Australia's Democracy Pp 128-140

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RF177.Pdf (Redflag.Org.Au)

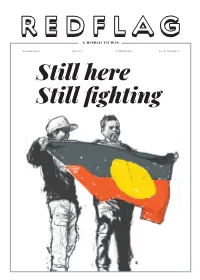

A WORLD TO WIN REDFLAG.ORG.AU ISSUE #177 19 JANUARY 2021 $3 / $5 (SOLIDARITY) Still here Still fi ghting REDFLAG | 19 JANUARY 2021 PUBLICATION OF SOCIALIST ALTERNATIVE REDFLAG.ORG.AU 2 Red Flag Issue # 177 19 January 2021 ISSN: 2202-2228 Published by Red Flag Support the Press Inc. Trades Hall 54 Victoria St Carlton South Vic 3053 [email protected] Christmas Island (03) 9650 3541 Editorial committee Ben Hillier Louise O’Shea Daniel Taylor Corey Oakley rioters James Plested Simone White fail nonetheless. Some are forced to complete rehabil- Visual editor itation programs and told that when they do so their James Plested appeals will be strengthened. They do it. They fail. These are men with families in Australia. They Production are workers who were raising children. They are men Tess Lee Ack n the first week of 2021, detainees at the Christ- who were sending money to impoverished family Allen Myers mas Island Immigration Detention Centre be- members in other countries. Now, with their visas can- Oscar Sterner gan setting it alight. A peaceful protest, which celled, they have no incomes at all. This has rendered Subscriptions started on the afternoon of 5 January, had by partners and children homeless. and publicity evening escalated into a riot over the treatment Before their transportation from immigration fa- Jess Lenehan Iof hundreds of men there by Home Affairs Minister cilities and prisons on the Australian mainland, some Peter Dutton and his Australian Border Force. Four of these men could receive visits from loved ones. Now What is days later, facing down reinforced numbers of masked, they can barely, if at all, get internet access to speak to armed Serco security thugs and Australian Federal them. -

Final Draft Questions.Indd

2011 Question Booklet 50 Questions time allowed – 45 minutes Your teacher will explain how to fi ll in school and personal details on the answer sheet before starting. Instructions • You will be given this Question Booklet, a Source Sheet and an Answer Sheet. • Some of the questions will ask you to refer to sources on the Source Sheet. • Answer all questions on the Answer Sheet by selecting the best answer from the alternatives given. • Indicate your answer by putting a cross in the box for the alternative you have chosen. • Think carefully about your answer before making a choice, but if you wish to change an answer shade the box with the incorrect answer completely and then place a cross in the box for the new answer. • Before starting, your teacher will explain how to fi ll in your school and personal details on the Answer Sheet – it is important to do this accurately so that names will be spelt correctly on certifi cates. The 2011 Australian History Competition is created and run by the History Teachers’ Association of Australia and The Giant Classroom. It is sponsored by Circle – The Centre for Innovation, Research, Creativity and Leadership in Education and Cambridge University Press. www.australianhistorycompetition.com.au Questions 1-3 refer to Source A 1. Who is the person shown in Source A? A Queen Victoria B Queen Elizabeth II C Dame Enid Lyons D Elizabeth Macarthur 2. Why is she represented on the banknote? A To satisfy the demands of feminist historians B She was a signifi cant fi gure in Australia’s history C She was Australia’s Head of State when the banknote was in use D To highlight Australia’s position as a Dominion of the British Empire 3. -

Red Flag Issue8 0.Pdf

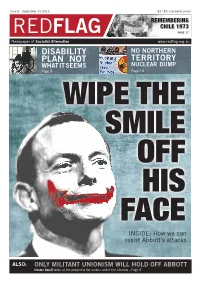

Issue 8 - September 10 2013 $3 / $5 (solidarity price) REMEMBERING FLAG CHILE 1973 RED PAGE 17 Newspaper of Socialist Alternative www.redfl ag.org.au DISABILITY NO NORTHERN PLAN NOT TERRITORY WHAT IT SEEMS NUCLEAR DUMP Page 8 Page 13 WIPE THE SMILE OFF HIS FACE INSIDE: How we can resist Abbott’s attacks ALSO: ONLY MILITANT UNIONISM WILL HOLD OFF ABBOTT Jerome Small looks at the prospects for unions under the Liberals - Page 9 2 10 SEPTEMBER 2013 Newspaper of Socialist Alternative FLAG www.redfl ag.org.au RED CONTENTS EDITORIAL 3 How Labor let the bastards in Mick Armstrong analyses the election result. 4 Wipe the smile off Abbott’s face ALP wouldn’t stop Abbo , Diane Fieldes on what we need to do to fi ght back. now it’s up to the rest of us 5 The limits of the Greens’ leftism A lot of people woke up on Sunday leader (any leader) and wait for the 6 Where does real change come from? a er the election with a sore head. next election. Don’t reassess any And not just from drowning their policies, don’t look seriously about the Colleen Bolger makes the argument for getting organised. sorrows too determinedly the night deep crisis of Laborism that, having David confront a Goliath in yellow overalls before. The thought of Tony Abbo as developed for the last 30 years, is now prime minister is enough to make the at its most acute point. Jeremy Gibson reports on a community battling to keep McDonald’s soberest person’s head hurt. -

Australia in the League of Nations: a Centenary View

RESEARCH PAPER SERIES, 2018–19 21 DECEMBER 2018 Australia in the League of Nations: a centenary view James Cotton Emeritus Professor of Politics, University of New South Wales, ADFA, Canberra Contents The League and global politics beyond the Empire-Commonwealth . 2 The requirements of membership ...................................................... 3 The Australian experience as a League mandatory ............................ 4 Peace, disarmament, collective security ............................................. 6 The League and the management of international trade and economic policy ................................................................................ 10 The League’s social agenda ............................................................... 11 Geneva as a school for international affairs for some prominent Australians ......................................................................................... 12 The Australian League of Nations Union........................................... 13 The League idea in Australia ............................................................. 14 Discussion of the League in the parliament and the debate on foreign affairs .................................................................................... 16 Conclusions: Australia in the League ................................................ 19 ISSN 2203-5249 The League and global politics beyond the Empire-Commonwealth With the formation of the Australian Commonwealth, the new nation adopted a constitution that imparted to the -

The Prime Ministers' Partners

The Prime Ministers' Partners "A view is held, and sometimes expressed…that wives of Prime Ministers are more highly regarded and widely loved than Prime Ministers themselves, both during and after their terms of office." - Gough Whitlam "Tim Mathieson is the first bloke of Australia. We know this because he has a jacket to prove it." – Malcolm Farr, 2012 No. Prime Minister’s spouse Previous Partner of Children1 name 1. Jane (Jeanie) BARTON Ross Edmund BARTON 4 sons, 2 daughters 2. Elizabeth (Pattie) DEAKIN Browne Alfred DEAKIN 3 daughters 3. Ada WATSON Low Chris WATSON None 4. Florence (Flora) REID Brumby George REID 2 sons, 1 daughter 5. Margaret FISHER Irvine Andrew FISHER 5 sons, 1 daughter 6. Mary COOK Turner Joseph COOK 6 sons, 3 daughters 7. Mary HUGHES Campbell Billy HUGHES 1 daughter 8. Ethel BRUCE Anderson Stanley BRUCE None 9. Sarah SCULLIN McNamara Jim SCULLIN None 10. Enid LYONS Burnell Joseph LYONS 6 sons, 6 daughters 11. Ethel PAGE Blunt Earle PAGE 4 sons, 1 daughter 12. Pattie MENZIES Leckie Robert MENZIES 2 sons, 1 daughter 13. Ilma FADDEN Thornber Arthur FADDEN 2 sons, 2 daughters 14. Elsie CURTIN Needham John CURTIN 1 son, 1 daughter 15. Veronica (Vera) FORDE O’Reilley Frank FORDE 3 daughters, 1 son 16. Elizabeth CHIFLEY McKenzie Ben CHIFLEY None 17. (Dame) Zara HOLT Dickens Harold HOLT 3 sons 18. Bettina GORTON Brown John GORTON 2 sons, 1 daughter 19. Sonia McMAHON Hopkins William McMAHON 2 daughters, 1 son 20. Margaret WHITLAM Dovey Gough WHITLAM 3 sons, 1 daughter 21. Tamara (Tamie) FRASER Beggs Malcolm FRASER 2 sons, 2 daughters 22. -

Coversheet for Thesis in Sussex Research Online

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Sussex Research Online A University of Sussex DPhil thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details Children of the Red Flag Growing Up in a Communist Family During the Cold War: A Comparative Analysis of the British and Dutch Communist Movement Elke Marloes Weesjes Dphil University of Sussex September 2010 1 Statement I hereby declare that this thesis has not been and will not be, submitted in whole or in part to another University for the award of any other degree. Signature:……………………………………… 2 Abstract This thesis assesses the extent of social isolation experienced by Dutch and British ‘children of the red flag’, i.e. people who grew up in communist families during the Cold War. This study is a comparative research and focuses on the political and non-political aspects of the communist movement. By collating the existing body of biographical research and prosopographical literature with oral testimonies this thesis sets out to build a balanced picture of the British and Dutch communist movement. -

Recorder Vol. 1 No. 2 September 1964

oa ros Recorder <> MELBOURNE BRANCH AUSTRALIAN SOCIETY FOR THE STUDY OF LABOUR HISTORY Vol 1. No. 2. September 19SL EDITORIAL productionDrnfinot-inS ,?,was not+ commencedall we would with wish the for. previous This issueissue andwill the come standard through of production^'^'^^ Letter. Cost is a factor in the andQnr^ anyon^r ??++little will helpfpom to Othergenerate members collective v;ill he activity,v/elcomed immediatelyin return vou may secure a "missing linlc" long sought. x y, la reiiurn you Street,Q+v,^ + Moonee Ponds. should he sent to S. xMerrifield, 81 VVaverley THE ItNfTERNATIONALS 28/q/lfifih^«t^Q? founding of the First International on in humanhnmon >.?history + which ^have ^ ^resulted J^ondon. from It this.is hard' to SiSSess the changes 10711871 were other signs of future17S2, events. 1830, 181+8 and the later Commune of tnto ■Pnr.mform an associationsarly _ as 1839, in London,German worlcnen expelled from Paris attempted giveffivc. ao lead to anotherMarx and efx.ort Engels in produced international the "Communist co-operation. Manifesto" to ff nvp ininternational London at the meetings, time of thetwo 1862 on 28A/1863Exhibition and Government\ in supportSt.James of the Hall Polish demanded insurrection the intervention agains? CzLis? hy the pSIsifEnglish Classes , rmed in I800 oy the karquessMaterial Townshend, Elevation gave aof furtherthe Industrial lead, P^^liifii^inry meetings in June and July were followed hv thP l5/7/18ys"°*^®'' ''•®- dtlesatos only was held at Philadelphia on in Ootobe5°1881°Sto X ao Ohor?nd^??nal?rw''"r?^'"Jonur anu iinally was held in Paris on lh/7/1889. -

The Red North

The Red North Queensland’s History of Struggle Jim McIlroy 2 The Red North: Queensland’s History of Struggle Contents Introduction................................................................................................3 The Great Shearers’ Strikes of the 1890s ....................................5 Maritime Strike................................................................................................. 6 1891 battleground............................................................................................. 8 1894: the third round...................................................................................... 11 Lessons of the 1890s strikes........................................................................... 11 The Red Flag Riots, Brisbane 1919 ..............................................13 Background to the 1919 events...................................................................... 13 ‘Loyalist’ pogrom............................................................................................ 16 The Red North.........................................................................................19 Weil’s Disease................................................................................................. 20 Italian migrants............................................................................................... 21 Women........................................................................................................... 22 Party press..................................................................................................... -

Communism and the Australian Labour Movement 1920-1955

Robin Gollan RevolutionariesGollan • and ReformistsRobin Communism has played a central part in Australian political nightmares for over half a century. Yet it has received scant serious attention comparable in scope and perspec tive with this work. This book places the Communist Party of Australia firmly in its political context, national and international, from the 1920s to the mid-1950s. It is important in its in sights into the general history of Australian radicalism; its contribution to Australian history, especially labour history; and its placing of radical Australian history in a Communism and the Australian Labour world context. It is written from the per spective of one who joined the Communist Movement 1920-1955 Party of Australia because it seemed the only party 'committed to the struggle for socialism and against fascism' and who left it because Robin Gollan this 'no longer seemed the case'. Its breadth, perceptiveness, and understanding com mend it to all people concerned w ith the con tinuing political struggles of the Right, the Left, and the Centre. Robin Gollan RevolutionariesGollan • and ReformistsRobin Communism has played a central part in Australian political nightmares for over half a century. Yet it has received scant serious attention comparable in scope and perspec tive with this work. This book places the Communist Party of Australia firmly in its political context, national and international, from the 1920s to the mid-1950s. It is important in its in sights into the general history of Australian radicalism; its contribution to Australian history, especially labour history; and its placing of radical Australian history in a Communism and the Australian Labour world context. -

Forging a Communist Party for Australia: 1920–1923

Section 1 Forging a Communist Party for Australia: 1920–1923 The documents in this section cover the period from April 1920 to late 1923, that is, from before the inaugural conference of Australian communists to a time when the CPA had emerged as the Australian section of the Comintern, but was still dealing with issues of unity, and was coming to terms with the realities of being a section of a world revolutionary party. The main theme of this section is organizational unity, because that is what the Australian communists and their Comintern colleagues saw as the chief priority. As the ECCI wrote to the feuding Australian communists in June 1922: `The existence of two small groups, amidst a seething current of world shaking events, engaged almost entirely in airing their petty differences, instead of unitedly plunging into the current and mastering it, is not only a ridiculous and shameful spectacle, but also a crime committed against the working class movement' (see Document 15). The crucial unity meeting finally occurred in July that year. The CAAL documents reveal that the Comintern played a larger role in forging the CPA than has previously been thought. There were supporters of the Bolshevik Revolution in Australia, and people who wanted to create a party like the Bolsheviks', to be sure, but Petr Simonov, Paul Freeman and Aleksandr Zuzenko helped to bring the at first waryÐand later squabblingÐcurrents of former Wobblies, former ASP socialists, and former worker radicals together. Indeed the ASP believed that it (the ASP) was, or ought to be, the Australian communist party, and it somewhat begrudgingly went through the unity process demanded by the Comintern. -

Traits and Trends of Australia's Prime Ministers, 1901 to 2015: a Quick Guide

RESEARCH PAPER SERIES, 2015–16 19 JANUARY 2016 Traits and trends of Australia’s prime ministers, 1901 to 2015: a quick guide Dr Joy McCann Politics and Public Administration Section Introduction • This Quick Guide presents information about the backgrounds and service of Australia’s 29 prime ministers, from Edmund Barton to Malcolm Turnbull. It includes information about of their backgrounds (age, place of birth, gender and occupational background), period in office, experience in other parliaments, parties, electorates and military service. • The majority of Australia’s prime ministers have been Australian-born, middle-aged, tertiary-educated men with experience in law or politics, representing electorates in either Victoria or New South Wales. Only one woman has served as Prime Minister since Federation. • Australia’s prime ministers have ranged in age at the time of first taking office from 39 years to 67 years. The average age is 52 years, which reflects the age profile of Australian parliamentarians more generally (51 years). • Three-quarters of Australia’s 29 prime ministers (22) were born in Australia. Of those born overseas, all but one came from the United Kingdom (England, Scotland or Wales). The only non-British overseas-born Prime Minister was Chris Watson, who was born in Chile and raised in New Zealand. Of those born in Australia, the majority were born in either Victoria (nine) or New South Wales (eight). • Thirteen prime ministers have represented electorates in New South Wales, 11 in Victoria, four in Queensland and one each in Western Australia and Tasmania. There have been no prime ministers representing electorates in South Australia, the Northern Territory, or the Australian Capital Territory. -

Earle Page and the Imagining of Australia

‘NOW IS THE PSYCHOLOGICAL MOMENT’ EARLE PAGE AND THE IMAGINING OF AUSTRALIA ‘NOW IS THE PSYCHOLOGICAL MOMENT’ EARLE PAGE AND THE IMAGINING OF AUSTRALIA STEPHEN WILKS Ah, but a man’s reach should exceed his grasp, Or what’s a heaven for? Robert Browning, ‘Andrea del Sarto’ The man who makes no mistakes does not usually make anything. Edward John Phelps Earle Page as seen by L.F. Reynolds in Table Talk, 21 October 1926. Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] Available to download for free at press.anu.edu.au ISBN (print): 9781760463670 ISBN (online): 9781760463687 WorldCat (print): 1198529303 WorldCat (online): 1198529152 DOI: 10.22459/NPM.2020 This title is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). The full licence terms are available at creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode This publication was awarded a College of Arts and Social Sciences PhD Publication Prize in 2018. The prize contributes to the cost of professional copyediting. Cover design and layout by ANU Press. Cover photograph: Earle Page strikes a pose in early Canberra. Mildenhall Collection, NAA, A3560, 6053, undated. This edition © 2020 ANU Press CONTENTS Illustrations . ix Acknowledgements . xi Abbreviations . xiii Prologue: ‘How Many Germans Did You Kill, Doc?’ . xv Introduction: ‘A Dreamer of Dreams’ . 1 1 . Family, Community and Methodism: The Forging of Page’s World View . .. 17 2 . ‘We Were Determined to Use Our Opportunities to the Full’: Page’s Rise to National Prominence .