Skelmanthorpe and District U3A a HISTORY of the TEXTILE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Case Study Scissett Middle School

QUALITY IN CAREERS WEBSITE © CEIAG Case Study: Scissett Middle School, Huddersfield, West Yorkshire The School Scissett Middle School is a 10-13 Middle School situated in the semi-rural Dearne Valley. It has a wide catchment area which includes the villages of Scissett, Denby Dale, Skelmanthorpe, Flockton and Cumberworth. It has around 600 pupils. Children at Scissett Middle School enjoy a wide range of activities which extends their experience in many parts of the curriculum. Health and Safety is emphasised in all School activities and always plays a key role in the organisation of field trips and visits. Vision: To ensure that we are all inspired with a love of learning, a zest for life and the confidence to excel whilst keeping our values at the heart of everything we do. Values: A School that provides outstanding learning opportunities underpinned by a culture of: Respect, Resilience, Excellence, Support, Pride, Enjoyment, Creativity and Trust Career Education, Information, Advice and Guidance (CEIAG) This year the School decided to work towards the Quality in Careers Standard awarded by C&K Careers as a means of pulling together existing practice and to provide a framework for further development. Over the last three years, the pupils have experienced drop down sessions which include Enterprise and Careers. The Enterprise scheme involves the Year 7 pupils working with a charity to raise money from an end of year Summer Fair. The pupils have drop-down days to prepare for this fair and also meet with a variety of local and national charities to learn about what they do. -

A8 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

A8 bus time schedule & line map A8 Laisterdyke - Belle Vue Girls Upper School View In Website Mode The A8 bus line (Laisterdyke - Belle Vue Girls Upper School) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Heaton <-> Laisterdyke: 3:10 PM (2) Laisterdyke <-> Heaton: 7:20 AM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest A8 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next A8 bus arriving. Direction: Heaton <-> Laisterdyke A8 bus Time Schedule 30 stops Heaton <-> Laisterdyke Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 3:10 PM Belle Vue Girls School, Heaton Tuesday 3:10 PM Bingley Rd Thorn Lane, Heaton Wednesday 3:10 PM Bingley Rd Ryelands Grove, Heaton Thursday 3:10 PM Bingley Road, Bradford Friday 3:10 PM Bingley Rd Toller Lane, Heaton Saturday Not Operational Toller Ln Toller Drive, Heaton Toller Ln Heaton Park Drive, Heaton Toller Ln Lynton Drive, Heaton A8 bus Info Direction: Heaton <-> Laisterdyke Toller Lane Masham Place, Heaton Stops: 30 Trip Duration: 47 min Toller Lane Roundabout, Girlington Line Summary: Belle Vue Girls School, Heaton, Bingley Rd Thorn Lane, Heaton, Bingley Rd Ryelands Grove, Heaton, Bingley Rd Toller Lane, Heaton, Toller Lilycroft Rd Westƒeld Road, Girlington Ln Toller Drive, Heaton, Toller Ln Heaton Park Drive, 210-212 Lilycroft Road, Bradford Heaton, Toller Ln Lynton Drive, Heaton, Toller Lane Masham Place, Heaton, Toller Lane Roundabout, Lilycroft Rd Farcliffe Road, Girlington Girlington, Lilycroft Rd Westƒeld Road, Girlington, Lilycroft Rd Farcliffe Road, Girlington, Oak -

At Google Indexer on July 29, 2021 Downloaded From

Downloaded from http://pygs.lyellcollection.org/ by guest on September 25, 2021 214 LIST OF MEMBEKS. ADAMS, THOS., Clifton Grove House, York. ADAMSON, S. A., F.G.S., 48, Caledonian Street, Leeds. AKROYD, ED., F.S.A., &c, Bankfield, Halifax. ALDAM, W., J.P., Frickley Hall, Doncaster. ALEXANDER, WM., J.P., M.D., Halifax. ATKINSON, J. T., F.G.S., The Quay, Selby. BAILEY, GEO., 22, Burton Terrace, York. BAINES, EDWARD, J.P., St. Ann's, Burley, Leeds. BALME, E. B. W-, J.P., Cote Hall, Mirfield. BARBER, F., F.S.A., Castle Hill, Rastrick, near Brighouse. BARBER, W. C, F.R.G.S., The Orphange, Halifax. BARBOUR, J. M., Broad Street, Halifax. BARTHOLOMEW, CHAS., Castle Hill House, Ealing, Middlesex. BARTHOLOMEW, C. "W"., Blakesley Hall, near Toweester. BEAUMONT, HY., Elland. BEDFORD, JAMES, Woodhouse Cliff, Leeds. BEDFORD, J. E., Woodhouse Cliff, Leeds. BEDWELL, F. A., M.A., F.R.M.S., Fort Hall, Bridlington Quay. BERRY, WM., King's Cross Street, Halifax. BINNIE, A. R, F.G.S., M. Inst. C.E., Town Hall, Bradford. BINNS, LEEDHAM, Grore House, Oakenshaw, Bradford. BIRD, C, B.A., F.R.A.S., Grammar School, Bradford. BLAKE, REV. J. F., M.A., F.G.S., 11, Gauden Road, Clapham, London, S.W. BLAKEY, JAS. K., F.G.S., 23, Fountain Street, Leeds. BOOTH, EDWIN, Barnsley. BOOTHROYD, W., Brighouse. BOWMAN, F. H., F.R.A.S., F.C.S., F.G.S., Halifax. BRADLEY, GEORGE, Aketon Hall, Featherstone. BRIGG, JOHN, J.P., F.G.S., Broomfield, Keighley. BROADHEAD, JOHN, St. John's Colliery, Normanton. BROOKE, ED., Jun., F.G.S., Fieldhouse Clay Works, Huddersfield. -

4 June 2017: PENTECOST

The Parish of Holy Trinity Bingley with St Wilfrid Gilstead Coming Up 12 Jun TASS re-opens 13 Jun St Anthony of Padua www.bingley.church 10.00am EUCHARIST (HT) www.facebook.com holytrinityandstwilfridsbingley 10.30am MU Summer Trip (dep. HT) https://twitter.com/andrewclarkebd 7.00pm Holy Hour (HT) 14 Jun 8.30pm Vespers for the Feast of Corpus Christi 4 June 2017: PENTECOST (St Chad’s, Toller Lane) A warm welcome to all who have come church today, 15 Jun CORPUS CHRISTI especially those who are visiting, Genesis 14.18-20; 1 Corinthians 11.23-26; John 6.51-58 or attending for the first time, or the first time in a while. 9.00am KS1 Service (HT) If you do not have to rush away, 9.30am Reception Service (HT) please stay for fellowship after the service. 10.00am KS2 Service (HT) The Holy Spirit calls us together, giving us the joy 10.45am Nursery Praise (HT) 2.45pm Nursery Praise (HT) and privilege of calling God Father, through the 7.00pm PARISH EUCHARIST (SW) work of the Son. Let us worship as God’s holy peo- President & Preacher: The Vicar. ple. Acts 2.1-21: The Holy Spirit equips the disciples to witness to Jesus. 16 Jun St Richard 1 Corinthians 12.3-13: The Spirit gives the Church all the gifts it needs 8.15am EUCHARIST (HT) to do its work for Jesus. 4.00pm HOLY COMMUNION (AVCt) John 20.19-23: The risen Jesus breathes his Spirit on the disciples. 9.15am SUNG EUCHARIST (HT) 18 Jun 1st SUNDAY AFTER TRINITY President & Preacher: The Vicar. -

Beginning to Knit

Beginning To Knit This Lesson is reprinted by permission Pull down on both ends of the yarn to tighten the knot. of TNNA and contains portions of the Diagram 21. “How to Knit” book published by The Diagram 21 National NeedleArts Association (www. TNNA.org). Find full details for the new knitter in the complete “How to Knit” book available at your local yarn shop. Casting On - Double Cast On Method Measure off a length of yarn allowing one inch for each stitch you will cast on. Your pattern instructions will To cast on the second stitch, and all subsequent stitches, indicate this number. Make a slip-knot, it will be your hold the needle with the slip-knot in your right hand. first stitch. To make a slip-knot, make a pretzel shape Drape the short end of yarn over the thumb and the with the yarn and slip the needle into the pretzel as yarn from the ball over the index finger. Gently pull the shown. Diagrams 19 & 20. two ends of yarn apart to tighten the loop. Take care not to tighten it too much. The stitch should glide easily over the needle. Both strands of yarn should rest Diagram 19 in the palm of the left hand, with the last two fingers holding them down. Diagram 22. Diagram 22 Diagram 20 How To Knit Pull the needle downward, then insert the point of the Drop the thumb loop, then pull on the short end of needle up through the loop that is on your thumb. yarn with your thumb. -

Applications and Decisions for the North East of England

OFFICE OF THE TRAFFIC COMMISSIONER (NORTH EAST OF ENGLAND) APPLICATIONS AND DECISIONS PUBLICATION NUMBER: 6329 PUBLICATION DATE: 06/02/2019 OBJECTION DEADLINE DATE: 27/02/2019 Correspondence should be addressed to: Office of the Traffic Commissioner (North East of England) Hillcrest House 386 Harehills Lane Leeds LS9 6NF Telephone: 0300 123 9000 Fax: 0113 248 8521 Website: www.gov.uk/traffic-commissioners The public counter at the above office is open from 9.30am to 4pm Monday to Friday The next edition of Applications and Decisions will be published on: 13/02/2019 Publication Price 60 pence (post free) This publication can be viewed by visiting our website at the above address. It is also available, free of charge, via e-mail. To use this service please send an e-mail with your details to: [email protected] APPLICATIONS AND DECISIONS General Notes Layout and presentation – Entries in each section (other than in section 5) are listed in alphabetical order. Each entry is prefaced by a reference number, which should be quoted in all correspondence or enquiries. Further notes precede each section, where appropriate. Accuracy of publication – Details published of applications reflect information provided by applicants. The Traffic Commissioner cannot be held responsible for applications that contain incorrect information. Our website includes details of all applications listed in this booklet. The website address is: www.gov.uk/traffic-commissioners Copies of Applications and Decisions can be inspected -

SITE PLAN and AMENITIES Barnsley Road, Flockton WF4 4AA Barnsley Road, Flockton WF4 4AA

SITE PLAN AND AMENITIES Barnsley Road, Flockton WF4 4AA Barnsley Road, Flockton WF4 4AA Development layouts and landscaping are not intended to form part of any contract or warranty unless specifically incorporated in writing into the contract. Images and development layouts are for illustrative purposes and should be used for general guidance only. Development layouts including parking arrangements, social/affordable housing housing and public open spaces may change to reflect changes in planning permission and are not intended to form part of any contract or warranty unless specifically incorporated in writing. Please speak to your solicitor to whom full details of any planning consents including layout plans will be available. Chapel Lea is a marketingname only and may notbe thedesignated postal address, which may be determined by The Post Office. Calls to our 0844 numbers cost 7 pence perminute plus your phone company’s access charge. SP348054 LOCAL AMENITIES CHAPEL LEA DOCTORS NURSERIES Tesco Express Scissett Baths & Fitness Centre Flockton Surgery The Co-operative Childcare Dewsbury Huddersfield Road, Mirfield WF14 8AN 116 Wakefield Road, Scissett HD8 9HU Moor Nursery 101 Barnsley Road, Flockton WF4 4DH 100 Heckmondwike Road, Dewsbury Sainsbury’s Alhambra Shopping Centre WF13 3NT DENTISTS Railway Street, Dewsbury WF12 8EB Cheapside, Barnsley S70 1SB Hamond House Day Nursery Horbury Dental Care 25 Battye Street, Heckmondwike WF16 POST OFFICE Fox Valley 9ES Vincent House, Queen Street, Horbury Emley Post Office Fox Valley Way, Stocksbridge -

Honley High School – About Us

Honley High School – About Us At Honley High School we have a long and proud tradition of academic excellence, a strength on which we are continually trying to build. Although the school is quite large (we have over 1280 students) we like to feel that we get to know all our students, as individuals, and are able to support them through what we all acknowledge, is a crucial time in their lives. Central to everything we are working to achieve is the school vision. We are striving to create an exceptional school where all members of the school community: - Are proud of the school, respectful of each other, socially responsible, and believe in and promote our values - Work within an atmosphere of mutual support, respect and collaboration - Are committed to individual and collective success and place no ceiling on aspiration; - Celebrate effort as well as achievement, take risks and learn from mistakes, recognising the intrinsic value of learning - Place the needs of the child at the centre of learning, nurture their creativity in overcoming the challenges of today and develop their resilience to address the uncertainties of tomorrow The exceptional school that we will create will be founded upon the following beliefs: - We believe in fairness, equity and inclusion: we value every child for who they are and show compassion and understanding in our dealings with one another - We strive for excellence in everything we do: we have high aspirations for everyone and believe that children and adults thrive in a climate of praise, celebration and recognition. We always measure ourselves against the highest standards. -

A Special and Unusual Loom Frame from the First Half of the Nine

FINDING THE THREAD RESTORATION OF A PROFESSIONAL WEAVER'S LOOM Rabbit Goody A special and unusual loom frame from the first half of the nine teenth century now in the collection of the Ontario Agricultural Mu seum, Milton, Ontario,1 has provided an opportunity to examine some of the specialized equipment used by weavers in the nineteenth century to weave cloth with speed, intricate geometric patterns, and/or accommodate longer lengths of cloth. Surviving examples of cloth have made it apparent that trained weavers, weaving fancy cloth during the nineteenth century were using more complex equipment than that commonly associated with home textile produc tion. However, until now surviving examples of the equipment have been scarce. The museum's loom is one of a small number that can be linked to the production of the more complex cloths of this pe riod. At least, it has specialized equipment which professional weavers might choose to place on their looms. It is the most com plete example currently known. In their book, "Keep Me Warm One Night", Dorothy and Harold Burnham have identified this loom as being a professional weaver's loom because of its specialized features.2 It is being restored for the purpose of reproducing some of the more intricate cloth woven by professional weavers in the Niagara Peninsula. The survival of this loom frame, with its special features, has made it possible to set certain criteria for identifying other looms used by professionals and to corroborate the descrip tions of equipment and methods found in publications and manuscripts from the last half of the eighteenth century and early nineteenth century used to weave fancy cloth rapidly by profes sionals. -

3Needle Bind-Of

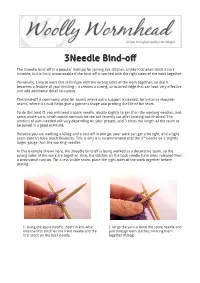

3Needle Bind-of The 3needle bind-off is a popular method for joining live stitches. Unlike Kitchener stitch it isn't invisible, but is fairly unnoticeable if the bind-off is worked with the right sides of the work together. Personally, I like to work this technique with the wrong sides of the work together, so that it becomes a feature of your knitting – it creates a strong, structured ridge that can look very effective and add additional detail to a piece. This bind-off is commonly used for seams where extra support is needed, for instance shoulder seams, where it's bulk helps give a garment shape and prolong the life of the seam. To do this bind-ff, you will need a spare needle, ideally slightly larger than the working needles, and some waste yarn, which would normally be the tail recently cut after knitting has finished. The amount of yarn needed will vary depending on your project, and 3 times the length of the seam to be joined is a good estimate. Because you are working a k2tog and a cast-off in one go, your work can get a bit tight, and a tight seam doesn't have much flexibility. This is why it is recommended that the 3rd needle be a slightly larger gauge than the working needles. In this example shown here, the 3needle bind-off is being worked as a decorative seam, so the wrong sides of the work are together. Also, the stitches on the back needle have been released from a provisional cast-on. -

Young People's Engagement

Young People’s Engagement “Our lives during a pandemic” Outreach Key Messages July-August 2020 Covid-19 ‘National Lockdown’ Measures were put in place in March 2020. Contents Children, young people and their families Where did we visit and what 1 were asked to ‘Stay home, save lives and protect our NHS’. did we do? Therefore, from April to July 2020 Our Voice engaged with young people online. What did young people share? -Covid 19 As soon as restrictions were relaxed and 2 -Our Learning and Futures we were able to find young people in 3 parks and open spaces, we did. -The importance of recreation 4 and play We asked about their experiences of navigating a global pandemic, the changes that have resulted and what’s What Next? 5 important to them. Here is a summary of what they told us… Where did we visit and what did we do? The main purpose of the outreach sessions was to promote the Our Voice We have also met virtually with the LGBTQ+ Youth Programme and encourage young people from across Kirklees to join in! We Group at the Brunswick Centre, the Children in know there will be exciting experiences and opportunities available, for Care Council and Care Leavers Council. them to make a difference in the coming months. We have spoken to 238 children and young people* this Summer, their ages Spen Valley In North Kirklees, we visited: Cleckheaton have varied from 8-23. Alongside promoting our current projects, we have Batley Birstall also asked young people how they have managed ‘lockdown’ and what they Heckmondwike feel about the coming months… -

Coeliac UK – Calderdale & Huddersfield Group

Coeliac UK – Calderdale & Huddersfield Group. We strongly recommend that you phone beforehand to confirm that your needs will be met. A change of ownership or chef may mean loss of awareness. NAME ADDRESS ADDRESS ADDRESS TEL. NO. OTHER INFORMATION 1885 The Restaurant Stainland Road Stainland HX4 9PJ 01422 373030 2 Oxford Place 2 Oxford Place Leeds LS1 3AX 0113 234 1294 www.2oxfordplace.com Aagrah 250 Wakefield Road Denby Dale HD8 8SU 01484 866266 GF marked on menu Angel Inn Hetton Skipton BD23 6LT 01756 730263 [email protected] Aux Delices 15 Burnley Road Mytholmroyd HX7 5LH 01422 885564 [email protected] Beatson House 2 Darton Road Cawthorne,Barnsley S75 4HR 01226 791245 [email protected] Beatties Deli & Coffee Shop 6 Towngate Holmfirth HD9 1HA 01484 689000 www.area5.co.uk/beatties Beeches Brasserie School Lane Standish, Wigan WN6 0TD 01257 426432 beecheshotel.co.uk Bengal Spice Dunford Road Holmfirth HD9 2DP 01484 685239 Beresford’s Restaurant Beresford Road Windermere LA23 2JG 01539 488488 beresfordsrestautantandpub.co.uk Boggart Brig Tea Room Ogden Lane Halifax HX2 8XZ 01422 647805 Open Wed to Sat/March to November Booth Wood Inn Oldham Road Rishworth HX6 4QU 01422 825600 Bradleys Restaurant 84 Fitzwilliam Street Huddersfield HD1 5BB 01484 516773 Brassiere at The Bull 5 Bull Green Halifax HX1 5AB 01422 330833 brasserieatthebull.co.uk Brooks 6 Bradford Road Brighouse HD6 1RW 01484 715284 Caffe Barca & Tearooms, Top Red Brick Mill, Floor 213 Bradford Road Batley WF17 6JF 01924 437444 [email protected] Café Concerto