'Ma Is in the Park': Memory, Identity, and the Bethune

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The National Gallery of Art (NGA) Is Hosting a Special Tribute and Black

SIXTH STREET AT CONSTITUTION AVENUE NW WASHINGTON DC 20565 • 737-4215 extension 224 MEDIA ADVISORY WHAT: The National Gallery of Art (NGA) is hosting a Special Tribute and Black-tie Dinner and Reception in honor of the Founding and Retiring Members of the Congressional Black Caucus (CBC). This event is a part of the Congressional Black Caucus Foundation's (CBCF) 20th Annual Legislative Weekend. WHEN: Wednesday, September 26, 1990 Working Press Arrival Begins at 6:30 p.m. Reception begins at 7:00 p.m., followed by dinner and a program with speakers and a videotape tribute to retiring CBC members Augustus F. Hawkins (CA) , Walter E. Fauntroy (DC), and George Crockett (MI) . WHERE: National Gallery of Art, East Building 4th Street and Constitution Ave., N.W. SPEAKERS: Welcome by J. Carter Brown, director, NGA; Occasion and Acknowledgements by CBC member Kweisi Mfume (MD); Invocation by CBC member The Rev. Edolphus Towns (NY); Greetings by CBC member Alan Wheat (MO) and founding CBC member Ronald Dellums (CA); Presentation of Awards by founding CBC members John Conyers, Jr. (MI) and William L. Clay (MO); Music by Noel Pointer, violinist, and Dr. Carol Yampolsky, pianist. GUESTS: Some 500 invited guests include: NGA Trustee John R. Stevenson; (See retiring and founding CBC members and speakers above.); Founding CBC members Augustus F. Hawkins (CA), Charles B. Rangel (NY), and Louis Stokes (OH); Retired CBC founding members Shirley Chisholm (NY), Charles C. Diggs (MI), and Parren Mitchell (MD) ; and many CBC members and other Congressional leaders. Others include: Ronald Brown, Democratic National Committee; Sharon Pratt Dixon, DC mayoral candidate; Benjamin L Hooks, NAACP; Dr. -

Black Women, Educational Philosophies, and Community Service, 1865-1965/ Stephanie Y

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-2003 Living legacies : Black women, educational philosophies, and community service, 1865-1965/ Stephanie Y. Evans University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Evans, Stephanie Y., "Living legacies : Black women, educational philosophies, and community service, 1865-1965/" (2003). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 915. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/915 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. M UMASS. DATE DUE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS AMHERST LIVING LEGACIES: BLACK WOMEN, EDUCATIONAL PHILOSOPHIES, AND COMMUNITY SERVICE, 1865-1965 A Dissertation Presented by STEPHANIE YVETTE EVANS Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2003 Afro-American Studies © Copyright by Stephanie Yvette Evans 2003 All Rights Reserved BLACK WOMEN, EDUCATIONAL PHILOSOHIES, AND COMMUNITY SERVICE, 1865-1964 A Dissertation Presented by STEPHANIE YVETTE EVANS Approved as to style and content by: Jo Bracey Jr., Chair William Strickland, -

The "Stars for Freedom" Rally

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Selma-to-Montgomery National Historic Trail The "Stars for Freedom" Rally March 24,1965 The "March to Montgomery" held the promise of fulfilling the hopes of many Americans who desired to witness the reality of freedom and liberty for all citizens. It was a movement which drew many luminaries of American society, including internationally-known performers and artists. In a drenching rain, on the fourth day, March 24th, carloads and busloads of participants joined the march as U.S. Highway 80 widened to four lanes, thus allowing a greater volume of participants than the court- imposed 300-person limitation when the roadway was narrower. There were many well-known celebrities among the more than 25,000 persons camped on the 36-acre grounds of the City of St. Jude, a Catholic social services complex which included a school, hospital, and other service facilities, located within the Washington Park neighborhood. This fourth campsite, situated on a rain-soaked playing field, held a flatbed trailer that served as a stage and a host of famous participants that provided the scene for an inspirational performance enjoyed by thousands on the dampened grounds. The event was organized and coordinated by the internationally acclaimed activist and screen star Harry Belafonte, on the evening of March 24, 1965. The night "the Stars" came out in Alabama Mr. Belafonte had been an acquaintance of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. since 1956. He later raised thousands of dollars in funding support for the Freedom Riders and to bailout many protesters incarcerated during the era, including Dr. -

Waveland, Mississippi, November 1964: Death of Sncc, Birth of Radicalism

WAVELAND, MISSISSIPPI, NOVEMBER 1964: DEATH OF SNCC, BIRTH OF RADICALISM University of Wisconsin – Eau Claire: History Department History 489: Research Seminar Professor Robert Gough Professor Selika Ducksworth – Lawton, Cooperating Professor Matthew Pronley University of Wisconsin – Eau Claire May 2008 Abstract: The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC, pronounced Snick) was a nonviolent direct action organization that participated in the civil rights movement in the 1960s. After the Freedom Summer, where hundreds of northern volunteers came to participate in voter registration drives among rural blacks, SNCC underwent internal upheaval. The upheaval was centered on the future direction of SNCC. Several staff meetings occurred in the fall of 1964, none more important than the staff retreat in Waveland, Mississippi, in November. Thirty-seven position papers were written before the retreat in order to reflect upon the question of future direction of the organization; however, along with answers about the future direction, these papers also outlined and foreshadowed future trends in radical thought. Most specifically, these trends include race relations within SNCC, which resulted in the emergence of black self-consciousness and an exodus of hundreds of white activists from SNCC. ii Table of Contents: Abstract ii Historiography 1 Introduction to Civil Rights and SNCC 5 Waveland Retreat 16 Position Papers – Racial Tensions 18 Time after Waveland – SNCC’s New Identity 26 Conclusion 29 Bibliography 32 iii Historiography Research can both answer questions and create them. Initially I discovered SNCC though Taylor Branch’s epic volumes on the Civil Right Movements in the 1960s. Further reading revealed the role of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC, pronounced Snick) in the Civil Right Movement and opened the doors into an effective and controversial organization. -

Women in the Modern Civil Rights Movement

Women in the Modern Civil Rights Movement Introduction Research Questions Who comes to mind when considering the Modern Civil Rights Movement (MCRM) during 1954 - 1965? Is it one of the big three personalities: Martin Luther to Consider King Jr., Malcolm X, or Rosa Parks? Or perhaps it is John Lewis, Stokely Who were some of the women Carmichael, James Baldwin, Thurgood Marshall, Ralph Abernathy, or Medgar leaders of the Modern Civil Evers. What about the names of Septima Poinsette Clark, Ella Baker, Diane Rights Movement in your local town, city or state? Nash, Daisy Bates, Fannie Lou Hamer, Ruby Bridges, or Claudette Colvin? What makes the two groups different? Why might the first group be more familiar than What were the expected gender the latter? A brief look at one of the most visible events during the MCRM, the roles in 1950s - 1960s America? March on Washington, can help shed light on this question. Did these roles vary in different racial and ethnic communities? How would these gender roles On August 28, 1963, over 250,000 men, women, and children of various classes, effect the MCRM? ethnicities, backgrounds, and religions beliefs journeyed to Washington D.C. to march for civil rights. The goals of the March included a push for a Who were the "Big Six" of the comprehensive civil rights bill, ending segregation in public schools, protecting MCRM? What were their voting rights, and protecting employment discrimination. The March produced one individual views toward women of the most iconic speeches of the MCRM, Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a in the movement? Dream" speech, and helped paved the way for the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and How were the ideas of gender the Voting Rights Act of 1965. -

A Mediagraphy Relating to the Black Man

racumEN7 RESUME ED 033 943 IE 001 593 AUTHOR Parker, James E., CcmF. TITLE A Eediagraphy Relating to the Flack Man. INSTITUTION North Carclina Coll., Durham. Pub Date May 69 Note 82F. EDRS Price EDRS Price MF-$0.50 BC Not Available from EDRS. Descriptors African Culture, African Histcry, *Instructional Materials, *Mass Media, *Negro Culture, *Negro Histcry, Negro leadership, *Negro Literature, Negro Ycuth, Racial Eiscriminaticn, Slavery Abstract Media dealing with the Black man--his history, art, problems, and aspirations--are listed under 10 headings:(1) disc reccrdings,(2) filmstrips and multimedia kits, (3) microfilms, (4) motion pictures, (5) pictures, Fcsters and charts,(6) reprints,(7) slides, (8) tape reccrdings, (9) telecourses (kinesccFes and videotapes), and (10) transparencies. Rentalcr purchase costs of the materials are usually included, andsources and addresses where materials may be obtainedare appended. [Not available in hard cecy due tc marginal legibility of original dccument.] (JM) MEDIA Relatingto THE BLACKMAN by James E. Parker U.). IMPARIMUll OF !ULM,tOUGAI1011 &WINE OfFKE OF EDUCATION PeN THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRODUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON 02 ORGANIZATION ORIGINATING IT. POINTS OF VIEW OR OPINIONS Ci STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRESENT OFFICIAL OFFICE OF EDUCATION re% POSITION OR POLICY. O1 14.1 A MEDIAGRAPHY RELATING TO THE BLACK MAN Compiled by James E. Parker, Director Audiovisual-Television Center North Carolina College at Durham May, 1969 North Carolina College at Durham Durham, North Carolina 27707 .4 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ii FOREWORD iii DISC RECORDINGS 1-6 FILMSTRIPS AND MULTIMEDIA KITS 7- 18 MICROFILMS 19- 25 NOTION PICTURES 26- 48 PICTURES, POSTERS, CHARTS. -

Transafrica Board of Directors

TRANSAFRICA BOARD OF DIRECTORS The Honorable Richard Gordon Hatcher Chairman Harry Belafonte William Lucy Reverend Charles Cobb Dr. Leslie Mclemore Courtland Cox Marc Stepp The Honorable Ronald Dellums The Honorable Percy Sutton Dr. Dorothy Height Dr. James Turner Dr. Sylvia Hill Reverend Wyatt Tee Walker Dr. Willard Johnson The Honorable Maxine Waters Robert White Randall Robinson Executive Director SPONSORS African and Caribbean Diplomatic Corps His Excellency Jose Luis Fernandes Lopes His Excellency Jean Robert Odgaza His Excellency Willem A. Udenhout Cape Verde Gabon Sun·nanze His Excellency Abdellah Ould Daddah His Excellency Charles Gomis His Excellency Dr. Paul John Firmino Lusaka Mauritania Cote d 'luoire Zambia His Excellency Keith Johnson Her Excellency Eugenia A. Wordsworth-Stevenson His Excellency Stanislaus Chigwedere Jamaica li/x>ria Zimbabwe His Excellency P'dul Pondi His Excellency Sir William Douglas His Excellency Jean Pierre Sohahong-Kombet Cameroon Barbados Central African Republic His Excellency Chitmansing J esseramsing His Excellency Alhaji Hamzat Ahmadu His Excellency Pierrot]. Rajaonarivelo Mauritius Nigeria Madagascar His Excellency Dr. Cedric Hilburn Grant His Excellency Ousman Ahmadou Sallah His Excellency Abdalla A. Abdalla Guyana The Gambia Sudan His Excellency Edmund Hawkins Lake His Excellency Aloys Uwimana His Excellency Mohamed Toure Antigua and BarlJuda Rwanda Mali His Excellency Ellom-Kodjo Schuppius His Excellency Roble Olhaye His Excellency Moussa Sangare Togo Djibouti Guinea His Excellency Mahamat -

Biographical Sketch of Fannie Lou Hamer

ERICA AM F E IN C D OI YOUR V Fannie Lou Hamer: A Biographical Sketch By Maegan Parker Brooks, PhD “I question America. Is this America, the land of the free and the home of the brave, where we have to sleep with our telephones off the hook because our lives be threatened daily, because we want to live as decent human beings, in America?” With this critical question, delivered at the 1964 Democratic National Convention, Fannie Lou Hamer became revered across the nation. Malcolm X referred to her as the “country’s number one freedom fighting woman” and rumor has it Martin Luther King, Jr—though he loved her dearly— feared being upstaged by Hamer’s soul-stirring speeches. Over her lifetime (1917-1977), Fannie Lou Hamer traveled from the Delta of Mississippi to the Atlantic City Boardwalk, from Washington, D.C. to Washington State, from Madison, Wisconsin to Conakry, Guinea—always proclaiming the social gospel that all human beings are created equal and that all people are entitled to basic rights of food, FIGURE 1: Fannie Lou Hamer addresses the shelter, dignity, and a voice in the government to 1964 Democratic National Convention. which they belong. Fannie Lou Hamer held strong convictions, but she was no idealist. Born the twentieth child of James Lee and Lou Ella Townsend, Fannie Lou and her large family struggled to survive as sharecroppers on plantations controlled by Whites. As an outgrowth of slavery, the sharecropping system was largely designed to keep Black people indebted to White landowners. This economic control held social and political implications as well. -

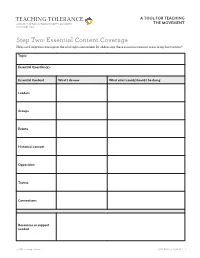

Step Two: Essential Content Coverage How Can I Improve Coverage of the Civil Rights Movement by Addressing These Essential Content Areas in My Instruction?

TEACHING TOLERANCE A TOOL FOR TEACHING A PROJECT OF THE SOUTHERN POVERTY LAW CENTER THE MOVEMENT TOLERANCE.ORG Step Two: Essential Content Coverage How can I improve coverage of the civil rights movement by addressing these essential content areas in my instruction? Topic: Essential Question(s): Essential Content What I do now What else I could/should I be doing Leaders Groups Events Historical context Opposition Tactics Connections Resources or support needed © 2014 Teaching Tolerance CIVIL RIGHTS DONE RIGHT TEACHING TOLERANCE A TOOL FOR TEACHING A PROJECT OF THE SOUTHERN POVERTY LAW CENTER THE MOVEMENT TOLERANCE.ORG Step Two: Essential Content Coverage (SAMPLE) How can I improve coverage of the civil rights movement by addressing these essential content areas in my instruction? Topic: 1963 March on Washington Essential Question(s): How do the events and speeches of the 1963 March on Washington illustrate the characteristics of the civil rights movement as a whole? Essential Content What I do now What else I could/should be doing Leaders Martin Luther King Jr., Bayard Rustin, James Farmer, John Lewis, Roy A. Philip Randolph Wilkins, Whitney Young, Dorothy Height Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), Student Nonviolent Groups Coordinating Committee (SNCC), Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP), National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), National Urban League (NUL), Negro American Labor Council (NALC) The 1963 March on Washington was one of the most visible and influential Some 250,000 people were present for the March Events events of the civil rights movement. Martin Luther on Washington. They marched from the Washington King Jr. -

ELLA BAKER, “ADDRESS at the HATTIESBURG FREEDOM DAY RALLY” (21 January 1964)

Voices of Democracy 11 (2016): 25-43 Orth 25 ELLA BAKER, “ADDRESS AT THE HATTIESBURG FREEDOM DAY RALLY” (21 January 1964) Nikki Orth The Pennsylvania State University Abstract: Ella Baker’s 1964 address in Hattiesburg reflected her approach to activism. In this speech, Baker emphasized that acquiring rights was not enough. Instead, she asserted that a comprehensive and lived experience of freedom was the ultimate goal. This essay examines how Baker broadened the very idea of “freedom” and how this expansive notion of freedom, alongside a more democratic approach to organizing, were necessary conditions for lasting social change that encompassed all humankind.1 Key Words: Ella Baker, civil rights movement, Mississippi, freedom, identity, rhetoric The storm clouds above Hattiesburg on January 21, 1964 presaged the social turbulence that was to follow the next day. During a mass meeting held on the eve of Freedom Day, an event staged to encourage African-Americans to vote, Ella Baker gave a speech reminding those in attendance of what was at stake on the following day: freedom itself. Although registering local African Americans was the goal of the event, Baker emphasized that voting rights were just part of the larger struggle against racial discrimination. Concentrating on voting rights or integration was not enough; instead, Baker sought a more sweeping social and political transformation. She was dedicated to fostering an activist identity among her listeners and aimed to inspire others to embrace the cause of freedom as an essential element of their identity and character. Baker’s approach to promoting civil rights activism represents a unique and instructive perspective on the rhetoric of that movement. -

Print ED381426.TIF (18 Pages)

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 381 426 SO 024 676 AUTHOR Barnett, Elizabeth F. TITLE Mary McLeod Bethune: Feminist, Educator, and Social Activist. Draft. PUB DATE 94 NOTE 18p.; Paper presented at the Annual Conference of the American Educational Research Association (New Orleans, LA, April 4-9, 1994). PUB TYPE Speeches/Conference Papers (150) Reports Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE MFO1 /PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Blacks; *Black Studies; Civil Rights; Cultural Pluralism; *Culture; *Diversity (Institutional); Females; *Feminism; Higher Education; *Multicultural Education; Secondary Education; *Women' Studies IDENTIFIERS *Bethune (Mary McLeod) ABSTRACT Multicultural education in the 1990s goes beyond the histories of particular ethnic and cultural groups to examine the context of oppression itself. The historical foundations of this modern conception of multicultural education are exemplified in the lives of African American women, whose stories are largely untold. Aspects of current theory and practice in curriculum transformation and multicultural education have roots in the activities of African American women. This paper discusses the life and contributions of Mary McLeod Bethune as an example of the interconnections among feminism, education, and social activism in early 20th century American life. (Author/EH) *********************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made frt. the original doci'ment. ***************************A.****************************************** MARY MCLEOD BETHUNE: FEMINIST, EDUCATOR, AND SOCIAL ACTIVIST OS. 01411111111111T OP IMILICATION Pico of EdwoOomd Ill000s sod Idoomoome EDUCATIOOKL. RESOURCES ortaevAATION CENTEO WW1 Itfto docamm was MOO 4144116414 C111fteico O OM sown et ogimmio 0940411 4 OWV, Chanin him WWI IWO le MUM* 41014T Paris of lomat olomomosiedsito dew do rot 110011441104, .611.1181184 MON OEM 001140 01040/ Elizabeth F. -

Social Studies TOPIC U.S

2018-2019 Reading List Social Studies TOPIC U.S. Civil Rights Movements: Fulfilling a Nation’s Promise PRIMARY READING SELECTION The Race Beat: The Press, the Civil Rights Struggle, and the Awakening of a Nation, by Gene Roberts and Hank Klibanoff Vintage; (2007) ISBN: 978-0679735656! Available from Texas Educational Paperbacks, Inc ! 800-443-2078 www.tepbooks.com List price: $17.00, TEP UIL price: $11.05 plus shipping Also available from most online book sellers SUPPLEMENTAL READING MATERIAL Supreme Court Cases • Dred Scott v. Sanford (1856) • Roe v. Wade (1973) • Civil Rights Cases (1883) • Lau v. Nichols (1974) • Yick Wo v. Hopkins (1886) • Plyler v. Doe (1982) • Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) • Meritor Savings Bank v. Vinson (1986) • Missouri ex el Gaines v. Canada (1938) • Bowers v. Hardwick (1986) • Shelley v. Kraemer (1948) • UAW v. Johnson Controls (1991) • Sweatt v. Painter (1950) • Franklin v. Gwinnett County Public Schools • Briggs v. Elliot (1952) (1992) • Hernandez v. Texas (1954) • US v. Virginia (1996) • Brown v. Board of Education (1954) • Romer v. Evans (1996) • Brown v. Board of Education II (1955) • Faragher v. City of Boca Raton (1998) • Browder v Gayle (1956) • Lawrence v. Texas (2003) • Heart of Atlanta Motel Inc. v. U.S. (1964) • Shelby County v. Holder (2013) • Loving v. Virginia (1967) • United States v. Windsor (2013) • Jones v. Mayer Co. (1968) • Burwell v. Hobby Lobby Stores, Inc. (2014) • Griggs v. Duke Power Co. (1971) • Obergefell v. Hodges (2015) Legislation th th th th • Title IX of the Federal Education • 5 , 14 , 15 , 24 Amendments • Civil Rights Act of 1875 Amendments (1972) • Civil Rights Act of 1957 • Equal Rights Amendment (1972) • Civil Rights Act of 1964 • Civil Rights Restoration Act of 1987 • Voting Rights Act (1965) • Americans with Disabilities Act of • Fair Housing Act (1968) 1990 Speeches & Movement Documents • The Seneca Falls Declaration of Sentiments • I’ve Been to the Mountaintop, Martin Luther (1848) King, Jr.