Folding Workbench

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TOOLS and EQUIPMENT Orthotic 561

TOOLS AND EQUIPMENT Orthotic 561 Tools Shoe Stretchers............................562 Brannock Measuring Device..................562 Mixing Bowls ..............................562 Aluminum Cast Mandrels ....................562 Laminating Fixtures.........................563 Vises and Yates Clamps.................563-564 Measuring Devices .....................564-567 Hex Sets and Balldrivers.................567-569 Screw and Drill Gages ......................569 Cutting Nippers ............................570 Plastering Tools............................571 Shears and Scissors ....................571-572 Blades, Knives and Surforms .............572-575 Rivets, Punch Sets and Eyelets ...........576-579 Reamers .................................579 Needle Kit ................................579 Deburring Tool.............................579 Rout-A-Burr ...............................579 Precision Oiler.............................580 Countersinks ..............................580 Adjustable Bits.............................580 Tools Ball Set Tool . 580 Micro Torches and Heat Guns ............580-582 Cast Spreaders and Cutters ..............583-584 Alignment Fixtures .........................584 Benders and Contouring Iron .............584-585 Equipment Carvers, Cutters and Routers.............585-588 Sanding Accessories............ 589-591, 601-603 Sewing and Patching Machines ...............592 Drill Press ................................593 Band Saws . .594-595 Dust Collectors ........................596-597 -

Headlok® and Spiderdrive® Are Registered Trademarks of OMG, Inc

® HeadLok PRODUCT DATA SPECIFICATIONS PRODUCT DESCRIPTION COATING The OMG HeadLok is a specialized, flat head OMG CR-10 corrosion resistant coating fastener engineered for a wide range of passes the corrosion requirements of FM panel applications including Structural Insu- Approval Standard 4470 and ETAG 006. lated Panels, Prefabricated Wall Panels, and APPLICATION USE Nailboard, and can also be used in wood, WITH structural concrete*, purlins*, corrugated Install the OMG HeadLok using a high torque, and structural steel substrates. low RPM screw gun. Bring underside of P the washer head flat to the surface. Do not FEATURES & BENEFITS overdrive. For steel substrates, proper point S • Three point and thread styles available style must be determined depending on the for fast installation. steel gauge thickness. W • Spade Point for use in in steel *For structural concrete, use the OMG SC HeadLok with spade points only. The fastener (18 - 22 ga.), structural concrete and DECK wood; must penetrate structural concrete decks a TYPES • Gimlet Point for use in dimensional minimum of 1-inch. Pre-drill using a 3/16-in. lumber; pilot hole at least 1/2-in. (13 mm) deeper than fastener embedment. • Drill Point for use in steel purlins PHYSICAL DATA** up to 3/16-in. thick. The 1/2-in. *For purlin attachment, use OMG HeadLok The data below is constant for each OMG HeadLok. with drill point only. drill point allows the fastener to be HEAD POINT STYLES SHANK drilled through the purlin before the *Prior to job-start, contact OMG to perform a .625" (15.87 mm) • Gimlet .190" (4.82 mm) threads engage. -

1. Hand Tools 3. Related Tools 4. Chisels 5. Hammer 6. Saw Terminology 7. Pliers Introduction

1 1. Hand Tools 2. Types 2.1 Hand tools 2.2 Hammer Drill 2.3 Rotary hammer drill 2.4 Cordless drills 2.5 Drill press 2.6 Geared head drill 2.7 Radial arm drill 2.8 Mill drill 3. Related tools 4. Chisels 4.1. Types 4.1.1 Woodworking chisels 4.1.1.1 Lathe tools 4.2 Metalworking chisels 4.2.1 Cold chisel 4.2.2 Hardy chisel 4.3 Stone chisels 4.4 Masonry chisels 4.4.1 Joint chisel 5. Hammer 5.1 Basic design and variations 5.2 The physics of hammering 5.2.1 Hammer as a force amplifier 5.2.2 Effect of the head's mass 5.2.3 Effect of the handle 5.3 War hammers 5.4 Symbolic hammers 6. Saw terminology 6.1 Types of saws 6.1.1 Hand saws 6.1.2. Back saws 6.1.3 Mechanically powered saws 6.1.4. Circular blade saws 6.1.5. Reciprocating blade saws 6.1.6..Continuous band 6.2. Types of saw blades and the cuts they make 6.3. Materials used for saws 7. Pliers Introduction 7.1. Design 7.2.Common types 7.2.1 Gripping pliers (used to improve grip) 7.2 2.Cutting pliers (used to sever or pinch off) 2 7.2.3 Crimping pliers 7.2.4 Rotational pliers 8. Common wrenches / spanners 8.1 Other general wrenches / spanners 8.2. Spe cialized wrenches / spanners 8.3. Spanners in popular culture 9. Hacksaw, surface plate, surface gauge, , vee-block, files 10. -

Powers-Tapper.Pdf

NEW CONCRETE SCREW TECHNOLOGY Tapper ®+ INSTALLATION PROCEDURES Using the proper diameter bit, drill a hole into the base material to a depth of at least 1/2” deeper than the embedment The required. A TAPPER+ drill bit Tapper+ is a must be used. Blow the hole clean of dust and other material. one-piece self-tapping concrete screw for use in a Select the TAPPER+ installation tool and drive socket to be used. variety of light to medium duty Insert the head of the TAPPER+ into the hex head socket or applications in base materials including Phillips head driver. Set the drill concrete, masonry and wood. It features motor to the “rotation only” a corrosion resistant Perma-Seal ® coating mode to install. and an optimized thread design for lower Place the point of the TAPPER+ through the fixture into the pre- installation torque. The screw also incorporates drilled hole and drive the anchor a gimlet drill point for wood base materials in one steady continuous motion until it is fully seated at the (no pre-drilling required). Tapper+ is available proper embedment. The driver in a variety of head styles and colors to match will automatically disengage from the head of the TAPPER+. the application. Note: Do not select a length that will result in an embedment into the base material which is greater than 2". Most concrete screw anchors cannot be Top Performance of properly driven to a depth of more than 2", especially the Tapper ®+ Sets a in denser base materials. New Standard for Concrete Screws Powers TAPPER ®+ ITW TAPCON ® VS. -

Berengario's Drill: Origin and Inspiration

Neurosurg Focus 36 (4):E7, 2014 ©AANS, 2014 Berengario’s drill: origin and inspiration MICHAEL A. CHORNEY, B.S., CHIRAG D. GANDHI, M.D., AND CHARLES J. PRESTIGIACOMO, M.D. Department of Neurological Surgery, Rutgers–New Jersey Medical School, Newark, New Jersey Craniotomies are among the oldest neurosurgical procedures, as evidenced by early human skulls discovered with holes in the calvaria. Though devices change, the principles to safely transgress the skull are identical. Modern neurosurgeons regularly use electric power drills in the operating theater; however, nonelectric trephining instru- ments remain trusted by professionals in certain emergent settings in the rare instance that an electric drill is unavail- able. Until the late Middle Ages, innovation in craniotomy instrumentation remained stunted without much docu- mented redesign. Jacopo Berengario da Carpi’s (c. 1457–1530 CE) text Tractatus de Fractura Calvae sive Cranei depicts a drill previously unseen in a medical volume. Written in 1518 CE, the book was motivated by defeat over the course of Lorenzo II de’Medici’s medical care. Berengario’s interchangeable bit with a compound brace (“vertibu- lum”), known today as the Hudson brace, symbolizes a pivotal device in neurosurgery and medical tool design. This drill permitted surgeons to stock multiple bits, perform the craniotomy faster, and decrease equipment costs during a period of increased incidence of cranial fractures, and thus the need for craniotomies, which was attributable to the introduction of gunpowder. The inspiration stemmed from a school of thought growing within a population of physi- cians trained as mathematicians, engineers, and astrologers prior to entering the medical profession. -

Power Tool Accessories and Hand Tools

Power Tool Accessories and Hand Tools IVY Classic Industries, Inc. PC1010 40 Plain Avenue • New Rochelle, NY 10801 USA Tel: 914-632-8200 Fax: 914-632-6449 800-435-3867 800-552-2997 www.ivyclassic.com e-mail: [email protected] IVY Classic Industries, Inc. We Meet Your Needs IVY Classic is dedicated to manufacturing a comprehensive, high-quality line of power tool accessories and hand tools for the contracting, industrial and DIY markets. All our tools are subject to strict quality-control procedures From Our to ensure they meet our exacting Humble standardsstandards.. Beginning We continually update our package IVY Wrought Iron Works designs to help you effectively was established in 1929 by promote IVY Classic products. an English blacksmith named We use the latest in packing Albert George Story. Many of his materials, and our product cards original tools are on display at are bar coded and clearly labeled IVY Classic Industries. Originally with valuable information to make the name IVY was chosen as it any job easier. was made up of three letters that were all straight lines. These We are very proud of our straight letters could easily be complete assortment of display cut into any IVY product before merchandisers throughout the the company could afford a product line. Our merchandisers steel letter punch. Today IVY are carefully arranged to include Classic Industries is still the best-selling items in an a family-owned-and-operated organized, space-saving layout. business continuing the traditions of Mr. Albert George Story. We Set Very High Standards 2 IVY Classic Industries, Inc. -

Tools and Their Uses NAVEDTRA 14256

NONRESIDENT TRAINING COURSE June 1992 Tools and Their Uses NAVEDTRA 14256 DISTRIBUTION STATEMENT A : Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited. Although the words “he,” “him,” and “his” are used sparingly in this course to enhance communication, they are not intended to be gender driven or to affront or discriminate against anyone. DISTRIBUTION STATEMENT A : Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited. NAVAL EDUCATION AND TRAINING PROGRAM MANAGEMENT SUPPORT ACTIVITY PENSACOLA, FLORIDA 32559-5000 ERRATA NO. 1 May 1993 Specific Instructions and Errata for Nonresident Training Course TOOLS AND THEIR USES 1. TO OBTAIN CREDIT FOR DELETED QUESTIONS, SHOW THIS ERRATA TO YOUR LOCAL-COURSE ADMINISTRATOR (ESO/SCORER). THE LOCAL COURSE ADMINISTRATOR (ESO/SCORER) IS DIRECTED TO CORRECT THE ANSWER KEY FOR THIS COURSE BY INDICATING THE QUESTIONS DELETED. 2. No attempt has been made to issue corrections for errors in typing, punctuation, etc., which will not affect your ability to answer the question. 3. Assignment Booklet Delete the following questions and write "Deleted" across all four of the boxes for that question: Question Question 2-7 5-43 2-54 5-46 PREFACE By enrolling in this self-study course, you have demonstrated a desire to improve yourself and the Navy. Remember, however, this self-study course is only one part of the total Navy training program. Practical experience, schools, selected reading, and your desire to succeed are also necessary to successfully round out a fully meaningful training program. THE COURSE: This self-study course is organized into subject matter areas, each containing learning objectives to help you determine what you should learn along with text and illustrations to help you understand the information. -

Woodworking in Estonia

WOODWORKING IN ESTONIA HISTORICAL SURVEY By Ants Viires Translated from Estonian by Mart Aru Published by Lost Art Press LLC in 2016 26 Greenbriar Ave., Fort Mitchell, KY 41017, USA Web: http://lostartpress.com Title: Woodworking in Estonia: Historical Survey Author: Ants Viires (1918-2015) Translator: Mart Aru Publisher: Christopher Schwarz Editor: Peter Follansbee Copy Editor: Megan Fitzpatrick Designer: Meghan Bates Index: Suzanne Ellison Distribution: John Hoffman Text and images are copyright © 2016 by Ants Viires (and his estate) ISBN: 978-0-9906230-9-0 First printing of this translated edition. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means including information storage and retrieval systems without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. This book was printed and bound in the United States. CONTENTS Introduction to the English Language Edition vii The Twisting Translation Tale ix Foreword to the Second Edition 1 INTRODUCTION 1. Literature, Materials & Methods 2 2. The Role Played by Woodwork in the Peasants’ Life 5 WOODWORK TECHNOLOGY 1. Timber 10 2. The Principal Tools 19 3. Processing Logs. Hollowing Work and Sealed Containers 81 4. Board Containers 96 5. Objects Made by Bending 127 6. Other Bending Work. Building Vehicles 148 7. The Production of Shingles and Other Small Objects 175 8. Turnery 186 9. Furniture Making and Other Carpentry Work 201 DIVISION OF LABOR IN THE VILLAGE 1. The Village Craftsman 215 2. Home Industry 234 FINAL CONCLUSIONS 283 Index 287 INTRODUCTION TO THE ENGLISH-LANGUAGE EDITION feel like Captain Pike. -

SIP Fasteners for Structural Insulated Panel & Nail Base Construction

SIP Fasteners For Structural Insulated Panel & Nail Base Construction APPLICATION TRUFAST® SIP Fasteners are specifically engineered for attaching offers three fastener styles for use in wood, corrugated steel and steel structural insulated panels (SIPs) and nail base panels to wood and members without pre-drilling! Contact your panel manufacturer or metal framing. Featuring a large, pancake head style with a 6-lobe distributor to ask for a test drive of a TRUFAST SIP Fastener and see why drive, TRUFAST SIP Fasteners drive quickly and smoothly , and draw they’re the #1 fastener in the SIP industry. panels securely without the need of a washer. And only TRUFAST PRODUCT FEATURES • Case-hardened and tempered for easy installation and long-term durability • Large diameter, low profile pancake head provides excellent pull-through resistance without the need for a washer while eliminating “telegraphing” on shingles, metal panels, and other roof surface materials • 6-lobe internal drive offers excellent bit engagement during installation, especially in high torque applications • Widest selection of fastener lengths in the industry for proper sizing to panel thickness • Choice of 3 thread/point styles for job-matched performance in wood, steel, or concrete/CMU substrates CODE APPROVALS & LISTINGS FM Global Miami-Dade County DrJ Certification CE European Technical State of Florida Technical Evaluation Report Approval ETA 19/0616 FL# 4500-R4 TER 1909-04 MATERIAL SPECIFICATIONS Material: Case-hardened & tempered carbon steel Manufacturing Location: Bryan, OH USA Coating: TRU-KOTE™ Epoxy E-coat (black) LEED® Eligible Recycled Content: 20% SIPTP Thread Point for Wood, Timber, and Concrete/CMU Applications SIPLD Light-Duty Drill Point for Corrugated Steel Deck, Wood, & Concrete/CMU Applications SIPHD Heavy-Duty Drill Point for Thick Steel Member Applications ALTENLOH, BRINCK & CO. -

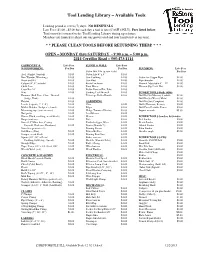

Tool Lending Library – Available Tools

Tool Lending Library – Available Tools Lending period is seven (7) days. NO RENEWALS Late Fees: $1.00 - $5.00 for each day a tool is late (CASH ONLY). Fees listed below . Tools must be returned to the Tool Lending Library during open hours. Members are limited to check out one power tool and four hand tools at one time. * * PLEASE CLEAN TOOLS BEFORE RETURNING THEM! * * * OPEN – MONDAY thru SATURDAY - 9:00 a.m. – 5:00 p.m. 2414 Cerrillos Road – 505-473-1114 CARPENTRY & Late Fees FLOOR & WALL Late Fees WOODWORKING Per Day Per Day PLUMBING Late Fees Cutter Wet Tile (power tools) Per Day Awl, (Gimlet, Scratch) $1.00 Cutter Tile 4" x 6" $1.00 Bar (Wonder, Wrecking) $1.00 Gun Caulking $1.00 Cutter for Copper Pipe $1.00 Brace and Bit $1.00 Gun Heat $1.00 Pipe threader $1.00 Caliper (4", 6” outside) $1.00 Knife Linoleum $1.00 Wrench Adjustable 6” – 12” $1.00 Chalk Line $1.00 Paint Mixer $1.00 Wrench Slip Lock-Nut $1.00 Crow Bar 24" $1.00 Roller Paint w/Ext. Pole $1.00 Files $1.00 Sanding Tool Drywall $1.00 POWER TOOLS Drills &Bits Hammer (Ball Peen, Claw, Drywall, Telescope Roller Handle $1.00 Drill Bit Set Masonry Carbide $1.00 Sedge, Tack) $1.00 Drill Bit Set Wood / Metal $1.00 Hatchet $1.00 GARDENING Drill Bit Set (Complete) $1.00 Levels (torpedo, 2’ 3’ 4’) $1.00 Claw $1.00 Drills (Hammer, Rotary) $5.00 Mallet (Rubber, Sculptor’s, hand) $1.00 Edger $1.00 Drill Press Portable Power $5.00 Measuring tape (various sizes) $1.00 Hedge Trimmer Electric $3.00 Impact wrench $5.00 Nail puller $1.00 Leaf Blower $5.00 Planes (Hand, molding, wood block) -

Hand Tool Identification

HAND TOOL IDENTIFICATION Left click or use the Roller on the mouse to navigate To help protect your privacy, PowerPoint prevented this external picture from being automatically downloaded. To download and display this picture, click Options in the Message Bar, and then click Enable external content. MEASURING TOOLS BENCH RULE TAPE MEASURE FOLDING EXTENTION LASER STEEL LONG TAPE RULE To help protect your privacy, PowerPoint prevented this external picture from being automatically downloaded. To download and display this picture, click Options in the Message Bar, and then click Enable external content. SAWS HACK SAW COPING SAW BACK SAW RIP SAW CROSSCUT SAW To help protect your privacy, PowerPoint prevented this external picture from being automatically downloaded. To download and display this picture, click Options in the Message Bar, and then click Enable external content. LAYOUT TOOLS T-BEVEL SPEED SQUARE TRY SQUARE FRAMING SQUARE COMBINATION SQUARE To help protect your privacy, PowerPoint prevented this external picture from being automatically downloaded. To download and display this picture, click Options in the Message Bar, and then click Enable external content. LAYOUT TOOLS CONTOUR GAUGE INSIDE CALIPERS OUTSIDE CALIPERS CHALK LINE PLUM BOB To help protect your privacy, PowerPoint prevented this external picture from being automatically downloaded. To download and display this picture, click Options in the Message Bar, and then click Enable external content. LEVELS LINE LEVEL TORPEDO LEVEL CARPENTERS, SPIRIT LEVEL LEVELS TRANSIT BUILDERS BUILDERS LEVEL, LEVEL TRIPOD, ROD PLANES BLOCK PLANE JACK PLANE SURFORM FASTENING TOOLS PHILLIPS SCRATCH AWL SCREWDRIVER EXTENSION PHILLIPS BIT TORQ BIT STANDARD SCREWDRIVER SQUARE BIT To help protect your privacy, PowerPoint prevented this external picture from being automatically downloaded. -

Handout 1.Tools

HANDOUT 1.TOOLS: A tool is an object made to help the man constructing, repairing, or modifying other objects. E.g.: Wrench Drill Hammer Screwdriver L We can classify them in tools and power tools, power tools are those that have a motor (e.g.: a drill) All the different tools have different uses, we have to use them properly for the use they have been designed. 1. Draw a tool you know, find the name and the use of it in English and Catalan and write it under your drawing. Use the dictionary and the help of your classmates and the teacher. English Catalan Name: Nom: Operation: Acció: 2. Now write the name of all the tools all the class has found: English Català Name Operation Nom Acció Wrench Turn Clau fixa Cargolar Miquel Llaràs Lesson 1-TOOLS HANDOUT 2.TOOLS TABLE: Here’s a list of the most common tools in the workshop of the school: Rasp hacksaw Coping saw handsaw gimlet clamp C-clamp pliers Needle-nose pliers Round nose pliers Wire stripping pliers shears Hammer Ball-peen hammer Nilon mallet Riveting tool Rubber mallet Wrench (spanner) Flat head screwdriver Hot glue gun Torx screwdriver Flat Round file Bench vice file k Drill allen key Adjustable spanner Miquel Llaràs Lesson 1-TOOLS HANDOUT 3. EMPTY TABLE: 3. Now hide the page you have been using before and in groups try to write all the names Miquel Llaràs Lesson 1-TOOLS HANDOUT 4.OPERATIONS: 1. These are different operations we can do with the tools in the workshop.