Oceans in Crisis—Human Garbage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pressions of Volcanic Rock Outcrops, in Situ Ments Sampled from Kamilo Beach

Kelly Jazvac Rock Record September 9 – October 15, 2017 FIERMAN presents Rock Record, a solo exhibition by Canadian artist Kelly Jazvac. Rock Record features found materials presented both as art objects and as scientific evidence that plastic pollution has irrevocably changed Earth. The show centers on plastiglomerate – a term collaboratively coined by Jazvac, geologist Patricia Corcoran, and oceanographer Charles Moore in 2013—a new type of stone first described on Kamilo Beach, Hawaii, and later identified on beaches around the globe. Plastiglomerate is a hybrid stone produced when plastic debris melts and fuses with naturally-found sediment such as sand, shells, rock, and wood. For several years, Jazvac has presented these stones in art galleries and museums, emphasizing their poetic, affective, and pedagogical potential. Through their simultaneously natural and artificial forms, each plastiglomerate works to visualize the dense entanglements of human consumption and the environments that adapt and react to our overwhelming presence. However, these stones are not simply, nor primarily, artworks. They are also scientific evidence of how anthropogenic materials are altering Earth’s geology, as explained by Jazvac, Corcoran, and Moore in a co-authored scientific paper published in 2014. They argue that plastiglomerate has the potential to sink into Earth’s strata: due to the increased density of this plastic-sediment fusion, as plastiglomerate becomes buried, so too will the material be preserved for centuries to come. Both Corcoran and Jazvac are founding members of an interdisciplinary research team that considers the ways in which art and culture can contribute to scientific research. This team works collaboratively to make largely unseen aspects of plastic pollution visible. -

SPECIAL PUBLICATION 6 the Effects of Marine Debris Caused by the Great Japan Tsunami of 2011

PICES SPECIAL PUBLICATION 6 The Effects of Marine Debris Caused by the Great Japan Tsunami of 2011 Editors: Cathryn Clarke Murray, Thomas W. Therriault, Hideaki Maki, and Nancy Wallace Authors: Stephen Ambagis, Rebecca Barnard, Alexander Bychkov, Deborah A. Carlton, James T. Carlton, Miguel Castrence, Andrew Chang, John W. Chapman, Anne Chung, Kristine Davidson, Ruth DiMaria, Jonathan B. Geller, Reva Gillman, Jan Hafner, Gayle I. Hansen, Takeaki Hanyuda, Stacey Havard, Hirofumi Hinata, Vanessa Hodes, Atsuhiko Isobe, Shin’ichiro Kako, Masafumi Kamachi, Tomoya Kataoka, Hisatsugu Kato, Hiroshi Kawai, Erica Keppel, Kristen Larson, Lauran Liggan, Sandra Lindstrom, Sherry Lippiatt, Katrina Lohan, Amy MacFadyen, Hideaki Maki, Michelle Marraffini, Nikolai Maximenko, Megan I. McCuller, Amber Meadows, Jessica A. Miller, Kirsten Moy, Cathryn Clarke Murray, Brian Neilson, Jocelyn C. Nelson, Katherine Newcomer, Michio Otani, Gregory M. Ruiz, Danielle Scriven, Brian P. Steves, Thomas W. Therriault, Brianna Tracy, Nancy C. Treneman, Nancy Wallace, and Taichi Yonezawa. Technical Editor: Rosalie Rutka Please cite this publication as: The views expressed in this volume are those of the participating scientists. Contributions were edited for Clarke Murray, C., Therriault, T.W., Maki, H., and Wallace, N. brevity, relevance, language, and style and any errors that [Eds.] 2019. The Effects of Marine Debris Caused by the were introduced were done so inadvertently. Great Japan Tsunami of 2011, PICES Special Publication 6, 278 pp. Published by: Project Designer: North Pacific Marine Science Organization (PICES) Lori Waters, Waters Biomedical Communications c/o Institute of Ocean Sciences Victoria, BC, Canada P.O. Box 6000, Sidney, BC, Canada V8L 4B2 Feedback: www.pices.int Comments on this volume are welcome and can be sent This publication is based on a report submitted to the via email to: [email protected] Ministry of the Environment, Government of Japan, in June 2017. -

Characterization of Microplastic and Mesoplastic Debris in Sediments from Kamilo Beach and Kahuku Beach, Hawai'i

Salem State University Digital Commons at Salem State University Biology Faculty Publications Biology 11-11-2016 Characterization of Microplastic and Mesoplastic Debris in Sediments from Kamilo Beach and Kahuku Beach, Hawai'i Alan M. Young Salem State University James A. Elliott Salem State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.salemstate.edu/biology_facpub Part of the Biology Commons, and the Marine Biology Commons Recommended Citation Young, Alan M. and Elliott, James A., "Characterization of Microplastic and Mesoplastic Debris in Sediments from Kamilo Beach and Kahuku Beach, Hawai'i" (2016). Biology Faculty Publications. 1. https://digitalcommons.salemstate.edu/biology_facpub/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Biology at Digital Commons at Salem State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Biology Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons at Salem State University. Marine Pollution Bulletin 113 (2016) 477–482 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Marine Pollution Bulletin journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/marpolbul Note Characterization of microplastic and mesoplastic debris in sediments from Kamilo Beach and Kahuku Beach, Hawai'i Alan M. Young ⁎, James A. Elliott Biology Department, Salem State University, 352 Lafayette Street, Salem, MA 01970, United States article info abstract Article history: Sediment samples were collected from two Hawai'ian beaches, Kahuku Beach on O'ahu and Kamilo Beach on the Received 21 September 2016 Big Island of Hawai'i. A total of 48,988 large microplastic and small mesoplastic (0.5–8 mm) particles were Received in revised form 7 November 2016 handpicked from the samples and sorted into four size classes (0.5–1 mm, 1–2 mm, 2–4mm,4–8 mm) and Accepted 9 November 2016 nine color categories. -

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Gyre Plastic : Science, Circulation and the Matter of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/21w9h64q Author De Wolff, Kim Publication Date 2014 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Gyre Plastic: Science, Circulation and the Matter of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Communication by Kim De Wolff Committee in charge: Professor Chandra Mukerji, Chair Professor Joseph Dumit Professor Kelly Gates Professor David Serlin Professor Charles Thorpe 2014 Copyright Kim De Wolff, 2014 All rights reserved. The Dissertation of Kim De Wolff is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Chair University of California, San Diego 2014 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page ........................................................................................................... iii Table of Contents ....................................................................................................... iv List of Figures ............................................................................................................ vi Acknowledgements .................................................................................................... ix Vita ............................................................................................................................ -

MARINE LITTER SOCIO-ECONOMIC STUDY FINAL VERSION: DECEMBER 2017 Recommended Citation: UN Environment (2017)

MARINE LITTER SOCIO-ECONOMIC STUDY FINAL VERSION: DECEMBER 2017 Recommended citation: UN Environment (2017). Marine Litter Socio Economic Study, United Nations Environment Programme, Nairobi. Kenya. Copyright © United Nations Environment Programme (UN Environment), 2017 ISBN No: 978-92-807-3701-1 Job No: DEP/2175/NA No use of this publication may be made for resale or any other commercial purpose whatsoever without prior permission in writing from the United Nations Environment Programme. Applications for such permission, with a statement of the purpose and extent of the reproduction, should be addressed to the Communication Division, UN Environment P.O. Box 30552, Nairobi, Kenya, [email protected]. The Government of Germany is gratefully acknowledged for providing the necessary funding that made the production of this publication “Marine Litter Socio Economic Study“ possible. Acknowledgements: Peer reviewers: Dr. Sarah Dudas (Vancouver Island University), Dr. Jesús Gago (Instituto Español de Oceanografía), Francois Galgani (IFREMER), Dr. Denise Hardesty (CSIRO), Gaëlle Haut (Surfrider Foundation), Heidi Savelli (UN Environment), Dr. Sunwook Hong (OSEAN), Dr. Peter Kershaw (GESAMP), Ross A. Klein (Cruise Junkie/ Memorial University of Newfoundland), Päivi Munne (Finnish Environment Institute), Dr. Sabine Pahl (Plymouth University), François Piccione (Surfrider Foundation), Emma Priestland (Seas at Risk), Jacinthe Séguin (Environment Canada), Kaisa Uusimaa (UN Environment) , Dr. Dick Vethaak (Deltares), Nancy Wallace (NOAA Federal) -

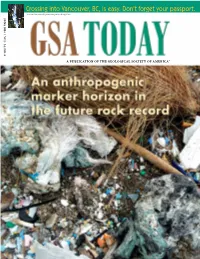

Crossing Into Vancouver, BC, Is Easy. Don't Forget Your Passport

Crossing into Vancouver, BC, is easy. Don’t forget your passport. Tourism Vancouver / Capilano Suspension Bridge Park. JUNE | VOL. 24, 2014 6 NO. A PUBLICATION OF THE GEOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF AMERICA® JUNE 2014 | VOLUME 24, NUMBER 6 Featured Article GSA TODAY (ISSN 1052-5173 USPS 0456-530) prints news and information for more than 26,000 GSA member readers and subscribing libraries, with 11 monthly issues (April/ May is a combined issue). GSA TODAY is published by The SCIENCE: Geological Society of America® Inc. (GSA) with offices at 3300 Penrose Place, Boulder, Colorado, USA, and a mail- 4 An anthropogenic marker horizon in the future ing address of P.O. Box 9140, Boulder, CO 80301-9140, USA. rock record GSA provides this and other forums for the presentation of diverse opinions and positions by scientists worldwide, Patricia L. Corcoran, Charles J. Moore, and regardless of race, citizenship, gender, sexual orientation, Kelly Jazvac religion, or political viewpoint. Opinions presented in this publication do not reflect official positions of the Society. Cover: Plastiglomerate fragments interspersed with plastic debris, © 2014 The Geological Society of America Inc. All rights organic material, and sand on Kamilo Beach, Hawaii. Photo by K. Jazvac. reserved. Copyright not claimed on content prepared See related article, p. 4–8. wholly by U.S. government employees within the scope of their employment. Individual scientists are hereby granted permission, without fees or request to GSA, to use a single figure, table, and/or brief paragraph of text in subsequent work and to make/print unlimited copies of items in GSA TODAY for noncommercial use in classrooms to further education and science. -

Written Testimony of Nicholas J. Mallos, Director, Trash Free Seas®, Ocean Conservancy Before the United States Senate Environm

Written Testimony of Nicholas J. Mallos, Director, Trash Free Seas®, Ocean Conservancy Before The United States Senate Environment and Public Works Committee Subcommittee on Fisheries, Water and Wildlife of the Environment and Public Works Hearing on Marine Debris and Wildlife: Impacts, Sources and Solutions May 17, 2016 Good morning. Thank you for inviting me to speak with you about the preponderance of plastics that are gathering in our seas and on our coastlines, affecting fisheries, marine mammals and potentially human health. My name is Nicholas Mallos, and I am director of Ocean Conservancy’s Trash Free Seas® program. Ocean Conservancy works across sectors, bringing businesses, conservationists and governments together to address systemic challenges and find lasting solutions. In all we do, we work with a range of partners to find scalable, implementable solutions that make a difference for the ocean and the communities that depend upon it. Ocean Conservancy is supported by a diverse funding base that currently includes individual donors, public and private foundations, corporations and U.S. government support. Plastic debris exists in every region of the ocean from consumer products floating in the ocean’s five major gyres to fibers buried in deep sea sediments and from microplastics embedded in Arctic sea ice to a wide diversity of plastics found on beaches worldwide. Today, I intend to convey the need for a new, interdisciplinary research agenda to better explain the scale and scope of the impact of plastics on marine ecosystems so that better-informed policies can confront these risks. Advancing this science requires a funding commitment from decision-makers who recognize that controlling plastic inputs to ocean ecosystems is a necessary condition for the ocean to provide the services upon which we depend. -

Plastiglomerate Are Many Things and Can Range from Rocky Outcrops to Lush Vegetation

The conditions that obtained when life had not yet emerged from the oceans have not subsequently changed a great deal for the cells of the human body, bathed by the primordial wave which continues to flow in the arteries. Our blood in fact has a 01/14 chemical composition analogous to that of the sea of our origins, from which the first living cells and the first multicellular beings derived the oxygen and the other elements necessary to life É The sea where living creatures were at one time immersed is now enclosed within their bodies. – Italo Calvino, Blood, Sea1 Kirsty Robertson What is a beach actually? It is marginalia, a footnote to the essay that is the ocean. Beaches Plastiglomerate are many things and can range from rocky outcrops to lush vegetation. But the sandy beach of popular imagination is made up of sediment, of particles coming from eroded coral reefs in the ocean, sediment from the sea floor, eroded sections of the continental shelf, or weathered and eroded rocks from nearby cliffs.2 In Hawai’i, volcanic basalt sometimes contributes to the mix, creating black beaches of small-to-tiny particles that are eroded by the constant, lapping wave action of the ocean. Beaches are far from sedentary. They are in constant motion, as wind and water wear away at rocks, coral, shells, and other matter. They also stretch across time as certain minerals, such as quartz and feldspar, are chemically stable and strong enough to last well through erosion, often n o 3 s forming the base of beaches millennia old. -

The Way of Macroplastic Through the Environment

environments Review The Way of Macroplastic through the Environment Simone Lechthaler 1,2,* , Kryss Waldschläger 1 , Georg Stauch 2 and Holger Schüttrumpf 1 1 Institute of Hydraulic Engineering and Water Resources Management, RWTH Aachen University, 52062 Aachen, Germany; [email protected] (K.W.); [email protected] (H.S.) 2 Department of Geography, Physical Geography and Geoecology, RWTH Aachen University, 52062 Aachen, Germany; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 28 August 2020; Accepted: 22 September 2020; Published: 24 September 2020 Abstract: With the focus on microplastic in current research, macroplastic is often not further considered. Thus, this review paper is the first to analyse the entry paths, accumulation zones, and sinks of macroplastic in the aquatic, terrestrial, and atmospheric environment by presenting transport paths and concentrations in the environment as well as related risks. This is done by applying the Source–Pathway–Receptor model on macroplastic in the environment. Based on this model, the life cycle of macroplastic is structurally described, and knowledge gaps are identified. Hence, current research aspects on macroplastic as well as a sound delimitation between macro- and microplastic that can be applied to future research are indicated. The results can be used as basic information for further research and show a qualitative assessment of the impact of macroplastic that ends up in the environment and accumulates there. Furthermore, the applied model allows for the first time a quantitative and structured approach to macroplastic in the environment. Keywords: macroplastic; life cycle; sources; sinks; transport paths; knowledge gaps 1. -

Plastics in the Marine Environment

PlasticsPlastics inin thethe PlasticPlastic SeaSea——thethe PacificPacific GyreGyre MarineMarine EnvironmentEnvironment AA CollaborativeCollaborative PresentationPresentation ALGALITA MARINE RESEARCH FOUNDATION Long Beach, CA. www.algalita.org Plastic!Plastic! --DurableDurable --LightweightLightweight --CheapCheap --VersatileVersatile Throwaway Living Life Magazine, 1955 PlasticPlastic isis PersistentPersistent •• PlasticPlastic doesndoesn’’tt biodegradebiodegrade •• PlasticPlastic photodegradesphotodegrades •• NoNo bacteriabacteria existsexists whichwhich cancan digestdigest plasticplastic polymerspolymers PlasticPlastic ProductionProduction inin thethe UnitedUnited StatesStates 2004 115 billion pounds (ACC, 2005) 1992 60 billion pounds (EPA,1992) InIn aa ““ThrowawayThrowaway”” society,society, wherewhere isis ““AWAYAWAY””?? Of the more than 50 million tons of thermoplastics produced in the U.S. annually, 25%, or 12.5 ? million tons, is unaccounted for. (California Integrated Waste Management 25% Board, “Plastics White Paper” 2003) Municipal Recycled Waste 5% 50% Nine-fold increase of plastic in Durable Goods municipal waste in the U.S. 20% between 1970-2003 (USEPA, 2003) HereHere isis ““AWAYAWAY”” 60-80% of marine debris worldwide is plastic (Derraik, 2002) HAWAII Canada Canada England,EnglandEngland UK SwedenSweden United States JapanJapan Hawaii China Philippines Litter left by tourists Venezuela Floating plastic bag Antarctica Tanzania Philippines New ZealandBeach cleanup Venezuela Antarctica Tanzania Slide: Dr. Richard Thompson WhereWhere -

Small Plastic Debris Changes Water Movement and Heat Transfer Through Beach Sediments ⇑ Henry S

Marine Pollution Bulletin 62 (2011) 1708–1713 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Marine Pollution Bulletin journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/marpolbul Small plastic debris changes water movement and heat transfer through beach sediments ⇑ Henry S. Carson , Steven L. Colbert, Matthew J. Kaylor, Karla J. McDermid Marine Science Department, University of Hawai‘i at Hilo, 200 W. Kawili St., Hilo, HI 96720, United States article info abstract Keywords: We investigated the physical properties of beaches contaminated with plastic fragments. We compared Marine debris sediment cores from Hawai‘i Island’s Kamilo Beach, notable for plastic accumulation, to cores from a Microplastic nearby beach. Compared to the nearby beach, Kamilo sediments contained more plastics (up to 30.2% Permeability by weight), were coarser-grained, and were more permeable (t-test, p < 0.0001). 85% of the fragments Porosity were polyethylene, and 95% were concentrated in the top 15 cm of the cores. We constructed artificial Heat transfer cores of standardized grain size and varying plastic-to-sediment ratios. Adding plastic significantly Kamilo Beach, Hawaii, USA increased the permeability (ANOVA, p = 0.002), which was partially attributed to the fragments increas- ing the mean grain size. Sediments with plastic warmed more slowly (16% maximum decrease in thermal diffusivity), and reached lower maximum temperatures (21% maximum increase in heat capacity). These changes have a variety of potential effects on beach organisms, including those with temperature- dependent sex-determination such as sea turtle eggs. Ó 2011 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. 1. Introduction in beach sediment. We assess the depth of plastic fragments mixed into beach sediments, determine potential changes to water move- Although synthetic polymers have made incalculable contribu- ment and heat transfer due to these fragments, and speculate on tions to the quality of human life in the past century, their longevity how these changes affect beach-dwelling organisms. -

Hawaii's 2018 Section 303(D)

UNITED STATES ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY REGION IX 75 Hawthorne Street San Francisco, CA 94105-3901 OFFICE OF THE REGIONAL ADMINISTRATOR Bruce Anderson, Director Hawai‘i Department of Health Kinau Hale 1250 Punchbowl Street Honolulu, Hawai‘i 96813 Re: Hawai‘i 2018 List of Impaired Waters under Clean Water Act (CWA), Section 303(d) Dear Mr. Anderson: The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) appreciates the Hawai‘i Department of Health’s (HDOH) supplemental submission of May 27, 2020, in response to EPA’s withdrawal of certain aspects of Hawai‘i’s 2018 List of Impaired Waters.1 EPA has carefully reviewed Hawai‘i’s response, including the listing decisions, the assessment methodology, and supporting data and information to determine whether the State reasonably identified waters to be listed as impaired. Based on this analysis, EPA approves Hawai‘i’s decision not to list 17 of 19 waterbodies based on the State’s conclusion that the readily available data and information do not require the identification of those waterbodies as impaired. While EPA does not agree with some of Hawai‘i’s specific reasoning for not listing, the State’s decision not to list these waterbodies is reasonable. EPA disapproves the State’s decision not to list the Kamilo Beach and Tern Island waterbodies because the existing and readily available data and information for those waterbodies indicate that they are impaired by trash and the State’s decision is inconsistent with CWA Section 303(d) and EPA’s implementing regulations. Therefore, EPA is adding Kamilo Beach and Tern Island to Hawai‘i’s 2018 CWA Section 303(d) List for trash impairments of marine waters and marine bottom ecosystems designated uses.