Aberystwyth University a Rural Vision for Wales

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Audit of Regional Working

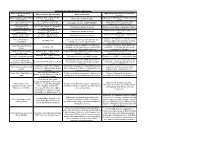

Audit of Regional Working - Place Directorate Name of Regional Group / What are the Benefits to CCoS of this Which Partners are involved? What is the remit? Working Group? Swansea Bay City Deal Officer Swansea, NPT, Carms, Pembs, Significant investment, job creation, economic Deliver the City Deal Projcets Working Group Ceredigion, Powys growth RDP South West & Central NPT, Swansea, Carmarthen, awareness of activity, delivery, risks, Information exchange of RDP LEADER Local Action Group Pembrokeshire, Ceredigion, Powys evaluation and expansion of RDP Workways + ESF NPT (lead), Swansea, Carmarthen, Management groups for project Management of major employability initiative employability project Pembs, Ceredigion Cynydd ESF young people Pembs (Lead), Swansea, Management of major youth engagement Management groups for project support project Carmarthen, NPT, Ceredigion project Cam Nesa ESF NEETs Pembs (Lead), Swansea, Management of major NEET engagement Management groups for project Employability Project Carmarthen, NPT, Ceredigion project Contibute to development of new WG Valleys Valleys Task Force - to develop each concept outlined in the “Our All Valleys LA's strategy; could be linked to future funding Landscapes Valleys, Our Future” high level plan opporutnities for north Swansea Meeting of officers engaged in securing and Exchange of information and good practice, Welsh European Funding All Wales LA's managing external funding sources such as EU constructive networking with other Local Group funding, HLF, WG capital funding etc authorities, -

Women in the Rural Society of South-West Wales, C.1780-1870

_________________________________________________________________________Swansea University E-Theses Women in the rural society of south-west Wales, c.1780-1870. Thomas, Wilma R How to cite: _________________________________________________________________________ Thomas, Wilma R (2003) Women in the rural society of south-west Wales, c.1780-1870.. thesis, Swansea University. http://cronfa.swan.ac.uk/Record/cronfa42585 Use policy: _________________________________________________________________________ This item is brought to you by Swansea University. Any person downloading material is agreeing to abide by the terms of the repository licence: copies of full text items may be used or reproduced in any format or medium, without prior permission for personal research or study, educational or non-commercial purposes only. The copyright for any work remains with the original author unless otherwise specified. The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder. Permission for multiple reproductions should be obtained from the original author. Authors are personally responsible for adhering to copyright and publisher restrictions when uploading content to the repository. Please link to the metadata record in the Swansea University repository, Cronfa (link given in the citation reference above.) http://www.swansea.ac.uk/library/researchsupport/ris-support/ Women in the Rural Society of south-west Wales, c.1780-1870 Wilma R. Thomas Submitted to the University of Wales in fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy of History University of Wales Swansea 2003 ProQuest Number: 10805343 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

News Briefing ΠAugust 2010

North Pembrokeshire Transport Forum Fforwm Trafnidiaeth Gogledd Penfro News Briefing – September 2010 Buses TrawsCambria Network Consultation. The TrawsCambria bus network provides an essential public transport link between key centres. The network is designed to connect into the rail network at key stations such as Carmarthen, Aberystwyth, Wrexham and Bangor. This consultation, which closes on 12th December, is seeking views about TrawsCambria’s plans to improve the network. Potential improvements include: · Reduced journey times between key centres by public transport · Better connections between TrawsCambria services and the rail network in Wales · Potential new services to provide a wider range of choice when travelling between key centres across Wales · The introduction of new more comfortable coach style vehicles which are better suited to longer distance services · Improved “on board” facilities for passengers · Improved ticketing and fare options Further information about the consultation, including the consultation questionnaire, can be found on: http://wales.gov.uk/consultations/transport/trawscambria/?lang=en. Bouquet for Pembrokeshire Bus Drivers: A regular bus passenger has reported to the Forum’s Executive Committee: “Travelling on an extremely wet Wednesday I was impressed with how helpful the bus drivers were, taking passenger as close to their destinations as possible. It’s what rural bus services are all about, with real people drivers. First, Silcox and Richard Brothers are to be commended”. Community Transport Preseli Green Dragon. Organisers report that their summer services have been well received this year. The new Gwaun Valley service, from Fishguard to Bwlchgwynt, is very popular. They have resumed running the Sunday evening service to Theatre Mwldan in Cardigan. -

Directory of Cancer Support Services in South West Wales. 2010-2011

Directory of Cancer Support Services in South West Wales. 2010-2011 Self Help and Support Groups Voluntary Sector Hospice and Palliative Care Providers South West Wales Cancer Network 2010 Prepared by Helen Dorman, Macmillan Patient Involvement Facilitator SOUTH WEST WALES CANCER NETWORK SELF HELP / SUPPORT GROUPS NAME & ADDRESS INFORMATION TELEPHONE NUMBER The Beacon of Hope. A small team of professionals Aberystwyth. and volunteers working for 01970 615593 Cardigan a charity; providing immediate 01239 614989 comfort and on-going practical support to people with a life limiting or terminal illness in Ceredigion Pembrokeshire Meetings held on the2nd 01437 710376 Breast Cancer Friday of every month, 01437 720496 Support Group. between 10:30-12:30 The Community Providing support for those Centre, diagnosed with breast cancer Furzy Park, in Pembrokeshire Haverfordwest Tawe Valley Breast Support and Information. 01158 822554 Care Support Group. Secretary, Mair Griffith 01558 822588 Pembrokeshire Registered Charity. Barbara/ Jill Cancer Support. Provides Support &Information 01646 683078 for those who have or have had cancer together with their family and friends . Llanelli Breast Meet every 3 rd . Monday of the Jean 01554 Cancer Support month except in August. 810967 Group Provides support and Dilys (Welsh friendship. Speaker) 01554 758413 Breast Cancer Care. Support and advice Valerie Carmarthen Pearson 01559 384854 Stepping Stones A support group for women Angela Hamer Breast Support who meet in conjunction with 01686 624702 Group Macmillan Nurses, every Ist. Mary Newtown, Mid Wednesday of the month at 01938 558047 Powys 19:00 at The Hafan Day Unit, Newtown Hospital NAME & ADDRESS INFORMATION TELEPHONE NUMBER Breast of Friends Support and Information Janet Williams Breast Support 01686 412778 Group Llanidloes, Mid Powys Breast Cancer Information and advice Ffion Davies Group Community The Black Mountain Developmental Centre, Officer Cwmgarw Road, Brynaman 01269 823400 Carmarthenshire Llandeilo Breast Information and support Diane Rocca Cancer Group. -

NORTH WALES Expenditure £'S Scheme Local Authority Type Scheme Name 2011 to Date Future Total

NORTH WALES Expenditure £'s Scheme Local Authority Type Scheme Name 2011 to date Future Total Anglesey Local Llangefni Link Road 365,000 0 365,000 Trunk Britannia Bridge 300,000 0 300,000 Anglesey / Local Surface Access – Anglesey Airport 158,000 0 158,000 Gwynedd Trunk A55 Britannia Bridge 40,000 0 40,000 -A470 Pont yr Afanc, A5 Sth of Cerrigydrudion, A55 rainbow bridge, A5 W Hendre Arddwyfaen, E27A55 Conwy Trunk Tunnels safety improvement 18,845,000 32,500,000 51,345,000 Trunk A55 Junctions 15 and 16 Improvements 10,000 31,600,000 31,610,000 -A55 Talardy Para Refurb,A494 maesgarnedd Jctn, Denbighshire Trunk A5 Llangollen Golf Club, A494 Ruthin Vale 216,000 0 216,000 Trunk A5 Pont Melin Rug 165,000 0 165,000 Local Foryd Rd Junction Improvements 160,000 0 160,000 Flintshire Trunk A494/A550 Deeside Park to Drome Corner 90,000 206,270,000 206,360,000 Trunk -A55 J29 to 21, A55 Refuge/Crossovers 4,300,000 0 4,300,000 Local Shotton Corridor Signalisation B5129 450,000 0 450,000 Trunk A494 Drome Corner to Ewloe 44,000 0 44,000 Gwynedd Trunk A487 Caernarfon to Bontnewydd 921,000 103,927,000 104,847,000 Trunk A487 Dyfi Bridge 65,000 22,880,000 22,945,000 Trunk A487 Porthmadog, Minffordd and Tremadog 15,694,000 446,000 16,140,000 Trunk A470 Maes yr Helmau – Cross Foxes 10,123,000 472,000 10,595,000 Trunk A470 Gelligemlyn 9,185,000 176,000 9,361,000 - Pont Briwet, A493 Pontbren to Nant y Gwenlli, Local -A487Pont Dr Garndolbenmaen, Williams School, A494Dolgellau Golwg Hir, 3,757,000 0 3,757,000 Dolgellau, A487 Golan Junction, A55 Aber Tai’r Trunk -

South West Wales Regional Report

SOUTH WEST WALES REGIONAL COMMITTEE REPORT TO THE NATIONAL ASSEMBLY FOR WALES, 2003 - 2004 Introduction 1. The South West Wales Regional Committee is one of the Assembly's four regional committees constituted under s61 of the Government of Wales Act 1998 and Standing Order 10. 2. Standing Order 10.2 provides that “Regional committees shall advise the Assembly on matters affecting their regions, the affect of Assembly policies in those regions and the work of public bodies there.” The Committee is required to meet at least twice a year in the region. 3. There are 17 members: Peter Black South Wales West Liberal Democrats Nicholas Bourne Mid and West Wales Conservative Alun Cairns South Wales West Conservative Andrew Davies Swansea West Labour Glyn Davies Mid and West Wale Conservative Janet Davies South Wales West Plaid Cymru Tamsin Dunwoody Preseli Pembrokeshire Labour Kneafsey Lisa Francis Mid and West Wales Conservative Brian Gibbons Aberavon Labour Christine Gwyther Carmarthen West and Labour South Pembrokeshire Edwina Hart Gower Labour Helen Mary Jones Mid and West Wales Plaid Cymru Dai Lloyd South Wales West Plaid Cymru Val Lloyd Swansea East Labour Catherine Thomas Llanelli Labour Gwenda Thomas Neath Labour Rhodri Glyn Thomas Carmarthen East and Plaid Cymru Dinefwr 4. Peter Black was elected to chair the Committee from July 2003. Meetings 5. The Committee met five times between July 2003 and March 2004. Method of working 6. Generally, the Committee has focused on public discussion of policies being developed by the Welsh Assembly Government or reviews being carried out by subject committees. Members of the public have been able to raise questions and express their views on the topics discussed. -

Development of a Mid and South West Wales Regional Centre Of

Name of Meeting Board Date of Meeting 28 March 2019 Agenda item: 9.2.280319 Development of a Mid and South West Wales Regional Centre of Excellence Cellular Pathology Laboratory, Regional Diagnostic Immunology Laboratory & Regional Medical Microbiology Facility at Morriston Hospital, Swansea Executive lead: Dr Quentin Sandifer, Executive Director of Public Health Services and Medical Director Author: Ms Heather Edwards, Business Planning Manager, Abertawe Bro Morgannwg University Health Board, with amendment where necessary by Dr Quentin Sandifer, Executive Director of Public Health Services and Medical Director Approval/Scrutiny Business Executive Team, 18 March 2019 route: Purpose To seek Board approval on the Strategic Outline Case (SOC) prior to submission to Welsh Government. Nationally NHS Pathology services face a number of challenges. Within the Mid and South West Wales’ region, Hywel Dda University Health Board (HDUHB), Abertawe Bro Morgannwg University Health Board (ABMUHB) and Public Health Wales NHS Trust (PHW) are struggling to manage workforce and sustainability pressures, to maintain quality and safety issues and to meet clinically driven targets. Without investment in sustainable services we cannot deliver essential improvements and fit for purpose laboratories. Investment would allow us to co-locate and develop regionalised services and to support more innovative and sustainable service models which could be future-proofed, and be flexible enough, to respond to changing demand, new technologies and innovations. In 2017 a South West Wales Regional Pathology Reconfiguration Project Board was established to draft a Strategic Outline Business Case (SOC) to address these regional challenges in line with the national direction of travel for regional pathology services. -

Future Need and Demand for Housing in Wales

Future Need and Demand for Housing in Wales September 2015 Future Need and Demand for Housing in Wales Alan E. Holmans Cambridge Centre for Housing and Planning Research This report and the information contained within it are the copyright of the Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO, and are licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3. The views expressed are the author’s and do not necessarily reflect those of the Institute’s Executive Group or Board of Governors. Alan Holmans was acknowledged as the UK’s preeminent expert in projecting future housing need and demand. He conducted the analysis presented in this report shortly before his death in March 2015. Researchers from the Public Policy Institute for Wales edited Alan’s draft submission in order to bring it to publication but the analysis and key findings are his. For further information please contact: Dan Bristow Public Policy Institute for Wales Tel: 029 2087 5345 Email: [email protected] Contents Summary .............................................................................................................................. 1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 2 Methodology ......................................................................................................................... 2 Estimating Total Need and Demand ..................................................................................... -

Written Questions Answered Between 8 and 15 March 2007

Written Questions answered between 8 and 15 March 2007 [R] signifies that the Member has declared an interest. [W] signifies that the question was tabled in Welsh. Contents Questions to the First Minister Questions to the Minister for Culture, Welsh Language and Sport Questions to the Minister for Enterprise, Innovation and Networks Questions to the Minister for Education, Lifelong Learning Skills Questions to the Finance Minister Questions to the Minister for Health and Social Services Questions to the Minister for Social Justice and Regeneration Questions to the First Minister Jonathan Morgan: Will the First Minister make a statement on the number and cost of civil servants employed by the Welsh Assembly Government? (WAQ47069) Substantive answer following holding reply. The First Minister (Rhodri Morgan): The Permanent Secretary has supplied the following answer: As Assembly Government staffing is my responsibility the First Minister has asked me to write to you on these matters. I wrote to you separately in December 2005 and January 2006 in response to a number of written Assembly questions (WAQ44881, WAQ44882, WAQ44869 and WAQ44883) tabled for the First Minister about the numbers of Assembly staff, the costs of administration and the salary bill of civil servants. In my responses (attached for your information) I provided you with details of staff numbers and costs from the inception of the Assembly as requested. The increases in staff numbers and associated costs have occurred as the Government has taken on responsibility for a broad range of functions either new or previously external to the Assembly. These include the transfer of: 2000-01 197 staff from WHCSA, Health Promotion Wales, WORD, WEPE and Wales Trade International. -

City and County of Swansea Dinas a Sir Abertawe And

CITY AND COUNTY OF SWANSEA DINAS A SIR ABERTAWE AND NEATH PORT TALBOT COUNTY BOROUGH COUNCIL CYNGOR BWRDEISTREF SIROL CASTELL-NEDD PORT TALBOT Report of the County Archivist West Glamorgan Archives Committee 18 September 2015 The purpose of this report is to outline the work of the Archive Service during the period June to August 2015 1. South West Wales Partnership A further meeting took place on 20 th July between Swansea University and Swansea, Neath Port Talbot and Carmarthenshire Councils to explore the development together of shared archive provision for south west Wales. The outcome of the meeting was the statement which is attached at Appendix 1, drafted with the aid of archival consultant Elizabeth Oxborrow-Cowan. Each partner in the group is seeking approval for this statement from its governing committee and (in the case of West Glamorgan Archive Service) from each of its parent authorities. Members are requested to approve the use of Archive Service reserves to make the appropriate contribution towards consultancy fees to further investigate joint service options with Swansea University and Carmarthenshire County Council. It is anticipated that a one-third share will cost the Service approximately £5,000. 2. Use of the Service Statistics for June to August 2015 The number of members of public using the Service on-site, June to August 2015, was 1,927 and the total number reached by the Service on and off-site was 2,188 . Number of on-site visits at Swansea, Neath and Port Talbot 1,927 (1,907) (figures in brackets represent -

National Transport Plan March 2010 G/MH/3531/02-10 February Typeset in 12Pt ISBN 978 0 7504 5494 0 CMK-22-03-220 © Crown Copyright 2010 Contents

www.wales.gov.uk National Transport Plan March 2010 G/MH/3531/02-10 February Typeset in 12pt ISBN 978 0 7504 5494 0 CMK-22-03-220 © Crown copyright 2010 Contents Contents Foreword 2 Summary 3 Chapter 1 – Introduction 9 1.1 The role of the National Transport Plan 9 1.2 Reducing carbon equivalent emissions from transport 9 1.3 Delivering the National Transport Plan: All-Wales and strategic corridors 10 1.4 Developing solutions to transport issues 11 1.5 Funding the National Transport Plan 11 1.6 Monitoring 11 Chapter 2 – Transport across Wales 13 2.1 Sustainable travel centres 13 2.2 Integrating the impact of travel into wider decision making 13 2.3 Increasing healthy and sustainable travel choices, including walking and cycling 14 2.4 Improving local bus services 15 2.5 Improving rail services 16 2.6 Improving access to key sites and services 17 2.7 Managing our road infrastructure 18 2.8 Improving the safety of the road network 18 2.9 Improving the sustainability of freight transport 19 2.10 Improving the sustainability of transport infrastructure and reducing environmental effects 20 Chapter 3 – The north-south corridor 23 3.1 Targeted investment in infrastructure 23 3.2 North-south air service 25 Chapter 4 – The east-west corridor in south Wales 27 4.1 Targeted investment in infrastructure 27 4.2 Targeted proposals for south-east Wales 29 Chapter 5 – The east-west corridor in north Wales 31 5.1 Targeted investment in infrastructure 31 5.2 Targeted proposals for north-east Wales 32 Chapter 6 – The east-west corridor in mid-Wales 33 6.1 Targeted investment in infrastructure 33 Chapter 7 – Beyond 2015 35 Chapter 8 – Assessment and appraisal 37 1 National Transport Plan Foreword Foreword How people move about and transport goods is central to our economy and our way of life. -

FOLK-LORE and FOLK-STORIES of WALES the HISTORY of PEMBROKESHIRE by the Rev

i G-R so I FOLK-LORE AND FOLK-STORIES OF WALES THE HISTORY OF PEMBROKESHIRE By the Rev. JAMES PHILLIPS Demy 8vo», Cloth Gilt, Z2l6 net {by post i2(ii), Pembrokeshire, compared with some of the counties of Wales, has been fortunate in having a very considerable published literature, but as yet no history in moderate compass at a popular price has been issued. The present work will supply the need that has long been felt. WEST IRISH FOLK- TALES S> ROMANCES COLLECTED AND TRANSLATED, WITH AN INTRODUCTION By WILLIAM LARMINIE Crown 8vo., Roxburgh Gilt, lojC net (by post 10(1j). Cloth Gilt,3l6 net {by posi 3lio% In this work the tales were all written down in Irish, word for word, from the dictation of the narrators, whose name^ and localities are in every case given. The translation is closely literal. It is hoped' it will satisfy the most rigid requirements of the scientific Folk-lorist. INDIAN FOLK-TALES BEING SIDELIGHTS ON VILLAGE LIFE IN BILASPORE, CENTRAL PROVINCES By E. M. GORDON Second Edition, rez'ised. Cloth, 1/6 net (by post 1/9). " The Literary World says : A valuable contribution to Indian folk-lore. The volume is full of folk-lore and quaint and curious knowledge, and there is not a superfluous word in it." THE ANTIQUARY AN ILLUSTRATED MAGAZINE DEVOTED TO THE STUDY OF THE PAST Edited by G. L. APPERSON, I.S.O. Price 6d, Monthly. 6/- per annum postfree, specimen copy sent post free, td. London : Elliot Stock, 62, Paternoster Row, E.C. FOLK-LORE AND FOLK- STORIES OF WALES BY MARIE TREVELYAN Author of "Glimpses of Welsh Life and Character," " From Snowdon to the Sea," " The Land of Arthur," *' Britain's Greatness Foretold," &c.