How Perceived Semantic Expression Explains Liking of Previously Unknown Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

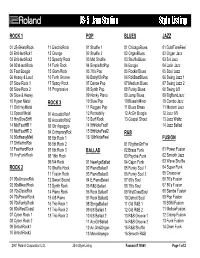

PTSVNWU JS-5 Jam Station Style Listing

PTSVNWU JS-5 Jam Station Style Listing ROCK 1 POP BLUES JAZZ 01 JS-5HardRock 11 ElectricRock 01 Shuffle 1 01 ChicagoBlues 01 DublTimeFeel 02 BritHardRck1 12 Grunge 02 Shuffle 2 02 OrganBlues 02 Organ Jazz 03 BritHardRck2 13 Speedy Rock 03 Mid Shuffle 03 ShuffleBlues 03 5/4 Jazz 04 80'sHardRock 14 Funk Rock 04 Simple8btPop 04 Boogie 04 Latin Jazz 05 Fast Boogie 15 Glam Rock 05 70's Pop 05 Rockin'Blues 05 Soul Jazz 06 Heavy & Loud 16 Funk Groove 06 Early80'sPop 06 RckBeatBlues 06 Swing Jazz 1 07 Slow Rock 1 17 Spacy Rock 07 Dance Pop 07 Medium Blues 07 Swing Jazz 2 08 Slow Rock 2 18 Progressive 08 Synth Pop 08 Funky Blues 08 Swing 6/8 09 Slow & Heavy 09 Honky Piano 09 Jump Blues 09 BigBandJazz 10 Hyper Metal ROCK 3 10 Slow Pop 10 BluesInMinor 10 Combo Jazz 11 Old HvyMetal 11 Reggae Pop 11 Blues Brass 11 Modern Jazz 12 Speed Metal 01 AcousticRck1 12 Rockabilly 12 AcGtr Boogie 12 Jazz 6/8 13 HvySlowShffl 02 AcousticRck2 13 Surf Rock 13 Gospel Shout 13 Jazz Waltz 14 MidFastHR 1 03 Gtr Arpeggio 14 8thNoteFeel1 14 Jazz Ballad 15 MidFastHR 2 04 CntmpraryRck 15 8thNoteFeel2 R&B 16 80sHeavyMetl 05 8bt Rock 1 16 16thNoteFeel FUSION 17 ShffleHrdRck 06 8bt Rock 2 01 RhythmGtrFnk 18 FastHardRock 07 8bt Rock 3 BALLAD 02 Brass Funk 01 Power Fusion 19 HvyFunkRock 08 16bt Rock 03 Psyche-Funk 02 Smooth Jazz 09 5/4 Rock 01 NewAgeBallad 04 Cajun Funk 03 Wave Shuffle ROCK 2 10 Shuffle Rock 02 PianoBallad1 05 Funky Soul 1 04 Super Funk 11 Fusion Rock 03 PianoBallad2 06 Funky Soul 2 05 Crossover 01 90sGrooveRck 12 Sweet Sound 04 E.PianoBalad 07 60's Soul 06 -

“Rapper's Delight”

1 “Rapper’s Delight” From Genre-less to New Genre I was approached in ’77. A gentleman walked up to me and said, “We can put what you’re doing on a record.” I would have to admit that I was blind. I didn’t think that somebody else would want to hear a record re-recorded onto another record with talking on it. I didn’t think it would reach the masses like that. I didn’t see it. I knew of all the crews that had any sort of juice and power, or that was drawing crowds. So here it is two years later and I hear, “To the hip-hop, to the bang to the boogie,” and it’s not Bam, Herc, Breakout, AJ. Who is this?1 DJ Grandmaster Flash I did not think it was conceivable that there would be such thing as a hip-hop record. I could not see it. I’m like, record? Fuck, how you gon’ put hip-hop onto a record? ’Cause it was a whole gig, you know? How you gon’ put three hours on a record? Bam! They made “Rapper’s Delight.” And the ironic twist is not how long that record was, but how short it was. I’m thinking, “Man, they cut that shit down to fifteen minutes?” It was a miracle.2 MC Chuck D [“Rapper’s Delight”] is a disco record with rapping on it. So we could do that. We were trying to make a buck.3 Richard Taninbaum (percussion) As early as May of 1979, Billboard magazine noted the growing popularity of “rapping DJs” performing live for clubgoers at New York City’s black discos.4 But it was not until September of the same year that the trend gar- nered widespread attention, with the release of the Sugarhill Gang’s “Rapper’s Delight,” a fifteen-minute track powered by humorous party rhymes and a relentlessly funky bass line that took the country by storm and introduced a national audience to rap. -

Music 3500: American Music This Final Exam Is Comprehensive —It Covers the Entire Course (Monday December Starting at 5PM In

FINAL EXAM STUDY GUIDE Music 3500: American Music This final exam is comprehensive —it covers the entire course (Monday December starting at 5PM in Knauss Hall 2452) Exam Format: 70 questions (each question is worth 4 points), plus a 40-point "fill-in-the-chart" (described below) (these two things total a maximum of 320 possible points toward your final course grade total). The format of the 70-question computer-graded section of the final exam will be: ...Matching ...Multiple Choice ...True/False (from text readings, class lectures, YouTube video links) General study recommendations: - Do the online quiz assignments for Chapters 1-9 (these must be completed by Monday April 24) ---------- For the Computer-Graded part of the final exam: 1. Know the definitions of Important Terms at the ends of Chapters 2-8 - Chapter 1 (textbook, page 5) -- know "popular music," "roots music," "Classical art- music" - Chapter 2 (textbook, page 19) -- know "old-time music," "hot jazz," "race music" - Chapter 3 (textbook, page 31) -- know "bebop," "big-band," "boogie-woogie" - Chapter 4 (textbook, page 42) -- know "backbeat," "chance music," "cool jazz," "multi- serialism," "rhythm & blues," "soul" - Chapter 5 (textbook, page 52) -- know "soundtrack," "free jazz" - Chapter 6 (textbook, pages 58-59) -- know "fusion," minimalism," - Chapter 7 (textbook, pages 69-70) -- know "techno," "smooth jazz," "hip-hop" - Chapter 8 (textbook, page 81) -- know "sound art" 2. Know which decade the following music technologies came from: (Review the chronological order of -

IN SEARCH of WARMER CLIMES Following a Move to LA, Bonobo Returns to Ninja Tune with New LP, ‘Migration’

MUSIC ONE STOP SHOP February’s tunes reviewed p.106 THE LONG GAME Albums arriving this month p.128 MIX ‘N’ MATCH Compilations not to miss p.132 IN SEARCH OF WARMER CLIMES Following a move to LA, Bonobo returns to Ninja Tune with new LP, ‘Migration’... p.129 djmag.com 105 HOUSE BEN ARNOLD QUICKIES Roberto Clementi Avesys EP [email protected] Pets Recordings 8.0 Sheer class from Roberto Clementi on Pets. The title track is brooding and brilliant, thick with drama, while 'Landing A Man'’s relentless thump betrays a soft and gentle side. Lovely. Jagwar Ma Give Me A Reason (Michael Mayer Does The Amoeba Remix) Marathon MONEY 8.0 SHOT! Showing that he remains the master (and managing Baba Stiltz to do so in under seven minutes too), Michael Mayer Is Everything smashes this remix of baggy dance-pop dudes Studio Barnhus Jagwar Ma out of the park. 9.5 The unnecessarily young Baba Satori Stiltz (he's 22) is producing Imani's Dress intricate, brilliantly odd house Crosstown Rebels music that bearded weirdos 8.0 twice his age would give their all chopped hardcore loops, and a brilliance from Tact Recordings Crosstown is throwing weight behind the rather mid-life crises for. Think the bouncing bassline. Sublime work. comes courtesy of roadman (the unique sound of Satori this year — there's an album dizzying brilliance of Robag small 'r' is intentional), aka coming — but ignore the understatedly epic Ewan Whrume for a reference point, Dorsia Richard Fletcher. He's also Tact's Pearson mixes of 'Imani's Dress' at your peril. -

The DIY Careers of Techno and Drum 'N' Bass Djs in Vienna

Cross-Dressing to Backbeats: The Status of the Electroclash Producer and the Politics of Electronic Music Feature Article David Madden Concordia University (Canada) Abstract Addressing the international emergence of electroclash at the turn of the millenium, this article investigates the distinct character of the genre and its related production practices, both in and out of the studio. Electroclash combines the extended pulsing sections of techno, house and other dance musics with the trashier energy of rock and new wave. The genre signals an attempt to reinvigorate dance music with a sense of sexuality, personality and irony. Electroclash also emphasizes, rather than hides, the European, trashy elements of electronic dance music. The coming together of rock and electro is examined vis-à-vis the ongoing changing sociality of music production/ distribution and the changing role of the producer. Numerous women, whether as solo producers, or in the context of collaborative groups, significantly contributed to shaping the aesthetics and production practices of electroclash, an anomaly in the history of popular music and electronic music, where the role of the producer has typically been associated with men. These changes are discussed in relation to the way electroclash producers Peaches, Le Tigre, Chicks on Speed, and Miss Kittin and the Hacker often used a hybrid approach to production that involves the integration of new(er) technologies, such as laptops containing various audio production softwares with older, inexpensive keyboards, microphones, samplers and drum machines to achieve the ironic backbeat laden hybrid electro-rock sound. Keywords: electroclash; music producers; studio production; gender; electro; electronic dance music Dancecult: Journal of Electronic Dance Music Culture 4(2): 27–47 ISSN 1947-5403 ©2011 Dancecult http://dj.dancecult.net DOI: 10.12801/1947-5403.2012.04.02.02 28 Dancecult 4(2) David Madden is a PhD Candidate (A.B.D.) in Communications at Concordia University (Montreal, QC). -

MUSIC, Dvds, PROGRAMS, PE CLASSES & SOUND SYSTEMS

MUSIC, DVDs, PROGRAMS, PE CLASSES & SOUND SYSTEMS ® and “Hi! I’m Christy Lane, creator of Dare to Dance owner of Christy Lane Enterprises. How can we help you? As you browse through this catalog, you will notice we expanded our line of products and services. When our company was established 20 years ago our philosophy was simple. To educate children that dance can benefit them physically, mentally, That's me on my first video shoot. socially, and emotionally. We did this by producing quality educational products for the physical Catalog Listings: education teachers and dance studio instructors. LINE DANCING Our customer base has expanded tremendously over PARTY DANCING the years and so has the popularity of dance. Now, DECADE DANCING moms, dads, single adults, seniors, and kids who HIP HOP have never danced before are dancing! So join the PARTNER/BALLROOM fun!” LATIN DANCING SQUARE DANCING AMERICA SPORTS & NOVELTY MULTICULTURAL FOLK Christy Lane is one of America’s most well-known and respected dance instructors. Her DANCING extensive dance training has led her to become an acknowledged dance educator, producer, choreographer, and writer. Her work has been recognized by U.S. News and World Report, AFRICAN-CARIBBEAN American Fitness, USA Today and Shape Magazine. Her credits include Disney, Pepsi and DANCING Capezio to name a few. A former private dance studio owner, she tours nationally and her PHYSICAL FITNESS conventions and workshops have delighted thousands of all ages. MUSIC EDITING JAZZ DANCING TAP DANCING DANCE CONVENTIONS HOLIDAY DANCE SHIRTS DANCE FLOORS SOUND SYSTEMS & MICROPHONES TEACHER WORKSHOPS “Christy Lane has the magic to motivate the non-dancer and insight to move DANCE SCHOOL ASSEMBLIES accomplished dancers to the next level.”-Bud Turner, P.E. -

Popular Music As Entertainment Communication: How Perceived Semantic Expression Explains Liking Previously Unknown Music

This is a repository copy of Popular Music as Entertainment Communication: How Perceived Semantic Expression Explains Liking Previously Unknown Music. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/163797/ Version: Published Version Article: Lepa, Steffen, Steffens, Jochen, Herzog, Martin et al. (1 more author) (2020) Popular Music as Entertainment Communication: How Perceived Semantic Expression Explains Liking Previously Unknown Music. Media and Communication. ISSN 2183-2439 10.17645/mac.v8i3.3153 Reuse This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) licence. This licence allows you to distribute, remix, tweak, and build upon the work, even commercially, as long as you credit the authors for the original work. More information and the full terms of the licence here: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Media and Communication (ISSN: 2183–2439) 2020, Volume 8, Issue 3, Pages 191–204 DOI: 10.17645/mac.v8i3.3153 Article Popular Music as Entertainment Communication: How Perceived Semantic Expression Explains Liking of Previously Unknown Music Steffen Lepa 1,*, Jochen Steffens 2, Martin Herzog 1 and Hauke Egermann 3 1 Audio Communication Group, TU Berlin, 10587 Berlin, Germany; E-Mail: [email protected] (S.L.), [email protected] (M.H.) 2 Media Department, University of Applied Sciences Düsseldorf, 40476 Düsseldorf, Germany; E-Mail: [email protected] 3 York Music Psychology Group, University of York, York, YO10 5DD, UK; E-Mail: [email protected] * Corresponding author Submitted: 14 April 2020 | Accepted: 26 June 2020 | Published: 13 August 2020 Abstract Our contribution addresses popular music as essential part of media entertainment offerings. -

Is Rock Music in Decline? a Business Perspective

Jose Dailos Cabrera Laasanen Is Rock Music in Decline? A Business Perspective Helsinki Metropolia University of Applied Sciences Bachelor of Business Administration International Business and Logistics 1405484 22nd March 2018 Abstract Author(s) Jose Dailos Cabrera Laasanen Title Is Rock Music in Decline? A Business Perspective Number of Pages 45 Date 22.03.2018 Degree Bachelor of Business Administration Degree Programme International Business and Logistics Instructor(s) Michael Keaney, Senior Lecturer Rock music has great importance in the recent history of human kind, and it is interesting to understand the reasons of its de- cline, if it actually exists. Its legacy will never disappear, and it will always be a great influence for new artists but is important to find out the reasons why it has become what it is in now, and what is the expected future for the genre. This project is going to be focused on the analysis of some im- portant business aspects related with rock music and its de- cline, if exists. The collapse of Gibson guitars will be analyzed, because if rock music is in decline, then the collapse of Gibson is a good evidence of this. Also, the performance of independ- ent and major record labels through history will be analyzed to understand better the health state of the genre. The same with music festivals that today seem to be increasing their popularity at the expense of smaller types of live-music events. Keywords Rock, music, legacy, influence, artists, reasons, expected, fu- ture, genre, analysis, business, collapse, -

Hyperdub's Kode9 & the Spaceape Have Left Tired

With their new album ‘Black Sun’, Hyperdub’s Kode9 & the Spaceape have left tired genre pigeonholes behind, switched up their sound and conjured a bright, neon-lit sci-fi parable of futuristic house, fractured breakbeats, cryptic poetry and bleeps, where nothing is as it seems. Infl uenced by JG Ballard, Solaris, UK funky, THX1138 and Prince Far-I, it’s a dystopian funk epic that should see them reach a whole new audience. DJmag fi nds out more… Words: BEN MURPHY cience fi ction and electronic changed, became something other but still enabled through a gauze of Kode9’s gloopy, buzzing music have a chequered life, what would that be like?” wonders Spaceape. computerfunk, living colours that stretch through history together. Both are Spaceape’s oblique, cryptic lyrics, and chattering, often obsessed with the Camberwell, South London-dwelling Glaswegian hypermodern beats, a machine-gun spray of broken future, interwoven with new Kode9 (Steve Goodman) will be familiar to many rhythms and weird house music, ‘Black Sun’ is what technology and look to electronic music fans as the owner of the peerless, happens when two attuned brains with a distinct transport the reader, viewer or always one-step-ahead label Hyperdub (responsible conceptual vision of how they want their music to listener to other worlds. But for launching mavericks like Burial, Ikonika, Zomby sound — and what they want it to stand for — collide. it’s rare that beats ‘n’ and Darkstar into the world), as a globetrotting DJ “We share a lot in common and I guess that’s why, basslines are able to allude to fantasy without and producer who’s played a prominent part in the when we work together, it comes out sounding like it seeming contrived, all naff aliens and X Files recent evolutions and mutations of dance, from does,” says Spaceape on the recording of the album codswallop. -

NEW WAVE Pablo Esteban

La ola que cambió el rumbo desde UK PABLO ESTEBAN New Wave La Ola que cambió el rumbo desde UK ! ! ! ! Pablo Esteban Febrero 2014 NEW WAVE 1. La ola que cambió el rumbo desde UK PABLO ESTEBAN New Wave ! Índice ! 1. Definición 1.1. Término 1.2. Contexto histórico 1.3. Ideología política y social de las bandas 2. Filosofía del movimiento 2.1. Influencias 2.2.Historia 2.3. Subgéneros SYNTH POP DARKWAVE ROCK ALTERNATIVO NEW ROMANTIC 3. Principales Bandas 4. Repercusión en Reino Unido 5. Expansión de la Ola 6. Conclusión ! ! ! ! NEW WAVE 1. La ola que cambió el rumbo desde UK PABLO ESTEBAN New Wave 1 Definición ! 1.1. Término El término New wave proviene de «new wave rock music» y significa Nueva Ola, refiriéndose a la reinterpretación de la primera ola que arrancó a principios de los 70 (nacimiento del punk-rock), es un término global para varios estilos pop/rock que nacieron a finales de la década de 1970 (específicamente en 1978) como derivado del punk y con vínculos del rock de principios de década y que evolucionó durante los años 80 (hasta aproximadamente el año 1988), proyectándose como un movimiento musical y estético (tanto en la forma de pensar, actuar, llevar el pelo o vestir). Se mantuvo prácticamente análogo al punk rock antes de ramificarse como un género distintamente identificado, incorporando música electrónica, experimental, mod, disco y pop. Posteriormente creó subgéneros propios y fusiones, el new wave nació en Inglaterra y se extendió con gran relevancia hacia EEUU y mas concretamente a Nueva York donde pasó a llamarse Post-punk y posteriormente a independizarse y diferenciarse de sus orígenes, surgió como una nueva forma de rock que amplió los límites del mismo, infundiéndole su alma a la música de los años 80 y legando para la posteridad diversas culturales. -

As Ondas Musicais Do Pós-Manguebit

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO PERNAMBUCO CENTRO DE ARTES E COMUNICAÇÃO DEPARTAMENTO DE COMUNICAÇÃO SOCIAL PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM COMUNICAÇÃO RICARDO CÉSAR CAMPOS MAIA JÚNIOR AS ONDAS MUSICAIS DO PÓS-MANGUEBIT RECIFE 2016 RICARDO CÉSAR CAMPOS MAIA JÚNIOR AS ONDAS MUSICAIS DO PÓS-MANGUEBIT Tese apresentada à Coordenação do Programa de Pós Graduação em Comunicação, da Universidade Federal de Pernambuco, como requisito para a obtenção do grau de Doutor em Comunicação, sob orientação do Prof. Dr. Jeder Silveira Janotti Junior. RECIFE 2016 Catalogação na fonte Bibliotecária Maria Valéria Baltar de Abreu Vasconcelos, CRB4-439 M217o Maia Júnior, Ricardo César Campos As ondas musicais do Pós - Manguebit / Ricardo César Campos Maia Júnior. – Recife, 2016. 231 f.: il. Orientador: Jeder Silveira Janotti Junior. Tese (Doutorado) – Universidade Federal de Pernambuco, CAC. Comunicação, 2016. Inclui referências e apêndices. 1. Comunicação. 2. Música - Pernambuco - Sec. XX. 3. Comunicação e cultura. 4. Música - Pernambuco - Movimento. 5. Músicos - Pernambuco. 6. Mangue (Música). I. Janotti Junior, Jeder Silveira (Orientador). II. Titulo. 302.23 CDD (22.ed.) UFPE (CAC 2016-191) AGRADECIMENTOS Obrigado aos que contribuíram para a realização intelectual desse texto: principalmente ao meu orientador, Jeder Silveira Janotti Junior por toda a dedicação, suporte e força nessa caminhada; aos membros da minha banca examinadora, além dos professores do Programa de Pós-Graduação em Comunicação da UFPE. Agradeço também por todo o suporte emocional dado nessa longa caminhada pela minha família, principalmente: minha avó, Mabel Morais, minha mãe, Eliane Pires de Morais Maia, minha esposa, Raquel Valentim e minha filha Nina Mabel. Para finalizar, dedico essa tese à memória do meu pai, Ricardo Maia. -

Contemporary Carioca: Technologies of Mixing in A

Con tempo C o n t e m p o r a r y raryC a r i o c a Cari oca ontemporary CCarioca Technologies of Mixing in a Brazilian Music Scene Frederick Moehn Duke University Press Durham anD LonDon 2012 © 2012 Duke University Press All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper ♾ Designed by Kristina Kachele Typeset in Quadraat and Ostrich Sans by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data appear on the last printed page of this book. Duke University Press gratefully acknowledges the support of Stony Brook University, which provided funds toward the publication of this book. For Brazil’s musical alchemists ontents Illustrations ix C Preface xi Acknowledgments xxiii Introduction 1 1 Marcos Suzano: A Carioca Blade Runner 25 2 Lenine: Pernambuco Speaking to the World 55 3 Pedro Luís and The Wall: Tupy Astronauts 92 4 Fernanda Abreu: Garota Carioca 130 5 Paulinho Moska: Difference and Repetition 167 6 On Cannibals and Chameleons 204 Appendix 1: About the Interviews, with a List of Interviews Cited 211 Appendix 2: Introductory Aspects of Marcos Suzano’s Pandeiro Method 215 Notes 219 References 245 Discography 267 Index 269 llustrations Map of Rio de Janeiro with inset of the South Zone 6 1 “mpb: Engajamento ou alienação?” debate invitation xii 2 Marcos Suzano’s favorite pandeiro (underside) 29 I 3 Marcos Suzano demonstrating his pandeiro and electronic foot pedal effects setup 34 4 A common basic samba pattern on pandeiro 48 5 One of Marcos Suzano’s pandeiro patterns 49 6 Marcos