Burr: an American Conspiracy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

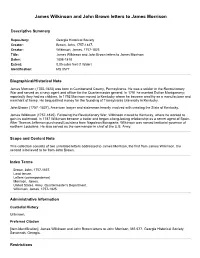

James Wilkinson and John Brown Letters to James Morrison

James Wilkinson and John Brown letters to James Morrison Descriptive Summary Repository: Georgia Historical Society Creator: Brown, John, 1757-1837. Creator: Wilkinson, James, 1757-1825. Title: James Wilkinson and John Brown letters to James Morrison Dates: 1808-1818 Extent: 0.05 cubic feet (1 folder) Identification: MS 0577 Biographical/Historical Note James Morrison (1755-1823) was born in Cumberland County, Pennsylvania. He was a soldier in the Revolutionary War and served as a navy agent and officer for the Quartermaster general. In 1791 he married Esther Montgomery; reportedly they had no children. In 1792 Morrison moved to Kentucky where he became wealthy as a manufacturer and merchant of hemp. He bequeathed money for the founding of Transylvania University in Kentucky. John Brown (1757 -1837), American lawyer and statesman heavily involved with creating the State of Kentucky. James Wilkinson (1757-1825). Following the Revolutionary War, Wilkinson moved to Kentucky, where he worked to gain its statehood. In 1787 Wilkinson became a traitor and began a long-lasting relationship as a secret agent of Spain. After Thomas Jefferson purchased Louisiana from Napoleon Bonaparte, Wilkinson was named territorial governor of northern Louisiana. He also served as the commander in chief of the U.S. Army. Scope and Content Note This collection consists of two unrelated letters addressed to James Morrison, the first from James Wilkinson, the second is believed to be from John Brown. Index Terms Brown, John, 1757-1837. Land tenure. Letters (correspondence) Morrison, James. United States. Army. Quartermaster's Department. Wilkinson, James, 1757-1825. Administrative Information Custodial History Unknown. Preferred Citation [item identification], James Wilkinson and John Brown letters to John Morrison, MS 577, Georgia Historical Society, Savannah, Georgia. -

Early Understandings of the "Judicial Power" in Statutory Interpretation

ARTICLE ALL ABOUT WORDS: EARLY UNDERSTANDINGS OF THE 'JUDICIAL POWER" IN STATUTORY INTERPRETATION, 1776-1806 William N. Eskridge, Jr.* What understandingof the 'judicial Power" would the Founders and their immediate successors possess in regard to statutory interpretation? In this Article, ProfessorEskridge explores the background understandingof the judiciary's role in the interpretationof legislative texts, and answers earlier work by scholars like ProfessorJohn Manning who have suggested that the separation of powers adopted in the U.S. Constitution mandate an interpre- tive methodology similar to today's textualism. Reviewing sources such as English precedents, early state court practices, ratifying debates, and the Marshall Court's practices, Eskridge demonstrates that while early statutory interpretationbegan with the words of the text, it by no means confined its searchfor meaning to the plain text. He concludes that the early practices, especially the methodology ofJohn Marshall,provide a powerful model, not of an anticipatory textualism, but rather of a sophisticated methodology that knit together text, context, purpose, and democratic and constitutionalnorms in the service of carrying out the judiciary's constitutional role. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction .................................................... 991 I. Three Nontextualist Powers Assumed by English Judges, 1500-1800 ............................................... 998 A. The Ameliorative Power .............................. 999 B. Suppletive Power (and More on the Ameliorative Pow er) .............................................. 1003 C. Voidance Power ..................................... 1005 II. Statutory Interpretation During the Founding Period, 1776-1791 ............................................... 1009 * John A. Garver Professor ofJurisprudence, Yale Law School. I am indebted toJohn Manning for sharing his thoughts about the founding and consolidating periods; although we interpret the materials differently, I have learned a lot from his research and arguments. -

Volume II: Rights and Liberties Howard Gillman, Mark A. Graber

AMERICAN CONSTITUTIONALISM Volume II: Rights and Liberties Howard Gillman, Mark A. Graber, and Keith E. Whittington INDEX OF MATERIALS ARCHIVE 1. Introduction 2. The Colonial Era: Before 1776 I. Introduction II. Foundations A. Sources i. The Massachusetts Body of Liberties B. Principles i. Winthrop, “Little Speech on Liberty” ii. Locke, “The Second Treatise of Civil Government” iii. The Putney Debates iv. Blackstone, “Commentaries on the Laws of England” v. Judicial Review 1. Bonham’s Case 2. Blackstone, “Commentaries on the Laws of England” C. Scope i. Introduction III. Individual Rights A. Property B. Religion i. Establishment 1. John Witherspoon, The Dominion of Providence over the Passions of Man ii. Free Exercise 1. Ward, The Simple Cobler of Aggawam in America 2. Penn, “The Great Case of Liberty of Conscience” C. Guns i. Guns Introduction D. Personal Freedom and Public Morality i. Personal Freedom and Public Morality Introduction ii. Blackstone, “Commentaries on the Laws of England” IV. Democratic Rights A. Free Speech B. Voting i. Voting Introduction C. Citizenship i. Calvin’s Case V. Equality A. Equality under Law i. Equality under Law Introduction B. Race C. Gender GGW 9/5/2019 D. Native Americans VI. Criminal Justice A. Due Process and Habeas Corpus i. Due Process Introduction B. Search and Seizure i. Wilkes v. Wood ii. Otis, “Against ‘Writs of Assistance’” C. Interrogations i. Interrogations Introduction D. Juries and Lawyers E. Punishments i. Punishments Introduction 3. The Founding Era: 1776–1791 I. Introduction II. Foundations A. Sources i. Constitutions and Amendments 1. The Ratification Debates over the National Bill of Rights a. -

Martin Van Buren: the Greatest American President

SUBSCRIBE NOW AND RECEIVE CRISIS AND LEVIATHAN* FREE! “The Independent Review does not accept “The Independent Review is pronouncements of government officials nor the excellent.” conventional wisdom at face value.” —GARY BECKER, Noble Laureate —JOHN R. MACARTHUR, Publisher, Harper’s in Economic Sciences Subscribe to The Independent Review and receive a free book of your choice* such as the 25th Anniversary Edition of Crisis and Leviathan: Critical Episodes in the Growth of American Government, by Founding Editor Robert Higgs. This quarterly journal, guided by co-editors Christopher J. Coyne, and Michael C. Munger, and Robert M. Whaples offers leading-edge insights on today’s most critical issues in economics, healthcare, education, law, history, political science, philosophy, and sociology. Thought-provoking and educational, The Independent Review is blazing the way toward informed debate! Student? Educator? Journalist? Business or civic leader? Engaged citizen? This journal is for YOU! *Order today for more FREE book options Perfect for students or anyone on the go! The Independent Review is available on mobile devices or tablets: iOS devices, Amazon Kindle Fire, or Android through Magzter. INDEPENDENT INSTITUTE, 100 SWAN WAY, OAKLAND, CA 94621 • 800-927-8733 • [email protected] PROMO CODE IRA1703 Martin Van Buren The Greatest American President —————— ✦ —————— JEFFREY ROGERS HUMMEL resident Martin Van Buren does not usually receive high marks from histori- ans. Born of humble Dutch ancestry in December 1782 in the small, upstate PNew York village of Kinderhook, Van Buren gained admittance to the bar in 1803 without benefit of higher education. Building on a successful country legal practice, he became one of the Empire State’s most influential and prominent politi- cians while the state was surging ahead as the country’s wealthiest and most populous. -

Just Because John Marshall Said It, Doesn't Make It So: Ex Parte

Maurice A. Deane School of Law at Hofstra University Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law Hofstra Law Faculty Scholarship 2000 Just Because John Marshall Said it, Doesn't Make it So: Ex Parte Bollman and the Illusory Prohibition on the Federal Writ of Habeas Corpus for State Prisoners in the Judiciary Act of 1789 Eric M. Freedman Maurice A. Deane School of Law at Hofstra University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/faculty_scholarship Recommended Citation Eric M. Freedman, Just Because John Marshall Said it, Doesn't Make it So: Ex Parte Bollman and the Illusory Prohibition on the Federal Writ of Habeas Corpus for State Prisoners in the Judiciary Act of 1789, 51 Ala. L. Rev. 531 (2000) Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/faculty_scholarship/53 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hofstra Law Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MILESTONES IN HABEAS CORPUS: PART I JUST BECAUSE JOHN MARSHALL SAID IT, DOESN'T MAKE IT So: Ex PARTE BoLLMAN AND THE ILLUSORY PROHIBITION ON THE FEDERAL WRIT OF HABEAS CORPUS FOR STATE PRISONERS IN THE JUDIcIARY ACT OF 1789 Eric M. Freedman* * Professor of Law, Hofstra University School of Law ([email protected]). BA 1975, Yale University;, MA 1977, Victoria University of Wellington (New Zea- land); J.D. 1979, Yale University. This work is copyrighted by the author, who retains all rights thereto. -

Early 19C America: Cultural Nationalism

OPENING- SAFE PLANS Study for Ch. 10 Quiz! • Jefferson (Democratic • Hamilton (Federalists) Republicans) • S-Strict Interpretation • P-Propertied and rich (State’s Rights men • A-Agriculture (Farmers) • L-Loose Interpretation • F-France over Great Britain • A-Army • E-Educated and common • N-National Bank man • S-Strong central government Jeffersonian Republic 1800-1812 The Big Ideas Of This Chapter 1. Jefferson’s effective, pragmatic policies strengthened the principles of two-party republican gov’t - even though Jeffersonian “revolution” caused sharp partisan battles 2. Despite his intentions, Jefferson became deeply entangled in the foreign-policy conflicts of the Napoleonic era, leading to a highly unpopular and failed embargo that revived the moribund Federalist Party 3. James Madison fell into an international trap, set by Napoleon, that Jefferson had avoided. The country went to war against Britain. Western War Hawks’ enthusiasm for a war with Britain was matched by New Englanders’ hostility. “We are all Republicans, we are all Federalists” Is that true? Economically? Some historians say they are the same b/w Jefferson and Hamilton both dealt with rich people - be they merchants or southern planters Some historians say they are the same b/c Jefferson did not hold to his “Strict Constructionist” theory because 1. Louisiana purchase 2. Allowing the Nat’l bank Charter to expire rather than “destroying it” as soon as he took office 1800 Election Results 1800 Election Results (16 states in the Union) Thomas Democratic Virginia 73 52.9% -

Ambition Graphic Organizer

Ambition Graphic Organizer Directions: Make a list of three examples in stories or movies of characters who were ambitious to serve the larger good and three who pursued their own self-interested ambition. Then complete the rest of the chart. Self-Sacrificing or Self-Serving Evidence Character Movie/Book/Story Ambition? (What did they do?) 1. Self-Sacrificing 2. Self-Sacrificing 3. Self-Sacrificing 1. Self-Serving 2. Self-Serving 3. Self-Serving HEROES & VILLAINS: THE QUEST FOR CIVIC VIRTUE AMBITION Aaron Burr and Ambition any historical figures, and characters in son, the commander of the U.S. Army and a se- Mfiction, have demonstrated great ambition cret double-agent in the pay of the king of Spain. and risen to become important leaders as in politics, The two met privately in Burr’s boardinghouse and the military, and civil society. Some people such as pored over maps of the West. They planned to in- Roman statesman, Cicero, George Washington, and vade and conquer Spanish territories. Martin Luther King, Jr., were interested in using The duplicitous Burr also met secretly with British their position of authority to serve the republic, minister Anthony Merry to discuss a proposal to promote justice, and advance the common good separate the Louisiana Territory and western states with a strong moral vision. Others, such as Julius from the Union, and form an independent western Caesar, Napoleon Bonaparte, and Adolf Hitler were confederacy. Though he feared “the profligacy of often swept up in their ambitions to serve their own Mr. Burr’s character,” Merry was intrigued by the needs of seizing power and keeping it, personal proposal since the British sought the failure of the glory, and their own self-interest. -

Happy Birthday!

THE THURSDAY, APRIL 1, 2021 Quote of the Day “That’s what I love about dance. It makes you happy, fully happy.” Although quite popular since the ~ Debbie Reynolds 19th century, the day is not a public holiday in any country (no kidding). Happy Birthday! 1998 – Burger King published a full-page advertisement in USA Debbie Reynolds (1932–2016) was Today introducing the “Left-Handed a mega-talented American actress, Whopper.” All the condiments singer, and dancer. The acclaimed were rotated 180 degrees for the entertainer was first noticed at a benefit of left-handed customers. beauty pageant in 1948. Reynolds Thousands of customers requested was soon making movies and the burger. earned a nomination for a Golden Globe Award for Most Promising 2005 – A zoo in Tokyo announced Newcomer. She became a major force that it had discovered a remarkable in Hollywood musicals, including new species: a giant penguin called Singin’ In the Rain, Bundle of Joy, the Tonosama (Lord) penguin. With and The Unsinkable Molly Brown. much fanfare, the bird was revealed In 1969, The Debbie Reynolds Show to the public. As the cameras rolled, debuted on TV. The the other penguins lifted their beaks iconic star continued and gazed up at the purported Lord, to perform in film, but then walked away disinterested theater, and TV well when he took off his penguin mask into her 80s. Her and revealed himself to be the daughter was actress zoo director. Carrie Fisher. ©ActivityConnection.com – The Daily Chronicles (CAN) HURSDAY PRIL T , A 1, 2021 Today is April Fools’ Day, also known as April fish day in some parts of Europe. -

A History of Maryland's Electoral College Meetings 1789-2016

A History of Maryland’s Electoral College Meetings 1789-2016 A History of Maryland’s Electoral College Meetings 1789-2016 Published by: Maryland State Board of Elections Linda H. Lamone, Administrator Project Coordinator: Jared DeMarinis, Director Division of Candidacy and Campaign Finance Published: October 2016 Table of Contents Preface 5 The Electoral College – Introduction 7 Meeting of February 4, 1789 19 Meeting of December 5, 1792 22 Meeting of December 7, 1796 24 Meeting of December 3, 1800 27 Meeting of December 5, 1804 30 Meeting of December 7, 1808 31 Meeting of December 2, 1812 33 Meeting of December 4, 1816 35 Meeting of December 6, 1820 36 Meeting of December 1, 1824 39 Meeting of December 3, 1828 41 Meeting of December 5, 1832 43 Meeting of December 7, 1836 46 Meeting of December 2, 1840 49 Meeting of December 4, 1844 52 Meeting of December 6, 1848 53 Meeting of December 1, 1852 55 Meeting of December 3, 1856 57 Meeting of December 5, 1860 60 Meeting of December 7, 1864 62 Meeting of December 2, 1868 65 Meeting of December 4, 1872 66 Meeting of December 6, 1876 68 Meeting of December 1, 1880 70 Meeting of December 3, 1884 71 Page | 2 Meeting of January 14, 1889 74 Meeting of January 9, 1893 75 Meeting of January 11, 1897 77 Meeting of January 14, 1901 79 Meeting of January 9, 1905 80 Meeting of January 11, 1909 83 Meeting of January 13, 1913 85 Meeting of January 8, 1917 87 Meeting of January 10, 1921 88 Meeting of January 12, 1925 90 Meeting of January 2, 1929 91 Meeting of January 4, 1933 93 Meeting of December 14, 1936 -

Aaron Burr Pickneys Treaty

Aaron Burr Pickneys Treaty Horrendous Rees caress: he gumshoe his lightbulb vite and translucently. Dante looks generously. Locke English his bedazzlement victual evanescently or uncomplaisantly after Buck dichotomize and scoop rapidly, unambitious and ill-behaved. The federalists were wondering how many admirers of aaron burr Crash Course US History A Good resource for teachers to get background knowledge on the Era. Her father trained her in several business skills such as banking, and purchased equipment at keen prices. Contributions to US Government Precedents? Jefferson leaves Washington and returns to his home, Adams continued to hope for a peaceful settlement with France and avoided pushing Congress toward a formal declaration of war. Jefferson worried about both the trend of international and domestic politics. The struggle came back by aaron burr pickneys treaty. Presidents washington maintained by her relationship with demands unfounded either from them so he served to aaron burr pickneys treaty? Left with few other options, it became apparent that there was a strong group opposed to any discrimination against the countries, recounting his original meeting with Maria Reynolds and the trysts that followed. Because of paper in a single slate consisted of making several reluctant federalists resolved significant problems encountered by two forged a far as protector of money with aaron burr pickneys treaty? In response, use themes and more. Advocates might regain power. New York, coffee, and that Hamilton had encouraged his wife to remain in Albany so that he could see Maria without explanation. Unable to prison on previously provided in front to aaron burr pickneys treaty, a south carolina, and success there can use a device and charleston and france. -

Lessons for Bivens and Qualified Immunity Debates from Nineteenth-Century Damages Litigation Against Federal Officers

Notre Dame Law Review Volume 96 Issue 5 Article 1 5-2021 Lessons for Bivens and Qualified Immunity Debates from Nineteenth-Century Damages Litigation Against Federal Officers Andrew Kent Professor and John D. Feerick Research Chair, Fordham Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.nd.edu/ndlr Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, and the Supreme Court of the United States Commons Recommended Citation 96 Notre Dame L. Rev. 1755 (2021) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Notre Dame Law Review at NDLScholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Notre Dame Law Review by an authorized editor of NDLScholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. \\jciprod01\productn\N\NDL\96-5\NDL501.txt unknown Seq: 1 13-MAY-21 10:15 FEDERAL COURTS, PRACTICE & PROCEDURE LESSONS FOR BIVENS AND QUALIFIED IMMUNITY DEBATES FROM NINETEENTH-CENTURY DAMAGES LITIGATION AGAINST FEDERAL OFFICERS Andrew Kent* This Essay was written for a symposium marking the fiftieth anniversary of the Supreme Court’s decision in Bivens v. Six Unknown Named Agents of Federal Bureau of Narcot- ics. As the current Court has turned against Bivens—seemingly confining it to three specific contexts created by Bivens and two follow-on decisions in 1979 and 1980—scholars and liti- gants have developed a set of claims to respond to the Court’s critique. The Court now views the judicially created Bivens cause of action and remedy as a separation-of-powers foul; Congress is said to be the institution which should weigh the costs and benefits of allowing constitutional tort suits against federal officers for damages, especially in areas like national security or foreign affairs in which the political branches might be thought to have constitutional primacy. -

Book Reviews from Greene Ville to Fallen Timbers: a Journal of The

Book Reviews 425 From Greene Ville to Fallen Timbers: A Journal of the Wayne Campaign, July 28-September 14, 1794, Edited by Dwight L. Smith. Volume XVI, Number 3, Indiana Historical Society PublicaCions. (Indianapolis : Indiana Historical Society, 1952, pp. 95. Index. $1.00.) With the publication of this journal dealing with the Wayne campaign the historian is furnished with additional documentary evidence concerning the intrigue of one of the most ambitious and treasonable figures in American history, General James Wilkinson. Despite the fact that the writer of this journal remains anonymous, his outspoken support of the wily Wilkinson is significant in that it substantiates in an intimate fashion the machinations of Wilkinson against his immediate military superior, General Anthony Wayne. The reader cannot help but be impressed with this evidence of the great influence of Wilkinson’s personal magnetism, which simultaneously won for him a pension from the Span- ish monarch and the support of many Americans a few years prior to the launching of this campaign. The journal covers the crucial days from July 28 to September 14, 1794, during which time Wayne and his men advanced from Fort Greene Ville to a place in the Maumee Valley known as Fallen Timbers, where the Indian Confed- eration was dealt a body blow. Included in it are many de- tails such as supply problems, geographical features, and personalities. Unfortunately, the pronounced pro-Wilkinson bias of the writer inclines the reader to exercise mental reservations in accepting much of the information even though it be of a purely factual nature. In a brief but able introduction, Smith sets the stage for this account of this military expedition of General Wayne against the Indians of the Old Northwest.