Poulenc's Development As a Piano Composer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

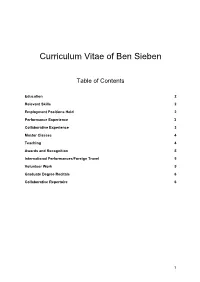

Curriculum Vitae of Ben Sieben

Curriculum Vitae of Ben Sieben Table of Contents Education 2 Relevant Skills 2 Employment Positions Held 2 Performance Experience 3 Collaborative Experience 3 Master Classes 4 Teaching 4 Awards and Recognition 5 International Performances/Foreign Travel 5 Volunteer Work 5 Graduate Degree Recitals 6 Collaborative Repertoire 6 1 BEN SIEBEN [email protected] | 979-479-1197 | 61 San Jacinto St., Bay City, TX, 77414 Education Master of Music in Collaborative Piano 2017 University of Colorado Boulder Primary instructors: Margaret McDonald and Alexandra Nguyen Master of Music in Piano Performance 2012 University of Utah Primary instructor: Heather Conner Bachelor of Music in Piano Performance 2010 Houston Baptist University Primary instructor: Melissa Marse Relevant Skills 25 years of classical piano sight reading improvisation open-score reading transposition jazz and rock styles basso-continuo harpsichord music theory score arranging transcription by ear reading lead sheets keyboard/synthesizer proficiency Italian, German, French, and English diction fluent conversational Spanish Employment Positions Held Emerging Musical Artist-in-Residence, Penn State Altoona 2017 Vocal coach and accompanist for private voice students Graduate Assistant, University of Colorado Boulder 2015-2017 Collaborative pianist, pianist for instrumental students, vocal students, orchestra, opera, and opera scenes classes Choral Accompanist, Texas A&M University 2012-2015 Accompanist for Century Singers and Women’s Chorus Choral Accompanist, Brazos Valley Chorale -

La Voix Humaine: a Technology Time Warp

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Music Music 2016 La Voix humaine: A Technology Time Warp Whitney Myers University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: http://dx.doi.org/10.13023/ETD.2016.332 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Myers, Whitney, "La Voix humaine: A Technology Time Warp" (2016). Theses and Dissertations--Music. 70. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/music_etds/70 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Music by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. I agree that the document mentioned above may be made available immediately for worldwide access unless an embargo applies. -

Focus 2020 Pioneering Women Composers of the 20Th Century

Focus 2020 Trailblazers Pioneering Women Composers of the 20th Century The Juilliard School presents 36th Annual Focus Festival Focus 2020 Trailblazers: Pioneering Women Composers of the 20th Century Joel Sachs, Director Odaline de la Martinez and Joel Sachs, Co-curators TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction to Focus 2020 3 For the Benefit of Women Composers 4 The 19th-Century Precursors 6 Acknowledgments 7 Program I Friday, January 24, 7:30pm 18 Program II Monday, January 27, 7:30pm 25 Program III Tuesday, January 28 Preconcert Roundtable, 6:30pm; Concert, 7:30pm 34 Program IV Wednesday, January 29, 7:30pm 44 Program V Thursday, January 30, 7:30pm 56 Program VI Friday, January 31, 7:30pm 67 Focus 2020 Staff These performances are supported in part by the Muriel Gluck Production Fund. Please make certain that all electronic devices are turned off during the performance. The taking of photographs and use of recording equipment are not permitted in the auditorium. Introduction to Focus 2020 by Joel Sachs The seed for this year’s Focus Festival was planted in December 2018 at a Juilliard doctoral recital by the Chilean violist Sergio Muñoz Leiva. I was especially struck by the sonata of Rebecca Clarke, an Anglo-American composer of the early 20th century who has been known largely by that one piece, now a staple of the viola repertory. Thinking about the challenges she faced in establishing her credibility as a professional composer, my mind went to a group of women in that period, roughly 1885 to 1930, who struggled to be accepted as professional composers rather than as professional performers writing as a secondary activity or as amateur composers. -

Francis Poulenc and Surrealism

Wright State University CORE Scholar Master of Humanities Capstone Projects Master of Humanities Program 1-2-2019 Francis Poulenc and Surrealism Ginger Minneman Wright State University - Main Campus Follow this and additional works at: https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/humanities Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Repository Citation Minneman, G. (2019) Francis Poulenc and Surrealism. Wright State University, Dayton, Ohio. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master of Humanities Program at CORE Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master of Humanities Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of CORE Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Minneman 1 Ginger Minneman Final Project Essay MA in Humanities candidate Francis Poulenc and Surrealism I. Introduction While it is true that surrealism was first and foremost a literary movement with strong ties to the world of art, and not usually applied to musicians, I believe the composer Francis Poulenc was so strongly influenced by this movement, that he could be considered a surrealist, in the same way that Debussy is regarded as an impressionist and Schönberg an expressionist; especially given that the artistic movement in the other two cases is a loose fit at best and does not apply to the entirety of their output. In this essay, which served as the basis for my lecture recital, I will examine some of the basic ideals of surrealism and show how Francis Poulenc embodies and embraces surrealist ideals in his persona, his music, his choice of texts and his compositional methods, or lack thereof. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 71, 1951

BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA SEVENTY-FIRST SEASON 1951-1952 Veterans Memorial Auditorium, Providence Boston Symphony Orchestra (Seventy-first Season, 1951-1952) CHARLES MUNCH, Music Director RICHARD BURGIN, i4550ciate Conductor PERSONNEL Violins Violas Bassoons Richard Biirgin, Joseph de Pasquale Raymond AUard Concert -master Jean Cauhap6 Ernst Panenka Alfred Krips Georges Fourel Theodore Brewster Gaston Elcus Eugen Lehner Rolland Tapley Albert Bernard Contra-Bassoon Norbert Lauga George Humphrey Boaz Piller George Zazofsky Jerome Lipson Louis Arti^res Paul Cherkassky Horns Harry Dubbs Robert Karol Reuben Green James Stagliano Vladimir Resnikoff Harry Shapiro Joseph Leibovici Bernard KadinofI Harold Meek Einar Hansen Vincent Mauricci Paul Keaney Harry Dickson Walter Macdonald V^IOLONCELLOS Erail Kornsand Osbourne McConathy Samuel Mayes Carlos Pinfield Alfred Zighera Paul Fedorovsky Trumpets Minot Beale Jacobus Langendoen Mischa Nieland Roger Voisin Herman Silberman Marcel Lafosse Hippolyte Droeghmans Roger Schermanski Armando Ghitalla Karl Zeise Stanley Benson Gottfried Wilfinger Josef Zimbler Bernard Parronchi Trombones Enrico Fabrizio Raichman Clarence Knudson Jacob Leon Marjollet Lucien Hansotte Pierre Mayer John Coffey Manuel Zung Flutes Josef Orosz Samuel Diamond Georges Laurent Victor Manusevitch Pappoutsakis James Tuba James Nagy Phillip Kaplan Leon Gorodetzky Vinal Smith Raphael Del Sordo Piccolo Melvin Bryant George Madsen Harps Lloyd Stonestrect Bernard Zighera Saverio Messina Oboes Olivia Luetcke Sheldon Rotenbexg Ralph Gomberg -

L'homme Sans Yeux, Sans Nez Et Sans Oreilles by José Soler Casabón

2021,1 Международный отдел • International Division ISSN 1997-0854 (Print), 2587-6341 (Online) DOI: 10.33779/2587-6341.2021.1.075-082 UDC 782.91 SANDRA SOLER CAMPO, JUAN JURADO BRACERO Universidad de Barcelona Taller de Músics ESEM, Barcelona, Spain ORCID: 0000-0002-5560-1415, [email protected] [email protected] The Influence of Russian Ballets in the 20th Century: L’Homme sans yeux, sans nez et sans oreilles by José Soler Casabón and Parade by Érik Satie This article aims at providing a broad appraisal of the figure of José Soler Casabón through one of his main compositions, L'homme sans yeux, sans nez at sans oreilles (Ho.S.Y.N.O.), a ballet based on the poem Le musicien de Saint Merry written by Guillaume Apollinaire with sets by Pablo Picasso. Parade by Erik Satie and Ho.S.Y.N.O. by Soler Casabón, are two ballets created in 1917. The difference between the two works lies in the fate suffered by each as a result of the outbreak of the First World War, which prevented one of them from being performed. Soler Casabón spent the rest of his life trying to have the work see the light of day, but without any success. Keywords: Guillaume Apollinaire, ballet, José Soler Casabón, Paris, Érik Satie, Parade. For citation / Для цитирования: Soler Campo S., Jurado Bracero J. The Influence of Russian Ballets in the 20th Century: L’Homme sans yeux, sans nez et sans oreilles by José Soler Casabón and Parade by Érik Satie // Проблемы музыкальной науки / Music Scholarship. -

November 2016

November 2016 Igor Levit INSIDE: Borodin Quartet Le Concert d’Astrée & Emmanuelle Haïm Imogen Cooper Iestyn Davies & Thomas Dunford Emerson String Quartet Ensemble Modern Brigitte Fassbaender Masterclasses Kalichstein/Laredo/ Robinson Trio Dorothea Röschmann Sir András Schiff and many more Box Office 020 7935 2141 Online Booking www.wigmore-hall.org.uk How to Book Wigmore Hall Box Office 36 Wigmore Street, London W1U 2BP In Person 7 days a week: 10 am – 8.30 pm. Days without an evening concert 10 am – 5 pm. No advance booking in the half hour prior to a concert. By Telephone: 020 7935 2141 7 days a week: 10 am – 7 pm. Days without an evening concert 10 am – 5 pm. There is a non-refundable £3.00 administration fee for each transaction, which includes the return of your tickets by post if time permits. Online: www.wigmore-hall.org.uk 7 days a week; 24 hours a day. There is a non-refundable £2.00 administration charge. Standby Tickets Standby tickets for students, senior citizens and the unemployed are available from one hour before the performance (subject to availability) with best available seats sold at the lowest price. NB standby tickets are not available for Lunchtime and Coffee Concerts. Group Discounts Discounts of 10% are available for groups of 12 or more, subject to availability. Latecomers Latecomers will only be admitted during a suitable pause in the performance. Facilities for Disabled People full details available from 020 7935 2141 or [email protected] Wigmore Hall has been awarded the Bronze Charter Mark from Attitude is Everything TICKETS Unless otherwise stated, tickets are A–D divided into five prices ranges: BALCONY Stalls C – M W–X Highest price T–V Stalls A – B, N – P Q–S 2nd highest price Balcony A – D N–P 2nd highest price STALLS Stalls BB, CC, Q – S C–M 3rd highest price A–B Stalls AA, T – V CC CC 4th highest price BB BB PLATFORM Stalls W – X AAAA AAAA Lowest price This brochure is available in alternative formats. -

Lazzaro Federico 2014 These.Pdf (6.854Mb)

Université de Montréal École(s) de Paris Enquête sur les compositeurs étrangers à Paris dans l’entre-deux-guerres par FEDERICO LAZZARO Faculté de musique Thèse présentée à la Faculté de musique en vue de l’obtention du grade de Docteur en Musique (option Musicologie) Novembre 2014 © Federico Lazzaro, 2014 Résumé « École de Paris » est une expression souvent utilisée pour désigner un groupe de compositeurs étrangers ayant résidé à Paris dans l’entre-deux-guerres. Toutefois, « École de Paris » dénomme des réalités différentes selon les sources. Dans un sens élargi, le terme comprend tous les compositeurs de toute époque ayant vécu au moins une partie de leur vie à Paris. Dans son sens le plus strict, il désigne le prétendu regroupement de quatre à six compositeurs arrivés à Paris dans les années 1920 et comprenant notamment Conrad Beck, Tibor Harsányi, Bohuslav Martinů, Marcel Mihalovici, Alexandre Tansman et Alexandre Tchérepnine. Dans le but de revisiter l’histoire de l’utilisation de cette expression, nous avons reconstitué le discours complexe et contradictoire à propos de la question « qu’est-ce que l’École de Paris? ». Notre « enquête », qui s’est déroulée à travers des documents historiques de l’entre-deux-guerres ainsi que des textes historiographiques et de vulgarisation parus jusqu’à nos jours, nous a mené à la conclusion que l’École de Paris est un phénomène discursif que chaque acteur a pu manipuler à sa guise, car aucun fait ne justifie une utilisation univoque de cette expression dans le milieu musical parisien des années 1920-1930. L’étude de la programmation musicale nous a permis notamment de démontrer qu’aucun évènement regroupant les compositeurs considérés comme des « membres » de l’École de Paris n’a jamais eu lieu entre 1920 et 1940. -

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind. -

Francis Poulenc

CORO CORO Palestrina – Volume 6 “Christophers artfully moulds and heightens the contours of the polyphonic lines, which ebb and flow in a liquid tapestry of sound...[The Sixteen] are ardent and energetic in ‘Surge amica mea’, radiant in ‘Surgam et circuibo FRANCIS POULENC civitatem’, painting and animating the words to vibrant effect.” ***** Performance ***** Recording Mass in G BBC MUSIC MAGAZINE cor16133 Choral & Song Choice October 2015 Un soir de neige James MacMillan: Litanies à la Vierge Noire Stabat Mater Edmund Rubbra “A masterpiece.” “Harry Christophers balances Quatre motets pour artsdesk the soaring soprano of Julie le temps de Noël Cooper caressingly against the ensemble singers, in a “A haunting and Quatre motets pour powerful new performance which achieves choral work.” ecstasy without any element un temps de pénitence of overstatement.” guardian cor16150 cor16144 bbc music magazine To find out more about The Sixteen, concert tours, and to buy CDs visit The Sixteen www.thesixteen.com cor16149 HARRY CHRISTOPHERS oulenc is a composer who has fascinated me Whilst the death of his friend Ferroud had a devastating impact on Poulenc, the poetry Pever since I was a schoolboy struggling with the of Paul Éluard gave him inspiration beyond measure. Poulenc grew up with him and technical difficulties of his clarinet sonata. His music once said that ‘Éluard was my true brother – through him I learned to express the most always bears a human face and he himself felt he put his secret part of myself’. They both felt the savagery of WWII deeply, the social anguish, best and most authentic side into his choral music; the internal conflict and ignominy of the Nazi occupation. -

Understanding Music Past and Present

Understanding Music Past and Present N. Alan Clark, PhD Thomas Heflin, DMA Jeffrey Kluball, EdD Elizabeth Kramer, PhD Understanding Music Past and Present N. Alan Clark, PhD Thomas Heflin, DMA Jeffrey Kluball, EdD Elizabeth Kramer, PhD Dahlonega, GA Understanding Music: Past and Present is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribu- tion-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. This license allows you to remix, tweak, and build upon this work, even commercially, as long as you credit this original source for the creation and license the new creation under identical terms. If you reuse this content elsewhere, in order to comply with the attribution requirements of the license please attribute the original source to the University System of Georgia. NOTE: The above copyright license which University System of Georgia uses for their original content does not extend to or include content which was accessed and incorpo- rated, and which is licensed under various other CC Licenses, such as ND licenses. Nor does it extend to or include any Special Permissions which were granted to us by the rightsholders for our use of their content. Image Disclaimer: All images and figures in this book are believed to be (after a rea- sonable investigation) either public domain or carry a compatible Creative Commons license. If you are the copyright owner of images in this book and you have not authorized the use of your work under these terms, please contact the University of North Georgia Press at [email protected] to have the content removed. ISBN: 978-1-940771-33-5 Produced by: University System of Georgia Published by: University of North Georgia Press Dahlonega, Georgia Cover Design and Layout Design: Corey Parson For more information, please visit http://ung.edu/university-press Or email [email protected] TABLE OF C ONTENTS MUSIC FUNDAMENTALS 1 N. -

California State University, Northridge Jean Cocteau

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE JEAN COCTEAU AND THE MUSIC OF POST-WORLD WAR I FRANCE A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Music by Marlisa Jeanine Monroe January 1987 The Thesis of Marlisa Jeanine Monroe is approved: B~y~ri~jl{l Pfj}D. Nancy an Deusen, Ph.D. (Committee Chair) California State University, Northridge l.l. TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page ABSTRACT iv INTRODUCTION • 1 I. EARLY INFLUENCES 4 II. DIAGHILEV 8 III. STRAVINSKY I 15 IV • PARADE 20 v. LE COQ ET L'ARLEQUIN 37 VI. LES SIX 47 Background • 47 The Formation of the Group 54 Les Maries de la tour Eiffel 65 The Split 79 Milhaud 83 Poulenc 90 Auric 97 Honegger 100 VII. STRAVINSKY II 109 VIII. CONCLUSION 116 BIBLIOGRAPHY 120 APPENDIX: MUSICAL CHRONOLOGY 123 iii ABSTRACT JEAN COCTEAU AND THE MUSIC OF POST-WORLD WAR I FRANCE by Marlisa Jeanine Monroe Master of Arts in Music Jean Cocteau (1889-1963) was a highly creative and artistically diverse individual. His talents were expressed in every field of art, and in each field he was successful. The diversity of his talent defies traditional categorization and makes it difficult to assess the singularity of his aesthetic. In the field of music, this aesthetic had a profound impact on the music of Post-World War I France. Cocteau was not a trained musician. His talent lay in his revolutionary ideas and in his position as a catalyst for these ideas. This position derived from his ability to seize the opportunities of the time: the need iv to fill the void that was emerging with the waning of German Romanticism and impressionism; the great showcase of Diaghilev • s Ballets Russes; the talents of young musicians eager to experiment and in search of direction; and a congenial artistic atmosphere.