The Sorcerer's Apprentice Suite from Les Biches

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Focus 2020 Pioneering Women Composers of the 20Th Century

Focus 2020 Trailblazers Pioneering Women Composers of the 20th Century The Juilliard School presents 36th Annual Focus Festival Focus 2020 Trailblazers: Pioneering Women Composers of the 20th Century Joel Sachs, Director Odaline de la Martinez and Joel Sachs, Co-curators TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction to Focus 2020 3 For the Benefit of Women Composers 4 The 19th-Century Precursors 6 Acknowledgments 7 Program I Friday, January 24, 7:30pm 18 Program II Monday, January 27, 7:30pm 25 Program III Tuesday, January 28 Preconcert Roundtable, 6:30pm; Concert, 7:30pm 34 Program IV Wednesday, January 29, 7:30pm 44 Program V Thursday, January 30, 7:30pm 56 Program VI Friday, January 31, 7:30pm 67 Focus 2020 Staff These performances are supported in part by the Muriel Gluck Production Fund. Please make certain that all electronic devices are turned off during the performance. The taking of photographs and use of recording equipment are not permitted in the auditorium. Introduction to Focus 2020 by Joel Sachs The seed for this year’s Focus Festival was planted in December 2018 at a Juilliard doctoral recital by the Chilean violist Sergio Muñoz Leiva. I was especially struck by the sonata of Rebecca Clarke, an Anglo-American composer of the early 20th century who has been known largely by that one piece, now a staple of the viola repertory. Thinking about the challenges she faced in establishing her credibility as a professional composer, my mind went to a group of women in that period, roughly 1885 to 1930, who struggled to be accepted as professional composers rather than as professional performers writing as a secondary activity or as amateur composers. -

Understanding Music Past and Present

Understanding Music Past and Present N. Alan Clark, PhD Thomas Heflin, DMA Jeffrey Kluball, EdD Elizabeth Kramer, PhD Understanding Music Past and Present N. Alan Clark, PhD Thomas Heflin, DMA Jeffrey Kluball, EdD Elizabeth Kramer, PhD Dahlonega, GA Understanding Music: Past and Present is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribu- tion-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. This license allows you to remix, tweak, and build upon this work, even commercially, as long as you credit this original source for the creation and license the new creation under identical terms. If you reuse this content elsewhere, in order to comply with the attribution requirements of the license please attribute the original source to the University System of Georgia. NOTE: The above copyright license which University System of Georgia uses for their original content does not extend to or include content which was accessed and incorpo- rated, and which is licensed under various other CC Licenses, such as ND licenses. Nor does it extend to or include any Special Permissions which were granted to us by the rightsholders for our use of their content. Image Disclaimer: All images and figures in this book are believed to be (after a rea- sonable investigation) either public domain or carry a compatible Creative Commons license. If you are the copyright owner of images in this book and you have not authorized the use of your work under these terms, please contact the University of North Georgia Press at [email protected] to have the content removed. ISBN: 978-1-940771-33-5 Produced by: University System of Georgia Published by: University of North Georgia Press Dahlonega, Georgia Cover Design and Layout Design: Corey Parson For more information, please visit http://ung.edu/university-press Or email [email protected] TABLE OF C ONTENTS MUSIC FUNDAMENTALS 1 N. -

California State University, Northridge Jean Cocteau

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE JEAN COCTEAU AND THE MUSIC OF POST-WORLD WAR I FRANCE A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Music by Marlisa Jeanine Monroe January 1987 The Thesis of Marlisa Jeanine Monroe is approved: B~y~ri~jl{l Pfj}D. Nancy an Deusen, Ph.D. (Committee Chair) California State University, Northridge l.l. TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page ABSTRACT iv INTRODUCTION • 1 I. EARLY INFLUENCES 4 II. DIAGHILEV 8 III. STRAVINSKY I 15 IV • PARADE 20 v. LE COQ ET L'ARLEQUIN 37 VI. LES SIX 47 Background • 47 The Formation of the Group 54 Les Maries de la tour Eiffel 65 The Split 79 Milhaud 83 Poulenc 90 Auric 97 Honegger 100 VII. STRAVINSKY II 109 VIII. CONCLUSION 116 BIBLIOGRAPHY 120 APPENDIX: MUSICAL CHRONOLOGY 123 iii ABSTRACT JEAN COCTEAU AND THE MUSIC OF POST-WORLD WAR I FRANCE by Marlisa Jeanine Monroe Master of Arts in Music Jean Cocteau (1889-1963) was a highly creative and artistically diverse individual. His talents were expressed in every field of art, and in each field he was successful. The diversity of his talent defies traditional categorization and makes it difficult to assess the singularity of his aesthetic. In the field of music, this aesthetic had a profound impact on the music of Post-World War I France. Cocteau was not a trained musician. His talent lay in his revolutionary ideas and in his position as a catalyst for these ideas. This position derived from his ability to seize the opportunities of the time: the need iv to fill the void that was emerging with the waning of German Romanticism and impressionism; the great showcase of Diaghilev • s Ballets Russes; the talents of young musicians eager to experiment and in search of direction; and a congenial artistic atmosphere. -

Catalogue Chronologique Des Œuvres De Francis Poulenc

CATALOGUE CHRONOLOGIQUE DES ŒUVRES DE FRANCIS POULENC Légende : [œuvre inédite] [œuvre détruite] [œuvre perdue] 1 [Processionnal pour la crémation d’un mandarin] 2 [Préludes pour piano] 1918 3 Rhapsodie nègre, œuvre pour voix et piano 4 [Scherzo à quatre mains] 5 [Trois pastorales pour piano] 6 [Poèmes sénégalais] 1919 7 Sonate pour 2 clarinettes, œuvre de musique de chambre 8 Sonate pour piano à quatre mains, œuvre pour piano 9 [Prélude-percussion] 10 [Le Jongleur] 11 Toréador (Cocteau), œuvre pour voix et piano 12 [Sonate pour violon et piano n°0] 13 [Sonate pour violon, piano et violoncelle] 1920 14 3 Mouvements perpétuels, œuvre pour piano 15 Le Bestiaire (Apollinaire), œuvre pour voix et piano 16 Cocardes (Cocteau), œuvre pour voix et piano 17 Valse 18 [Quadrille à quatre mains] 19 Suite en 3 mouvements, œuvre pour piano 20 Le gendarme incompris, œuvre pour la scène 21 5 Impromptus, œuvre pour piano 1921 22 Quatre poèmes de Max Jacob, œuvre pour voix et piano 23 Les mariés de la Tour Eiffel, œuvre pour orchestre 24 10 Promenades, œuvre pour piano 25 Esquisse pour une fanfare, œuvre pour la scène 26 [Trois études de pianola] 27 [Suite d’orchestre n°1] 28 [Quatuor à cordes n° 1] 29 [Trio pour piano, clarinette et violoncelle] 30 [Marches militaires pour piano et orchestre] 1 1922 31 Chanson à boire, œuvre chorale profane 32 Sonate pour clarinette et basson, œuvre de musique de chambre 33 Trio pour cor, trompette et trombone, œuvre de musique de chambre 34 [« Caprice espagnole »] 1923 35 [Récitatifs pour La Colombe -

Poulenc, Francis (1899-1963) by Mario Champagne

Poulenc, Francis (1899-1963) by Mario Champagne Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. Entry Copyright © 2002, glbtq, Inc. Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com Francis Poulenc with harpsichordist Wanda Landowska. One of the first openly gay composers, Francis Poulenc wrote concerti, chamber music, choral and vocal works, and operas. His diverse compositions are characterized by bright colors, strong rhythms, and novel harmonies. Although his early music is light, he ultimately became one of the most thoughtful composers of serious music in the twentieth century. Poulenc was born on January 7, 1899 into a well-off Parisian family. His father, a devout Roman Catholic, directed the pharmaceutical company that became Rhône-Poulenc; his mother, a free-thinker, was a talented amateur pianist. He began studying the piano at five and was following a promising path leading to admission to the Conservatoire that was cut short by the untimely death of his parents. Although he did not attend the Conservatoire he did study music and composition privately. At the death of his parents, Poulenc inherited Noizay, a country estate near his grandparents' home, which would be an important retreat for him as he gained fame. It was also the source of several men in his life, including his second lover, the bisexual Raymond Destouches, a chauffeur who was the dedicatee of the surrealistic opera Les mamelles de Tirésias (1944) and the World War II Resistance cantata La figure humaine (1943). From 1914 to 1917, Poulenc studied with the Spanish pianist Ricardo Viñes, through whom he met other musicians, especially Georges Auric, Erik Satie, and Manuel de Falla. -

JEAN COCTEAU (1889-1963) Compiled by Curator Tony Clark, Chevalier Dans L’Ordre Des Arts Et Des Lettres

JEAN COCTEAU (1889-1963) Compiled by curator Tony Clark, Chevalier dans l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres 1889 Jean Maurice Clement Cocteau is born to a wealthy family July 5, in Maisons Laffite, on the outskirts of Paris and the Eiffel Tower is completed. 1899 His father commits suicide 1900 - 1902 Enters private school. Creates his first watercolor and signs it “Japh” 1904 Expelled from school and runs away to live in the Red Light district of Marsailles. 1905 - 1908 Returns to Paris and lives with his uncle where he writes and draws constantly. 1907 Proclaims his love for Madeleine Carlier who was 30 years old and turned out to be a famous lesbian. 1908 Published with text and portraits of Sarah Bernhardt in LE TEMOIN. Edouard de Max arranges for the publishing of Cocteau’s first book of poetry ALLADIN’S LAMP. 1909 - 1910 Diaghailev commissions the young Cocteau to create two lithographic posters for the first season of LES BALLETS RUSSES. Cocteau creates illustrations and text published in SCHEHERAZADE and he becomes close friends with Vaslav Nijinsky, Leon Bakst and Igor Stravinsky. 1911 - 1912 Cocteau is commissioned to do the lithographs announcing the second season of LES BALLETS RUSSES. At this point Diaghailev challenges Cocteau with the statement “Etonnez-Moi” - Sock Me. Cocteau created his first ballet libretti for Nijinsky called DAVID. The ballet turned in the production LE DIEU BLU. 1913 - 1915 Writes LE POTOMAK the first “Surrealist” novel. Continues his war journal series call LE MOT or THE WORD. It was to warn the French not to let the Germans take away their liberty or spirit. -

Francis Poulenc Et La Danse Francis Poulenc and the Dance Hervé Lacombe

Document généré le 30 sept. 2021 16:39 Les Cahiers de la Société québécoise de recherche en musique Francis Poulenc et la danse Francis Poulenc and the Dance Hervé Lacombe Danse et musique : Dialogues en mouvement Résumé de l'article Volume 13, numéro 1-2, septembre 2012 La danse constitue un axe important de la production de Poulenc et un modèle essentiel de son style, axe qu’il convient d’examiner globalement. Les URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1012351ar références explicites (dans les titres) ou implicites aux danses irriguent toute DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/1012351ar son oeuvre, en dehors même des ballets, et contribuent à créer un imaginaire de la danse, lié à ses lectures et à ses souvenirs. Les danses populaires urbaines Aller au sommaire du numéro et les danses anciennes s’inscrivent logiquement dans l’esthétique néoclassique et permettent la constitution d’un « folklore personnel ». Le cas exemplaire des Biches, partition composée pour les Ballets russes de Diaghilev, permet à Poulenc de déployer sa propre poétique fondée sur une relation étroite nouant Éditeur(s) musique, danse et programme intime. Société québécoise de recherche en musique ISSN 1480-1132 (imprimé) 1929-7394 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer cet article Lacombe, H. (2012). Francis Poulenc et la danse. Les Cahiers de la Société québécoise de recherche en musique, 13(1-2), 61–68. https://doi.org/10.7202/1012351ar Tous droits réservés © Société québécoise de recherche en musique, 2012 Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. L’utilisation des services d’Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d’utilisation que vous pouvez consulter en ligne. -

Branding Brussels Musically: Cosmopolitanism and Nationalism in the Interwar Years

BRANDING BRUSSELS MUSICALLY: COSMOPOLITANISM AND NATIONALISM IN THE INTERWAR YEARS Catherine A. Hughes A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music. Chapel Hill 2015 Approved by: Annegret Fauser Mark Evan Bonds Valérie Dufour John L. Nádas Chérie Rivers Ndaliko © 2015 Catherine A. Hughes ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Catherine A. Hughes: Branding Brussels Musically: Cosmopolitanism and Nationalism in the Interwar Years (Under the direction of Annegret Fauser) In Belgium, constructions of musical life in Brussels between the World Wars varied widely: some viewed the city as a major musical center, and others framed the city as a peripheral space to its larger neighbors. Both views, however, based the city’s identity on an intense interest in new foreign music, with works by Belgian composers taking a secondary importance. This modern and cosmopolitan concept of cultural achievement offered an alternative to the more traditional model of national identity as being built solely on creations by native artists sharing local traditions. Such a model eluded a country with competing ethnic groups: the Francophone Walloons in the south and the Flemish in the north. Openness to a wide variety of music became a hallmark of the capital’s cultural identity. As a result, the forces of Belgian cultural identity, patriotism, internationalism, interest in foreign culture, and conflicting views of modern music complicated the construction of Belgian cultural identity through music. By focusing on the work of the four central people in the network of organizers, patrons, and performers that sustained the art music culture in the Belgian capital, this dissertation challenges assumptions about construction of musical culture. -

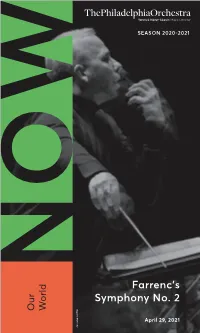

Farrenc's Symphony No. 2 Digital Program

SEASON 2020-2021 Farrenc’s Symphony No. 2 April 29, 2021 Jessica GriffinJessica SEASON 2020-2021 The Philadelphia Orchestra Thursday, April 29, at 8:00 On the Digital Stage Yannick Nézet-Séguin Conductor Paul Jacobs Organ Foumai Concerto grosso, for chamber orchestra First Philadelphia Orchestra performance Poulenc Concerto in G minor for Organ, Strings, and Timpani Andante—Allegro giocoso—Subito andante moderato— Tempo allegro—Molto adagio—Très calme—Lent— Tempo de l’allegro initial—Tempo introduction—Largo Farrenc Symphony No. 2 in D major, Op. 35 I. Andante—Allegro II. Andante III. Scherzo: Vivace IV. Andante—Allegro This program runs approximately 1 hour, 10 minutes, and will be performed without an intermission. This concert is part of the Fred J. Cooper Memorial Organ Experience, supported through a generous grant from the Wyncote Foundation. Philadelphia Orchestra concerts are broadcast on WRTI 90.1 FM on Sunday afternoons at 1 PM, and are repeated on Monday evenings at 7 PM on WRTI HD 2. Visit www.wrti.org to listen live or for more details. Our World Lead support for the Digital Stage is provided by: Claudia and Richard Balderston Elaine W. Camarda and A. Morris Williams, Jr. The CHG Charitable Trust Innisfree Foundation Gretchen and M. Roy Jackson Neal W. Krouse John H. McFadden and Lisa D. Kabnick The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Leslie A. Miller and Richard B. Worley Ralph W. Muller and Beth B. Johnston Neubauer Family Foundation William Penn Foundation Peter and Mari Shaw Dr. and Mrs. Joseph B. Townsend Waterman Trust Constance and Sankey Williams Wyncote Foundation SEASON 2020-2021 The Philadelphia Orchestra Yannick Nézet-Séguin Music Director Walter and Leonore Annenberg Chair Nathalie Stutzmann Principal Guest Conductor Designate Gabriela Lena Frank Composer-in-Residence Erina Yashima Assistant Conductor Lina Gonzalez-Granados Conducting Fellow Frederick R. -

Francis Poulenc Dalai

CSEREKLYEI ANDREA FRANCIS POULENC DALAI DOKTORI ÉRTEKEZÉS 2017 Liszt Ferenc Zeneművészeti Egyetem 28-as számú művészet- és művelődéstörténeti besorolású doktori iskola FRANCIS POULENC DALAI Louise de Vilmorin dalciklusok CSEREKLYEI ANDREA DOKTORI ÉRTEKEZÉS 2017 I Tartalomjegyzék Rövidítések II Köszönetnyilvánítás III Bevezetés IV 1. A dalokról 1 1.1. Hatások 1 1.2. A húszas évek 7 1.3. A harmincas évek eleje 9 1.4. Pierre Bernac 15 1.5. Fordulat 16 1.6. Háborús évek 18 1.7. A háború utáni évek 25 1.8. Az utolsó évtized 29 2. Kompozíciós technikák Poulenc dalaiban 36 2.1. Szövegválasztás, fordítások 36 2.2. Zongorakíséret, hangszerelés 38 2.3. Forma, szerkezet, dallam, harmónia 40 3. Louise de Vilmorin 44 4. Trois poèmes de Louise de Vilmorin (FP 91) 51 5. Fiançailles pour rire (FP 101) 63 6. Métamorphoses (FP 121) 85 7. Záró gondolatok 93 8. Függelék – A dalok jegyzéke 94 9. Bibliográfia 101 II Rövidítések André de Vilmorin André de Vilmorin: Essai sur Louise de Vilmorin. (Paris: Édition Pierre Seghers, 1962.) Audel 1978 Stéphane Audel: My friends and Myself. [Moi et mes amis.] Ford: James Harding. (London: Dennis Dobson, 1978.) Bernac 1977 Pierre Bernac: Francis Poulenc. The Man and His Songs. [Francis Poulenc et ses mélodies]. Ford: Winifred Radford. (London: Victor Gollancz, 1977.) Correspondance 1967 Francis Poulenc: Correspondance 1915-1963. (Paris: Éditions du Seuil, 1967.) Daniel 1982 Keith W. Daniel: Francis Poulenc. His Artistic Development and Musical Style. (Ann Arbor, Michigan: UMI Research Press, 1982.) Gyergyai Gyergyai Albert: „A szép kertésznő”. Kritika 17/4 (1979. ápr.) 19-21. Henri Hell 1958 Henri Hell: Francis Poulenc. -

An Analysis of Tonal Conflict in Stravinsky's

Hieratic Harmonies: An Analysis of Tonal Conflict in Stravinsky’s Mass A thesis submitted by Joseph Michael Annicchiarico In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Music Tufts University May 2016 Adviser: Frank Lehman Abstract Igor Stravinsky’s Mass is the penultimate work of his neoclassical phase, written between the years of 1944 and 1948, just before his landmark piece The Rake’s Progress. The Mass is a highly “conflicted” work, both culturally and musically. As World War II was racing towards its tumultuous end, Stravinsky—oddly, without commission—decided to write a Mass, which is peculiar for someone who converted to the Russian Orthodoxy many years earlier. Musically speaking, the work exhibits conflicts, predominantly in the dialectic between tonality and atonality. Like the war, Stravinsky himself was nearing a turning point—the end of his neoclassical style of composition—and he was already thinking ahead to his opera and beyond. This thesis offers an analysis based on the idea of musical conflict, highlighting the syntactical dialogues between two tonal idioms. My work focuses heavily in particular on the pitch-class set (4–23) [0257], and the role that it plays in both local and global parameters of the work, as well as its interactions with non-functional tonal elements. Each movement will be analyzed as its own unit, but some large-scale relations will be drawn as well. My analysis will bring in previous work from two crucial investigations of the work—by V. Kofi Agawu, and by the composer Juliana Trivers. The Mass has never been a widely discussed work in the oeuvre of such a popular composer, but my hope is that this thesis can help rectify this by bringing overdue analytical attention to crucial elements of Stravinsky’s language in the piece. -

BEYOND the HUMAN VOICE: FRANCIS POULENC's PSYCHOLOGICAL DRAMA LA VOIX HUMAINE (1958) Cynthia C. Beard, B.M. Thesis Prepared Fo

BEYOND THE HUMAN VOICE: FRANCIS POULENC’S PSYCHOLOGICAL DRAMA LA VOIX HUMAINE (1958) Cynthia C. Beard, B.M. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2000 APPROVED: Malena Kuss, Major Professor Deanna Bush, Minor Professor J. Michael Cooper, Committee Member Thomas Sovik, Committee Member William V. May, Dean of the College of Music C. Neal Tate, Dean of the Robert B.Toulouse School of Graduate Studies TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE LIST OF TABLES iii LIST OF MUSICAL EXAMPLES iv Chapter 1. INTRODUCTION 1 2. POULENC, COCTEAU, AND PARIS IN THE 1920s 4 3. FROM THE THEATER TO THE OPERA HOUSE: POULENC’S SETTING OF COCTEAU’S TEXT 13 4. MUSICAL STYLE 26 5. POULENC'S MUSICAL DRAMATURGY FOR LA VOIX HUMAINE 36 6. STRUCTURE OF THE OPERA 42 7. MOTIVIC TREATMENT 54 8. CONCLUSION 75 9. APPENDIX 81 10. BIBLIOGRAPHY 86 ii TABLES FIGURE PAGE 1. Dramatic Phases of La Voix humaine 39 iii MUSICAL EXAMPLES EXAMPLE PAGE 1. 2 mm. before Rehearsal 55, Poulenc’s modification of Cocteau’s text 23 2. 2 mm. before Rehearsal 66, Poulenc’s modification of Cocteau’s text 23 3. Rehearsal 108, Poulenc’s modification of Cocteau’s text 25 4, 2 mm. before Rehearsal 94, Poulenc’s modification of Cocteau’s text 25 5. ,3 mm. Before Rehearsal 53, chromatic wedge 27 6. Rehearsal 100, increased chromaticism 28 7. Beginning, vertical conflict 29 8. 5 mm. after Rehearsal 5, cellular structure 30 9. Rehearsal 60, orchestral support of text delivery 31 10. Rehearsal 14, octatonic 1-2 model and chromatic wedge 33 11.