Sounding and Writing a Nepali Public Sphere: the Music and Language of Jhyāure

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Final Senior Fellowship Report

FINAL SENIOR FELLOWSHIP REPORT NAME OF THE FIELD: DANCE AND DANCE MUSIC SUB FIELD: MANIPURI FILE NO : CCRT/SF – 3/106/2015 A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF TWO VAISHNAVISM INFLUENCED CLASSICAL DANCE FORM, SATRIYA AND MANIPURI, FROM THE NORTH EAST INDIA NAME : REKHA TALUKDAR KALITA VILL – SARPARA. PO – SARPARA. PS- PALASBARI (MIRZA) DIST – KAMRUP (ASSAM) PIN NO _ 781122 MOBILE NO – 9854491051 0 HISTORY OF SATRIYA AND MANIPURI DANCE Satrya Dance: To know the history of Satriya dance firstly we have to mention that it is a unique and completely self creation of the great Guru Mahapurusha Shri Shankardeva. Shri Shankardeva was a polymath, a saint, scholar, great poet, play Wright, social-religious reformer and a figure of importance in cultural and religious history of Assam and India. In the 15th and 16th century, the founder of Nava Vaishnavism Mahapurusha Shri Shankardeva created the beautiful dance form which is used in the act called the Ankiya Bhaona. 1 Today it is recognised as a prime Indian classical dance like the Bharatnatyam, Odishi, and Kathak etc. According to the Natya Shastra, and Abhinaya Darpan it is found that before Shankardeva's time i.e. in the 2nd century BC. Some traditional dances were performed in ancient Assam. Again in the Kalika Purana, which was written in the 11th century, we found that in that time also there were uses of songs, musical instruments and dance along with Mudras of 108 types. Those Mudras are used in the Ojha Pali dance and Satriya dance later as the “Nritya“ and “Nritya hasta”. Besides, we found proof that in the temples of ancient Assam, there were use of “Nati” and “Devadashi Nritya” to please God. -

EUROPEAN BULLETIN of HIMALAYAN RESEARCH EBHR | Issue 54 (2020)

54 Spring 2020 EBHR EUROPEAN BULLETIN OF HIMALAYAN RESEARCH EBHR | Issue 54 (2020) The European Bulletin of Himalayan Research (EBHR) was founded by the late Richard Burghart in 1991 and has appeared twice yearly ever since. It is the result of a partnership and is edited on a rotating basis between the Centre for Himalayan Studies (CEH: Centre d’études himalayennes) within the Centre national de la recherche scientifique (CNRS) in France, the South Asia Institute at Heidelberg University in Germany and the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) in the United Kingdom. From 2019 to 2023, EBHR is hosted at the Centre for Himalayan Studies. Co-editors Tristan Bruslé (CNRS-CEH), Stéphane Gros (CNRS-CEH), Philippe Ramirez (CNRS-CEH) Associate editor Arik Moran (University of Haifa), book review editor Copyeditor Bernadette Sellers (CNRS-CEH) The following email address should be used for subscription details and any correspondence regarding the journal: [email protected] Back issues of the journal are accessible on the Digital Himalaya platform: http://www.digitalhimalaya.com/ebhr Editorial Board Adhikari, Jagannath (Australian National University) Arora, Vibha (Indian Institute of Technology) Bleie, Tone (University of Tromsø) Campbell, Ben (Durham University) Chhetri, Mona (Australia India Institute) De Maaker, Erik (Leiden University) de Sales, Anne (CNRS-LESC) Dollfus, Pascale (CNRS-CEH) Gaenszle, Martin (University of Vienna) Gellner, David (University of Oxford) Grandin, Ingemar (Linköping University) Hausner, Sondra L. (University -

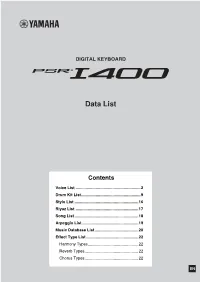

PSR-I400 Data List Voice List

DIGITAL KEYBOARD Data List Contents Voice List ..........................................................2 Drum Kit List.....................................................9 Style List .........................................................16 Riyaz List ........................................................17 Song List .........................................................18 Arpeggio List ..................................................19 Music Database List.......................................20 Effect Type List...............................................22 Harmony Types.............................................22 Reverb Types................................................22 Chorus Types................................................22 EN Voice List Maximum Polyphony The instrument has 48-note maximum polyphony. This means that it NOTE can play a maximum of up to 48 notes at once, regardless of what • The Voice List includes MIDI program change numbers functions are used. Auto accompaniment uses a number of the for each voice. Use these program change numbers available notes, so when auto accompaniment is used the total number when playing the instrument via MIDI from an external of available notes for playing on the keyboard is correspondingly device. reduced. The same applies to the Split Voice and Song functions. If the • Program change numbers are often specified as maximum polyphony is exceeded, earlier played notes will be cut off and numbers “0–127.” Since this list uses a “1–128” the most recent notes have -

Classification of Indian Musical Instruments with the General

Classification of Indian Musical Instruments With the general background and perspective of the entire field of Indian Instrumental Music as explained in previous chapters, this study will now proceed towards a brief description of Indian Musical Instruments. Musical Instruments of all kinds and categories were invented by the exponents of the different times and places, but for the technical purposes a systematic-classification of these instruments was deemed necessary from the ancient time. The classification prevalent those days was formulated in India at least two thousands years ago. The first reference is in the Natyashastra of Bharata. He classified them as ‘Ghana Vadya’, ‘Avanaddha Vadya’, ‘Sushira Vadya’ and ‘Tata Vadya’.1 Bharata used word ‘Atodhya Vadya’ for musical instruments. The term Atodhya is explained earlier than in Amarkosa and Bharata might have adopted it. References: Some references with respect to classification of Indian Musical Instruments are listed below: 1. Bharata refers Musical Instrument as ‘Atodhya Vadya’. Vishnudharmotta Purana describes Atodhya (Ch. XIX) of four types – Tata, Avnaddha, Ghana and Sushira. Later, the term ‘Vitata’ began to be used by some writers in place of Avnaddha. 2. According to Sangita Damodara, Tata Vadyas are favorite of the God, Sushira Vadyas favourite of the Gandharvas, whereas Avnaddha Vadyas of the Rakshasas, while Ghana Vadyas are played by Kinnars. 3. Bharata, Sarangdeva (Ch. VI) and others have classified the musical instruments under four heads: 1 Fundamentals of Indian Music, Dr. Swatantra Sharma , p-86 53 i. Tata (String Instruments) ii. Avanaddha (Instruments covered with membrane) iii. Sushira (Wind Instruments) iv. Ghana (Solid, or the Musical Instruments which are stuck against one another, such as Cymbals). -

DRUMS S21 Medium Snare 2 Rim Shot S22 Concert Snare Soft Exc 1 Bass Drum (Kick) S23 Concert Snare Hard Exc 1 No

Information When you need repair service, call your nearest Roland Service Center or authorized Roland distributor in your country as shown below. SINGAPORE PANAMA ITALY ISRAEL AFRICA Swee Lee Company SUPRO MUNDIAL, S.A. Roland Italy S. p. A. Halilit P. Greenspoon & 150 Sims Drive, Boulevard Andrews, Albrook, Viale delle Industrie 8, Sons Ltd. EGYPT SINGAPORE 387381 Panama City, REP. DE PANAMA 20020 Arese, Milano, ITALY 8 Retzif Ha'aliya Hashnya St. Al Fanny Trading Office TEL: 846-3676 TEL: 315-0101 TEL: (02) 937-78300 Tel-Aviv-Yafo ISRAEL 9, EBN Hagar A1 Askalany Street, TEL: (03) 6823666 ARD E1 Golf, Heliopolis, CRISTOFORI MUSIC PTE PARAGUAY NORWAY Cairo 11341, EGYPT LTD Distribuidora De Roland Scandinavia Avd. JORDAN TEL: 20-2-417-1828 Blk 3014, Bedok Industrial Park E, Instrumentos Musicales Kontor Norge AMMAN Trading Agency #02-2148, SINGAPORE 489980 J.E. Olear y ESQ. Manduvira Lilleakerveien 2 Postboks 95 245 Prince Mohammad St., REUNION TEL: 243 9555 Asuncion PARAGUAY Lilleaker N-0216 Oslo Amman 1118, JORDAN Maison FO - YAM Marcel TEL: (021) 492-124 NORWAY TEL: (06) 464-1200 25 Rue Jules Hermann, TAIWAN TEL: 273 0074 Chaudron - BP79 97 491 ROLAND TAIWAN PERU KUWAIT Ste Clotilde Cedex, ENTERPRISE CO., LTD. VIDEO Broadcast S.A. POLAND Easa Husain Al-Yousifi REUNION ISLAND Room 5, 9fl. No. 112 Chung Shan Portinari 199 (ESQ. HALS), P. P. H. Brzostowicz Abdullah Salem Street, TEL: (0262) 218-429 N.Road Sec.2, Taipei, TAIWAN, San Borja, Lima 41, UL. Gibraltarska 4. Safat, KUWAIT R.O.C. REP. OF PERU PL-03664 Warszawa POLAND TEL: 243-6399 SOUTH AFRICA TEL: (02) 2561 3339 TEL: (01) 4758226 TEL: (022) 679 44 19 That Other Music Shop LEBANON (PTY) Ltd. -

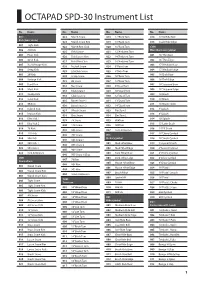

OCTAPAD SPD-30 Instrument List

OCTAPAD SPD-30 Instrument List No. Name No. Name No. Name No. Name KIK: 022 March Snare 018 12”Rock Tom 014 Sizzle Ride Bell Kick (bass drum) 023 March Snare Rim 019 13”Rock Tom 015 Sizzle Ride Edge 001 Tight Kick 024 March Rim Click 020 16”Rock Tom CYM: 002 Alt Kick Miscellaneous cymbal 025 Field Snare 021 12”Ambient Tom 003 Fiber Kick 001 16”Thin Bow 026 Field Snare Rim 022 14”Ambient Tom 004 Birch Kick 002 16”Thin Edge 027 Field Rim Click 023 16”Ambient Tom 005 RockVintage Kick 003 17”Medium Bow 028 NuJack Snare 024 6”Roto Tom 006 Deep Kick 004 17”Medium Edge 029 LiteClub Snare 025 8”Roto Tom 007 20”Kick 005 18”Dark Bow 030 2step Snare 026 10”Roto Tom 008 Vintage Kick 006 18”Dark Edge 031 BB Snare 027 12”Roto Tom 009 Hard Kick 007 18”Suspend Bow 032 Box Snare 028 6”Quad Tom 010 Meat Kick 008 18”Suspend Edge 033 Club Snare 1 029 10”Quad Tom 011 NuHip Kick 009 16”Brush 034 Club Snare 2 030 12”Quad Tom 012 Solid Kick 010 18”Brush 035 Barrel Snare 1 031 13”Quad Tom 013 BB Kick 011 18”Brush Sizzle 036 Barrel Snare 2 032 14”Quad Tom 014 Hybrid Kick 012 6”Splash 037 Whack Snare 033 ElecTom 1 015 Impact Kick 013 8”Splash 038 Elec Snare 034 ElecTom 2 016 Elec Kick 1 014 10”Splash 039 78 Snare 035 808Tom 017 Elec Kick 2 015 13”Latin Crash 040 110 Snare 036 909Tom 018 78 Kick 016 14”FX Crash 041 606 Snare 037 Tom Ambience 019 110 Kick 017 16”China Cymbal 042 707 Snare HH: 020 808 Kick Hi-hat cymbal 018 18”Swish Cymbal 043 808 Snare 1 021 909 Kick 1 001 Med Hihat Bow 019 3 Layered Crash 044 808 Snare 2 022 909 Kick 2 002 Med Hihat Edge 020 4”Accent -

4.1 Background

CHAPTER 4 GROWTH AND DEVELOPMENT OF NON-BENGALI PRESS AND SOME ASSOCIATIONS IN NON-BENGALI DOMINATED AREAS OF NORTH BENGAL 4.1 BACKGROUND In our Present chapter we have to discuss about some press publications and Associations, which have emerged from some Non-Bengali origin. In this context one question arises, why these non-Bengali institutions originated. From a broad perspective, it can be said that this is not unlikely due to some geographical and ethnical identity or background. We know that Indian history and culture is multi-dimensional and in this connection Bengal has all kinds of priority. In North Bengal also we find the same picture in respect of ethnicity and culture. In our previous chapter, we have mentioned very clearly about the geographical areas of North Bengal. (See Chapter 1) While observing about the cultural and intellectual activities of the people of North Bengal, it is found that the educated people and the intellectuals of Darjeeling District and some, area of Jalpaiguri (Duars) were publishing press and periodicals in different languages other than Bengali. During the period of our study we find a large number of vernacular publications from different parts of present North Bengal (six district). In this context one interesting and notable thing is that North Bengal was representing not only the Bengali newspapers. Journals and periodicals, but also English, Hindi, Nepali, Tibetan and Rajbanshi (local dialect) newspapers that enriched and focused the social, cultural and some other activities of North Bengal. In these activities of Darjeeling hill areas and some parts of Duars, the British rulers had a very important role to play. -

Modernism and Modern Nepali Poetry – Dr

Dancing Soul of Mount Everest Creator & Creation (Selected Modern Nepali Poems) Editing Advisors Dr. Govinda Raj Bhattarai Rajeshwor Karki Proposer Dr. Laxman Prasad Gautam Editor Momila Translator & Language Editor Mahesh Paudyal Publisher Nepali Kalasahitya Dot Com Pratishthan [Nepali Art & Literature Dot Com Foundation] (Under the project of Nepal Academy) Dancing Soul of Mount Everest Creator & Creation (Selected Modern Nepali Poems) Editor : Momila Translator & Language Editor : Mahesh Paudyal Publisher : Nepali Kalasahitya Dot Com Pratishthan (Nepali Art & Literature Dot Com Foundation) ©:Publisher Edition : First, 2011 Copies : 1001 Cover Design : Graphic Workshop Layout : Jeevan Nepal Printer : Modern Printing Press Kantipath, Kathmandu, Phone: 4253195 Price : NRs. 1,200.00 IRs. 1,000.00 US$ 25.00 Euro 20.00 ISBN: 978-9937-2-3657-7 DANCING SOUL OF MOUNT EVEREST (an anthology of selected modern Nepali poems) Editorial Context Heart-Transfer/Moksha Esteemed Readers! Here in editorial context, I extend words of gratitude that express themselves, though they might have remained apparently unexpressed. All of your accepted / unaccepted self-reflections shall become collages on the canvas of the history assimilated in this anthology. Dear Feelers! Wherever and whenever questions evolve, the existential consciousness of man keeps exploring the horizon of possibilities for the right answer even without the ultimate support to fall back upon. Existential revelations clearly dwell on the borderline, though it might be in a clash. In the present contexts, at places, questions of Nepali identity, modernity, representativeness, poetic quality, mainstream or periphery, temporal boundaries and limitations of number evolve – wanted or unwanted. Amidst the multitude of these questions, Dancing Soul of Mount Everest has assumed this accomplished form in its attempt to pervade the entirety as far as possible. -

JBD General Knowledge Keybook Book - 6

JBD General Knowledge and IQ Test : Book – 6 KEYWORD KEYWORD JBD General Knowledge and IQ Test : Book – 6 JBD General Knowledge Keybook Book - 6 CHAPTER 1 plant and animals lesson 1 : Water animals Page : 1 a. Turtle b. Goldfish c. Sea horse d. Sailfish e. Fish lesson 2 : mammals Page : 3 a. 2,00,000 glasses b. Flutterby c. Four d. Owl e. Over 25,000 f. Crane g. Crocodile h. Goliath Frog lesson 4 : amazing animals Page : 5 a. Leafy Seadragon b. Sun Bear c. Komondor Dog d. Angora Rabbit e. Red Panda f. Sloth g. Emperor Tamarin h. Tapir i. Hagfish j. Star nosed Mole k. Proboscis Moneky l. Axolotl Page : 6 a. Zyzzyva b. Antarctica c. Myrmecology d. Goose e. Flink f. Retangular lesson 6 : exciting Birds Page : 8 a. American Bittern b. Baikal Teal c. Barn Owl d. Bateleur e. Caspian Plover f. Chukar g. Coot h. Curlew i. Dunlin lesson 8 : Human Beings Page : 10 a. 1,03,689 b. 23,045 c. 16,80,000 d. 0.00007 e. 0.01715 f. 2.9 g. 3.25 lesson 9 : plants World page : 12 a. 84% b. 96% c. Thistle family d. Avacado e. Lily family f. Busy Lizzie g. Transplant seedling and small plants h. Venus Flytrap Page : 13 a. Marsh Marigold b. Cattail c. Arrowhead d. Duckweed e. Amazon lily f. Lotus g. Blue Pickerel weed h. Fairy Moss i. Parrot's Feather 46 JBD General Knowledge and IQ Test : Book – 6 KEYWORD KEYWORD JBD General Knowledge and IQ Test : Book – 6 Page : 14 a. -

Garritan World Instruments Complete Instrument List

Garritan World Instruments Complete Instrument List Garritan: World Instruments Complete Instrument List Africa: Sakara India: Sangban Arghul Bansuri 1 Sanza Mijwiz 1 Bansuri 2 Sistrum Mijwiz 2 Pungi Snake Charmer Tama (Talking Drum) Adodo Shenai Televi African Log Drum Shiva Whistle Tonetang (Stir Drum) Apentima Basic Indian Percussion Udu Drums Ashiko Chenda Begena Balafon Chimta Bolon Basic African Percussion Chippli Domu Bougarabou Dafli Kora Dawuro Damroo Ngoni Djembe Dhol Dondo China: Dholak Doun Ba Bawu Ghatam Atoke Di-Zi Ghungroo Axatse Guanzi Gong (Stinging Gong) Gankokwe Hulusi Hatheli Kagan Sheng Kanjeera Kpanlogo 1 Large Suona Khartal Kpanlogo 2 Medium Xiao Khol Kpanlogo 3 Combo Basic Chinese Percussion Manjeera Sogo Bianzhong Murchang Fontomfrom Bo Mridangam Gome Chinese Cymbals Naal Gyil Chinese Gongs Nagara Ibo Datangu Lion Drum Pakhawaj Kalimbas Pan Clappers Stir Drum Kenkeni Temple Bells Tablas Kpoko Kpoko Temple Blocks Tamte Krin Slit Drum Choazhou Guzheng Tasha Likembe Erhu Tavil Mbira Guzheng Udaku Morocco Drum Pipa Electric Sitar Nigerian Log Drum Yueqin Sarangi Sarangi Drone Thai Gong Uilleann Pipes Sitar Tibetan Cymbals Bone Flute 1 Tambura Tibetan Singing Bowls Bone Flute 2 Japan: Tibetan Bells Irish Flute Tingsha Shepherds Folk Pipe 1 Hichiriki Dan Tranh Shepherds Folk Pipe 2 Knotweed Flute Dan Ty Ba Bodhran Shakuhachi Gopichand Hang Drum Chanchiki Jaw Harps Chu-daiko Europe: Rattle Cog Daibyoshi Double Flute Hira-Daiko Dvojnice Double Flute Latin America: Hyoushigi Double Flute Drone Andean Panpipes Ko-Daiko -

Master in Performing Arts

1 THE COURSE – CURRICULUM FOR MASTER OF PERFORMING ARTS (MPA) DANCE & DRAMA (DNC & DRM) 2010 - 2012 SAMBALPUR UNIVERSITY 2 SCHOOL OF PERFORMING ARTS Courses Offered : (1) Master of Performing Arts, Dance (MPA-DNC) (2) Master of Performing Arts, Drama (MPA-DRM) Aim and Objective : The above courses aim at providing both theoretical and practical aspects of dance/drama to students and facilitating them to take up career in performing art. Duration : Two years Pattern : Semester-cum-Course Credit System Total Mark : 1000 Credit Hours : 80 CH Seat : 16 + 16 Outline of the Course Curriculum for MPA (DNC) Specializations : Dance: (A) Bharat Natyam (B) Odissi (C) Sambalpur (D) The Chhau 1ST SEMESTER MPA (DNC) – 4.1.1 : History of Indian Dance and Drama (Ancient and Medieval) (4CH) MPA (DNC) – 4.1.2 : Natyashastra and Other Texts (4 CH) MPA (DNC) – 4.1.3 : Regional Dance and Drama Traditions of Western Odisha (4CH) MPA (DNC) – 4.1.4 : Studio Course-I (Yoga, Exercise and Body fitness) (2 CH) MPA (DNC) – 4.1.5 : Studio Course – II (Music) (2 CH) MPA (DNC) – 4.1.6 : Studio Course-III (Multimedia and Computer-General) (4 CH) 2ND SEMESTER MPA (DNC) – 4.2.1 : Indian Dance : Pre and Post-Independence Scenario (4CH) MPA (DNC) – 4.2.2 : Dance Aesthetics (4 CH) MPA (DNC) – 4.2.3 : Popular Dances of the World (4CH) MPA (DNC) – 4.2.4 : Studio Course-IV (Abhinaya Aspect of Classical) (4 CH) MPA (DNC) – 4.2.5 : Studio Course – V (Rhythm) (4 CH) 3 3RD SEMESTER MPA (DNC) – 5.1.1 : Contemporary Indian Dance Scenario ( 4 CH) MPA (DNC) – 5.1.2 : Studio Course-VI -

Sagarmathako(English)… Final

Dancing Soul of Mount Everest Creator & Creation (Selected Modern Nepali Poems) Editing Advisors Dr. Govinda Raj Bhattarai Rajeshwor Karki Proposer Dr. Laxman Prasad Gautam Editor Momila Translator & Language Editor Mahesh Paudyal Publisher Nepali Kalasahitya Dot Com Pratishthan [Nepali Art & Literature Dot Com Foundation] (Under the project of Nepal Academy) Dancing Soul of Mount Everest Creator & Creation (Selected Modern Nepali Poems) Editor : Momila Translator & Language Editor : Mahesh Paudyal Publisher : Nepali Kalasahitya Dot Com Pratishthan (Nepali Art & Literature Dot Com Foundation) ©:Publisher Edition : First, 2011 Copies : 1001 Cover Design : Graphic Workshop Layout : Jeevan Nepal Printer : Modern Printing Press Kantipath, Kathmandu, Phone: 4253195 Price : NRs. 1,200.00 IRs. 1,000.00 US$ 25.00 Euro 20.00 ISBN: 978-9937-2-3657-7 DANCING SOUL OF MOUNT EVEREST (an anthology of selected modern Nepali poems) Editorial Context Heart-Transfer/Moksha Esteemed Readers! Here in editorial context, I extend words of gratitude that express themselves, though they might have remained apparently unexpressed. All of your accepted / unaccepted self-reflections shall become collages on the canvas of the history assimilated in this anthology. Dear Feelers! Wherever and whenever questions evolve, the existential consciousness of man keeps exploring the horizon of possibilities for the right answer even without the ultimate support to fall back upon. Existential revelations clearly dwell on the borderline, though it might be in a clash. In the present contexts, at places, questions of Nepali identity, modernity, representativeness, poetic quality, mainstream or periphery, temporal boundaries and limitations of number evolve – wanted or unwanted. Amidst the multitude of these questions, Dancing Soul of Mount Everest has assumed this accomplished form in its attempt to pervade the entirety as far as possible.