Varieties & Species Compared

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind. -

Karaoke Catalog Updated On: 09/04/2018 Sing Online on Entire Catalog

Karaoke catalog Updated on: 09/04/2018 Sing online on www.karafun.com Entire catalog TOP 50 Tennessee Whiskey - Chris Stapleton My Way - Frank Sinatra Wannabe - Spice Girls Perfect - Ed Sheeran Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Broken Halos - Chris Stapleton Sweet Caroline - Neil Diamond All Of Me - John Legend Sweet Child O'Mine - Guns N' Roses Don't Stop Believing - Journey Jackson - Johnny Cash Thinking Out Loud - Ed Sheeran Uptown Funk - Bruno Mars Wagon Wheel - Darius Rucker Neon Moon - Brooks & Dunn Friends In Low Places - Garth Brooks Fly Me To The Moon - Frank Sinatra Always On My Mind - Willie Nelson Girl Crush - Little Big Town Zombie - The Cranberries Ice Ice Baby - Vanilla Ice Folsom Prison Blues - Johnny Cash Piano Man - Billy Joel (Sittin' On) The Dock Of The Bay - Otis Redding Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Turn The Page - Bob Seger Total Eclipse Of The Heart - Bonnie Tyler Ring Of Fire - Johnny Cash Me And Bobby McGee - Janis Joplin Man! I Feel Like A Woman! - Shania Twain Summer Nights - Grease House Of The Rising Sun - The Animals Strawberry Wine - Deana Carter Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley At Last - Etta James I Will Survive - Gloria Gaynor My Girl - The Temptations Killing Me Softly - The Fugees Jolene - Dolly Parton Before He Cheats - Carrie Underwood Amarillo By Morning - George Strait Love Shack - The B-52's Crazy - Patsy Cline I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys In Case You Didn't Know - Brett Young Let It Go - Idina Menzel These Boots Are Made For Walkin' - Nancy Sinatra Livin' On A Prayer - Bon -

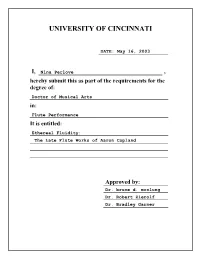

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI DATE: May 16, 2003 I, Nina Perlove , hereby submit this as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctor of Musical Arts in: Flute Performance It is entitled: Ethereal Fluidity: The Late Flute Works of Aaron Copland Approved by: Dr. bruce d. mcclung Dr. Robert Zierolf Dr. Bradley Garner ETHEREAL FLUIDITY: THE LATE FLUTE WORKS OF AARON COPLAND A thesis submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS (DMA) in the Division of Performance Studies of the College-Conservatory of Music 2003 by Nina Perlove B.M., University of Michigan, 1995 M.M., University of Cincinnati, 1999 Committee Chair: bruce d. mcclung, Ph.D. ABSTRACT Aaron Copland’s final compositions include two chamber works for flute, the Duo for Flute and Piano (1971) and Threnodies I and II (1971 and 1973), all written as memorial tributes. This study will examine the Duo and Threnodies as examples of the composer’s late style with special attention given to Copland’s tendency to adopt and reinterpret material from outside sources and his desire to be liberated from his own popular style of the 1940s. The Duo, written in memory of flutist William Kincaid, is a representative example of Copland’s 1940s popular style. The piece incorporates jazz, boogie-woogie, ragtime, hymnody, Hebraic chant, medieval music, Russian primitivism, war-like passages, pastoral depictions, folk elements, and Indian exoticisms. The piece also contains a direct borrowing from Copland’s film scores The North Star (1943) and Something Wild (1961). -

The 'Darkening Sky': French Popular Music of the 1960S and May 1968

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Honors College Winter 12-2016 The ‘Darkening Sky’: French Popular Music of the 1960s and May 1968 Claire Fouchereaux University of Maine Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/honors Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Fouchereaux, Claire, "The ‘Darkening Sky’: French Popular Music of the 1960s and May 1968" (2016). Honors College. 432. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/honors/432 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ‘DARKENING SKY’: FRENCH POPULAR MUSIC OF THE 1960S AND MAY 1968 AN HONORS THESIS by Claire Fouchereaux A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for a Degree with Honors (History) The Honors College University of Maine December 2016 Advisory Committee: Frédéric Rondeau, Assistant Professor of French, Advisor François Amar, Professor of Chemistry and Dean, Honors College Nathan Godfried, Adelaide & Alan Bird Professor of History Jennifer Moxley, Professor of English Kathryn Slott, Associate Professor of French © 2016 Claire Fouchereaux All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT This thesis explores the relationship between ideas, attitudes, and sentiments found in popular French music of the 1960s and those that would later become important during the May 1968 protests in France. May 1968 has generated an enormous amount of literature and analyses of its events, yet there has been little previous work on popular music prior to May 1968 and the events of these protests and strikes that involved up to seven million people at its height. -

Patrick Leterme & Okilélé

LE MAGAZINE DE L’ACTUALITÉ MUSICALE EN FÉDÉRATION WALLONIE-BRUXELLES N° 14 - SEPTEMBRE / OCTOBRE 2015 Patrick Leterme & Okilélé C LAUDE PONTI, DES ENFANTS, UN OPÉRA ! GONZO | THE NAMES | LE COLLECTIF DU LION MICHEL WINTER | LE REFLEKTOR | KRIS DANE Concerts Blondin & Dj Eskondo Exodarap / Blondy Brownie / C.A.R. / Castus / Elle & Samuel / elsie dx / Erwan#Erwan / Jack le Coiffeur / L’Hexaler / La Liesse feat. La Détente Générale, Crash & Freezy / La Mverte / Lia / Marc Melià / Mountain Bike / Nowadays Party feat. La Fine Equipe dj set, Douchka, Food for ya Soul, Yann Kesz / One Man Party / PELICAN / Petal live / Romain Cupper / Romare live / Ropoporose / Shiko Shiko / Solids / Sônge / Théo Hakola / Useless Eaters / Wuman / Wyatt.E / YellowStraps Concerts Sauvages Cobra / It It Anita / Douchka avec la section Synchro du Liège Mosan à la piscine Et aussi de nombreuses activités Picnic urbain au Théâtre de Liège / Liège’s Marché Vintage / DJ Sonar présente La Barbe Mobile / Fresque monumentale par Hell’o Monsters en partenariat avec “l’Open Street Festival” / Sunday Rootsday / Jeudredi CU Juke-box Party / Ça Balance électro présente BPM_intro : rencontres électroniques avec Herrmutt Lobby présente “Playground”, Dan Lacksman Telex, Ssaliva … / Accès aux expositions Wild open SPACE, Jeux de miroir / Lecture en partenariat avec “Les Parlantes” / Installation par “Visuel Hors Service” / Projection du film “We are a one-man band” / Exposition photo / Bons plans bouffe / ... Bracelet pour le festival : 15 € en prévente Programme complet : www.cufestival.be Parcours créatif au coeur de Liège illustration : hell’o monsters 10 - 13 septembre 2015 Musiscope est un service du Conseil de la Musique dont les missions sont de conseiller et apporter de l’information aux acteurs du secteur des musiques en Fédération Wallonie-Bruxelles. -

REGLEMENT Jeu « Sony Days 2018 »

REGLEMENT Jeu « Sony Days 2018 » Article 1. - Sociétés Organisatrices Sony Interactive Entertainment ® France SAS, au capital de 40 000 €, enregistrée au RCS de Nanterre sous le N° 399 930 593, située 92 avenue de Wagram, 75017 Paris ; Sony Mobile Communications, enregistrée au RCS de Nanterre sous le n°439 961 905, située 49-51 quai de Dion Bouton 92800 Puteaux ; Sony Pictures Home Entertainment France SNC, au capital de 107 500 €, enregistrée au RCS de Nanterre en date du 02/03/1987 sous le N° 324 834 266, située 25 quai Gallieni, 92150 Suresnes ; Sony Music Entertainment, France, SAS au capital de 2.524.720 €, enregistrée au RCS de Paris sous le n°542 055 603, située 52/54, rue de Châteaudun, 75009 Paris ; SONY France , succursale de Sony Europe Limited, 49-51 quai de Dion Bouton 92800 Puteaux , RCS Nanterre 390 711 323 (ci-après les « Sociétés Organisatrices ») ; organise un jeu avec obligation d’achat uniquement dans les magasins Fnac et Darty ainsi que sur le sites www.fnac.com et www.darty.com (ci-après le « Jeu ») par le biais d’instants gagnants ouverts du 02/04/2018 10h au 15/04/2018 23h59 inclus ouvert aux personnes physiques majeures (sous réserve des dispositions indiquées à l’article 2) résidant en France Métropolitaine (Corse et DROM-COM exclus). Article 2. - Participation Ce jeu est ouvert à toute personne physique majeure, résidant en France métropolitaine (Corse et DROM-COM exclus), à l'exception des mineurs, du personnel de la société organisatrice et des membres des sociétés partenaires de l'opération ainsi que de leur famille en ligne directe. -

Songs by Artist

3 Jokers Karaoke Songs by Artist French Karaoke Title Title Title 1001 Nuits Alain Barriere Alain Morisod & Sweet People A Quoi Bon Et Tu Fermes Les Yeux Heureus'ment Y'a La Radio Td Tu Me Manques Depuis Longtemps La Marie Joconde Hymne Au Printemps Td 10cc La Terre Tournera Sans Nous Je T'attendrai My Love Productions Donna Les Guinguettes Cuteboy 11-30 Ma Vie La Cabane A Danser Any Man Of Mine Ole Ole Nobody But You Lldd 1755 Plus Je T'entend La Plus Belle Histoire De Ma Vie Musidan Boire Ma Bouteille Qu'elle Disait L'arbre Et L'enfant (Td) Cb Buddie Rien Qu'un Homme Le Bar A Jules Beaulieu Le Gros Party Seduction 13 Le Pardon (Dccdg) Le Jardinier Du Couvent Si Tu Ne Me Revenais Pas Les Violons D'acadie Le Monde A Bien Change Si Tu Te Rappelles Ma Vie Maria Dolores Pecher Aux Iles Si Tu Te Souviens Mon Dernier Amour (Td) U.I.C. Toi No More Bolero Vivre A La Baie Tu T'en Vas Noel Sans Toi (Dccdg) 2be3 Alain Barriere & Nicole Croisille Oui Devant Dieu (Td) Aucune Fille Au Monde Tu T'en Vas Petit Vieux Petite Vieille (Td) Donne Alain Bashung Prends Le Temps (Td) La Salsa Gaby Oh Gaby Puisque Tu Pars Partir Un Jour Osez Josephine River Blue Toujours La Pour Toi Vertige De L'amour Riverblue Abbittibbi Alain Chamfort Sans Toi Cryin' Boomtown Cafe La Musique Du Samedi Un Enfant Rene Rose Aimee Madona Madona Une Chanson Italienne (Andre00) Adamo Un Coin De Vie Voila Pourquoi On Chante Rene A Votre Bon Coeur Monsieur Alain Delorme Alain Souchon Inch'allah Et Surtout Ne M'oublie Pas Allo Maman Bobo J'avais Oublie Que Les Roses Sont J'ai Un Petit -

Dynamic Curves and Poetic Lyricism in Selected Chansons of Jacques Brel

Copyright by Justin Marc Joshua Weyn-Vanhentenryck 2020 The Report Committee for Justin Marc Joshua Weyn-Vanhentenryck Certifies that this is the approved version of the following Report: Dynamic Curves and Poetic Lyricism in Selected Chansons of Jacques Brel APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Robert S. Hatten, Supervisor John R. Turci-Escobar, Co-Supervisor Dynamic Curves and Poetic Lyricism in Selected Chansons of Jacques Brel by Justin Marc Joshua Weyn-Vanhentenryck Report Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Music The University of Texas at Austin August, 2020 Acknowledgements I extend my deepest gratitude to my parents, Chris and Catherine, whose continuous support made this project possible. Thank you to my brothers Sébastien and Jonathan, as well as to Lauren—my future sister-in-law—for their laughter, support, and occasional video game soirées. Most heartfelt thanks to Professor John Turci-Escobar, my report advisor, for his valuable guidance and knowledge of popular music culture and theory. A special thank-you to Professor Robert Hatten for his particularly insightful comments as well as for the generous travel grant from his Meyerson Professorship research fund, which allowed me to visit Brussels in March of 2020 as part of my research at the Brel Foundation. Finally, a huge thank-you to Professor Francis de Laveleye, France Brel, and the Brel Foundation in Brussels for giving me access to so many resources and archives. iv Abstract Dynamic Curves and Poetic Lyricism in Selected Chansons of Jacques Brel Justin Marc Joshua Weyn-Vanhentenryck, M.MUSIC The University of Texas at Austin, 2020 Supervisor: Robert S. -

Catalogue Karaoké Mis À Jour Le: 22/08/2018 Chantez En Ligne Sur Catalogue Entier

Catalogue Karaoké Mis à jour le: 22/08/2018 Chantez en ligne sur www.karafun.fr Catalogue entier TOP 50 Bella Ciao - Maître Gims Place des grands hommes - Patrick Bruel Les yeux de la mama - Kendji Girac Je te promets - Johnny Hallyday Andalouse - Kendji Girac Alexandrie Alexandra - Claude François Sous le vent - Garou Les sunlights des tropiques - Gilbert Montagné Sensualité - Axelle Red Libérée, délivrée - Frozen La tribu de Dana - Manau Encore un soir - Céline Dion Les démons de minuit - Images L'envie d'aimer - Les Dix Commandements Ce rêve bleu - Aladdin La même - Maître Gims Cette année-là - Claude François Sur ma route - Black M Mistral gagnant - Renaud L'oiseau et l'enfant - Kids United Le Jerk - Thierry Hazard J'irai où tu iras - Céline Dion Perfect - Ed Sheeran Femme libérée - Cookie Dingler On va s'aimer - Gilbert Montagné J't'emmène au vent - Louise Attaque La bohème - Charles Aznavour On écrit sur les murs - Kids United Je te donne - Jean-Jacques Goldman Cendrillon - Téléphone Allumer le feu - Johnny Hallyday Chocolat - Lartiste Il est où le bonheur - Christophe Maé Manhattan-Kaboul - Renaud Emmenez-moi - Charles Aznavour Santiano (version 2010) - Hugues Aufray Vivo per lei - Andrea Bocelli L'aventurier - Indochine Là-bas - Jean-Jacques Goldman Dommage - Bigflo & Oli Mon mec à moi - Patricia Kaas Armstrong - Claude Nougaro Les Champs-Élysées - Joe Dassin Despacito - Luis Fonsi Le chanteur - Daniel Balavoine Pour que tu m'aimes encore - Céline Dion J'ai encore rêvé d'elle - Il était une fois Femme que j'aime - Jean-Luc Lahaye -

Europe Travelogue September 4 to 27, 2015

EUROPE TRAVELOGUE SEPTEMBER 4 TO 27, 2015 So, we embark on yet another "adventure." By the time we return to the U.S., we will have visited no fewer than seven European countries, albeit some of them for just the short time that it takes to change planes. We'll fly on Delta/KLM nonstop from Seattle to Amsterdam and transfer to another Delta/KLM plane that will take us to Venice. W e'll spend three evenings in Venice, then board an Adriatic cruise ship that will stop at several ports in Croatia and one in Montenegro. Upon our return to Venice, we'll fly on Swiss Global Air to Zurich, where we will rent a car and drive north to Germany's Black Forest for five days. We'll then drive to Lyon where we will board a Rhône cruise ship that will take us to Avignon. From the nearby Marseille airport, we'll fly on a Delta/Air France plane to Amsterdam and from there back to the U.S. Assuming that all goes as planned, that is. In my many earlier travelogs, I've paid tribute to my wife for her brilliant planning of our journey. This time, however, most of the work was done by our intrepid travel agent (Stefan Bisciglia of Specialty Cruise and Villas, a fam ily-run travel agency in Gig Harbor), who reserved our cabins on the Tauck and Uniworld cruise ships, booked us for an extra night at the hotel in Venice, m ade the reservations at two hotels in Germany, and arranged for all of the plane tickets and seat reservations. -

SECESSION: International Law Perspectives

This page intentionally left blank SECESSION TheendoftheColdWarbroughtaboutnewsecessionistaspirationsandthe strengthening and re-awakening of existing or dormant separatist claims everywhere. The creation of a new independent entity through the separa- tion of part of the territory and population of an existing State raises serious difficulties as to the role of international law. This book offers a compre- hensive study of secession from an international law perspective, focusing on recent practice and applicable rules of contemporary international law. It includes theoretical analyses and a scrutiny of practice throughout the world byeighteen distinguished authors from Western and Eastern Europe, North and Sub-Saharan Africa, North and Latin America, and Asia. Core questions are addressed from different perspectives, and in some cases with divergent views. The reader is also exposed to a far-reaching picture of State practice, including some cases which are rarely mentioned and often neglected in scholarly analysis of secession. marcelo g.kohenis Professor of International Law at the Graduate Institute of International Studies, Geneva. SECESSION International Law Perspectives Edited by MARCELO G. KOHEN cambridge university press Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, São Paulo Cambridge University Press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge cb2 2ru,UK Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York www.cambridge.org Informationonthistitle:www.cambridge.org/9780521849289 © Cambridge -

“There Is Helen in the Lime-Walk,” Said Mrs. Collingwood to Her Husband, As She Looked out of the Window

1 HELEN MARIA EDGEWORTH VOLUME THE FIRST. CHAPTER 1. “There is Helen in the lime-walk,” said Mrs. Collingwood to her husband, as she looked out of the window. The slight figure of a young person in deep mourning appeared between the trees — “How slowly she walks! She looks very unhappy!” “Yes,” said Mr. Collingwood, with a sigh, “she is young to know sorrow, and to struggle with difficulties to which she is quite unsuited both by nature and by education, difficulties which no one could ever have foreseen. How changed are all her prospects!” “Changed indeed!” said Mrs. Collingwood, “pretty young creature! — Do you recollect how gay she was when first we came to Cecilhurst? and even last year, when she had hopes of her uncle’s recovery, and when he talked of taking her to London, how she enjoyed the thoughts of going there! The world was bright before her then. How cruel of that uncle, with all his fondness for her, never to think what was to become of her the moment he was dead: to breed her up as an heiress, and leave her a beggar!” “But what is to be done, my dear?” said her husband. “I am sure I do not know; I can only feel for her, you must think for her.” “Then I think I must tell her directly of the state in which her uncle’s affairs are left, and that there is no provision for her.” “Not yet, my dear,” said Mrs. Collingwood: “I don’t mean about there being no provision for herself, that would not strike her, but her uncle’s debts — there is the point: she would feel dreadfully the disgrace to his memory — she loved him so tenderly!” “Yet it must be told,” said Mr.