Carolingian Art

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cultural-History-Fin.Ai

CHRONOLOGICAL CHART OF WORLD CULTURAL HISTORY 600000 100000 10000 3000 2500 2000 1500 1000 500 B.C. 1 1 A.D. 100 200 300 400 500 600 700 800 900 1000 1100 1200 1300 1400 1500 1600 1700 1800 1900 2000 38 45 10 94 92 36 92 68 03 68 46 70 c. 2000 1125 +- 130 c. 1000 870 +- 130 ASUKA PERIOD HAKUHO PERIOD NARA PERIOD HEIAN PERIOD KAMAKURA PERIOD MUROMACHI PERIOD AZUCHI EDO PERIOD MODERN AGE 7290 + 500 c. 10000 - 5600 +- 325 3150 +- 400 2115 +- 135 Tumulus culture 49 57 65 Konin Jogan cul. Fujiwara cul. Nagashima MOMOYAMA P. Jomon Culture Yayoi culture Hakuho cul. Nara cul. Nakayama cul. JAPAN 1 Pre-pottery Culture 93 62 72 87 97 08 17 29 82 10 34 59 77 85 01 38 47 68 90 12 24 37 53 65 08 35 56 77 84 01 19 49 64 78 83 cul. Kamigata cul. Edo cul. JAPAN 1 24 34 45 75 94 44 67 04 32 73 92 15 24 55 61 88 04 16 51 64 81 89 04 18 30 54 12 26 89 Middle stage Late stage Asuka cul. ASIAN CULTURAL SPHERE CULTURAL ASIAN 1st stage 2nd st. Early st. Early Stage Middle stage Late stage 4th stage 5th stage 6th stage I II SPHERE CULTURAL ASIAN PYONHAN c. 69 IMNA 62 76 35 59 56 92 36 97 10 45 48 c. 194 c. 108 CHINHAN c. 56 SILLA R L I REPUBLIC of KOREA Eastern Asia Eastern UNIFIED SILLA ( ) KIJA 75 c. 46 PAEKCHE 63 TAE KOREA 2 MAHAN R( L) ISSI CHOSON DYNASTY JAPANESE 2 CHOSON LOLANG 13 Tumulus culture in three Kingdoms 68 18 KORYO MONGOL’S HAN (POSSESSION) c. -

Byzantium and France: the Twelfth Century Renaissance and the Birth of the Medieval Romance

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 12-1992 Byzantium and France: the Twelfth Century Renaissance and the Birth of the Medieval Romance Leon Stratikis University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the Modern Languages Commons Recommended Citation Stratikis, Leon, "Byzantium and France: the Twelfth Century Renaissance and the Birth of the Medieval Romance. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 1992. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/2521 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Leon Stratikis entitled "Byzantium and France: the Twelfth Century Renaissance and the Birth of the Medieval Romance." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Modern Foreign Languages. Paul Barrette, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: James E. Shelton, Patrick Brady, Bryant Creel, Thomas Heffernan Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation by Leon Stratikis entitled Byzantium and France: the Twelfth Century Renaissance and the Birth of the Medieval Romance. -

“Forms Assembled in the Light” Week One: Early Medieval Art

ART HISTORY Journey Through a Thousand Years “Forms Assembled in the Light” Week One: Early Medieval Art The Craftsmen Who Saved Civilisation - The Civilisation that Survived – Controversy Over Images – Decoding Anglo-Saxon Art - Basilicas - Illuminated Manuscripts – In Search of Three Dimensions – From the Vaults: The Lindau Gospels – Ottonian Art – The Bernward Doors - An Introduction to the Bestiary, Book of Beasts in the Medieval World - The painted crypt of San Isidoro at León, Spain By Megginede - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=45924271 “Great nations write their autobiographies in three manuscripts[;] the book of their deeds, the book of their words, and the book of their art. Not one of these works can be understood unless we read the two others, but of the three the only trustworthy one is the last.” – Ruskin Kenneth Clark: “The Craftsmen Who Saved Civilization” From Civilisation: A Personal View (1969) People sometimes tell me they prefer barbarism to civilization. I doubt if they have given it a long enough trial. Like the people of Alexandria they are bored by civilisation; but all the evidence suggests that the boredom of barbarism is infinitely greater. Quite apart from discomforts and privations, there was no escape from it. Very restricted company, no books, no light after dark, no hope. On one side of the sea battering away, on the other the infinite stretches of the bog and the forest. A most melancholy existence, and the Anglo- Saxon poets had no illusions about it: A wise man may grasp how ghastly it shall be When all this world’s wealth standeth waste Even as now, in many places over the earth, Walls stand windbeaten, Heavy with hoar frost; ruined habitations… The maker of men has so marred this dwelling That human laughter is not heard about it, And idle stand these old giant works. -

Early Medieval Art After the Collap

AP ART HISTORY STUDY SHEET Name: Date: Period: Gardener’s Notes Unit 10 - Chapter 16: Early Medieval Art After the collapse of the Roman Empire, Western Europe entered what is known as the Dark Ages. Power became decentralized, dispersed among various nomadic tribes. Trade among towns and outposts collapsed because the Roman legions were no longer present to maintain order. When comparing the art produced during early medieval times with the many achievements of the Roman Empire, it is obvious why historians first labeled the period the Dark Ages. However, recent discoveries and scholarship have uncovered works of art and architecture that reveal the presence of rich cultures between the years 500 and 1000 CE. For the AP Art History exam, the early Middle Ages includes four stages: (1) Art of the Warrior Lords, (2) Hiberno-Saxon Art, (2) Carolingian Art, and (4) Ottonian Art. The 2004 exam contained a slide-based short essay comparing a picture of a purse cover from Sutton Hoo, a site during the Warrior Lord Period, to ta carpet page from the Lindisfarne Gospels , a Hiberno-Saxon illuminated manuscript. Past tests also required students to discuss the characteristics of Carolingian illuminated manuscript. Multiple-choice questions have tested student’s recognition of a famous Ottonian church and its bronze doors. Early Medieval art is groups with Early Christian and Byzantine Art as 5 percent to 10 percent of the points on the AP Art History exam, which is a small percentage of the total points. Nonetheless, this chapter provides you with the necessary knowledge about the early Medieval period to prepare you for possible test questions. -

LAWRENCE NEES CURRICULUM VITAE (Updated August 2017)

1 LAWRENCE NEES CURRICULUM VITAE (updated August 2017) Personal Department of Art History, University of Delaware, Newark DE 19716 U.S.A. 220 S. Ridley Creek Rd., Moylan, Pennsylvania 19065 U.S.A. telephone: office (302) 831-8415 fax: office (302) 831-8105 email: [email protected] born Chicago, Illinois, August 9, 1949 (U.S.A. citizen) Education University of Chicago, 1966-1970, B.A. with Honors, 1970. Harvard University, Department of Fine Arts, 1970-1971 and 1973-1977, M.A. 1974, Ph.D. 1977. Dissertation, 1976: "The Illustrations of the Gundohinus Gospels at Autun" (adviser: Ernst Kitzinger). Professional Positions University of Victoria (Canada), Department of History in Art, Visiting Sessional Lecturer, 1976-1977. University of Massachusetts at Boston, Department of Art, Lecturer, 1977-1978. Harvard University, Department of Fine Arts, Visiting Assistant Professor, Summer 1980. Bryn Mawr College, Visiting Professor, 1989, 2000. Temple University, Visiting Professor, 1998, 2004, 2005. University of Delaware, Department of Art Conservation, Adjunct Professor, 1996-1999. University of Delaware, Department of Art History Assistant Professor, 1978-1982 Associate Professor, 1982-1988 Professor, 1988 - present. (Associate Chair, 1986-1987, 2001-2002; Director of Graduate Studies 2002-2004; Interim Chair, 2013-2014; Chair 2015-2019). H. Fletcher Brown Chair of Humanities, 2016 - present. Professional Associations Medieval Academy of America (Fellow, elected 2014) International Center of Medieval Art Society of Antiquaries of London (Fellow, elected 2005) College Art Association of America Medieval Academy of Ireland Byzantine Studies Association of North America Historians of Islamic Art Association Italian Art Society American Society for Irish Medieval Studies Vergilian Society Delaware Valley Medieval Association 2 LAWRENCE NEES CURRICULUM VITAE Publications (Books) From Justinian to Charlemagne. -

LOCALIZING BYZANTIUM: GROUP II ENAMELS on the RELIQUARY of SAINT BLAISE in DUBROVNIK Ana Munk

LOCALIZING BYZANTIUM: GROUP II ENAMELS ON THE RELIQUARY OF SAINT BLAISE IN DUBROVNIK Ana Munk A. Munk University of Zagreb Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Department of History of Art Ivana Lučića 3, HR-10000 Zagreb [email protected] The article analyzes four enamel roundels on the reliquary of Saint Blaise in Dubrovnik Cathedral trea- sury. It has not been noticed previously that these enamels contain features which makes it unlikely that they were made in Constantinople. The lack of inscriptions which is more characteristic for Byzantinizing enamel work made in Italy, and the depiction of the two martyrs which does not reflect the codes set for Byzantine saints’ attire indicate the artist’s Italo-Byzantine training and, possibly, a local identity of the two martyrs. Stylistically, plain design of these enamels indicate a run of the mill manufacture that has not utilized all iconographical, coloristic and decorative options that an 11th or 12th century enamel workshop in Constantinople may have had at its disposal. Key words: Saint Blaise reliquary, cloisonné enamel, Dubrovnik, Byzantine saints, Italo-Byzantine style, saints’ attire This contribution to studies in honor of professor Igor Fisković takes as its subject four enamel plaques on the reliquary of Saint Blaise, an artwork that testifies to Dubrovnik's earliest art and history, to which professor Fisković dedicated many years of his academic career (Fig. 1). The head relic of Saint Blaise was found in 1026, but the early history of the reliquary is unknown. The first mention dates to 1335 when the entry in the earliest inventory of Dubrovnik cathedral reads: “caput Beati Blasij epi. -

THE SIGNIFICANCE of DOT-PATTERNS in CAROLINGIAN MANUSCRIPTS by INGA MORRIS B.A., University of British Columbia, 1964 a THESIS S

THE SIGNIFICANCE OF DOT-PATTERNS IN CAROLINGIAN MANUSCRIPTS by INGA MORRIS B.A., University of British Columbia, 1964 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of Fine Arts We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA April, 1965 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia,, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that per• mission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publi• cation of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission* Pine Arts Department of ; The University of British Columbia, Vancouver 8, Canada April 17, 1965. Date ABSTRACT The significance of dot patterns in Carolingian manuscripts is the subject of my research. In my investigation into the sources of these pat• terns I hope to show some relationship between them and metal working techniques to which could be attributed an overall development of pattern and design during the early Middle Ages. Since the art of the period reflects so strongly the social and political conditions existent during the reign of Charlemagne I have also included a brief summary of those relevant historical conditions. The adverse situation prevailing in the Frankish kingdom during the seventh century together with the weak• ness of its rulers enabled the Carolingian family to ob• tain power, and when Charlemagne became the sole ruler in 771 he continued to carry out the family policy of uniting the peoples of the West and initiated a revival of Roman culture and learning in his kingdom. -

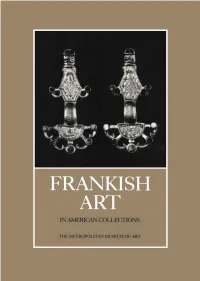

Frankish Art in American Collections

FRANKISH ART IN AMERICAN COLLECTIONS FRANKISH ART IN AMERICAN COLLECfiONS KATHARINE REYNOLDS BROWN THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART The author wishes to thank William D. Wixom and Barbara Drake Boehm of the Department of Medieval Art for their support of this project. On the cover: Fig. 12. Pair of bow fibulae. France. 6th century. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Gift of j. Pierpont Morgan, 1917 (17.191.172,173) Frontispiece: Fig. 16. Openwork plaque. Wanquetan. Second half of 7th century. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Gift of j. Pierpont Morgan, 1917 (17 .192.163) he wealth of Frankish objects in American collections provides a comprehensive picture of the character of Frankish art from its T inception in the Late Roman era through its metamorphosis into Carolingian art. The Frankish holdings of The Metropolitan Museum of Art-in particular the magnificent J. Pierpont Morgan collection-are in themselves sufficient to demonstrate all the elements necessary for an understanding of Frankish art and how it led to Carolingian and later medieval art. The Walters Art Gallery in Baltimore also has a fine collec tion of Frankish art. Smaller American collections, too, each play a role in defining the complex nature of Frankish art. This publication will provide the first survey ever of American museum holdings in Frankish art. FRANKISH ART: THE PATH 'TO CAROLINGIAN ART he Franks-one of the Barbarian Germanic peoples of the great migratory period of the fifth to seventh centuries A.D. -provided T the essential link between Late Roman art and the Carolingian art that laid the groundwork for the splendid metalwork of the medieval period. -

The History of Art Department, TCD the Dissertation Database 1976 1 Merry M.S. 18Th Century, 19Th Century Painting. Italy, Rome

The History of Art Department, TCD The Dissertation Database YEAR 1976 NUMBER 1 SURNAME Merry NAME M.S. TITLE Vincenzo Camuccini (1771 - 1844) . Roman Painter. PERIOD 18th century, 19th century ARCH_PAINT_SCULPT... Painting. COUNTRY_IES_ OF INTEREST Italy, Rome. MISCELLANEOUS This dissertation provides biographical notes, a short survey of artistic training and influences, a catalogue of paintings with an introduction, a note on the Camuccini’s Collection, and discusses the artist’s relationship with patrons and other artists. YEAR *1976 NUMBER 2 SURNAME Warner NAME Gloria Gaghan TITLE Saint Patrick’s Cathedral, Dublin. A building history. PERIOD 12th century,13th century,14th century,15th ARCH_PAINT_SCULPT... Architecture. COUNTRY_IES_ OF INTEREST Ireland, Dublin. MISCELLANEOUS This paper gives a detailed architectural history and analysis of St. Patrick’s Cathedral, Dublin. The History of Art Department, TCD The Dissertation Database YEAR *1977 NUMBER 1 SURNAME Barry NAME Siuban TITLE Merrion Square : A documentary and architectural study. PERIOD 18th century, 19th century ARCH_PAINT_SCULPT... Architecture. COUNTRY_IES_ OF INTEREST Ireland, Dublin. MISCELLANEOUS This dissertation is divided into two parts. Part one deals with the growth and development of Merrion Square from its beginnings in the early 1750’s to the mid 1820’s, by which time the development of the area was almost completed. Part two considers the buildings in the square, principally their facades and plan types and how these relate to each other. Interior decoration has not been dealt with as it would have increased the scope of the work to an unmanageable size. YEAR *1977 NUMBER 2 SURNAME Chevenix Trench NAME Lucy TITLE A catalogue of the paintings and architectural drawings in the possession of Major E.A. -

Art of the Middle Ages 1St Edition Ebook

ART OF THE MIDDLE AGES 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Janetta Rebold Benton | 9780500203507 | | | | | Art of the Middle Ages 1st edition PDF Book Secular buildings also often had wall-paintings, although royalty preferred the much more expensive tapestries, which were carried along as they travelled between their many palaces and castles, or taken with them on military campaigns—the finest collection of late-medieval textile art comes from the Swiss booty at the Battle of Nancy , when they defeated and killed Charles the Bold , Duke of Burgundy , and captured all his baggage train. The paradox is that the cultural means that are being employed — video art, installation, large color photographs and so forth — seem genuinely international. During the period typology became the dominant approach in theological literature and art to interpreting the bible, with Old Testament incidents seen as pre-figurations of aspects of the life of Christ, and shown paired with their corresponding New Testament episode. A pioneering role in this respect was played by London as a consequence of the limited power of the monarch, which meant that the court dominated culture much less than it did in France at the same time. Indeed, the history of medieval art can be seen as the history of the interplay between the elements of classical , early Christian and "barbarian" art. The pattern of artistic employment in the medieval period and the Renaissance varied. Given the example of Leonardo da Vinci, this appears to make sense. Anglo-Saxon silver sceat , Kent , c. Until about the 11th century most of Europe was short of agricultural labour, with large amounts of unused land, and the Medieval Warm Period benefited agriculture until about We have a dedicated site for Germany. -

Vida Joyce Hull

Vida Joyce Hull Department of Art and Design 1315 Plantation Drive Box 70708, Ball Hall, 232 Johnson City, Tennessee 37604 Sherrod Drive East Tennessee State University Home telephone: 423-928-7980 Johnson City, Tennessee 37614 Mobile phone: 423-737-2189 [email protected] Office telephone: 423-439-5608 Department fax: 423-439-4393 Education Ph.D. Bryn Mawr College, History of Art, 1979 Dissertation: "Hans Memlinc's Paintings for the Hospital of St. John in Bruges" (adviser: James Snyder) Doctoral examination topics: Carolingian Art (Medieval), Early Netherlandish Painting (Renaissance), Bernini (Baroque), Cézanne (Modern) M.A. Ohio State University, History of Art, 1970 Thesis: "Piero di Cosimo's Allegory in the National Gallery, Washington: An Iconographic Study" (adviser: Maurice Cope) Major areas: Italian Renaissance, Medieval, and Baroque art Minor: Philosophy B.A. Rollins College, Art History major, 1968 (High Distinction) Honors thesis: "Christian Art of the Twentieth Century: A Continuing Tradition" Art History major, fulfilled Studio Art major requirements Undergraduate honors: 1968 Tiedtke Award (annual art award), Honors at Entrance, Honors at Graduation (High Distinction), Phi Society, Rollins Scholars, Dean's & President's Lists Infrared Reflectography Workshop at the Harvard University Museums of Art, August 17-22, 1998 Other courses: Courses at East Tennessee State University over the years (1986-2007): Latin I (audit, summer), The Protestant Reformation (audit, fall 2000), Raku workshop (summer 1990), Computer as a Tool (summer1987); various faculty workshops on exam writing, preparing writing intensive and oral intensive courses, helping students build critical thinking skills, & training sessions on Microsoft Word, Excel, Photoshop, Blackboard, D2L, digital media, etc. -

KEY CONCEPTS for the EARLY MEDIEVAL PERIOD

KEY CONCEPTS for the EARLY MEDIEVAL PERIOD DEVELOPMENT OF BOOKS The transition from the scroll to the bound book in this period was critical in the preservation and transmission of learning in Europe. Illuminated manuscripts are among the most important art objects created during the Early Middle Ages. Students should understand the process of bookmaking, copying, and illustrating that was developed during this period. CHARLEMAGNE'S PROJECT Charlemagne's attempt to revive the arts and create a culture along the lines of ancient Rome is the historical background for the most important period of art in the Early Middle Ages. His accomplishments and their influence, especially Carolingian miniscule and monastery design, are key concepts that students should take from this chapter. INTERLACE Ribbon interlace and animal interlace were used as decoration on a variety of art objects from Sweden, Norway, and the British Isles. Students should be able to connect the themes of animal interlace to the presumed religious beliefs of the people that developed it. EARLY MEDIEVAL ART Three Basic parts to Early Medieval Era: Fall of Western Empire 400-600 Art of the Warlords: The PAGAN Years Western Empire now broken up amongst the Goths, Angles, Saxons and Franks… Known for the ‘animal style’ that is prevalent in this period… Chi Rho Iota from the Book of Kells 700-800 HIBERNO-SAXON ART: Produced in Ireland (Hiberno) and England (Saxon). Much like the Pagan art (interwoven designs), but contained Christian concepts. CAROLINGIAN Period (768-814): Charlemagne crowned King of the Franks and Christian Ruler in 768… Cathedral of Aachen promoted the ‘three-part elevation’ to Churches… Education to the people through art and illuminated manuscripts, like the Ebbo Gospels OTTONIAN Periods (950-1050): The Three German Ottos known for uniting the region under a common Christian Rule again, which sparks the need for bigger churches in the ROMANESQUE period.