Redacted for Privacy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evolution in Cultural Anthropology

UC Berkeley Anthropology Faculty Publications Title Evolution in Cultural Anthropology Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5pk146vg Journal American Anthropologist, 48(2) Author Lowie, Robert H. Publication Date 1946-06-01 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California EVOLUTION IN CULTURAL ANTHROPOLOGY: A REPLY TO LESLIE WHITE By ROBERT H. LOWIE LESLIE White's last three articles in the A merican A nthropologist1 require a reply since in my opinion they obscure vital issues. Grave matters, he clamors, are at stake. Obscurantists are plotting to defame Lewis H. Morgan and to undermine the theory of evolution. Professor White should relax. There are no underground machinations. Evolution as a scientific doctrine-not as a farrago of immature metaphysical notions-is secure. Morgan's place in the history of anthropology will turn out to be what he deserves, for, as Dr. Johnson said, no man is ever written down except by himself. These articles by White raise important questions. As a victim of his polemical shafts I should like to clarify the issues involved. I premise that I am peculiarly fitted to enter sympathetically into my critic's frame of mind, for at one time I was as devoted to Ernst Haeckel as White is to Morgan. Haeckel had solved the riddles of the universe for me. ESTIMATES OF MORGAN Considering the fate of many scientific men at the hands of their critics, it does not appear that Morgan has fared so badly. Americans bestowed on him the highest honors during his lifetime, eminent European scholars held him in esteem. -

Culturally Competent Mental Health Care for Lesbian Gay Bisexual Transgender and Questioning

COD Treatment WA State Conference Yakima, WA October 6th & 7th, 2014 Culturally Competent Mental Health Care for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Questioning (LGBTQ) Clients Donnie Goodman NCC/MA LMHP Deputy Director, Seattle Counseling Service The following are a combination of what will be covered during the 8:30 am Keynote on Tuesday, October 7th, 2014 and Workshop Session 5 from 1:45 – 3:00, Tuesday, October 7th, 2014. Part 1: Introduction to the Gay World • Introduction: • Sexual minorities are one of only two minority groups not born into their minority: . Sexual minorities . Handicapped- physical and emotional . Sexual Minorities – use of the word “Queer” • Washington State Psychological Association • Reparative/Conversion Therapy • Definitions: Common terms • Homophobia • Internalized Homophobia • Gay History • Assumptions Part 2: Life • Coming out Stages • Psychological Issues Related to Coming Out • Aspects of Coming Out • Questions to Consider When Coming Out • Coping Mechanisms for Gay Youth • Strategies for Engagement • Working With Families • Religion • Same-sex Relationships • Domestic Violence • Discussing Safe Sex: AIDS; STD’s Part 3: Therapeutic Focus and Resources • Strategies for Effective Treatment • Inclusive Language • Differential Diagnosis o PTSD o Others • Preventing/Reducing Harassment • Increasing Cultural Competence – Heterosexual Lifestyle Questionnaire • Your Organization; Your Forms/Paperwork • Resources Extra Items in the Packet • Personal Assessment of Homophobia • In-depth Description of Homophobia -

Making Gay History: the Podcast'

H-Podcast Earls on Marcus and Burningham and Rous et al., 'Making Gay History: The Podcast' Review published on Monday, March 8, 2021 Eric Marcus, Sara Burningham, Nahanni Rous et al. Making Gay History: The Podcast. New York: GLSEN, 2020. Reviewed by Averill Earls (Mercyhurst University)Published on H-Podcast (March, 2021) Commissioned by Robert Cassanello (he/him/his) (University of Central Florida) Printable Version: https://www.h-net.org/reviews/showpdf.php?id=56102 The click of the tape deck door, the grind of play and record pressed at the same time: every episode of Making Gay History opens with a sound that will be familiar to anyone who ever owned a tape deck. These simple but effective touches in the sound design ofMaking Gay History let you know from the start that this is not your average interview radio show. What Eric Marcus and his team give us in this short-form podcast is an invitation into the lives of the people whose labor, organizing, blood, sweat, and tears made gay history in the United States. The show is built from the oral histories that Eric Marcus collected in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Marcus is a journalist with a BA in urban studies and master’s degrees in journalism and real estate development. Though he has several history and queer studies students on his production team at Making Gay History, the majority of those working on the project are in media, with no formally trained historians on staff. Marcus’s twelve published books deal with issues that are close to his heart: LGBT rights, life, and history, and suicide. -

Degeneration Theory in Naturalist Novels of Benito Pérez Galdós

Degeneration Theory in Naturalist Novels of Benito Pérez Galdós A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Michael Wenley Stannard IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Ofelia Ferrán, Advisor April 2011 © Michael Wenley Stannard 2011 i Acknowledgements I should like to record my sincere thanks to Ana Paula Fereira, the Department of Spanish and Portuguese and the University of Minnesota (Twin Cities) for having given me the opportunity to realize a dream of many years. My graduate career in Minnesota has been a life-changing experience, and I would not have missed it for anything. Financial support from the department to study at the Biblioteca Nacional in Madrid, to study Portuguese at the Universidade de Lisboa in Lisbon and to contribute to a conference at Universidad Complutense in Madrid helped significantly in rounding out my graduate student experience, as well as enabling me to collect essential material for this dissertation. I should like to thank my adviser, Ofelia Ferrán, for her help and guidance and to record my additional debt to Toni Dorca and Jaime Hanneken, who listened generously and counseled. To Toni Dorca I owe my introduction to Galdós‘s Naturalist novels which has formed the background of this dissertation. I have seen myself fundamentally as a galdosista at heart ever since. I should like to thank J.B. Shank for allowing me to prevail upon him to direct me in a course of reading that proved invaluable preparation for the study of biological and medical thought in eighteenth and nineteenth century France. -

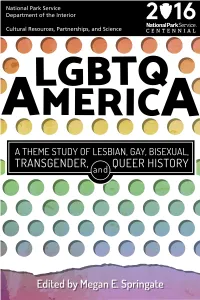

LGBTQ America: a Theme Study of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer History Is a Publication of the National Park Foundation and the National Park Service

Published online 2016 www.nps.gov/subjects/tellingallamericansstories/lgbtqthemestudy.htm LGBTQ America: A Theme Study of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer History is a publication of the National Park Foundation and the National Park Service. We are very grateful for the generous support of the Gill Foundation, which has made this publication possible. The views and conclusions contained in the essays are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the U.S. Government. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute their endorsement by the U.S. Government. © 2016 National Park Foundation Washington, DC All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reprinted or reproduced without permission from the publishers. Links (URLs) to websites referenced in this document were accurate at the time of publication. PLACES Unlike the Themes section of the theme study, this Places section looks at LGBTQ history and heritage at specific locations across the United States. While a broad LGBTQ American history is presented in the Introduction section, these chapters document the regional, and often quite different, histories across the country. In addition to New York City and San Francisco, often considered the epicenters of LGBTQ experience, the queer histories of Chicago, Miami, and Reno are also presented. QUEEREST28 LITTLE CITY IN THE WORLD: LGBTQ RENO John Jeffrey Auer IV Introduction Researchers of LGBTQ history in the United States have focused predominantly on major cities such as San Francisco and New York City. This focus has led researchers to overlook a rich tradition of LGBTQ communities and individuals in small to mid-sized American cities that date from at least the late nineteenth century and throughout the twentieth century. -

Machen, Lovecraft, and Evolutionary Theory

i DEADLY LIGHT: MACHEN, LOVECRAFT, AND EVOLUTIONARY THEORY Jessica George A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy School of English, Communication and Philosophy Cardiff University March 2014 ii Abstract This thesis explores the relationship between evolutionary theory and the weird tale in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Through readings of works by two of the writers most closely associated with the form, Arthur Machen (1863-1947) and H. P. Lovecraft (1890-1937), it argues that the weird tale engages consciously, even obsessively, with evolutionary theory and with its implications for the nature and status of the “human”. The introduction first explores the designation “weird tale”, arguing that it is perhaps less useful as a genre classification than as a moment in the reception of an idea, one in which the possible necessity of recalibrating our concept of the real is raised. In the aftermath of evolutionary theory, such a moment gave rise to anxieties around the nature and future of the “human” that took their life from its distant past. It goes on to discuss some of the studies which have considered these anxieties in relation to the Victorian novel and the late-nineteenth-century Gothic, and to argue that a similar full-length study of the weird work of Machen and Lovecraft is overdue. The first chapter considers the figure of the pre-human survival in Machen’s tales of lost races and pre-Christian religions, arguing that the figure of the fairy as pre-Celtic survival served as a focal point both for the anxieties surrounding humanity’s animal origins and for an unacknowledged attraction to the primitive Other. -

An^ Fluxes Were Rifest

Special Articles AN ACCOUNT OF INDIAN MEDICINE other places on the west coast. After return- ing to England in 1682 he published a BY ' learned and delightful book on India, A new JOHN FRYER, m.d., f.r.s. account of East India and Persia,' which is (1650-1733 A.D.) the basis for this article. By D. V. S. EEDDY Vizagapatam Medical topography : of John Fryer, m.d. (Cantab.), f.r.s., may be Bombay Writing Bombay, Fryer says rightly described as the most observant and that the president has his chaplains, physicians, and domestics. He also learned of all the physicians and surgeons of chyrurgeons refers to the East India Company in the 17th century. the sickly progeny of English women. in He came out to India 1673 and served at 'This may be attributed to their living at large not various settlements in this country and Persia debarring themselves wine and strong drink which, till 1682. During his journey to his immoderately used, influence the blood and spoils the station, milk in these hot as Aristotle he visited Fort St. and Masuli- countries, long ago Surat, George declared. The natives abhor all heady liquours for on patam the Coromandel coast, and Goa and which reason they approve better nurses.' -I Jan., 1940] JOHN FRYER'S ACCOUNT OF INDIAN MEDICINE : REDDY 35 a of the Dust and the of the Air: 'The have only Eyes by fiery Temper Fryer also adds English In the Rains, Fluxes, Apoplexies, and all. Distempers church or burying place but neither ^ ^hospital of the Brain, as well as Stomach.' both which are mightily to be desired.' some diseases Fryer notes the unhealthiness of Bombay. -

No Permanent Waves Bbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbb

No Permanent Waves bbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbb No Permanent Waves Recasting Histories of U.S. Feminism EDITED BY NANCY A. HEWITT bbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbb RUTGERS UNIVERSITY PRESS NEW BRUNSWICK, NEW JERSEY, AND LONDON LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA No permanent waves : recasting histories of U.S. feminism / edited by Nancy A. Hewitt. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978‒0‒8135‒4724‒4 (hbk. : alk. paper)— ISBN 978‒0‒8135‒4725‒1 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Feminism—United States—History. 2. First-wave feminism—United States. 3. Second-wave feminism—United States. 4. Third-wave feminism—United States. I. Hewitt, Nancy A., 1951‒ HQ1410.N57 2010 305.420973—dc22 2009020401 A British Cataloging-in-Publication record for this book is available from the British Library. This collection copyright © 2010 by Rutgers, The State University For copyrights to previously published pieces please see first note of each essay. Pieces first published in this book copyright © 2010 in the names of their authors. All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher. Please contact Rutgers University Press, 100 Joyce Kilmer Avenue, Piscataway, NJ 08854‒8099. The only exception to this prohibition is “fair use” as defined by U.S. copyright law. Visit our Web site: http://rutgerspress.rutgers.edu Manufactured in the United States of America To my feminist friends CONTENTS Acknowledgments xi Introduction 1 NANCY A. HEWITT PART ONE Reframing Narratives/Reclaiming Histories 1 From Seneca Falls to Suffrage? Reimagining a “Master” Narrative in U.S. -

LGBT Identity and Crime

LGBT Identity and Crime LGBT Identity and Crime* JORDAN BLAIR WOODS** Abstract Recent studies report that LGBT adults and youth dispropor- tionately face hardships that are risk factors for criminal offending and victimization. Some of these factors include higher rates of poverty, over- representation in the youth homeless population, and overrepresentation in the foster care system. Despite these risk factors, there is a lack of study and available data on LGBT people who come into contact with the crim- inal justice system as offenders or as victims. Through an original intellectual history of the treatment of LGBT identity and crime, this Article provides insight into how this problem in LGBT criminal justice developed and examines directions to move beyond it. The history shows that until the mid-1970s, the criminalization of homosexuality left little room to think of LGBT people in the criminal justice system as anything other than deviant sexual offenders. The trend to decriminalize sodomy in the mid-1970s opened a narrow space for schol- ars, advocates, and policymakers to use antidiscrimination principles to redefine LGBT people in the criminal justice system as innocent and non- deviant hate crime victims, as opposed to deviant sexual offenders. Although this paradigm shift has contributed to some important gains for LGBT people, this Article argues that it cannot be celebrated as * Originally published in the California Law Review. ** Assistant Professor of Law, University of Arkansas School of Law, Fayetteville. I am thankful for the helpful suggestions from Samuel Bray, Devon Carbado, Maureen Carroll, Steve Clowney, Beth Colgan, Sharon Dolovich, Will Foster, Brian R. -

Conversion Therapy and LGBT Youth Update

AUTHORS: Christy Mallory Conversion Therapy Taylor N.T. Brown and LGBT Youth Kerith J. Conron Update BRIEF / JUNE 2019 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Conversion therapy, also known as sexual orientation or gender identity change efforts, is a practice grounded in the belief that being LGBT is abnormal. It is intended to change the sexual orientation, gender identity, or gender expression of LGBT people.1 Conversion therapy is practiced by some licensed professionals in the context of providing health care and by some clergy or other spiritual advisors in the context of religious practice.2 Efforts to change someone’s sexual orientation or gender identity are associated with poor mental health,3 including suicidality.4 As of June 2019, 18 states, the District of Columbia, and a number of localities have banned health care professionals from using conversion therapy on youth. The Williams Institute estimates that: • 698,000 LGBT adults (ages 18-59)5 in the U.S. have received conversion therapy, including about 350,000 LGBT adults who were subjected to the practice as adolescents.6 • 16,000 LGBT youth (ages 13-17) will receive conversion therapy from a licensed health care professional before they reach the age of 18 in the 32 states that currently do not ban the practice.7 • 10,000 LGBT youth (ages 13-17) live in states that ban conversion therapy and have been protected from receiving conversion therapy from a licensed health care professional before age 18.8 • An estimated 57,000 youth (ages 13-17) across all states will receive conversion therapy from religious or spiritual advisors before they reach the age of 18.9 This report updates conversion therapy estimates published by the Williams Institute in January 2018.10 Conversion Therapy and LGBT Youth | 2 HISTORY Conversion therapy has been practiced in the U.S. -

2020 Annual Report Our Mission

2020 ANNUAL REPORT OUR MISSION Cure Alzheimer’s Fund is a nonprofit organization dedicated to funding research with the highest probability of preventing, slowing or reversing Alzheimer’s disease. Annual Report 2020 MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIRMEN 2 THE MAIN ELEMENTS OF THE PATHOLOGY OF ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE 9 RESEARCH AREAS OF FOCUS 10 PUBLISHED PAPERS 12 CURE ALZHEIMER’S FUND CONSORTIA 20 OUR RESEARCHERS 22 2020 FUNDED RESEARCH 32 2020 EVENTS TO FACILITATE RESEARCH COLLABORATION 68 MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDENT 70 2020 FUNDRAISING 72 2020 FINANCIALS 73 OUR PEOPLE 74 OUR HEROES 75 AWARENESS 78 IN MEMORY AND IN HONOR 80 SUPPORT OUR RESEARCH 81 Message From The Chairmen Dear Friends, 2020 was a truly remarkable year: • Despite the COVID-19 pandemic, we were fully functional with all of our wonderful staff working from their homes. We were able to pay and retain all of our employees, thanks to the generosity of our directors. • And, amazingly, we were able to increase our fundraising by 2%, in this very tough year, to $25.9 million provided by 21,000 donors. • The above enabled us to fund 59 research grants totaling $16.5 million. We have, since inception, financed 525 grants, representing $125 million in cumulative funding through March 2021. • We have one therapy well on its way through clinical trials, and another expected to enter clinical trials in late 2021 or 2022. Our Scientists Approximately 175 scientists affiliated with 75 institutions around the world are working on our projects. They are profiled in the pages that follow. Many labs faced funding challenges during COVID-19, and our consistent support was very beneficial for ensuring that vital staff could be retained and scientific progress was preserved. -

Materials of the President's Personal File Among Nixon Presidential Materials, 1969-74

Materials of the President's Personal File Among Nixon Presidential Materials, 1969-74 The Presidential historical materials of the President's Personal File are in the custody of the National Archives and Records Administration under the provisions of Title I of the Presidential Recordings and Materials Preservation Act of 1974 (P.L. 93-526, 88 Stat. 1695) and implementing regulations. In accordance with the act and regulations, archiv1sts reviewed the file group to identify personal and private materials (including materials outside the date span covered by the act) as well as non-historical items. These materials have been returned to former President Richard M. Nixon or the individual who has primary proprietary interest. Materials covered by the act have been archivally processed and are described in this register. Items which are security classified or otherwise restricted under the act and regulations have been removed and placed in a closed file. A Document Withdrawal Record (GSA Form 7279) with a description of each restricted document has been inserted at the beginning of each folder from which materials have been removed. A Document Control Record marks the original position of the withdrawn item. Employees of the National Archives will review periodically the unclassified portions of closed materials for the purpose of opening those which no longer require restriction. Certain classified documents may be declassified under authority of Executive Order 12356 in response to a Mandatory Review Request (GSA Form 7277) submitted