Gertrude Stein's Differential Syntax

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Humble Protest a Literary Generation's Quest for The

A HUMBLE PROTEST A LITERARY GENERATION’S QUEST FOR THE HEROIC SELF, 1917 – 1930 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Jason A. Powell, M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2008 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Steven Conn, Adviser Professor Paula Baker Professor David Steigerwald _____________________ Adviser Professor George Cotkin History Graduate Program Copyright by Jason Powell 2008 ABSTRACT Through the life and works of novelist John Dos Passos this project reexamines the inter-war cultural phenomenon that we call the Lost Generation. The Great War had destroyed traditional models of heroism for twenties intellectuals such as Ernest Hemingway, Edmund Wilson, Malcolm Cowley, E. E. Cummings, Hart Crane, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and John Dos Passos, compelling them to create a new understanding of what I call the “heroic self.” Through a modernist, experience based, epistemology these writers deemed that the relationship between the heroic individual and the world consisted of a dialectical tension between irony and romance. The ironic interpretation, the view that the world is an antagonistic force out to suppress individual vitality, drove these intellectuals to adopt the Freudian conception of heroism as a revolt against social oppression. The Lost Generation rebelled against these pernicious forces which they believed existed in the forms of militarism, patriotism, progressivism, and absolutism. The -

The Radical Ekphrasis of Gertrude Stein's Tender Buttons Georgia Googer University of Vermont

University of Vermont ScholarWorks @ UVM Graduate College Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 2018 The Radical Ekphrasis Of Gertrude Stein's Tender Buttons Georgia Googer University of Vermont Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/graddis Recommended Citation Googer, Georgia, "The Radical Ekphrasis Of Gertrude Stein's Tender Buttons" (2018). Graduate College Dissertations and Theses. 889. https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/graddis/889 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks @ UVM. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate College Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ UVM. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE RADICAL EKPHRASIS OF GERTRUDE STEIN’S TENDER BUTTONS A Thesis Presented by Georgia Googer to The Faculty of the Graduate College of The University of Vermont In Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts Specializing in English May, 2018 Defense Date: March 21, 2018 Thesis Examination Committee: Mary Louise Kete, Ph.D., Advisor Melanie S. Gustafson, Ph.D., Chairperson Eric R. Lindstrom, Ph.D. Cynthia J. Forehand, Ph.D., Dean of the Graduate College ABSTRACT This thesis offers a reading of Gertrude Stein’s 1914 prose poetry collection, Tender Buttons, as a radical experiment in ekphrasis. A project that began with an examination of the avant-garde imagism movement in the early twentieth century, this thesis notes how Stein’s work differs from her Imagist contemporaries through an exploration of material spaces and objects as immersive sensory experiences. This thesis draws on late twentieth century attempts to understand and define ekphrastic poetry before turning to Tender Buttons. -

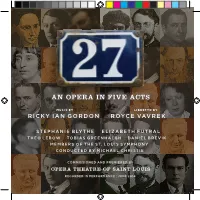

An Opera in Five Acts

AN OPERA IN FIVE ACTS MUSIC BY LIBRETTO BY RICKY IAN GORDON ROYCE VAVREK STEPHANIE BLYTHE ELIZABETH FUTRAL THEO LEBOW TOBIAS GREENHALGH DANIEL BREVIK MEMBERS OF THE ST. LOUIS SYMPHONY CONDUCTED BY MICHAEL CHRISTIE COMMISSIONED AND PREMIERED BY OPERA THEATRE OF SAINT LOUIS RECORDED IN PERFORMANCE : JUNE 2014 1 CD 1 1) PROLOGUE | ALICE KNITS THE WORLD [5:35] ACT ONE 2) SCENE 1 — 27 RUE DE FLEURUS [10:12] ALICE B. TOKLAS 3) SCENE 2 — GERTRUDE SITS FOR PABLO [5:25] AND GERTRUDE 4) SCENE 3 — BACK AT THE SALON [15:58] STEIN, 1922. ACT TWO | ZEPPELINS PHOTO BY MAN RAY. 5) SCENE 1 — CHATTER [5:21] 6) SCENE 2 — DOUGHBOY [4:13] SAN FRANCISCO ACT THREE | GÉNÉRATION PERDUE MUSEUM OF 7) INTRODUCTION; “LOST BOYS” [5:26] MODERN ART. 8) “COME MEET MAN RAY” [5:48] 9) “HOW WOULD YOU CHOOSE?” [4:59] 10) “HE’S GONE, LOVEY” [2:30] CD 2 ACT FOUR | GERTRUDE STEIN IS SAFE, SAFE 1) INTRODUCTION; “TWICE DENYING A WAR” [7:36] 2) “JURY OF MY CANVAS” [6:07] ACT FIVE | ALICE ALONE 3) INTRODUCTION; “THERE ONCE LIVED TWO WOMEN” [8:40] 4) “I’VE BEEN CALLED MANY THINGS" [8:21] 2 If a magpie in the sky on the sky can not cry if the pigeon on the grass alas can alas and to pass the pigeon on the grass alas and the magpie in the sky on the sky and to try and to try alas on the grass the pigeon on the grass and alas. They might be very well very well very ALICE B. -

A Critical Study of the Loss and Gain of the Lost Generation

Opción, Año 34, Especial No.15 (2018): 1436-1463 ISSN 1012-1587/ISSNe: 2477-9385 A Critical Study of the Loss and Gain of the Lost Generation Seyedeh Zahra Nozen1 1Department of English, Amin Police Science University [email protected] Shahriar Choubdar (MA) Malayer University, Malayer, Iran [email protected] Abstract This study aims to the evaluation of the features of the group of writers who chose Paris as their new home to produce their works and the overall dominant atmosphere in that specific time in the generation that has already experienced war through comparative research methods. As a result, writers of this group tried to find new approaches to report different contexts of modern life. As a conclusion, regardless of every member of the lost generation bohemian and wild lifestyles, the range, creativity, and influence of works produced by this community of American expatriates in Paris are remarkable. Key words: Lost Generation, World War, Disillusionment. Recibido: 04-12--2017 Aceptado: 10-03-2018 1437 Zahra Nozen and Shahriar Choubdar Opción, Año 34, Especial No.15(2018):1436-1463 Un estudio crítico de la pérdida y ganancia de la generación perdida Resumen Este estudio tiene como objetivo la evaluación de las características del grupo de escritores que eligieron París como su nuevo hogar para producir sus obras y la atmósfera dominante en ese momento específico en la generación que ya ha experimentado la guerra a través de métodos de investigación comparativos. Como resultado, los escritores de este grupo trataron de encontrar nuevos enfoques para informar diferentes contextos de la vida moderna. -

University of Alberta

University of Alberta Gertrude Stein’s Cubist Brain Maps by Lorelee Kim Kippen A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Comparative Literature ©Lorelee Kim Kippen Fall 2009 Edmonton, Alberta Permission is hereby granted to the University of Alberta Libraries to reproduce single copies of this thesis and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research purposes only. Where the thesis is converted to, or otherwise made available in digital form, the University of Alberta will advise potential users of the thesis of these terms. The author reserves all other publication and other rights in association with the copyright in the thesis and, except as herein before provided, neither the thesis nor any substantial portion thereof may be printed or otherwise reproduced in any material form whatsoever without the author's prior written permission. Library and Archives Bibliothèque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l’édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-53987-3 Our file Notre référence ISBN:978-0-494-53987-3 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L’auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l’Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. -

A Discord to Be Listened for in Gertrude Stein and Virginia Woolf

Trinity College Trinity College Digital Repository Senior Theses and Projects Student Scholarship Spring 2018 A Discord to be Listened For in Gertrude Stein and Virginia Woolf Sophie Prince Trinity College, Hartford Connecticut, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Prince, Sophie, "A Discord to be Listened For in Gertrude Stein and Virginia Woolf". Senior Theses, Trinity College, Hartford, CT 2018. Trinity College Digital Repository, https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses/713 TRINITY COLLEGE Senior Thesis / A DISCORD TO BE LISTENED FOR / IN GERTRUDE STEIN AND VIRGINIA WOOLF submitted by SOPHIE A. PRINCE, CLASS OF 2018 In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts 2018 Director: David Rosen Reader: Katherine Bergren Reader: James Prakash Younger Table of Contents Acknowledgments…………………………………………………………...………….………....i Introduction……………………………………………………………..…………………..……..ii Chapter 1: Narratives of Consciousness………..……………………………………………........1 Modern Theories of Mind Percussive Rhythms in “Melanctha” Alliterative Melodies in Mrs. Dalloway The Discontents of Narrative Chapter 2: Abstracting the Consciousness……………………………..…………………..…….57 The Consciousness Machine of Tender Buttons The Almost Senseless Song of The Waves Works Cited…………………………………………………...………………….…………….107 i Acknowledgments First, to my many support systems. My thesis colloquium, my dear roommates, and, of course, my family. I could not have accomplished this without them. To the English Department at Trinity College: especially Barbara Benedict, who convinced me to study literature and advised me for my first years here, Katherine Bergren, who has pushed my writing to be better and assigned Tender Buttons in a survey class one fateful day, and Sarah Bilston, for fearlessly leading our thesis colloquium. -

A Discord to Be Listened for in Gertrude Stein and Virginia Woolf Sophie Prince Trinity College, Hartford Connecticut, [email protected]

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Trinity College Trinity College Trinity College Digital Repository Senior Theses and Projects Student Works Spring 2018 A Discord to be Listened For in Gertrude Stein and Virginia Woolf Sophie Prince Trinity College, Hartford Connecticut, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Prince, Sophie, "A Discord to be Listened For in Gertrude Stein and Virginia Woolf". Senior Theses, Trinity College, Hartford, CT 2018. Trinity College Digital Repository, https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses/713 TRINITY COLLEGE Senior Thesis / A DISCORD TO BE LISTENED FOR / IN GERTRUDE STEIN AND VIRGINIA WOOLF submitted by SOPHIE A. PRINCE, CLASS OF 2018 In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts 2018 Director: David Rosen Reader: Katherine Bergren Reader: James Prakash Younger Table of Contents Acknowledgments…………………………………………………………...………….………....i Introduction……………………………………………………………..…………………..……..ii Chapter 1: Narratives of Consciousness………..……………………………………………........1 Modern Theories of Mind Percussive Rhythms in “Melanctha” Alliterative Melodies in Mrs. Dalloway The Discontents of Narrative Chapter 2: Abstracting the Consciousness……………………………..…………………..…….57 The Consciousness Machine of Tender Buttons The Almost Senseless Song of The Waves Works Cited…………………………………………………...………………….…………….107 i Acknowledgments First, to my many support systems. My thesis colloquium, my dear roommates, and, of course, my family. I could not have accomplished this without them. To the English Department at Trinity College: especially Barbara Benedict, who convinced me to study literature and advised me for my first years here, Katherine Bergren, who has pushed my writing to be better and assigned Tender Buttons in a survey class one fateful day, and Sarah Bilston, for fearlessly leading our thesis colloquium. -

American Modernist Writers: How They Touched the Private Realm of Life Leyna Ragsdale Summer II 2006

American Modernist Writers: How They Touched the Private Realm of Life Leyna Ragsdale Summer II 2006 Introduction The issue of personal identity is one which has driven American writers to create a body of literature that not only strives to define the limitations of human capacity, but also makes a lasting contribution in redefining gender roles and stretching the bounds of freedom. A combination of several historical aspects leading up to and during the early 20th century such as Women's Suffrage and the Great War caused an uprooting of the traditional moral values held by both men and women and provoked artists to create a new American identity through modern art and literature. Gertrude Stein used her writing as a tool to express new outlooks on human sexuality and as a way to educate the public on the repression of women in order to provoke changes in society. Being a pupil of Stein's, Ernest Hemingway followed her lead in the modernist era and focused his stories on human behavior in order to educate society on the changes of gender roles and the consequences of these changes. Being a man, Hemingway focused more closely on the way that men's roles were changing while Stein focused on women's roles. However, both of these phenomenal early 20th century modernist writers made a lasting impact on post WWI America and helped to further along the inevitable change from the unrealistic Victorian idea of proper conduct and gender roles to the new modern American society. The Roles of Men and Women The United States is a country that has been reluctant to give equal rights to women and has pushed them into subservient roles. -

Everybody's Story: Gertrude Stein's Career As a Nexus

EVERYBODY’S STORY: GERTRUDE STEIN’S CAREER AS A NEXUS CONNECTING WRITERS AND PAINTERS IN BOHEMIAN PARIS By Elizabeth Frances Milam A thesis submitted to the faculty of the University of Mississippi in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Sally Barksdale Honors College Oxford, May 2017 Approved by: _______________________________________ Advisor: Professor Elizabeth Spencer _______________________________________ Reader: Professor Matt Bondurant ______________________________________ Reader: Professor John Samonds i ©2017 Elizabeth Frances Milam ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT ELIZABETH FRANCES MILAM: EVERYBODY’S STORY: GERTRUDE STEIN’S CAREER AS A NEXUS CONNECTING WRITERS AND PAINTERS IN BOHEMIAN PARIS Advisor: Elizabeth Spencer My thesis seeks to question how the combination of Gertrude Stein, Paris, and the time period before, during, and after The Great War conflated to create the Lost Generation and affected the work of Sherwood Anderson and Ernest Hemingway. Five different sections focus on: the background of Stein and how her understanding of expression came into existence, Paris and the unique environment it provided for experimentation at the beginning of the twentieth century (and how that compared to the environment found in America), Modernism existing in Paris prior to World War One, the mass culture of militarization in World War One and the effect on the subjective perspective, and post-war Paris, Stein, and the Lost Generation. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION………………………………………………………………v-vi CHAPTER ONE: STEIN’S FORMATIVE YEARS…………………………..vii-xiv CHAPTER TWO: EARLY TWENTIETH CENTURY PARIS……..………...xv-xxvi CHAPTER THREE: PREWAR MODERNISM.........………………………...xxvii-xl CHAPTER FOUR: WORLD WAR ONE…….......…………..…………..……...xl-liii CHAPTER FIVE: POST WAR PARIS, STEIN, AND MODERNISM ……liii-lxxiv CONCLUSION…………………………………………………………....lxxv-lxxvii BIBLIOGRAPHY……………………………………………………….lxxviii-lxxxiii iv INTRODUCTION: The destruction caused by The Great War left behind a gaping chasm between the pre-war worldview and the dark reality left after the war. -

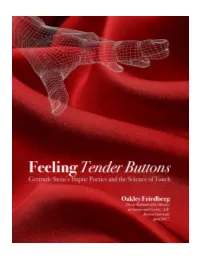

Tender Buttons Gertrude Stein’S Haptic Poetics and the Science of Touch

Feeling Tender Buttons Gertrude Stein’s Haptic Poetics and the Science of Touch Oakley Dean Friedberg Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts with Honors in Science and Society Brown University April 2017 Primary Advisor: Ada Smailbegović, Ph.D. Second Reader: William Warren, Ph.D. Acknowledgments I would like to thank my advisor, Professor Ada Smailbegović, for helping me learn how to map out a space between science and poetry. Your hand-drawn illustrations and verbal analogies to kingdoms, symphonies, sandwiches, and treasure, have been invaluable. Thank you for teaching me that I am writing for multiple types of readers, but also that I am exploring these ideas in writing for myself. Thank you to Professor William Warren for being an insightful second reader, and for sharing feedback that has deeply sharpened my conceptual framework. I am so grateful to have had this opportunity to work with you. Thank you, as well, to Louis Sass, for being an intellectual role model, and for always being so kind while helping me take my writing to the next level. I could not have done this without the support of my family, especially my mom, who has dedicated so much time and care to get me to the finish line. Thank you to my dad for always encouraging me to trust my gut, and to my sister, Lucy, for playing backgammon with me during study breaks. ii In my desiring perception I discover something like a flesh of objects. My shirt rubs against my skin, and I feel it. -

He Museum of Modern Art for RELEASE DEC

he Museum of Modern Art FOR RELEASE DEC. 9, I970 vest 33 Street, New York, N.Y. 10019 Tel. 956-6100 Cable: Modernart THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART REASSEMBLES ART COLLECTIONS OF GERTRUDE STEIN AND HER FAMILY "As I say, everybody has to like something some people like to eat, some people like to drink, some people like to make money some like to spend money, some like the theater, and some even like sculpture, some like garden ing, some like dogs, some like cats, some people like to look at things, some people like to look at everything... I have not mentioned games indoor and out, and birds and crime and politics and photography, but anybody can go on, and I, personally, I like all these things well enough but they do not hold my atten 11 tion long enough. The only thing, funnily enough, that I never get tired of doing is looking at pictures ... Presidents of the United States of America are supposed to like to look at baseball games, I can understand that, I did too once, but ultimately it did not hold my attention. Pictures made in oil on a flat surface do, they do hold my attention." This was the message Gertrude Stein, expatriate for 30 years told her audiences in 1934-35 during a triumphant lecture tour throughout her native land. She saw her name in lights in Times Square, had tea with Eleanor Roosevelt at the White House, and dined with Charlie Chaplin and Dashiel Hammett in Hollywood. Now 35 years later the pictures she talked about and which held her atten tion have been reassembled from all over the world for an exhibition that will begin a nationwide tour in December at The Museum of Modern Art in New York. -

Forming Unity in Modernity: the Use of Collage in Tender Buttons and the Waste Land Esmé Hogeveen Esmé Hogeveen Looks At

Forming Unity in Modernity: The Use of Collage in Tender Buttons and The Waste Land Esmé Hogeveen Esmé Hogeveen looks at two modernists who might well have arrived on Earth from different planets—Gertrude Stein and T.S. Eliot. While both writers struggle with how to make art from a fractured reality, Stein’s Tender Buttons addresses this at a very basic level of representation, and Eliot’s The Waste Land works at the level of cultural history. What unites them, Hogeveen persuasively argues, is their logic, the logic of collage. Eliot and Stein seem to arrive at different solutions, then, but use a single aesthetic. Or, it may well be that the aesthetic of collage is the solution. It’s not just the confusion of modernism, then, or the end point these writers reach in struggling with that confusion, but the process they go through en route. - Dr. Leonard Diepeveen In their respective poems Tender Buttons and The Waste Land , Gertrude Stein and T.S. Eliot use collage as a means to depict the decay of meaning in modern life. Stein and Eliot find the more formally cohesive aesthetics of the past unable to convey the meanings portrayed in the present, and so they turn to collage. Operating both as an aesthetic technique and as a philosophic conception, collage is able to contain the contradictions of modern life through its cut-and-paste approach to configuring appositional logic. Stein and Eliot's use of collage are not meant to confuse the reader for the sake of affirming the destabilization of meaning in the twentieth century.