main road Water body Region Brong Ahafo Brong Ahafo *# *# *# *# (!TECHIMAN (! TECHIMAN WORAWORA ! (!*# (BEREKUM *# JASIKAN BEREKUM (!SUNYANI Volta SUNYANI Volta !(*# *# DWOMMO !(*# *# NKONYA AHENKRO! HOHOE (HOHOE (! DWOMMO BIASO *# *# BIASO *# (! M(!AMPONG *# !( TEPA # (!*# MAMPONG ACHERENSUA * !( KPANDU (! SO*#VIE KPANDU AGONA !( TEPA (!*# ANFOEGA DZANA (!*# ACHERENSUA *# (!ASOKORE KPEDZE As*#hanti *# Ashanti *# KUMASI (!KUMASI (! KONONGO *# *# *# *# (! (!HO KONONGO HO ! !( TSITO Eastern N(KAWKAW ANUM NKAWKAW *# *# E(!a*#stern ANYINAM !( (! (! OSINOBEGORO *# KWABENG *#!( *# (! BUNSO *# (! ASUOM JUAPONG *# *#*# (! NEW TAFO # !( # NEW TAFO * -

Chapter 3 Present Situation of Ghana, Ashanti Region and Greater Kumasi Sub-Region 3.1 Past Development Trend and Current Development Policies of Ghana

13-203 13-203 The Study on the Comprehensive Urban Development Plan for Greater Kumasi in the Republic of Ghana Final Report Table of Contents Volume 1 Page Study Area: Greater Kumasi Sub-Region ................................................................................. 1 Photos of Greater Kumasi Sub-Region ..................................................................................... 2 Brief on the Study Project ......................................................................................................... 3 Executive Summary .................................................................................................................. 4 Conclusion ............................................................................................................................... 14 Part I Introduction Chapter 1 Introduction 1.1 Background .................................................................................................................. 1-1 1.2 Goals of the Study Project ............................................................................................ 1-2 1.3 Objectives of the Study Project .................................................................................... 1-2 1.4 Study Area .................................................................................................................... 1-3 1.5 Executive Agency, Implementing Agency and Other Counterpart Agencies ............... 1-3 1.6 Phases of the Project ................................................................................................... -

Akyemj C. 1700-1874 a STUDY in INTER-STATE RELATIONS in PRE-COLONIAL GOLD COAST Thesis Presented to the University of London

AKYEMj c. 1700-1874 A STUDY IN INTER-STATE RELATIONS IN PRE-COLONIAL GOLD COAST Thesis presented to the University of London for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by STEPHEN FRED AFFRIFAH JANUARY 1976. ProQuest Number: 11010458 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11010458 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 ABSTRACT During the first quarter of the eighteenth century and long after, Bosome led a politically unexciting life. In contrast, the other two Akyera states, Abuakwa and Kotoku, pursued an aggressive foreign policy and tightly guarded their independence against hostile neighbours. Between 1730 and 17^2 they acquired imperial domination over the eastern half of the Gold Coast west of the Volta. In 17^> however, Kotoku succumbed to Asante authority. Abuakwa resisted Asante but yielded to that power in 1783* The fall of the Akyem empire increased the area of Asante domination. The Asante yoke proved unbearable; consequently between 1810 and 1831 the Akyem states, as members of an Afro-European alliance, fought a successful war of independence against that power. -

TABLE of CONTENTS Page

FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS (FAO) ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ SUSTAINABLE FISHERIES LIVELIHOODS PROGRAMME (SFLP) GCP/INT/735/UK PILOT PROJECT 1 “IMPROVEMENT OF THE POLICIES AND INSTITUTIONS FOR CO-MANAGEMENT IN INLAND WATERS THE ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL CONTRIBUTION OF FISHERIES TO GROSS DOMESTIC PRODUCT AND RURAL DEVELOPMENT IN GHANA FINAL REPORT by Daniel Bruce Sarpong Agricultural Economist, Department of Agricultural Economics & Agribusiness, University of Ghana Samuel N.K. Quaatey Fisheries Specialist, Fisheries Department, MoFA Simon Kwadzogah Harvey Statistician, National Accounts Unit, Ghana Statistical Service June 2005 TABLE OF CONTENTS page List of Tables and Figures 2 List of Abbreviations 2 Executive Summary 4 1.0 Introduction: Background 8 1.1 The TOR and Scope of Study 12 1.2 The Study Team 12 2.0 Methodology of Study 13 2.1 Data Requirements 13 2.2 Estimations of the contribution of the fisheries sector to the national economy 14 2.3 Evaluating the Economic and Social Values of the Fisheries Sector 14 2.4 Review of Methodologies 14 2.5 Challenges in the application of methodology in computing the contribution of the Fisheries sector 16 2.6 Analysis of the contribution of the fisheries sector to national and socio-economic development: Reviews from literature of other countries 17 3.0 Brief Profile of the Selected Fishery Districts 21 3.1 Tema Municipal Assembly (TMA) 21 3.2 Gomoa Drictict Assembly (GDA) 22 3.3 Kpando