Arnold A. Rogow. a Fatal Friendship: Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Happy Birthday!

THE THURSDAY, APRIL 1, 2021 Quote of the Day “That’s what I love about dance. It makes you happy, fully happy.” Although quite popular since the ~ Debbie Reynolds 19th century, the day is not a public holiday in any country (no kidding). Happy Birthday! 1998 – Burger King published a full-page advertisement in USA Debbie Reynolds (1932–2016) was Today introducing the “Left-Handed a mega-talented American actress, Whopper.” All the condiments singer, and dancer. The acclaimed were rotated 180 degrees for the entertainer was first noticed at a benefit of left-handed customers. beauty pageant in 1948. Reynolds Thousands of customers requested was soon making movies and the burger. earned a nomination for a Golden Globe Award for Most Promising 2005 – A zoo in Tokyo announced Newcomer. She became a major force that it had discovered a remarkable in Hollywood musicals, including new species: a giant penguin called Singin’ In the Rain, Bundle of Joy, the Tonosama (Lord) penguin. With and The Unsinkable Molly Brown. much fanfare, the bird was revealed In 1969, The Debbie Reynolds Show to the public. As the cameras rolled, debuted on TV. The the other penguins lifted their beaks iconic star continued and gazed up at the purported Lord, to perform in film, but then walked away disinterested theater, and TV well when he took off his penguin mask into her 80s. Her and revealed himself to be the daughter was actress zoo director. Carrie Fisher. ©ActivityConnection.com – The Daily Chronicles (CAN) HURSDAY PRIL T , A 1, 2021 Today is April Fools’ Day, also known as April fish day in some parts of Europe. -

Texts and Other Fictions in Gore Vidalâ•Žs Burr

Studies in English, New Series Volume 11 Volumes 11-12 Article 29 1993 Texts and Other Fictions in Gore Vidal’s Burr Thomas Gladsky Central Missouri State University Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/studies_eng_new Part of the American Literature Commons Recommended Citation Gladsky, Thomas (1993) "Texts and Other Fictions in Gore Vidal’s Burr," Studies in English, New Series: Vol. 11 , Article 29. Available at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/studies_eng_new/vol11/iss1/29 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Studies in English at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in English, New Series by an authorized editor of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Gladsky: Texts and Other Fictions in Gore Vidal’s Burr TEXTS AND OTHER FICTIONS IN GORE VIDAL’S BURR Thomas Gladsky Central Missouri State University Over the years, Gore Vidal has campaigned furiously against theorists and writers of the new novel who, according to Vidal, “have attempted to change not only the form of the novel but the relationship between book and reader” (“French Letters” 67). In his essays, he has condemned the “misdirected” efforts of writers such as Donald Barthelme, John Gardner, Thomas Pynchon, John Barth, William Gass, and all those who come equipped with “formulas, theorems, signs, and diagrams because words have once again failed them” (“American Plastic” 102). In comparison, Vidal presents himself as a literary conservative, a defender of traditional form in fiction even though his own novels betray his willingness to penetrate beyond words and to experiment with form, especially in his series of historical novels. -

Treason Trial of Aaron Burr Before Chief Justice Marshall

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Master's Theses Theses and Dissertations 1942 Treason Trial of Aaron Burr before Chief Justice Marshall Aurelio Albert Porcelli Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Porcelli, Aurelio Albert, "Treason Trial of Aaron Burr before Chief Justice Marshall" (1942). Master's Theses. 687. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses/687 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1942 Aurelio Albert Porcelli .TREASON TRilL OF AARON BURR BEFORE CHIEF JUSTICE KA.RSHALL By AURELIO ALBERT PORCELLI A THESIS SUBJfiTTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OJ' mE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN LOYOLA UNIVERSITY .roD 1942 • 0 0 I f E B T S PAGE FOBEW.ARD • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 111 CHAPTER I EARLY LIFE OF llRO:N BURR • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • l II BURR AND JEFF.ERSOB ••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 24 III WES!ERN ADVDTURE OF BURR •••••••••••••••••••• 50 IV BURR INDICTED FOR !REASOB •••••••••••••••••••• 75 V !HE TRIAL •.•••••••••••••••• • ••••••••••• • •••• •, 105 VI CHIEF JUSTICE lfA.RSlU.LL AND THE TRIAL ....... .. 130 VII JIA.RSHALJ.- JURIST OR POLITICIAN? ••••••••••••• 142 BIBLIOGRAPHY ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 154 FOREWORD The period during which Thomas Jefferson, John Marshall, and Aaron Burr were public men was, perhaps, the most interest ing in the history of the United States. -

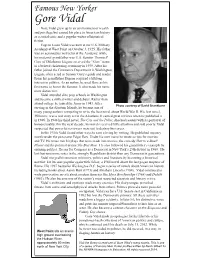

Gore Vidal Grew up in an Environment of Wealth and Privilege but Earned His Place in American History As a Social Critic and a Popular Writer of Historical Ction

Gore Vidal grew up in an environment of wealth and privilege but earned his place in American history as a social critic and a popular writer of historical ction. Eugene Louis Vidal was born at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point on October 3, 1925. His father was an aeronautics instructor at the Academy, while his maternal grandfather was U.S. Senator Thomas P. Gore of Oklahoma. Eugene received the “Gore” name in a belated christening ceremony in 1939. After his father joined the Commerce Department in Washington, Eugene often acted as Senator Gore’s guide and reader. From his grandfather Eugene acquired a lifelong interest in politics. As an author, he used Gore as his rst name to honor the Senator. It also made his name more distinctive. Vidal attended elite prep schools in Washington and became a skilled writer and debater. Rather than attend college he joined the Army in 1943. After Photo courtesy of David Shankbone serving in the Aleutian Islands, he became one of many young authors competing to write the best novel about World War II. His rst novel, Williwaw, was a war story set in the Aleutians. It earned great reviews when he published it in 1946. In 1948 his third novel, The City and the Pillar, shocked readers with its portrayal of homosexuality. For the next decade, his novels received little attention and sold poorly. Vidal suspected that powerful reviewers were out to destroy his career. In the 1950s Vidal found other ways to earn a living by writing. He published mystery novels under the pen-name Edgar Box. -

The DUEL the PARALLEL LIVES of ALEXANDER HAMILTON & AARON BURR

The DUEL THE PARALLEL LIVES OF ALEXANDER HAMILTON & AARON BURR BY JUDITH ST. GEORGE Teacher’s Edition The Duel: The Parallel Lives of JLG Reading Guide Copyright © 2009 Alexander Hamilton & Aaron Burr Junior Library Guild By Judith St. George 7858 Industrial Parkway Published by Viking/Penguin Group Plain City, OH 43064 Copyright © 2009 by Judith St. George www.juniorlibraryguild.com ISBN: 978-1-93612-900-3 ISBN: 978-0-670-01124-7 Copyright © 2009 Junior Library Guild/Media Source, Inc. 0 About JLG Guides Junior Library Guild selects the best new hardcover children’s and YA books being published in the U.S. and makes them available to libraries and schools, often before the books are available from anyone else. Timeliness and value mark the mission of JLG: to be the librarian’s partner. But how can JLG help librarians be partners with classroom teachers? With JLG Guides. JLG Guides are activity and reading guides written by people with experience in both children’s and educational publishing—in fact, many of them are former librarians or teachers. The JLG Guides are made up of activity guides for younger readers (grades K–3) and reading guides for older readers (grades 4–12), with some overlap occurring in grades 3 and 4. All guides are written with national and state standards as guidelines. Activity guides focus on providing activities that support specific reading standards; reading guides support various standards (reading, language arts, social studies, science, etc.), depending on the genre and topic of the book itself. JLG Guides can be used both for whole class instruction and for individual students. -

Aaron Burr - Patriot, Opportunist Or Scoundrel?

Denver Law Review Volume 19 Issue 8 Article 2 July 2021 Aaron Burr - Patriot, Opportunist or Scoundrel? Albert E. Sherlock Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/dlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Albert E. Sherlock, Aaron Burr - Patriot, Opportunist or Scoundrel?, 19 Dicta 187 (1942). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Denver Law Review at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Denver Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. Aaron Burr- Patriot, Opportunist or Scoundrel? By ALBERT E. SHERLOCK* Not at least since the time of the Whiskey Rebellion, until July of this year, has an American been convicted of treason. But the recent conviction of German-born Max Stephan of the highest crime in the land causes us to reflect on some of the incidents leading up to a more famous charge of the same crime-the indictment and trial of Aaron Burr. The trial occurred in Richmond, "a pleasure-loving place, famous for its conviviality-when the legislature was in session, a five-gallon of toddy stood ready for all comers every afternoon at the governor's house-for its horse races, and its beautiful women; exactly the place to appreciate the address, the wit, the accomplishments, of a man like Burr."' Against this background moved such figures as Thomas Jefferson, John Marshall, General James Wilkinson, Andrew Jackson, Theodosia Burr, Henry Clay, Harmon Blennerhassett, Benedict Arnold and John Wickham. -

Read the Complete Excerpt (PDF)

1 The Dark Star of the Founding n early 1800, at the dawn of a new century, Aaron Burr was on every short list of men who could become president of the United States. IHe was the most prominent Northern leader of the Republican party, which was poised to win the national elections that fall. As an emerging po- litical star, he seemed fated to shape the infant republic as it struggled for its place in a world of warring monarchies and despotisms. Burr had reached this extraordinarily favorable position by measured steps. From an early age, Burr preferred to advance on his own careful terms, beholden to no one. He had been just old enough to join the fight for independence from Britain. In 1776, when the Continental Congress issued the Declaration of Independence, the twenty-year-old Burr served as a lieutenant colonel in the Continental Army. When General George Wash- ington picked him as a personal aide, Burr swiftly lateraled into another assignment, out from under the great man’s shadow. When the Constitu- tional Convention met in 1787 to create a new government, Burr avoided the highly charged debates, building his New York law practice and local political standing. When the new Congress convened in 1789 and George Washington assembled the first government under the Constitution, Burr 3 4 AMERICAN EMPEROR served in the New York State government. Yet by 1800, Burr was a leading contender for the highest national offices. Writing some years later, former president John Adams struggled to ex- plain Burr’s rise. -

Aaron Burr: Villain to Hero Upgrade

Aaron Burr: Villain to Hero Upgrade Barbara Pralat Honors Thesis Advisors: Susan Lewis and Lou Roper Abstract: The research project explores the historiography surrounding Aaron Burr. For most of United States history, he has been vilified as a traitor to the nation and the murderer of Alexander Hamilton. However, Aaron Burr’s reputation has been questioned through Gore Vidal’s novel: Burr, published in 1973, which humanizes Burr without taking away from his notorious reputation. Nancy Isenberg’s historical biography: Fallen Founder published in 2007, which explores Burr as a feminist and looking at the accusations against Burr in the political world. More recently the musical Hamilton by Lin Manuel Miranda, explores Burr as Hamilton’s first friend and someone who is sympathetic and wants to get ahead in life. Using both primary and secondary sources to trace the history of Burr’s reputation and to show if Aaron Burr is really a villain, based on his character and career. Included in the research is highlights of Aaron Burr’s life and events that led to his reputation being portrayed as negative. The paper explores how one of America’s most notorious founding fathers gained such a bad reputation and if he deserves this reputation or if he deserves a better reputation and belongs with the other founding fathers. Key Words: History, Aaron Burr, Founding Fathers, American History, Alexander Hamilton. Intro: Aaron Burr has been known for many things: being a vice president, a war hero, a murderer, a traitor, a lawyer, and a feminist. In 1804, Aaron Burr killed Alexander Hamilton in a duel, thus destroying his chances of a further political career in America. -

Gore Vıdal's Hıstorıographıc Metafıctıons in the Narratıves Of

Hacettepe University Graduate School of Social Sciences Department of American Culture and Literature FACT, FICTION, FACT-IN-FICTION: GORE VIDAL’S HISTORIOGRAPHIC METAFICTIONS IN THE NARRATIVES OF EMPIRE Saniye Çancı Çalı şaneller Ph. D. Dissertation Ankara, 2013 FACT, FICTION, FACT-IN-FICTION: GORE VIDAL’S HISTORIOGRAPHIC METAFICTIONS IN THE NARRATIVES OF EMPIRE Saniye Çancı Çalı şaneller Hacettepe University Graduate School of Social Sciences Department of American Culture and Literature Ph. D. Dissertation Ankara, 2013 iii To my beloved Tarkan… iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Writing a dissertation is a collective effort, and I have been privileged in having had Assoc. Prof. Dr. Bilge Mutluay Çetinta ş as my advisor without whom this dissertation could not have been written. Her knowledge in the field has greatly nurtured this study. Her unending support, tolerance, and patience kept me going in the course of writing my dissertation. I would also like to extend my sincere gratitude to Prof. Dr. N. Belgin Elbir who has contributed a lot to my work; to Assoc. Prof. Dr. Meldan Tanrısal who has continuously encouraged and helped me in this process; to Assoc. Prof. Dr. Nur Gökalp Akkerman who has always been generous in providing full support for me; and to Assoc. Prof. Dr. Ufuk Özda ğ for her contributions to my academic life. I am also thankful to Assist. Prof. Dr. Barı ş Gümü şba ş, Assist. Prof. Dr. Ayça Germen, Assoc. Prof. Dr. Tanfer Emin Tunç, Dr. Özge Özbek Akıman, and Res. Assist. Merve Özman for their support. I also wish to extend my deepest thanks to Assoc. Prof. -

Alexander Hamilton Exhibition Tour Itinerary

Alexander Hamilton Exhibition Tour Itinerary Important exhibit display information: The first date of your exhibit display period is a Thursday. The shipper will deliver the exhibit to you no later than Wednesday--the day before. You can schedule programs for Thursday evening, but please do not plan programs early on Thursday in case of delivery problems (they are rare, but do happen). Friday openings and programs are the best--you may open the exhibit whenever it suits your local schedule. This exhibit will take 2-3 people approximately 2-3 hours to unpack and set up. The last date in your exhibition period is a Friday, which should be the closing date for the exhibition (you may close the exhibit earlier if you wish). Because there is limited time available to get the exhibition from one site to another, libraries should have the exhibition dismantled and ready for pick-up on the Monday after the exhibition closes. This does not mean the shipper will always pick up the exhibit on Monday, but the exhibit should be ready to go on Monday morning. Copy 1 Copy 2 2006 Jan. 12 – Feb. 24 Poughkeepsie NY Prince William VA Poughkeepsie PL Prince William PL March 9 – April 28 Burlington VT Towson MD Champlain College Towson University May 11 – June 23 Toms River NJ Clinton Township MI Ocean County Library Clinton-Macomb PL July 6 – August 18 Martinsburg WV Spring Lake MI Martinsburg-Berkeley Spring Lake District Lib. Co. PL August 31 – Oct. 13 Columbus OH Springfield, IL State Library of Ohio Illinois State Library Oct. -

The Poetics of Correction in Gore Vidal S and Saramago S *

Adriana Alves de Paula Martins The poetics of correction in Gore Vidal s and Saramago s * True history [...] is the final fiction. (Gore Vidal, Empire) Tudo quanto não for vida, é literatura, A história também, A história sobretudo1 (José Saramago, História do Cerco de Lisboa) Much of what we take to be true is often seriously wrong, and the way that it is wrong is more often worthy of investigation than the often trivial disagreed upon facts of the case. (Gore Vidal, Screening History) I In my doctoral dissertation I developed a typology of postmodern historical fiction that comprised four categories of novel that correspond to various discursive modulations of history: the historical novel, the supra-real fiction, the uchronian novel and the historiographic metafiction.2 The typology is informed by the issue of error, deformation, and correction proceeding from the awareness that all representations of the past are ideological constructs. This essay compares Gore Vidal s Burr (1973) and José Saramago s História do Cerco de Lisboa (1989) as two different types of post-modern historical fiction that rest on common preoccupations, while embodying distinct literary projects. Both novels belong to well-defined cycles within their authors novelistic production, namely cycles of novels that reflect upon the construction of national memory in their respective countries of birth. Before concentrating my attention on the selected corpus, it is necessary to present, even though in brief terms, the typology of post-modern historical fiction in order to explain the functionality of each one of its categories, since the issues of error, deformation, and correction, on the one hand, and the construction of national memory, on the other, are tackled in different ways within the framework of each category, thus producing distinct problematizing effects in the manipulation of historical accounts. -

Dueling As Politics: the Burr- Hamilton Duel

THE NEW-YORK JOURNAL OF AMERICAN HISTORY dueling as politics: the burr- hamilton duel Joanne B. Freeman n july 11, 1804, Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr fought what was to become the most famous duel in American history. This day of reckoning had been long approaching, for Hamilton had bitterly opposed Burr’s political career for fifteen years. Charismatic O men of great talent and ambition, the two had been thrust into competition with the opening of the national government and the sudden availability of new power, positions, and acclaim. Their rivalry continued even after they had been cast off the national stage and were competing in the more limited circle of New York State politics; by 1804, Burr had been summarily ejected from the u.s. vice presidency and Hamilton had self-destructed with a fool- hardy pamphlet attacking his own party’s candidate for president. Burr, however, seemed to have larger ambitions, courting Federalists throughout New England to unite behind him and march towards secession—or so Hamilton thought—and Burr’s first step on that path appeared to be the gubernatorial election of 1804. Horrified that Burr could become New York’s chief Federalist, corrupt the Federalist party, sabotage Hamilton’s influence, and possibly destroy the republic, Hamilton stepped up his opposition. Anxious to discredit Burr, he attacked his private character, denouncing him as “one who ought not to be trusted with the reins of government.”1 Burr was keenly aware of Hamilton’s opposition and was no long- er willing to overlook it, for the 1804 election was his last hope for political power.