Fannie Lou Hamer, Dorothy Height, and Viola Liuzzo: Not

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Emmett Till-‐ the Murder That Sparked the Civil Rights Movement Emmitt Till

Emmett Till- The Murder that sparked the Civil Rights Movement Emmitt Till Travel Exhibit on display in classroom. Day 1- Students will watch The PBS documentary on the Murder of Emmett Till And students will keep a journal of key events, locations, and people related to this historical event. Day 2-Guest Speaker Lent Rice- Current Director Bureau of Professional Standards of the Desoto Sheriff’s Department. Lived in Sumner Mississippi when the Emmett Till murder trial occurred and was on the FBI investigation team to reopen the Emmett Till Murder case in 2006. Students will watch videos of Wheeler Parker and Simeon Wright ( from the Delta Center Archives ) share what happened in the store , the night Emmett Till was kidnapped, and the murder trial. Students will have copies of The Court Reporter activities from the Delta Center and complete the student activities on the Emmett Till traveling exhibit. Day 3- Primary Source – students will be provided with a copy of the lyrics to the Bob Dylan song, the murder of Emmett Till, and follow along as they listen to Bob Dylan perform the song. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RVKTx9YlKls DAY 3 – Students in small groups will be provided with articles from the Mississippi History Archives on Acts of Civil disobedience in Mississippi. and must write and perform their own Protest Song based on one of the historical events. (This lesson plan is available on the website the Mississippi Department of Archives and History) Day 4- Student groups will perform protest songs in class. Awards will be granted to best performance and best song. -

The National Gallery of Art (NGA) Is Hosting a Special Tribute and Black

SIXTH STREET AT CONSTITUTION AVENUE NW WASHINGTON DC 20565 • 737-4215 extension 224 MEDIA ADVISORY WHAT: The National Gallery of Art (NGA) is hosting a Special Tribute and Black-tie Dinner and Reception in honor of the Founding and Retiring Members of the Congressional Black Caucus (CBC). This event is a part of the Congressional Black Caucus Foundation's (CBCF) 20th Annual Legislative Weekend. WHEN: Wednesday, September 26, 1990 Working Press Arrival Begins at 6:30 p.m. Reception begins at 7:00 p.m., followed by dinner and a program with speakers and a videotape tribute to retiring CBC members Augustus F. Hawkins (CA) , Walter E. Fauntroy (DC), and George Crockett (MI) . WHERE: National Gallery of Art, East Building 4th Street and Constitution Ave., N.W. SPEAKERS: Welcome by J. Carter Brown, director, NGA; Occasion and Acknowledgements by CBC member Kweisi Mfume (MD); Invocation by CBC member The Rev. Edolphus Towns (NY); Greetings by CBC member Alan Wheat (MO) and founding CBC member Ronald Dellums (CA); Presentation of Awards by founding CBC members John Conyers, Jr. (MI) and William L. Clay (MO); Music by Noel Pointer, violinist, and Dr. Carol Yampolsky, pianist. GUESTS: Some 500 invited guests include: NGA Trustee John R. Stevenson; (See retiring and founding CBC members and speakers above.); Founding CBC members Augustus F. Hawkins (CA), Charles B. Rangel (NY), and Louis Stokes (OH); Retired CBC founding members Shirley Chisholm (NY), Charles C. Diggs (MI), and Parren Mitchell (MD) ; and many CBC members and other Congressional leaders. Others include: Ronald Brown, Democratic National Committee; Sharon Pratt Dixon, DC mayoral candidate; Benjamin L Hooks, NAACP; Dr. -

Hamer Biography

Fannie Lou Hamer (1917-1977) “All my life I’ve been sick and tired. Now I’m sick and tired of being sick and tired.” Fannie Lou Hamer was among the most significant participants in the struggle launched in the latter half of the twentieth century to achieve freedom and social justice for African Americans. Born October 6, 1917, in Montgomery County, Mississippi, she was the last of the twenty children of Lou Ella and James Townsend. They were sharecroppers, and since sharecropping generally bound workers to the land (a form of peonage), most sharecroppers were born poor, lived poor, and died poor. At age six Fannie Lou joined her parents in the cotton fields. By the time she was twelve, she was forced to drop out of school and work full time to help support her family. At age 27 she married another sharecropper named Perry “Pap” Hamer. In August 1962, Mrs. Hamer attended a meeting of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) in her hometown, Ruleville, Mississippi. This is where she made the fateful decision to attempt to register to vote. For this decision she was forced by her landlord to leave the plantation where she worked. In June the following year, she and several SNCC colleagues were brutally beaten in a Winona, Mississippi jail by law enforcement officers. This beating left her blind in her left eye and her kidneys permanently damaged. Mrs. Hamer’s historic presence in Atlantic City at the 1964 national convention of the Democratic Party brought national prominence with her electrifying testimony before the convention’s credentials committee. -

Abstract Valeika, Kathryn Roberts

ABSTRACT VALEIKA, KATHRYN ROBERTS. Can These Rights Be Fulfilled?: The Planning, Participants, and Debates of the To Fulfill These Rights Conference, June 1-2, 1966. (Under the direction of Dr. Blair LM Kelley.) On June 1 and 2, 1966, the White House sponsored the “To Fulfill These Rights Conference” in Washington, D.C. Following a year of planning by a council of civil rights activists, government officials, and big business and labor leaders, roughly 2500 people from diverse backgrounds and civil rights experiences attended the conference. Previously neglected by other historians, the conference and its planning reveal two important and related dynamics of the movement: the shifting alliances among civil rights leaders and the re-examination of civil rights goals and strategies. In particular, debates over the conference’s list of invitees, format, and procedures capture disagreements between established civil rights leaders, the White House, and labor and business leaders over who would, or could, direct the next phase of the civil rights movement. Secondly, conference debates on the reach of federal power, affirmative action, Vietnam, the expansion of the movement, fears of imminent violence, and the emergence of Black Power reveal the conflicting ideas that would create deep divisions between activists, liberals, and the federal government in the late 1960s and years to come. Can These Rights Be Fulfilled?: The Planning, Participants, and Debates of the To Fulfill These Rights Conference, June 1-2, 1966 by Kathryn Roberts Valeika A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of North Carolina State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts History Raleigh, North Carolina 2009 APPROVED BY: _______________________________ ______________________________ Dr. -

A Summary of the Contributions of Four Key African American Female Figures of the Civil Rights Movement

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 12-1994 A Summary of the Contributions of Four Key African American Female Figures of the Civil Rights Movement Michelle Margaret Viera Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Viera, Michelle Margaret, "A Summary of the Contributions of Four Key African American Female Figures of the Civil Rights Movement" (1994). Master's Theses. 3834. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/3834 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A SUMMARY OF THE CONTRIBUTIONS OF FOUR KEY AFRICAN AMERICAN FEMALE FIGURES OF THE CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT by Michelle Margaret Viera A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of History Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan December 1994 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My appreciation is extended to several special people; without their support this thesis could not have become a reality. First, I am most grateful to Dr. Henry Davis, chair of my thesis committee, for his encouragement and sus tained interest in my scholarship. Second, I would like to thank the other members of the committee, Dr. Benjamin Wilson and Dr. Bruce Haight, profes sors at Western Michigan University. I am deeply indebted to Alice Lamar, who spent tireless hours editing and re-typing to ensure this project was completed. -

Women in the Modern Civil Rights Movement

Women in the Modern Civil Rights Movement Introduction Research Questions Who comes to mind when considering the Modern Civil Rights Movement (MCRM) during 1954 - 1965? Is it one of the big three personalities: Martin Luther to Consider King Jr., Malcolm X, or Rosa Parks? Or perhaps it is John Lewis, Stokely Who were some of the women Carmichael, James Baldwin, Thurgood Marshall, Ralph Abernathy, or Medgar leaders of the Modern Civil Evers. What about the names of Septima Poinsette Clark, Ella Baker, Diane Rights Movement in your local town, city or state? Nash, Daisy Bates, Fannie Lou Hamer, Ruby Bridges, or Claudette Colvin? What makes the two groups different? Why might the first group be more familiar than What were the expected gender the latter? A brief look at one of the most visible events during the MCRM, the roles in 1950s - 1960s America? March on Washington, can help shed light on this question. Did these roles vary in different racial and ethnic communities? How would these gender roles On August 28, 1963, over 250,000 men, women, and children of various classes, effect the MCRM? ethnicities, backgrounds, and religions beliefs journeyed to Washington D.C. to march for civil rights. The goals of the March included a push for a Who were the "Big Six" of the comprehensive civil rights bill, ending segregation in public schools, protecting MCRM? What were their voting rights, and protecting employment discrimination. The March produced one individual views toward women of the most iconic speeches of the MCRM, Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a in the movement? Dream" speech, and helped paved the way for the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and How were the ideas of gender the Voting Rights Act of 1965. -

Martin Luther and Coretta Scott King Library

At James Madison University Martin Luther and Coretta Scott King Library Book Catalog Abu-Nimer, Mohammed. 2003. Nonviolence and Peace Building in Islam: Theory and Practice. Gainesville: University Press of Florida. Ackerman, Peter and Jack Duvall. 2000. A Force More Powerful: A Century of Nonviolent Conflict. New York: Palgrave. Agrawal, A. N. 2005. The Rupa Book of Gandhi Quiz. New Delhi: Rupa. Alter, Joseph S. 2000. Gandhi’s Body: Sex, Diet, and the Politics of Nationalism. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. Andrews, Charles F. 2003. Mahatma Gandhi: His Life and Ideas. Woodstock: First SkyLight Paths Publishing. Arendt, Hannah. 1970. On Violence. New York: Harcourt Brace. Arnold, David. 2001. Gandhi: Profiles in Power. Harlow: Pearson Education. Ashe, Geoffrey. 1968. Gandhi: A Biography. New York: Cooper Square Press. Attenborough, Richard, ed. 1982. The Words of Gandhi. New York: Newmarket Press. Badruddin. 2003. Global Peace and Anti-Nuclear Movements. New Delhi: Mittal Publications. Balagangadhara, S. N. 2005. “The Heathen in His Blindness”: Asia, the West and the Dynamic of Religion. New Delhi: Manohar. Barak, Gregg. 2003. Violence and Nonviolence: Pathways to Understanding. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications. 2 / King Library Book Catalog Barash, David P., ed. 2000. Approaches to Peace: A Reader in Peace Studies. New York: Oxford University Press. Batra, Shakti, ed. N.d. The Quintessence of Gandhi in His Own Words. New Delhi: Madhu Muskan Publications. Betai, Ramesh S. 2002. Gita and Gandhiji. New Delhi: Gyan Publishing. Bharucha, Rustom. 1993. The Question of Faith. New Delhi: Orient Longman. Bloom, Irene, J. Paul Martin, and Wayne L. Proudfoot, eds. 1996. Religious Diversity and Human Rights. -

Civil Rights TRANSCRIPT

Communication Matters: The NCA Podcast | TRANSCRIPT Episode 20: Civil Rights Episode **Please note: This is a rough transcription of this audio podcast. This transcript is not edited for spelling, grammar, or punctuation.** Participants: Trevor Parry-Giles Robin Boylorn Maegan Parker Brooks Armond Towns [Audio Length: 0:54:37] RECORDING BEGINS Trevor Parry-Giles: Welcome to Communication Matters, the NCA podcast. I'm Trevor Parry-Giles, the Executive Director of the National Communication Association. The National Communication Association is the preeminent scholarly association devoted to the study and teaching of communication. Founded in 1914, NCA is a thriving group of thousands from across the nation and around the world who are committed to a collective mission to advance communication as an academic discipline. In keeping with NCA's mission to advance the discipline of communication, NCA has developed this podcast series to expand the reach of our member scholars’ work and perspectives. Introduction: This is Communication Matters, the NCA podcast. Robin Boylorn: At the basic level for me, diversity is a very basic general thing that everybody should be doing anyway. It really should be aspirational at this point. But how can we unpack it and deconstruct it a bit more without putting additional invisible labor on faculty and scholars of color? Trevor Parry-Giles: On today's episode of Communication Matters, the NCA podcast, we're addressing civil rights and the passing of the civil rights generation, the new civil rights generation and issues related to diversity, equity and inclusion. Professors Robin M. Boylorn, Maegan Parker Brooks and Armond Towns join me today for this really timely and interesting conversation. -

Transafrica Board of Directors

TRANSAFRICA BOARD OF DIRECTORS The Honorable Richard Gordon Hatcher Chairman Harry Belafonte William Lucy Reverend Charles Cobb Dr. Leslie Mclemore Courtland Cox Marc Stepp The Honorable Ronald Dellums The Honorable Percy Sutton Dr. Dorothy Height Dr. James Turner Dr. Sylvia Hill Reverend Wyatt Tee Walker Dr. Willard Johnson The Honorable Maxine Waters Robert White Randall Robinson Executive Director SPONSORS African and Caribbean Diplomatic Corps His Excellency Jose Luis Fernandes Lopes His Excellency Jean Robert Odgaza His Excellency Willem A. Udenhout Cape Verde Gabon Sun·nanze His Excellency Abdellah Ould Daddah His Excellency Charles Gomis His Excellency Dr. Paul John Firmino Lusaka Mauritania Cote d 'luoire Zambia His Excellency Keith Johnson Her Excellency Eugenia A. Wordsworth-Stevenson His Excellency Stanislaus Chigwedere Jamaica li/x>ria Zimbabwe His Excellency P'dul Pondi His Excellency Sir William Douglas His Excellency Jean Pierre Sohahong-Kombet Cameroon Barbados Central African Republic His Excellency Chitmansing J esseramsing His Excellency Alhaji Hamzat Ahmadu His Excellency Pierrot]. Rajaonarivelo Mauritius Nigeria Madagascar His Excellency Dr. Cedric Hilburn Grant His Excellency Ousman Ahmadou Sallah His Excellency Abdalla A. Abdalla Guyana The Gambia Sudan His Excellency Edmund Hawkins Lake His Excellency Aloys Uwimana His Excellency Mohamed Toure Antigua and BarlJuda Rwanda Mali His Excellency Ellom-Kodjo Schuppius His Excellency Roble Olhaye His Excellency Moussa Sangare Togo Djibouti Guinea His Excellency Mahamat -

Biographical Sketch of Fannie Lou Hamer

ERICA AM F E IN C D OI YOUR V Fannie Lou Hamer: A Biographical Sketch By Maegan Parker Brooks, PhD “I question America. Is this America, the land of the free and the home of the brave, where we have to sleep with our telephones off the hook because our lives be threatened daily, because we want to live as decent human beings, in America?” With this critical question, delivered at the 1964 Democratic National Convention, Fannie Lou Hamer became revered across the nation. Malcolm X referred to her as the “country’s number one freedom fighting woman” and rumor has it Martin Luther King, Jr—though he loved her dearly— feared being upstaged by Hamer’s soul-stirring speeches. Over her lifetime (1917-1977), Fannie Lou Hamer traveled from the Delta of Mississippi to the Atlantic City Boardwalk, from Washington, D.C. to Washington State, from Madison, Wisconsin to Conakry, Guinea—always proclaiming the social gospel that all human beings are created equal and that all people are entitled to basic rights of food, FIGURE 1: Fannie Lou Hamer addresses the shelter, dignity, and a voice in the government to 1964 Democratic National Convention. which they belong. Fannie Lou Hamer held strong convictions, but she was no idealist. Born the twentieth child of James Lee and Lou Ella Townsend, Fannie Lou and her large family struggled to survive as sharecroppers on plantations controlled by Whites. As an outgrowth of slavery, the sharecropping system was largely designed to keep Black people indebted to White landowners. This economic control held social and political implications as well. -

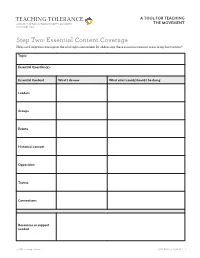

Step Two: Essential Content Coverage How Can I Improve Coverage of the Civil Rights Movement by Addressing These Essential Content Areas in My Instruction?

TEACHING TOLERANCE A TOOL FOR TEACHING A PROJECT OF THE SOUTHERN POVERTY LAW CENTER THE MOVEMENT TOLERANCE.ORG Step Two: Essential Content Coverage How can I improve coverage of the civil rights movement by addressing these essential content areas in my instruction? Topic: Essential Question(s): Essential Content What I do now What else I could/should I be doing Leaders Groups Events Historical context Opposition Tactics Connections Resources or support needed © 2014 Teaching Tolerance CIVIL RIGHTS DONE RIGHT TEACHING TOLERANCE A TOOL FOR TEACHING A PROJECT OF THE SOUTHERN POVERTY LAW CENTER THE MOVEMENT TOLERANCE.ORG Step Two: Essential Content Coverage (SAMPLE) How can I improve coverage of the civil rights movement by addressing these essential content areas in my instruction? Topic: 1963 March on Washington Essential Question(s): How do the events and speeches of the 1963 March on Washington illustrate the characteristics of the civil rights movement as a whole? Essential Content What I do now What else I could/should be doing Leaders Martin Luther King Jr., Bayard Rustin, James Farmer, John Lewis, Roy A. Philip Randolph Wilkins, Whitney Young, Dorothy Height Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), Student Nonviolent Groups Coordinating Committee (SNCC), Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP), National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), National Urban League (NUL), Negro American Labor Council (NALC) The 1963 March on Washington was one of the most visible and influential Some 250,000 people were present for the March Events events of the civil rights movement. Martin Luther on Washington. They marched from the Washington King Jr. -

FANNIE LOU HAMER a Historical Time Line

FANNIE LOU HAMER A Historical Time Line October 6, 1917 Fannie Lou Townsend is born in Montgomery County, Mississippi. May 21, 1918 The U.S. House of Representatives passes the Nineteenth Amendment to the Constitution, granting women the right to vote. February 14, 1920 The League of Women Voters is founded, with the goal of giving women a stronger role in public affairs. May 2, 1927 In Buck v. Bell, by a vote of 8–1, the U.S. Supreme Court affirms the constitutionality of Virginia’s law allowing state-enforced sterilization. In 1962, while undergoing surgery to remove a small tumor, Hamer will receive a hysterectomy without her consent or prior knowledge. 1944 Fannie Lou Townsend marries Perry “Pap” Hamer. May 17, 1954 In Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas, the U.S. Supreme Court declares school segregation unconstitutional. May 6, 1960 The Civil Rights Act of 1960 is signed into law by President Eisenhower; it includes measures against discriminatory voting practices. 1963 Hamer finally succeeds in registering to vote. From June 9–12, she is arrested and brutally beaten while in police custody. 1964 Hamer runs for Congress in the Mississippi state Democratic primary. On June 19, after an eighty-three-day filibuster, the U.S. Senate passes the Civil Rights Act of 1964, prohibiting discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, or national origin. On August 22, in a televised appearance, Hamer addresses the Democratic National Convention’s Credentials Committee about the problems she encountered in registration and her beating in jail. President Johnson calls a press conference at the same time as her speech to prevent her voice from being heard, but her speech is aired later by many television networks.